You are here

U.S. Border Asylum Policy Enters New Territory Post-Title 42

Migrant possessions at an irregular crossing point between Piedras Negras, Coahuila, and Eagle Pass, Texas. (Photo: Ariel G. Ruiz Soto)

U.S. border enforcement finds itself in an uncertain new era now that the pandemic-era Title 42 border expulsions policy has been lifted. The chaos predicted to occur in the days after the May 11 end of the public-health emergency declaration did not immediately materialize. The unexpected dip in arrivals could be seen as a sign of a new normal, but may also be a temporary pause before a renewed uptick. Strong migration push factors through much of the Western Hemisphere and beyond may mean that there is continued pressure on the U.S.-Mexico border in the months ahead.

In response to the end of a Title 42 order that resulted in more than 2.8 million expulsions at the U.S.-Mexico border, the Biden administration has issued a slew of fresh policies to bolster a border enforcement regime developed in the 1990s—mostly to halt unauthorized economic migrants from Mexico. Today, that regime is tasked with managing an historic level of asylum seekers and other arrivals from an increasing number of countries across the planet. The administration is hoping to funnel migrants in orderly fashion through official ports of entry, yet the government's finite processing capacity means many are receiving only initial screenings and then are being allowing into the United States to appear at immigration proceedings, frequently many years in the future. Meanwhile, migrants who cross without authorization between ports of entry now face new hurdles that in some ways are more consequential than those of Title 42, which prevented access to asylum.

To accomplish its goals, the government is racing to scale up its capacity for processing new arrivals by surging resources to the border at the expense of immigration adjudications elsewhere. The new process also depends on cooperation from other countries—particularly Mexico— to accept returned migrants, including those from places such as Cuba and Venezuela where U.S. diplomatic relations are strained. Looming over the changes is the specter of ongoing litigation, which could dramatically upset the new process. And finally, political pressures are likely to put the administration in a delicate position, with significant criticism coming from within President Joe Biden's own party. This article analyzes the new immigration landscape and ramifications nationwide.

A Return to Title 8: Expedited Removal and Processing Asylum Claims

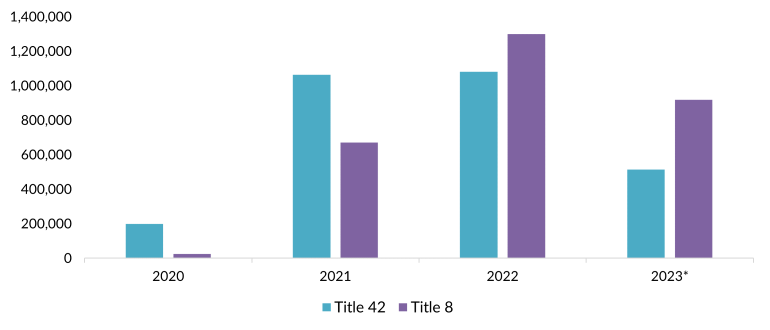

Title 42, which was imposed in March 2020, marked an unprecedented chapter in U.S. immigration history. Never before had an emergency health measure been invoked to summarily expel asylum seekers and other migrants arriving at the border without authorization. Ending the COVID-19-related emergency declaration that triggered the use of Title 42 meant a return to the normal immigration authority, Title 8 of the U.S. code. While this marked a formal shift for arrivals at the border, it simply sped up a transition that was already well underway. In April, just before Title 42 was lifted, 65 percent of unauthorized arrivals were processed under Title 8, with much higher percentages for nationalities from countries other than Mexico and northern Central America.

Figure 1. Number of Southwest Border Encounters, by Legal Authority Used, FY 2020-23*

* Data for 2023 are for the first seven months of the fiscal year.

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of data from U.S. Border Patrol, “Nationwide Encounters,” updated May 17, 2023, available online.

Title 8 is legally more punitive than Title 42. Under Title 8, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) places noncitizens arriving without authorization into expedited removal, without a hearing. Those who are deported under expedited removal are barred from re-entering the country for five years and face criminal charges if they attempt another unlawful re-entry. On the other hand, people expelled under Title 42 faced no such sanctions, leading unsuccessful crossers to repeat their attempts.

During the expedited removal process, people who claim fear of persecution in their country of origin are entitled to a credible fear interview to determine their preliminary eligibility for asylum. If they pass this first step, they are released into the interior of the country to pursue their asylum case. Those who do not seek asylum protection or who do not pass the credible fear interview may be removed. Most asylum seekers pass this initial step: From February 2022 through January, asylum officers denied 32 percent of credible fear cases, but some of those decisions were later overturned by immigration judges, leaving a total denial rate of 23 percent of cases, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC).

