You are here

In the Twilight Zone: Record Number of U.S. Immigrants Are in Limbo Statuses

Afghan parolees wait in line at Fort McCoy, Wisconsin. (Photo: SPC Froylan Grimaldo/U.S. Army)

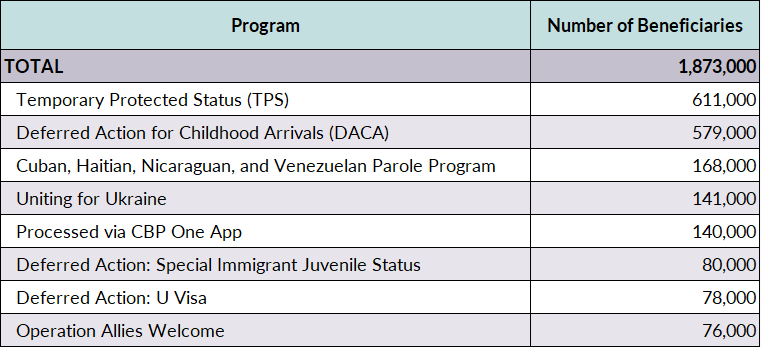

The Biden administration’s embrace of executive authority to grant immigration protections has resulted in a ballooning number of individuals living in the United States with temporary statuses. A record 1.9 million migrants have entered the United States, received authorization to do so, or are present via a twilight immigration status that does not automatically confer any path to permanent residence but temporarily shields recipients from deportation for at least one year, and in many cases offers permission to work legally. Additionally, more than 700,000 other migrants have been allowed to enter the United States through even shorter-term immigration parole to undergo removal proceedings. Whether via humanitarian parole, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), or other programs, the Biden administration has made the grant of liminal status a hallmark of its immigration policy. This is a further sign of the administration’s reliance on executive authority in the absence of congressional action to respond to today’s immigration realities, which include record unauthorized arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border and humanitarian crises.

These twilight statuses allow the government to quickly address what can be fast-developing situations. They also provide welcome relief to migrants who might otherwise be forced to live in or return to countries beset by war, natural disasters, or other crises. But they leave their holders in limbo and, by swelling the numbers of people in impermanent status, ultimately raise policy and integration issues that will not go away if unaddressed.

The population of immigrants in twilight status is notable not only for its size but also for the variety of initiatives involved, including the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and other deferred action programs. The most recent move occurred in July, when the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced that some nationals of Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras who are awaiting processing of their family-based visa applications could enter the United States early on immigration parole. Parole also has been used to manage flows for nationals of certain countries responsible for sizable unauthorized arrivals at the southwest border, permitting some to enter the United States while Mexico accepts the return of an equivalent number. Humanitarian parole has been used to speed the entry of hundreds of thousands of migrants fleeing war in Afghanistan and Ukraine who might otherwise be candidates for refugee resettlement. And the administration has extended TPS, which offers work permits as well as temporary protection from deportation, to hundreds of thousands of immigrants already in the United States, both by renewing pre-existing designations and creating new ones.

It is likely that some of the 1.9 million individuals have switched between temporary statuses or been able to obtain more permanent statuses, such as asylum.

Table 1. U.S. Immigrants with Twilight Statuses, 2023

Notes: Table shows the number of holders of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) as of March 2023. CBP One app numbers are through June 2023. All other numbers indicate the number of people initially granted each type of status or approved for travel. Some grantees may have subsequently obtained a different immigration status, including asylum, TPS, lawful permanent residence, or other forms of legal status.

Sources: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “CBP releases January 2023 Monthly Operational Data” (press release, February 10, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases February 2023 Monthly Operational Data” (press release, March 15, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases March 2023 Operational Data” (press release, April 17, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases April 2023 Monthly Operational Update” (press release, May 17, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases May 2023 Monthly Operational Update” (press release, June 20, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases June 2023 Monthly Update” (press release, July 18, 2021), available online; U.S. Citizenship and Naturalization Services (USCIS), “Count of Active Daca Recipients as of March 31, 2023,” accessed July 19, 2023, available online; Camilo Montoya-Galvez, “U.S. Has Welcomed More than 500,000 Migrants as Part of Historic Expansion of Legal Immigration Under Biden,” CBS News, July 18, 2023. available online; Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2023), available online.

