You are here

Mounting Backlogs Undermine U.S. Immigration System and Impede Biden Policy Changes

A pile of documents on a desk. (Photo: iStock.com/notwaew)

The Biden administration is seeking to overhaul the U.S. immigration system, expanding protections to hundreds of thousands of immigrants and embarking on a plan to restructure the asylum process at the U.S.-Mexico border. But ever-swelling backlogs in immigration applications and court hearings have slowed legal immigration, threatened to undermine the integrity of the system as a whole, and could jeopardize the success of the Biden immigration agenda.

Much of the backlogs in processing immigration applications is a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced a months-long stall to many government services in 2020 and created slowdowns even upon the reopening of offices at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the State Department, which respectively process applications for immigration benefits from individuals in the United States and abroad. But at USCIS and in the immigration courts where removal proceedings are decided, the pandemic only exacerbated sizeable bottlenecks that had existed for years.

The immigration court backlog now tops 1.6 million cases, up from 1.1 million before the pandemic and more than double the caseload that existed in fiscal year (FY) 2018. At USCIS, the backlog has surged from 5.7 million applications at the end of FY 2019 to about 9.5 million as of February. And at the State Department, waits for in-person consular interviews for immigrant visas rose to a high of 532,000 last July, up from an average 60,900 in 2019 before the pandemic.

Case backlogs can trap individuals in limbo for months or years, with enormous implications for themselves, their families, employers, and the U.S. immigration system writ large, which suffers when it lacks transparency and predictability. Would-be migrants abroad waiting for State Department interviews may remain separated from U.S.-based family members, lose out on job offers, or miss chances to enroll in educational institutions. Given the delays in approving work authorization documents, many immigrants living in the United States have been locked out of or forced to leave their jobs even as the country is facing a high demand for workers. And long waits for immigration court hearings delay protections for vulnerable populations while creating a magnet for those who may not be eligible for asylum yet apply for protection knowing resolution of their case may be years off. The average immigration case completed in January 2022 had been pending for about two and a half years, with some courts seeing average waits in excess of three years.

Beyond harming the effectiveness of the immigration system, the backlogs have the potential to dull the impact of the Biden administration’s immigration ambitions. Since taking office last year, the administration has expanded Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to certain nationals of Myanmar and Venezuela already in the United States, and extended existing protections for U.S. residents from Haiti, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen, providing work authorization and relief from deportation for an estimated 427,000 additional people. Recipients’ protections and work authorization can only be granted for up to 18 months at a time, meaning efficient processing is crucial.

The government has sought to make it easier for individuals with advanced degrees in STEM fields to access temporary visas and employment-based green cards. The administration is offering relief from deportation for certain applicants for U visas, which are available to victims of serious crimes who assist law enforcement, and plans to do so for unauthorized immigrant workers who report workplace violations to the government. It also has rescinded travel bans on nationals from 13 countries, allowing people previously denied visas to reapply. All of these efforts will remain theoretical if authorities are unable to efficiently process applications for beneficiaries of these changes. Likewise with the proposal (first advanced by the Migration Policy Institute) to create greater efficiency and fairness in processing asylum cases at the U.S.-Mexico border by shifting asylum cases from the overburdened immigration courts to the USCIS Asylum Division.

Although President Joe Biden was by no means the architect of the lengthy queues in which many migrants and would-be immigrants have found themselves, failure to resolve both the impacts of the pandemic and broader structural challenges will leave some of his administration’s immigration promises unrealized.

The Pandemic Swells Pre-Existing Backlogs

Processing backlogs have long been rampant across the immigration system, even well before the pandemic.