Resource capacity plays a major role in this processing. Expedited removal, despite what its name suggests, takes time. Credible fear determinations take longer. At times of significant border arrivals, DHS cannot place everyone into expedited removal or subject them to credible fear determinations. As a result, some noncitizens may be released into the U.S. interior with a charging document known as a notice to appear (NTA) in immigration court, which schedules them for deportation proceedings. This court process can take years; for example, some recent arrivals in New York City have been scheduled for hearings in 2027. In some cases, noncitizens may be allowed in and issued a notice to report to a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) office. DHS officials may also allow noncitizens to enter the country temporarily via humanitarian parole, which allows them to remain in the country for a designated period and obtain work authorization.

All such noncitizens still face removal proceedings and can be deported unless they have a basis to seek lawful status, including asylum. To seek asylum, noncitizens who have met the credible fear test are ordered to appear in immigration court, or are ordered to report to an ICE office where they can defensively seek asylum in removal proceedings. Parolees, on the other hand, can affirmatively seek asylum at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). In either route, migrants with successful claims are granted the same legal status.

Biden Administration Ushers in a New Border Asylum Policy

In anticipation of the end of Title 42, the administration announced in early January a new rule to usher in a radically different asylum system at the U.S. southwest border. The new rule, formally issued on May 10, declared that noncitizens (not including unaccompanied minors) who cross the border without permission will be presumed ineligible for asylum unless they applied for and were denied asylum in a transit country. They only have access to lesser forms of relief—withholding of removal or protections under the Convention Against Torture—regardless of whether they go through expedited removal at the border or are released into the country. Migrants who show they face a medical emergency, imminent threat to life, or are a victim of trafficking may be allowed to pursue their asylum claim.

An individual migrant could thus be screened under the new rule multiple times. Those who invoke asylum protection while in expedited removal will be screened by an asylum officer for exemptions to the presumption of ineligibility for asylum and credible fear at the same time. Also, those let into the country without a credible fear determination and those admitted after passing the credible fear screening will have their eligibility for exceptions determined during their full asylum adjudication, either by an asylum officer or an immigration judge.

The new border asylum rule incentivizes asylum seekers to schedule an appointment with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) using the CBP One app. The transit rule does not apply to those with appointments, although space is limited; as of this writing, about 1,000 appointments per day were available. For comparison, authorities encountered unauthorized migrants an average of more than 7,000 times daily in April.

Capacity Constraints at the Border

DHS’s ability to implement the new asylum rule runs into longstanding capacity constraints. Ports of entry are run by CBP's Office of Field Operations (OFO), which lacks the physical space and personnel to process all migrant arrivals. Thus, only a fraction of those with CBP One appointments undergo actual asylum screening. Instead, they are often screened only for security concerns and quickly released into the country with two years of parole and an NTA. Hence, although the administration is encouraging asylum seekers to arrive at ports of entry, only minimal processing happens there.

Even noncitizens who arrive without an appointment may be issued parole and an NTA. But depending on capacity, they could also be transferred to the custody of the Border Patrol (also a branch of CBP) or ICE—for those deemed threats to national security or public safety—and placed into expedited removal.

For noncitizens encountered between ports of entry, Border Patrol officials place as many as possible into expedited removal, during which they are held in ICE detention. The agency has recently begun conducting credible fear determinations for some noncitizens without putting them into detention—a faster process that was initiated during the Trump administration. When the practice was in place previously, just 23 percent of migrants met the credible fear finding.

Border Patrol and ICE face similar space constraints as OFO. At the peak of the rush before Title 42 ended, Border Patrol held about 29,000 people at its soft-sided tent facilities, well above the capacity range of 18,000 to 20,000. ICE’s detention capacity, driven by COVID-19-related restrictions, was until recently limited to a daily average population of about 24,000; the end of those requirements means the agency can now hold thousands more, including detainees from its interior enforcement.

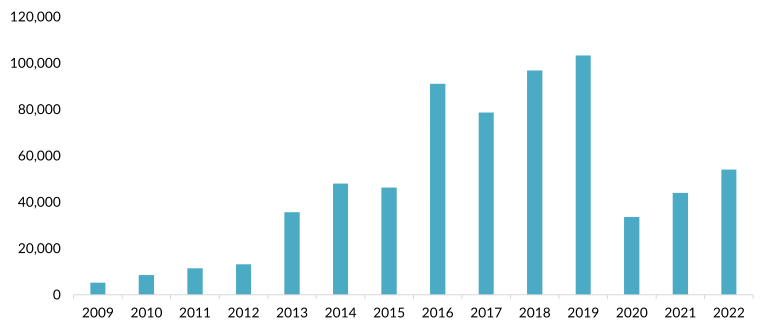

The number of asylum officers available to conduct credible fear interviews for those seeking asylum while in custody is also limited. DHS plans by the end of May to conduct 1,000 interviews per day using 1,100 asylum officers. That would be a record. Historically, the most credible fear interviews DHS has ever conducted was 103,000 in fiscal year (FY) 2019—an average of 283 per day. In the first three months of FY 2023, USCIS completed 21,200 credible fear screenings, a rate of about 230 per day.