While the practice of using executive authority to allow temporary relief dates back decades—even helping musician John Lennon avoid deportation in the 1970s—current efforts to address multiple policy goals are unprecedented—and have provoked criticism from some Republicans, who are seeking to end the administration’s use of parole.

This article reviews the programs created under the Biden administration and the current number of immigrants covered by immigration parole, deferred action, and TPS. It outlines the challenges presented by these twilight statuses in terms of the lack of pathways to permanent residence and the effect on immigrants’ integration into U.S. society.

Parole Used Like Never Before

The most dramatic change under the Biden administration has been in the use of immigration parole. The Immigration and Nationality Act allows the government to grant parole to immigrants facing urgent humanitarian concerns in their country of origin or for significant U.S. public benefit. It provides lawful U.S. entrance and eligibility for work authorization. The government has granted parole to large numbers of people fleeing conflict or persecution in the past, including to 30,000 Hungarians in the 1950s, 15,000 Chinese in the 1960s, and more than 120,000 Vietnamese in the 1970s.

Congress passed the Refugee Act in 1980 partly in response to those situations, recognizing the growing need for a more routinized process to provide protection to refugees and other displaced people, particularly those fleeing communism. But refugee processing today remains slow, with average wait times of four years for those already in the refugee resettlement pipeline. The Biden administration set a cap of 125,000 refugees for fiscal year (FY) 2023, but only 38,700 had been admitted as of June 30. For people who might otherwise have solid cases to be admitted as refugees and face an urgent need for protection, such as some Afghans and Ukrainians fleeing war, the administration has turned to parole to quickly process their admission.

Separately, facing record unauthorized arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border and the inability to return migrants to countries experiencing crisis or that have poor diplomatic relations with the United States, DHS has used parole to reduce the number of unauthorized crossings and restore order, viewing its usage as an alternative means for migrants who might otherwise cross irregularly. Consequently, the Biden administration’s use of parole has vastly outstripped past administrations’ use of this authority.

Parole Programs for Certain Nationalities

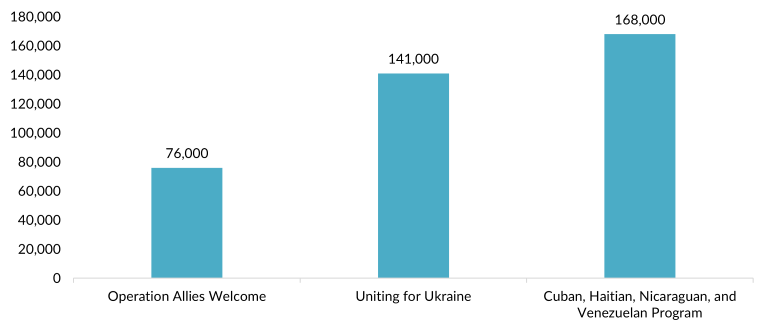

The administration has established new nationality-based parole programs that have resulted in hundreds of thousands of migrants taking flights to enter the United States legally. Among these is a special program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (beginning in October 2022 for Venezuelans and in January 2023 for Cubans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans). Under this program, more than 168,000 people from these countries, which are experiencing severe political or economic turmoil, had been vetted and approved for travel to the United States as of mid-July; approximately 50,000 Haitians, 48,500 Venezuelans, 35,000 Cubans, and 21,500 Nicaraguans had arrived.

Additionally, Operation Allies Welcome (operational from August 2021 to September 2022) evacuated and paroled in 76,200 Afghans after the withdrawal of the U.S. military from Afghanistan and fall of the country to the Taliban. Through Uniting for Ukraine (operational since April 2022), the government had paroled in more than 141,000 Ukrainians as of July 13, welcoming individuals who fled Ukraine after Russia’s invasion in February 2022.

Generally, migrants arriving through these programs receive two years of parole and can apply for work permits, but must seek another route to become lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green-card holders); there is no automatic access to a permanent route.

