You are here

For Vulnerable Immigrant Children, A Longstanding Path to Protection Narrows

More than 70,000 immigrant children have applied for Special Immigrant Juvenile status since fiscal year 2010, including many from Central America. (Photo: Kevin Chang)

Nearly 210,000 unaccompanied immigrant children were detained at the U.S.-Mexico border between fiscal years (FY) 2014 and 2017, the majority coming from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Most of these arriving unaccompanied minors do not meet the stringent requirements for receiving asylum in the United States. However, some are eligible for Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status, a pathway to lawful permanent residence (also known as getting a green card) for immigrant children who have been abused, abandoned, or neglected by their parents.

SIJ was designed to protect vulnerable immigrant youth. However, several factors make it difficult to access this form of protection. Discrepancies between state and federal law have caused some youth between the ages of 18 and 21 to fall through the cracks. New standards for adjudicating SIJ applications have also led to the rejection of hundreds of applicants. And in recent years, policy changes and a growing number of applicants have resulted in a dramatically slowed processing rate—leaving some SIJ-eligible youth in limbo, without legal status, for years.

This article provides an overview of the SIJ program and its growth as a pathway to protection for immigrant children. Drawing on a series of interviews with immigrant youth, adult sponsors, attorneys, and judges, it also identifies limitations on access to SIJ.

Protecting Abused Children

The Immigration Act of 1990 originally established SIJ as a narrow form of legal relief for immigrant children in the foster-care system. In 2008, the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) expanded the scope of SIJ by creating additional avenues to eligibility.

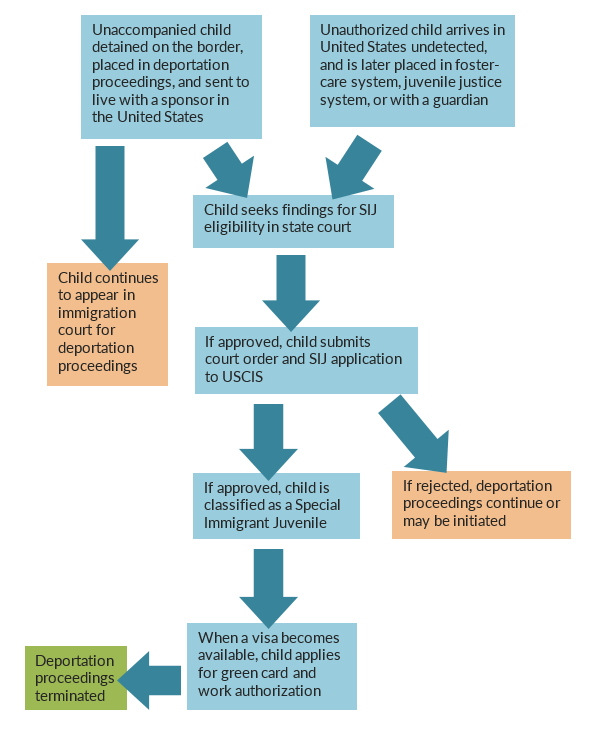

Under federal law, foreign nationals preliminarily qualify if they are under the age of 21 and unmarried. To apply, a child must first petition a state court judge to make several legal findings: that he or she is unable to reunify with one or both parents due to abuse, abandonment, or neglect; that he or she should be placed under the guardianship or custody of an individual or government agency; and that it is in the child’s best interest to remain in the United States.

Once a state court makes these determinations, the child can submit an SIJ application to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). If the application is approved, the child may then apply for a green card, and after five years as a legal permanent resident, for U.S. citizenship.

Figure 1. Steps in the Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) Process

Source: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Special Immigrant Juveniles,” updated April 10, 2018, available online.

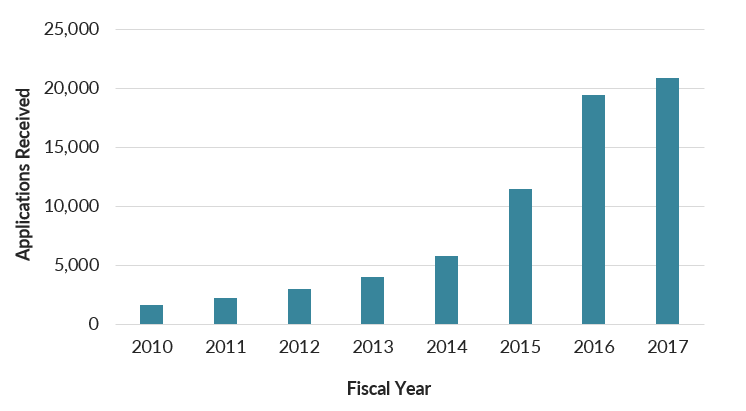

Since FY 2010, more than 70,000 people have applied for SIJ. Applications gradually increased in 2010 and the next several years, and then grew significantly in 2015 after a surge in arrivals of unaccompanied children at the Southwest border in 2014 (see Figure 2). Nearly 21,000 applications were filed in FY 2017 alone. Many unaccompanied children are detained on the border, transferred to live with family members in the United States, and then apply for SIJ while their deportation proceedings are pending.

Figure 2. Special Immigrant Juvenile Applications by Fiscal Year, 2010-17

Source: USCIS, “Number of I-360 Petitions for Special Immigrant with a Classification of Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) by Fiscal Year and Case Status, October 1 - December 31, 2017,” updated May 1, 2018, available online.