Figure 2. Credible Fear Cases Completed, FY 2009-22

Sources: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Credible Fear Cases Completed and Referrals for Credible Fear Interview," December 12, 2022, available online; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Credible Fear Screening, By Outcomes, Office, Month,” accessed May 24, 2023, available online.

Thus, the resource constraints are real. In the four days leading up to the end of Title 42, Border Patrol encountered about 10,000 migrants per day. On May 10 and 11, DHS released almost 9,000 migrants into the country with just parole documents because it was unable to issue them NTAs. In the week after Title 42 was lifted, the number of daily encounters dropped to an average of about 4,100.

Still, administration officials have cautioned that this decline may be temporary, as migrants and smugglers assess the impacts of the new plans and attempt to secure CBP One appointments. In fact, an estimated 60,000 migrants were waiting near the U.S.-Mexico border as Title 42 ended, according to Border Patrol Chief Raul Ortiz. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees has also warned that 400,000 migrants this year could travel through the dangerous Darien Gap between Colombia and Panama on their way to the U.S. border, after a record 248,000 crossed last year. While it remains to be seen how many people will arrive at the border without authorization in the coming weeks and months, it is clear that DHS’s capacity limitations mean thousands will be released into the country rather than removed, even under the restrictive new asylum transit rule.

The government’s ability to physically remove noncitizens has its own constraints, determined both by its resources and other countries’ cooperation. DHS lacks the necessary planes and pilots to return all removable noncitizens. Furthermore, Mexico has stated it will accept only up to 1,000 foreign nationals per day. While the administration has pushed other countries to accept returns of their nationals, Colombia recently halted return flights temporarily due to allegations of “degrading treatment” for returnees. In the first week after Title 42 was lifted, DHS returned more than 11,000 migrants to more than 30 countries.

Court Intervention Could Derail Plans

In addition to resource limitations, court challenges have imperiled the administration’s post-Title 42 border strategy. A day before the policy change, Florida sued DHS over its use of parole, and a federal judge quickly barred the government from releasing into the country noncitizens in custody, raising fears of dangerous overcrowding in already overcapacity facilities. Separately, Republican-led states sued to block a new program granting parole to some Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans who fly into the United States, which Mexico has made clear is a condition of its willingness to accept deported foreign nationals. A judge could end the program as early as July; if that happens, it is not clear how Mexico will respond.

Meanwhile, immigrant advocates have decried elements of the new border policy that they contend mark a return to the era of President Donald Trump, especially the restrictions on access to asylum and screenings in custody without legal counsel. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other groups challenged Biden’s asylum transit rule by reviving a Trump-era lawsuit that had been put on pause. On May 23, Texas brought its own challenge to the new border rule, saying that the CBP One app encourages unauthorized immigration. If the regulation is found to be unlawful, the pressure of border arrivals will likely increase.

Effects of the Administration’s Focus on the Border

The Biden administration has adopted a whole-of-government approach to address border arrivals, which will have long-lasting effects on other U.S. immigration system functions. The decision to shift personnel to deal with border arrivals means that other administrative processes have slowed down. For instance, as a direct result of redirecting asylum officers and other staff, USCIS cancelled many previously scheduled asylum proceedings in May—affecting congressionally mandated timelines to process Afghan applicants. It is not clear when these interviews will resume, and the backlog of asylum applications will meanwhile continue to grow. As of December, a record 667,000 affirmative asylum cases were pending at USCIS. New filings suggest FY 2023 will set another record.

Similarly, a corps of immigration judges was redirected to work seven days a week and review credible fear interviews virtually. Consequently, long-pending deportation proceedings will take even longer. Before the end of Title 42 and the reallocation of judges, asylum cases took approximately four years. As of January, the courts’ overall backlog stood at a record 2.1 million cases, 865,000 of which were asylum cases, a number that is likely to grow.