With expiration dates looming for Afghan and Ukrainian parolees, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is allowing them to temporarily extend their parole, but it is unclear whether such efforts will be repeated. Processes for extensions have not been announced for other nationalities that also will bump up against expiration dates in the months ahead.

Figure 1. U.S. Immigrants Arriving by Nationality-Based Parole Programs Without an Automatic Path to Permanent Status, 2021-23*

* The figure shows data as of September 2022 for those arriving in the United States via Operation Allies Welcome; as of July 13, 2023 for those arriving under Uniting for Ukraine; and as of July 13, 2023 for those approved to travel via the Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan parole programs.

Sources: Camilo Montoya-Galvez, “U.S. Has Welcomed More than 500,000 Migrants as Part of Historic Expansion of Legal Immigration Under Biden,” CBS News, July 18, 2023, available online; U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), “DHS Announces Family Reunification Parole Processes for Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras” (press release, July 7, 2023), available online; DHS, Department of Homeland Security Operation Allies Welcome: Afghan Parolee and Benefits Report (Washington, DC: DHS, 2023), available online.

Apart from the parole programs that have no direct path to permanence, the administration has started new family reunification programs for migrants from Colombia, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, and Honduras who already have filed family-based green-card applications. (The Cuba and Haiti programs were restarted in 2022, and the others in July 2023.) The program will allow an estimated 73,500 people to be considered for parole as of May, letting them enter and remain in the United States while their application is processed. Unlike the other parole programs, which generally allow for two years of status, the family reunification programs grant three years of parole.

Parole Granted at the Border

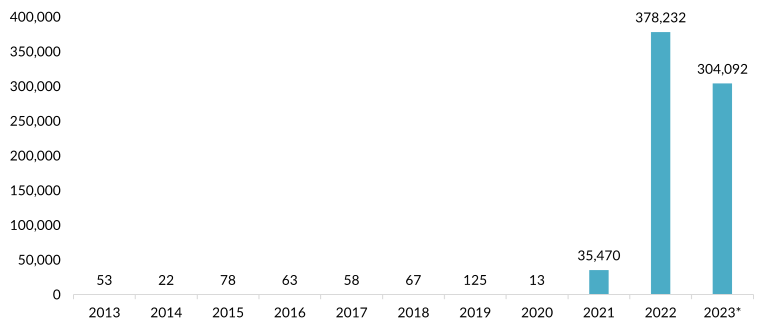

Perhaps the most striking change in the Biden administration’s exercise of parole is its usage by the Border Patrol to allow migrants encountered crossing without authorization to enter for very short periods—60 days in many cases—to expediently process them out of border facilities and place them in removal proceedings. Historically, immigration parole has tended to be used at ports of entry for people with advance permission to enter or who had been screened on an individualized basis for emergencies or exigent circumstances. For those intercepted arriving between ports of entry at the border, from 2008 (the earliest year for which data are available) through 2020, the Border Patrol granted parole to about 770 people. From January 2021, when President Joe Biden took office, to June 2023, border authorities granted parole to about 718,000 individuals encountered between ports of entry.

Figure 2. U.S. Border Patrol Grants of Immigration Parole, FY 2013-23*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 are for the first nine months of the year, October 2022 to June 2023.

Note: Data are for parole granted to migrants crossing the border irregularly between ports of entry.

Sources: Data from 2013 to 2021 are from Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Border Patrol Arrests,” updated July 2022, available online; data from 2022 and 2023 are from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “Custody and Transfer Statistics,” updated July 18, 2023, available online.