Processing Delays at USCIS

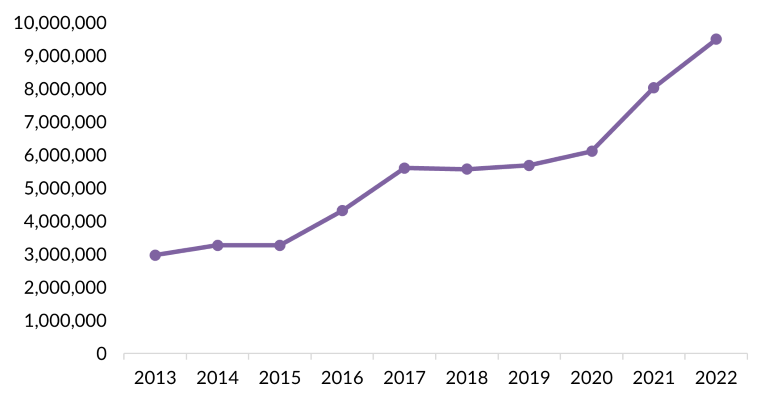

At the end of FY 2013, USCIS had 3 million pending applications; the number increased to 5.7 million by the end of FY 2019, 6.1 million in September 2020, 8 million in September 2021, and about 9.5 million as of February 2022 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of Pending Immigration Applications at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2013-22

Note: Figures for fiscal year (FY) 2013 through FY 2021 show the number of pending applications of all types at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) as of the end of the fiscal year. FY 2022 data reflect the number of pending applications as of February 2022.

Sources: Data for FY 2013 through FY 2021 are from the authors’ analysis of USCIS, “All USCIS Application and Petition Form Types,” multiple years, available online; data for FY 2022 are from USCIS, USCIS Progress on Executive Orders, Virtual briefing, February 2, 2022, available online

Funding constraints and policy changes were responsible for part of the pre-pandemic increase in caseload at USCIS. Since 1988, Congress has mandated that the costs of adjudicating immigration applications be funded by applicants’ fees. However, certain applicants, including those seeking refugee status and asylum, are exempt from paying USCIS application fees. Meanwhile, the Obama administration tasked the agency with setting up the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which like all new programs demanded additional expenses. These costs came out of fees paid by other applicants and grew larger as the numbers of individuals seeking asylum grew. USCIS has not raised its fees since 2016 (a 2020 attempt was blocked by the courts), thus limiting the agency’s ability to increase staffing. Upon entering office, the Trump administration made immigration application forms longer, required more green-card applicants to sit for in-person interviews, asked more applicants for additional evidence, and required more scrutiny of renewal applications. All of these changes, which were widely seen as attempts to lower immigration levels, increased the resources that staff spent on each application.

The situation worsened during the pandemic. USCIS suspended in-person services from March 17 to June 4, 2020, cancelling hundreds of thousands of biometrics appointments and preventing grants of green cards and naturalizations, which require in-person interviews. Even after resuming operations, social distancing practices slowed adjudications. New applications increased sharply in FY 2021, and by the end of the fiscal year USCIS had adjudicated 1.8 million fewer applications than it received.

Growing Backlogs at the State Department

The State Department has historically had less extensive backlogs than USCIS, but COVID-19 likewise had a significant impact. From an average of 60,900 immigrant visa applicants awaiting an in-person consular interview in 2019, the total increased to nearly 532,000 in July 2021. Office closures and social distancing measures were responsible for much of this growth. U.S. embassies and consulates around the world ceased visa processing in March 2020—with some limited exceptions for H-2 visas for temporary and seasonal workers, as well as visas for health professionals—and began a slow, phased reopening that July.

Even after reopening, however, many consular posts have operated at reduced capacity, with fluctuating work levels dependent on local vaccination rates, COVID-19 spread, and health restrictions. In January 2022, a little over one-quarter of U.S. consular posts remained closed for applications for nonemergency temporary visas, down from 60 percent in October 2021, however wait times can still sometimes stretch longer than six months. The interview backlog for permanent immigrant visas meanwhile recently fell slightly, to 436,700 requests for in-person interviews in February 2022.