The highly publicized increase in arrivals has had profound political impacts across the country, which may become more pronounced if numbers rise anew. Many officials in interior cities are increasingly feeling pressure and calling on the federal government for support, financial and otherwise. Chicago and Denver are among the jurisdictions that have declared emergencies related to migrant influxes in recent months. Facing crises in their shelter systems, Democratic mayors such as New York City’s Eric Adams and Washington, DC’s Muriel Bowser recently restricted migrants’ access to government housing. Throughout the country, growing consensus around immigrants’ need to lawfully work and support themselves while they await asylum processing has also led to increased calls for policy changes regarding work authorization, which currently is not available until 180 days after filing an asylum application.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a 2024 Republican presidential candidate, recently denounced “Biden’s border crisis” as he promoted a new state law with sweeping restrictions targeting unauthorized immigrants. All other Republican presidential candidates have similarly used border challenges as centerpieces of their early campaigns.

Given these challenges, calls for Congress to act have increased, including from city and state officials. In early May, the House passed Republican legislation to increase border enforcement and limit access to asylum, which is unlikely to be considered in the Senate and which Biden has threatened to veto, but which some conservatives have sought to tie to ongoing debt ceiling negotiations. A bill recently introduced by Representatives María Elvira Salazar (R-FL) and Veronica Escobar (D-TX)—the broadest bipartisan immigration legislation in a decade—would advance a number of measures to bolster resources, improve border technology, and establish multiagency border processing centers.

In the Senate, a group including Kyrsten Sinema (I-AZ), Thom Tillis (R-NC), and Joe Manchin (D-WV) is aiming to secure support for a proposal that would revive Title 42-like expulsion powers for two years. Similar attempts have garnered support from some moderate Democrats, and the 2024 elections may exert powerful pressures for lawmakers to define themselves on the issue. If Congress acts, sufficient resources would be needed to translate legislation into action, and in particular for aspects beyond the border enforcement spending that seems a rare area of consensus for both political parties on immigration.

As the new reality unfolds, the world is watching. The European Union faces its own challenges with high arrivals and backlogged systems and has at times considered whether migrants might be made to submit asylum applications en route, before they reach its shores. Other countries such as Canada are conducting reviews of their immigration systems, and are looking to the United States for workable policies to replicate. Perhaps mostly importantly, migrants around the world, their family members in the United States, and smuggling networks are also watching to see whether the new policies will make it easier or harder to enter the United States.

The authors thank Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh and Ashley Podplesky for research assistance.

Sources

Cartwright, Thomas H. 2023. ICE Air Flights April 2023 and Last 12 Months. Witness at the Border, May 9, 2023. Available Online.

East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Biden. 2023. 4:18-cv-06810. Northern District of California. May 18, 2023. Available online.

Florida v. Mayorkas. 2023. Joint Notice of Compliance with ECF No. 18. May 15, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. No. 3:23-cv-9962-TWK-ZCB. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida, Defendants' Further Response to Order to Show Cause. May 19, 2023. Available online.

Huddleston, Kate. 2021. Ending PACR/HARP: An Urgent Step toward Restoring Humane Asylum Policy. Just Security, February 16, 2021. Available online.

Migración Colombia. 2023. Cancelación de vuelos y tratos degradantes motivan la suspensión temporal de llegada de retornados: Migración Colombia. Press release, May 4, 2023. Available online.

Montoya-Galvez, Camilo. 2023. Migrant Border Crossings Drop from 10,000 to 4,400 per Day after End of Title 42. CBS News, May 17, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. U.S. Deported More than 11,000 Migrants in the Weeks after Title 42 Ended. CBS News, May 19, 2023. Available online.

Ortiz, Raul L. 2023. Memorandum from the Chief of U.S. Border Patrol to all Chief Patrol Agents and All Directorate Chiefs, Policy on Parole with Conditions in Limited Circumstances Prior to the Issuance of a Charging Document (Parole with Conditions). May 10, 2023. Available online.

Servicio Nacional de Fronteras (SENAFRONT). N.d. Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: Año 2022: Accessed May 19, 2023. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2023. Immigration Court Asylum Backlog. Updated April 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Immigration Court Backlog Tool. Updated January 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Immigration Judges Overturn Asylum Officer's Negative Credible Fear Findings in a Quarter of All Cases. March 14, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2023. Fact Sheet: Circumvention of Lawful Pathways Final Rule. May 11, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Letter to Honorable Andy Barr, U.S. House of Representatives. February 17, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2023. Fact Sheet: Update on DHS Planning for Southwest Border Security Measures as the Title 42 Public Health Order Ends. May 1, 2023. Available online.

Valencia, Iván. 2023. Migrants Crossing Dense Darien Jungle at Colombia-Panama Border Find Increasingly Organized Route. Associated Press, May 11, 2023. Available online.