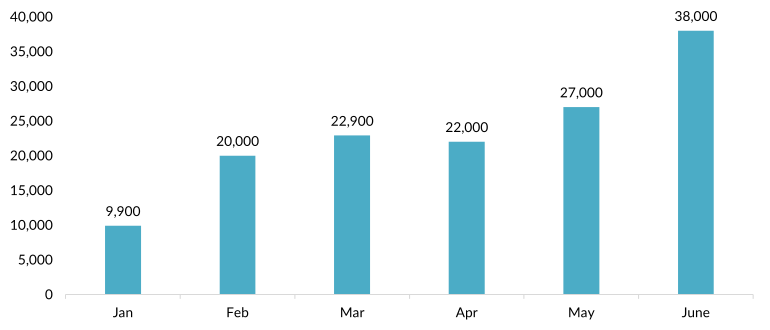

In addition to the significant rise in the use of parole along the southwest border, DHS has dramatically changed how the authority is operationalized. In January 2023, the department began incentivizing migrants to schedule border appointments through the CBP One mobile app. Unlike people encountered between ports of entry, those who receive appointments through the app generally are granted one to two years of parole. Numbers of scheduled appointments have increased; approximately 140,000 migrants had made appointments through June 30, with the largest numbers coming from Haitians, Venezuelans, and Mexicans.

Figure 3. Scheduled CBP One App Appointments by Month, 2023

Note: Data come from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) releases and are approximations. Data for January refer to the period from January 18 to January 31, after the implementation of the CBP One App process. Before May 11, data refer to Title 42 exceptions; after May 11, data refer to appointments to present at a port of entry to be processed.

Sources: CBP, “CBP releases January 2023 Monthly Operational Data” (press release, February 10, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases February 2023 Monthly Operational Data” (press release, March 15, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases March 2023 Operational Data” (press release, April 17, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases April 2023 Monthly Operational Update” (press release, May 17, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases May 2023 Monthly Operational Update” (press release, June 20, 2023), available online; CBP, “CBP Releases June 2023 Monthly Update” (press release, July 18, 2021), available online.

Deferred Action for Unauthorized Immigrants Already in the United States

The Biden administration has also strengthened, and in some cases significantly expanded, various forms of relief that prevent deportation and establish eligibility for work authorization for some unauthorized immigrants already in the United States. For example, a regulation issued in 2022 was intended to fortify the DACA program against possible legal challenges. First announced in 2012, DACA has been the subject of litigation resulting in court orders blocking new applications. Approximately 800,000 people have benefitted from the program over its lifetime, and 579,000 were registered as of March 2023. Anticipating a court decision that may terminate the DACA program as soon as August, the administration has stated that it is considering other ways to protect beneficiaries; details are not public.

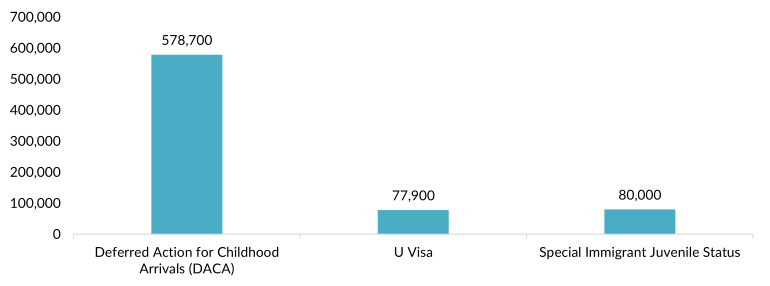

Other Grants of Deferred Action

Beyond DACA, the government has extended deferred action to tens of thousands of unauthorized immigrants, protecting them from removal and allowing them to apply for work authorization. Among these are nearly 78,000 witnesses or victims of crimes with a U visa application that the government has recognized as bona fide; their grant of deferred action lasts four years. Another approximately 80,000 abused, abandoned, or neglected youth deemed Special Immigrant Juveniles who are waiting to be able to apply for green cards have also received deferred action for four-year grants in a process that began in 2022. Both programs ameliorate the impact of waits caused by visa backlogs, which can prevent immigrants who have been found eligible for protection from obtaining a green card for years. A more recent program was launched in January to defer deportation for unauthorized immigrants in labor disputes with their employers, formalizing what had previously been an ad hoc process. At least 450 immigrants had requested deferred action through this program through July.

Figure 4. Immigrants with a Grant of Deferred Action, 2023

Note: Some immigrants granted deferred action may have subsequently received green cards.

Sources: USCIS, “Count of Active Daca Recipients as of March 31, 2023,” accessed July 19, 2023, available online; USCIS, “Number of Form 1-918, Petition for U Nonimmigrant Status Bona Fide Determination,” accessed July 19, 2023, available online; Panel discussion at the spring conference of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, Washington, DC, April 27-28, 2023.