Further Bottlenecks in Immigration Court

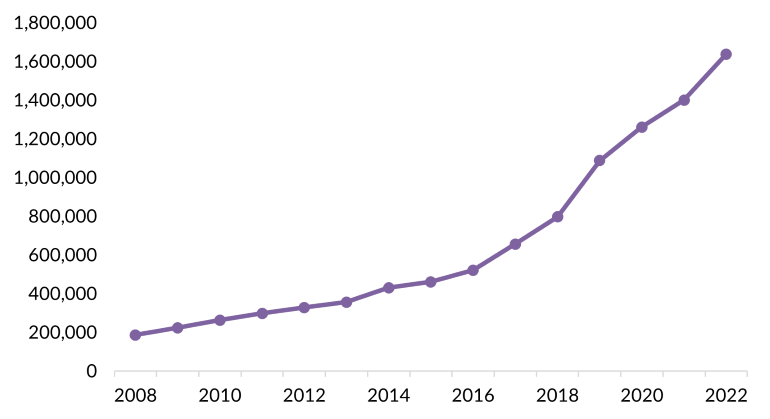

The backlog for hearings in immigration court has been on an upward swing for years, growing slowly between FY 2008 and FY 2016, from under 200,000 pending cases to about half a million, with the average wait time for a case rising from 438 days to 672 days. The courts failed to keep pace as new cases rose quickly starting in FY 2017, marking a rapid increase in the backlog. The caseload hit 1 million in FY 2019, during a year of high border arrivals, while average wait times grew to 696 days. Although more immigration judges were put in place, courts did not keep pace with the number of new cases added to their dockets.

Closures during the pandemic aggravated the challenges, with more than 1.6 million cases in the backlog as of January 2022 (see Figure 2). The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), the Justice Department agency that runs the immigration courts, suspended hearings for individuals who were not in immigrant detention from March 18, 2020 until June 2020 (hearings for detained immigrants continued). EOIR also suspended hearings for migrants who had been sent to Mexico to await their court dates through the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, also known as the Remain in Mexico program) from March 23, 2020 through the end of the Trump administration. (The Biden administration attempted to wind down the MPP program, but subsequently reinstated it under court order. The Supreme Court later this term will hear arguments in the case.) Although only 16 percent fewer cases were completed in FY 2020 than in FY 2019, the number of completed cases fell by half in FY 2021, from 231,800 to just 115,000. This dropoff likely reflects a mix of periodic court closures due to COVID-19 levels, policy shifts (discussed in further detail below), and changes in the types of cases before the courts.

Figure 2. Pending Cases in U.S. Immigration Courts, FY 2008-22

Note: Data for FY 2008 through FY 2021 reflect pending cases at the end of the fiscal year. FY 2022 data reflect the backlog as of January 2022.

Sources: Data for FY 2008 through FY 2021 are from Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions (2021), available online; Data for FY 2022 are from Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Immigration Court Backlog Tool,” accessed February 18, 2022, available online.

New Actions Add to the Workload

The easing of pandemic restrictions has offered some hope that these agencies might catch up on their backlogs, but new challenges have been presented due in part to the Biden administration’s expansion of TPS and the accompanying demand for employment authorization documents (EADs). USCIS is also processing work authorization for the more than 70,000 Afghans paroled into the United States following their evacuation from Afghanistan, and processing more than 42,000 humanitarian parole applications for Afghans still abroad. And it is also beginning to work through the 285,000 applications for U visas to determine those eligible for protection from removal and work authorization.

Furthermore, the anticipated new asylum regulation will require USCIS officials to take on a new caseload: adjudicating humanitarian protection claims of those who are apprehended at the border—a workload that could further surge if the administration ever ends the pandemic-related Title 42 border expulsions policy. The draft regulation could relieve some of the pressure on immigration courts that currently hear border asylum claims, but the courts are likely to retain some role reviewing appeals.