Several other smaller programs have also provided temporary protections for certain groups, including the Central American Minors program, parole for veterans who were previously deported, and an initiative to reunite separated families. Noncitizens can also request that DHS grant them parole or deferred action on an individual basis.

Temporary Protected Status

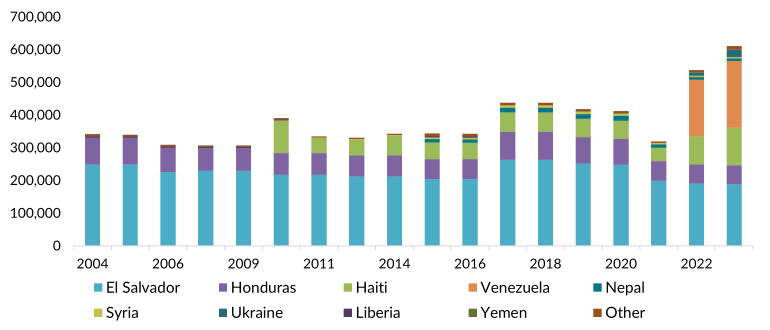

A record number of noncitizens in the United States are covered by TPS, which provides relief from deportation for up to 18 months at a time and eligibility to apply for work authorization. TPS can be offered to nationals of countries facing conditions that prevent their return, including natural disaster or war. TPS was first granted in 1990 to certain Salvadorans residing in the United States, and subsequent administrations—Democrat and Republican alike—have granted and extended TPS designations for nationals of 28 countries. The result has been that, for some, the ostensibly temporary status has lasted more than 30 years. Approximately 611,000 immigrants held TPS as of March 2023.

Figure 5. Temporary Protected Status Recipients, by Nationality, 2004-23

Notes: Figure is based on data from the Congressional Research Service (CRS). Some of the changes by year may be due to differences in how CRS counts the number of people with TPS from various countries. A change in methodology between 2016 and 2017 generated an increase in estimates; another change between 2020 and 2021 generated a decrease. Prior to 2021, CRS estimates included lawful permanent residents (LPRs) as TPS holders, but subsequent estimates have excluded them. Data for 2007 and 2013 were unavailable.

Sources: Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2005), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2006), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2006), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2008), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2010), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2010), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2011), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2012), available online; Ruth Ellen Wasem and Karma Ester, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2014), available online; Lisa Seghetti, Karma Ester, and Ruth Ellen Wasem, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2015), available online; Name redacted, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2016), available online; Name redacted, Temporary Protected Status: Overview and Current Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2017), available online; Name redacted, Temporary Protected Status: Overview and Current Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2018), available online; Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status: Overview and Current Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2019), available online; Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status: Overview and Current Issues (Washington, DC: CRS, 2020), available online; Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: CRS, 2021), available online; Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: CRS, 2022), available online; Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: CRS, 2023), available online.

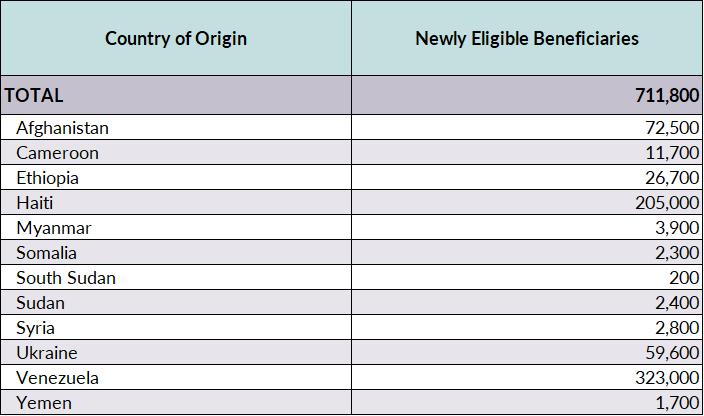

Under the Biden administration, new TPS designations have been issued for six countries (Afghanistan, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Myanmar [also known as Burma], Ukraine, and Venezuela), and extended for ten others (El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen). The government has also granted or extended a similar protection, deferred enforced departure (DED), for people from Hong Kong and Liberia, with an estimated 3,900 and 2,800 covered respectively.

Table 2. U.S. Immigrants Newly Eligible for Temporary Protected Status, 2021-23

Sources: Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: CRS, 2023), available online; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Designation of Venezuela for Temporary Protected Status and Implementation of Employment Authorization for Venezuelans Covered by Deferred Enforced Departure,” Federal Register 86, no. 44 (March 9, 2021): 13574, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Somalia for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 88, no. 48 (March 13, 2023): 15434, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Burma (Myanmar) for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 186 (September 27, 2022): 58515, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Sudan for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 75 (April 19, 2022): 41863, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Ukraine for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 75 (April 19, 2022): 23211, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of South Sudan for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 42 (March 3, 2022): 41863, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Afghanistan for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 98 (May 20, 2022): 30976, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Cameroon for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 109 (June 7, 2022): 34706, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Syria for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 146 (August 1, 2022): 46982, available online; USCIS, “Reconsideration and Rescission of Termination of the Designation of Nepal for Temporary Protected Status; Extension of the Temporary Protected Status Designation for Nepal,” Federal Register 88, no. 118 (June 21, 2023): 40317, available online; USCIS, “Designation of Ethiopia for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 87, no. 237 (December 12, 2022): 76074, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Yemen for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 88, no. 1 (January 3, 2023): 94, available online; USCIS, “Reconsideration and Rescission of Termination of the Designation of El Salvador for Temporary Protected Status; Extension of the Temporary Protected Status Designation for El Salvador,” Federal Register 88, no. 118 (June 21, 2023): 40282, available online; USCIS, “Reconsideration and Rescission of Termination of the Designation of Honduras for Temporary Protected Status; Extension of the Temporary Protected Status Designation for Honduras,” Federal Register 88, No. 118 (June 21, 2023): 40304, available online; USCIS, “Reconsideration and Rescission of Termination of the Designation of Nicaragua for Temporary Protected Status; Extension of the Temporary Protected Status Designation for Nicaragua,” Federal Register 88, No. 118 (June 21, 2023): 40294, available online; USCIS, “Extension and Redesignation of Haiti for Temporary Protected Status,” Federal Register 88, No. 17 (January 26, 2023): 5022, available online.

Limbo Comes with a Cost

Taken together, these programs and designations represent a fundamental shift in the profile of immigrants in the United States, with more people than ever before holding twilight statuses that enable them to lawfully work and live in the United States, if only for short periods of time and without certainty of extension. In a departure from past practice, the Biden administration has deployed these efforts not only for humanitarian reasons, but also to bring order to the U.S.-Mexico border by using parole to channel migrants through the system.

Still, demand continues to outstrip availability, and the question remains whether these programs incentivize more migrants to head towards the United States. As of May, USCIS had received more than 1.5 million applications for the Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela parole program, which can allocate 30,000 approvals per month. Also since May, USCIS has shifted away from its initial first-in, first-out system for all cases, with half selected via a random lottery.

Some observers have expressed concern that the programs, which are not designed to screen for individual vulnerability, do not target migrants most in need of protection. Rather, some programs’ requirements that migrants have a U.S. sponsor, pay to fly to the United States, and have valid passports limit access to those with resources and connections.

Nevertheless, the Biden administration’s use of liminal status stands in stark contrast to the Trump administration’s attempts to roll back many temporary protection programs and legal immigration more broadly. Some Republican-led states and former Trump administration officials have challenged several of these Biden initiatives in court, particularly the expanded use of parole. A lawsuit against the Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela program currently before a federal court in Texas may result in the program being blocked. This would not only affect parolees but could also impact Mexico’s cooperation on a range of border issues, which it has conditioned on the entrance of nationals of those four countries into the United States.

Different Programs, Same Uneasy Status for Most

The fate of those with twilight statuses is precarious. A future administration could rescind these temporary protections, as President Donald Trump repeatedly attempted to do during his tenure. And litigation could bring a halt to any of these programs, leaving beneficiaries without legal status.