Backlogs Prompt Lawsuits

The backlogs have resulted in litigation against both USCIS and the State Department, forcing the government to respond to judicial orders and settlements that mandate processing timelines for certain types of cases—as a result, in a world of limited resources, affecting the agencies’ ability to establish their own priorities for processing backlogged cases. USCIS has been sued over its processing of work authorization documents for asylum seekers; foreign students seeking employment under the optional practical training (OPT) program; spouses of foreign workers on E-2, H-4, and L-2 visas; and people adjusting to green cards within the United States. Lawsuits against the State Department have targeted delays in visa processing during the pandemic.

As a result, USCIS in July 2020 agreed to a 120-day timeline for granting work permits to some students who applied for OPT for postgraduate work. In November 2021, it allowed spouses of E, H-1B, and L visa holders to have their work authorization automatically extended by 180 days while officials process renewal applications, and declared that spouses of E and L visa holders would not need a work authorization card because their status would automatically imply work authorization. However, lawsuits remain pending over USCIS’s slow processing of work permits.

Courts, meanwhile, have rejected pleas to speed up the State Department’s processing of K visas (for fiancés) and O-1 visas (for workers of so-called extraordinary ability or achievement), ruling that these visas were no more affected by pandemic-related slowdowns than any other category. Litigation on diversity visa processing was somewhat more successful, perhaps because of time constraints with the diversity visa lottery: In September 2020, a judge ordered the department to process as many diversity visa applications as possible before the end of the fiscal year and, recognizing that it would be unable to process all 55,000 allowed visas in time, set aside 9,095 visas for future years (the order to reserve these visas is on appeal). In September 2021, the same judge ordered the department to speed up diversity visa processing and set aside 481 diversity visas for the next fiscal year (the government has appealed that order). Diversity visa processing remains slow in FY 2022, and lawyers are preparing once again to sue.

Consequences of Backlogs: Slowed Immigration

Processing backlogs across the immigration system have affected the overall pace of immigration to the United States, alongside pandemic-related mobility restrictions. Legal immigration levels are far below normal: Grants of temporary visas dropped by 54 percent from FY 2019 to FY 2020 and then another 30 percent in FY 2021. Visas for new lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green-card holders) coming from abroad fell by 48 percent from FY 2019 to FY 2020, before rebounding slightly to 298,300 in FY 2021—still far below pre-pandemic levels.

Visas for seasonal H-2A and H-2B temporary workers remained steady over the pandemic, but those for higher-skilled visas dropped sharply; just one-third as many H-1B visas were issued in FY 2021 as FY 2019. This sharp slowdown in skilled immigration comes at a time when the United States is experiencing acute labor shortages. Processing delays, in addition, can contribute to longer stays abroad for those seeking re-entry visas, further contributing to workforce challenges and family separation.

USCIS delays mean that it can take more than 20 months to process some work permits, with repercussions for foreign workers and their employers. As a result, for example, some foreign students have been locked out of post-graduation jobs. Similarly, individuals holding DACA or TPS status and spouses of temporary immigrants have had have their employment suspended while waiting for new EADs. Perhaps the most unfortunate casualty of the processing delays were new DACA applicants who were eligible to apply in the brief window between its court-ordered reopening in December 2020 and subsequent court-ordered closure in July 2021; processing delays prevented the great majority of these applicants from being able to register.

Thanks to an obscure provision of immigration law, the administration’s challenges have resulted in a big shift from immigrants arriving through family-based channels to those coming via work. Processing delays in FY 2020 meant that tens of thousands of family-based green cards went unused, which by law became available to employment-based immigrants the following year. However, reduced administrative capacity meant that likely fewer than half of the 122,000 extra green cards available for employment-based immigration in FY 2021 were used; the remaining unused 69,000 or so green cards thus lapsed (precise figures were unavailable as of this writing). At the end of FY 2021, at least 140,000 of the 226,000 green cards available for family-preference categories were again unused due to processing delays, further exacerbating family-based backlogs but resulting in a new windfall for people waiting for employment-based visas.

Beginnings of Promising Adaptations

In recent months, new practices and policies have been introduced to address some of the processing backlogs. Through December 2023, the State Department will waive the requirement for a new in-person interview for green-card applicants who had been previously interviewed and issued visas but were unable to move to the United States because of the pandemic. Similar in-person interview requirements have been waived for certain students, exchange visitors, and high-skilled immigrants who have been approved for visas or would not have required them.

USCIS also has taken steps to increase efficiency, including extending work permit validity from one year to two for refugees, asylees, and parolees, among others. And a Trump administration policy requiring in-person interviews for all refugees and asylees applying to sponsor their spouses or children has been ended, returning to the previous practice allowing for officials’ discretion. Similarly, USCIS shortened the list of criteria indicating a refugee or asylee needed to undergo an in-person interview while applying for a green card. The agency also restored an old policy under which it generally defers to prior decision-making when considering an application for extension of status; during the Trump administration, such applications were given fresh scrutiny.

Furthermore, the agency has been substituting in-building video interviews for some required in-person interviews and conducting some refugee interviews remotely. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), however, has urged caution in the use of remote refugee interviews, recommending their use be limited and face-to-face interviews be prioritized when feasible.

Congress appropriated $250 million to address backlogs and support refugee processing at USCIS for FY 2022, part of which will go towards hiring 200 staff members for the agency’s asylum division. However, the vetting, hiring, and training of new employees takes time, so this funding will not yield immediate results.

For the immigration courts, Attorney General Merrick Garland has decided to again allow immigration judges to administratively close cases for individuals who are not a priority for removal, which permits the reduction of active cases on the docket. However, a shift away from the Trump administration’s setting of case quotas for all immigration judges could slow processing, even while advancing due process. The Biden administration is taking several steps to connect migrants with legal service providers, which can help avoid delays. EOIR has also introduced a new model that allows lawyers to provide written submissions for some matters instead of holding hearings in person, and also set shorter timelines for responses. This month, EOIR began requiring electronic, rather than paper, filings with immigration courts—a change that holds promise for greater efficiency if filing systems function well. Finally, in an attempt to speed the processing of cases for families apprehended at the border, the Biden administration has established a dedicated court docket for families in 11 U.S. cities; EOIR will attempt to resolve cases on this docket within 300 days of the initial hearing. To date, more than 70,000 people have been put into these dockets, but just 15 percent have legal representation.

For Meaningful Reform, Backlogs Must Be Addressed

These moves alone will not be sufficient to reverse mounting backlogs, yet doing so will be essential if the Biden administration wants its myriad immigration policy changes to bear fruit. Doing so will require substantial resources, yet USCIS is hamstrung by its reliance on application fees—a rarity among federal agencies. Congress would need to decide whether a consistent infusion of funding for some efforts, such as humanitarian applications, would result in a more effective immigration system. Despite earlier efforts at modernization, USCIS also remains archaically reliant on paper applications and records.

Immigration courts also rely on bulky paper files in an era where most records are electronic. Amid record backlogs, some have advocated dedicating some judges to more administrative matters such as master calendar hearings and continuances, or for specialized cases including juveniles.

The State Department plans to propose higher fees for immigration applications, which would allow it to increase staffing and improve efficiencies. Smarter prioritization and triaging of some cases, including dedicating officers for certain types, could be helpful in addressing backlogs.

Whatever the solutions, it is clear that the immigration system is buckling under its own weight. The Biden administration’s immigration changes have been significant. But many will not be realized if the government is unable to address the ever-rising backlogs across the immigration system—with ill effects for individual immigrants, their families, U.S. employers, and the credibility and integrity of the system as a whole.

Jessica Bolter provided research assistance for this article.

Sources

Amandeep Shergill et. al. v. Alejandro Mayorkas. 2021. No. 21-cv-1296-RSM. U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, Settlement Agreement, November 10, 2021. Available online.