In the past, Congress passed adjustment acts for parolees and recipients of TPS and DED, such as for Hungarians, Cubans, and Vietnamese. Based on the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act, new Cuban parolees can apply for a green card after one year. But there is no imminent action to provide permanent status to most of today’s liminal status holders, due to lack of bipartisan consensus on immigration. The only exception to this is the family reunification parole programs, beneficiaries of which can seek permanent residence under existing law. Recently, Rep. Bill Keating (D-MA) introduced the Ukrainian Adjustment Act, but similar bills for Afghans and Venezuelans have failed to gain traction, as have those for recipients of DACA, DED, and TPS.

And individuals potentially eligible for some more enduring status may have difficulty applying, in part because they may not be aware of their eligibility, something that is often linked to lack of access to legal representation.

Lacking other avenues to apply for a more permanent status, many twilight status recipients have sought asylum, which if granted provides a pathway to a green card after one year. More than 263,000 asylum applications were filed at USCIS in the first eight months of FY 2023, a record high, with Cubans, Venezuelans, Colombians, Nicaraguans, and Haitians the top nationalities. These applications and the many others filed for deferred action, TPS, and related work permits have overloaded already backlogged processes at USCIS. Wait times for approval of TPS for Haitians now clock in at 17.5 months on average, almost the 18-month duration of the status itself. Stakeholders have encouraged the agency to introduce efficiencies such as transferring an individual’s biometrics from one application to another, instead of repeating the process multiple times.

Without a path forward, many twilight status holders unable to secure long-term residence will be forced to return to their origin countries, despite conflict, economic crisis, or other turmoil there. Many others will simply remain in the United States without legal status, adding to the population of approximately 11 million unauthorized immigrants.

This absence of certainty raises concerns for immigrants themselves, their families, U.S. communities, and a broad range of institutions. Employers, schools, and government offices across the country are impacted by immigrants’ right to work and access benefits. Likewise, migrants uncertain about their future must make difficult choices about housing, education, health care, and their careers, all of which affect their fuller integration into U.S. society.

The authors thank Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh, Jiaxin Wei, and Julia Gelatt for research assistance.

Sources

Bruno, Andorra. 2020. Immigration Parole. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Gelatt, Julia and Doris Meissner. 2022. Straight Path to Legal Permanent Residence for Afghan Evacuees Would Build on Strong U.S. Precedent. Migration Policy Institute (MPI) commentary, March 2022. Available online.

Harrington, Ben. 2018. An Overview of Discretionary Reprieves from Removal: Deferred Action, DACA, TPS, and Others. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Montoya-Galvez, Camilo. 2023. U.S. Has Welcomed More than 500,000 Migrants as Part of Historic Expansion of Legal Immigration Under Biden. CBS News, July 18, 2023. Available online.

Office of U.S. Representative Mike Quigley. 2023. Quigley, Keating, Fitzpatrick, and Kaptur Introduce Ukrainian Adjustment Act. Press release, June 8, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2023. Asylum Quarterly Engagement Script & Talking Points. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2023. Check Case Processing Times. Accessed July 26, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Count of Active DACA Recipients by Month of Current DACA Expiration as of March 31, 2023. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2023. LRIF and DED Liberia Engagement – Q&A. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2023. Number of Form I-918 Petitions for U Nonimmigrant Status by Fiscal Year, Quarter, and Case Status. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2023. Petition for U Nonimmigrant Status Bona Fide Determination Review as of March 31, 2023. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2023. Department of Homeland Security Operation Allies Welcome Afghan Parolee and Benefits Report: Fiscal Year 2022 Report to Congress. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

---. 2023. DHS Announces Process Enhancements for Supporting Labor Enforcement Investigations. Press release, January 12, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Fact Sheet: Data from First Six Months of Parole Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans Shows that Lawful Pathways Work. July 25, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Fact Sheet: U.S. Has Expanded Labor Visa Opportunities. July 31, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman (CIS Ombudsman). 2023. Annual Report 2023. Washington, DC: CIS Ombudsman. Available online.

U.S. State Department, Refugee Processing Center. 2023. Refugee Admissions Report as of June 30, 2023. Updated June 30, 2023. Available online.

Wilson, Jill H. 2023. Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.