American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA). 2019. USCIS Processing Delays Have Reached Crisis Levels under the Trump Administration. Policy brief, AILA, Washington, DC, January 2019. Available online.

---. 2021. Consent Order Issued in Li v. USCIS, a Class Action Lawsuit Challenging Certain OPT Delays—AILA Doc. No. 21072703. July 23, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Gomez v. Trump FAQ—AILA Doc. No. 20091614. March 16, 2021. Available online.

Alvarez, Patricia. 2021. Justice Department Eliminates Trump-Era Case Quotas for Immigration Judges. CNN, October 20, 2021. Available online.

Bier, David J. 2022. Record Nonimmigrant Visa Waits Even as 1/4 of Consulates Remain Partially Closed. Cato Institute blog post, January 20, 2022. Available online.

Bolter, Jessica, Emma Israel, and Sarah Pierce. 2022. Four Years of Profound Change: Immigration Policy during the Trump Presidency. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Mayorkas, Alejandro. 2021. Memorandum from the Secretary of Homeland Security to Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; Ur M. Jaddou, Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; and Troy A. Miller, Acting Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Worksite Enforcement: The Strategy to Protect the American Labor Market, the Conditions of the American Worksite, and the Dignity of the Individual. October 12, 2021. Available online.

Sanchez, Sandra. 2022. Bar Association Seeks Free Legal Counsel for Asylum-Seekers in Fast-Tracked Deportation Proceedings. Border Report, January 12, 2022. Available online.

Torrens, Claudia, Philip Marcelo, and Elliot Spagat. 2021. New Fast-Track Docket for Migrants Faces Familiar Challenges. Associated Press, November 11, 2021. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2022. Immigration Court Backlog Tool. Updated January 2022. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2021. Bona Fide Determination Process for Victims of Qualifying Crimes, and Employment Authorization and Deferred Action for Certain Petitioners. PA-2021-13. Camp Springs, MD: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2021. Number of Form I-918, Petition for U Nonimmigrant Status - By Fiscal Year, Quarter, and Case Status. October 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Number of Service-wide Forms by Quarter, Form Status, and Processing Time Fiscal Year 2021, Quarter 4. December 15, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Policy Alert: Deference to Prior Determinations of Eligibility in Requests for Extensions of Petition Validity. PA-2021-05. Camp Springs, MD: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2021. USCIS Reverts to Previous Criteria for Interviewing Petitioners Requesting Derivative Refugee and Asylee Status for Family Members. Press release, December 10, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. USCIS Announces FY 2021 Accomplishments. Press release, December 16, 2021. Available online.

---. 2022. Readout of Director Ur M. Jaddou’s Virtual Briefing with Stakeholders to Mark One-Year Anniversary of Executive Orders Aimed at Restoring Faith in Our Immigration System. Press release, February 2, 2022. Available online.

---. N.d. Check Case Processing Times. Accessed February 15, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). 2021. Administrative Closure. November 22, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Executive Office for Immigration Review Electronic Case Access and Filing. Federal Register 86, no. 236 (December 13, 2021): 70708–70725. Available online.

---. 2021. Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions. October 19, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Revised Case Flow Processing Before the Immigration Courts. April 2, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of State. 2021. Important Announcement on Waivers of the Interview Requirement for Certain Nonimmigrant Visas. Updated December 23, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Waiver of Personal Appearance and In-Person Oath Requirement for Certain Immigrant Visa Applicants Due to COVID-19. Federal Register 86, no. 236, December 13, 2021: 70735-40. Available online.

---. N.d. Report of the Visa Office 2020. Table 1: Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Visas Issued at Foreign Service Posts: Fiscal Years 2016 – 2020. Accessed February 14, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of State, National Visa Center (NVC). 2022. Immigrant Visa Backlog Report. Updated February 2022. Available online.