Limitations on SIJ Access

Methodology

This article draws upon research that began in the summer of 2017. The author conducted interviews with 23 young immigrants who were in the process of applying for or had received SIJ status, 23 attorneys who represent children in SIJ cases, eight adult guardians of eligible youth, and three state court judges. Interviews were conducted across the United States, with participants from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New York, Virginia, and Washington.

Interviews with stakeholders identified three major limitations on access to SIJ and its corresponding benefits: Variations in state court jurisdiction, as well as two recent trends narrowing access—changes in USCIS decision-making and a growing green-card backlog.

Variations in State Court Jurisdiction

Differences in how state courts handle youth mean that an immigrant’s ability to access SIJ can depend on where he or she lives. For a state court judge to make findings pursuant to a child’s eligibility for SIJ, the judge must have jurisdiction over the child in one of four major areas of proceedings: guardianship, custody, dependency, or delinquency. Courts in most states only have jurisdiction over children in these areas until the age of 18, at which point children cease to be legally defined as minors. Thus, even though SIJ eligibility under federal law lasts until age 21, many immigrants cannot apply after turning 18 because they cannot obtain the required state court findings.

To address this gap, at least five states have passed laws allowing immigrant youth to petition for SIJ findings until age 21. New York amended its family law in 2008 to allow anyone to obtain a legal guardian until age 21, while in 2014 and 2015, Maryland and California extended the court jurisdiction age to 21 exclusively for SIJ applicants in certain proceedings.

USCIS Decision-Making

Another, more recent barrier to SIJ occurs during the adjudication process, once the application is with USCIS. For many years, this part of the process was largely routine. The approval rate for SIJ applications hovered around 95 percent every year until 2016. Applications were generally adjudicated within six months, as mandated by TVPRA.

But in October 2016, USCIS began applying new standards and enhanced scrutiny to SIJ applications, fundamentally changing the process. Soon after, it also started adjudicating all applications in the National Benefits Center, centralizing a formerly regional process in which local USCIS offices reviewed applications from their own areas.

Attorneys and judges have since reported receiving far more Requests for Additional Evidence (RFEs) from USCIS in SIJ cases. Pointing to the October 2016 guidance, these RFEs generally ask for further proof of parental mistreatment of the child or for clarification on matters of court jurisdiction.

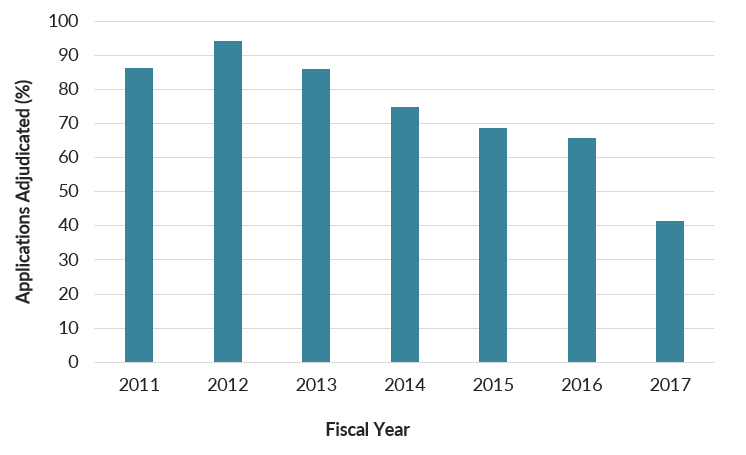

Increased issuance of RFEs appears to be slowing down SIJ processing, as is happening in other visa categories as well. While the adjudication rate had been falling gradually since 2012 as more and more applications were received, it dropped faster in 2017 just after these new policies took effect (see Figure 3). USCIS issued a final decision for nearly 42 percent of pending applications in FY 2017, down from 66 percent a year earlier.

Figure 3. Adjudication Rate for Special Immigrant Juvenile Applications, (%), FY 2011-17

Note: Adjudication rate was calculated by dividing the total number of applications for which a final decision was made (accepted or denied) in a given fiscal year by the sum of the number of applications filed that year and the number of applications pending from the previous year.

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) analysis of data from USCIS, “Number of I-360 Petitions for Special Immigrant with a Classification of Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) by Fiscal Year and Case Status October 1-December 31, 2017,” updated May 1, 2018, available online.

In the first half of 2018, USCIS has also begun systematically denying SIJ applications for youth 18 and older. A USCIS spokesman told Politico in late April that roughly 260 of these applications had been denied nationwide based on new USCIS guidance distributed in February 2018 but not publicly released, and that an additional 5,500 applications were on hold pending review. Attorneys in New York and California reported having clients who were denied for this reason, and it is likely that similar denials will occur or have already occurred in other states that allow immigrant youth in this 18-to-21 age group to apply.

While the denial language has varied slightly across regions, the rationale is the same. USCIS argued in several cases that state courts generally lack the authority to make decisions about the care and custody of individuals over age 18 for the purposes of SIJ eligibility. Even when state laws permit youth to seek a guardian until age 21, those laws, according to USCIS, do not authorize the state courts to declare parental reunification unviable—and therefore the courts cannot determine SIJ eligibility for immigrants 18 and older.

Lawyers in New York filed a class-action lawsuit in June 2018 against USCIS. Plaintiffs, including several affected youth and the Legal Aid Society of New York, allege the denials are illegal, taking place without any change in the underlying law. In support of the lawsuit, 15 Democrats in Congress filed an amicus brief arguing U.S. immigration law clearly stipulates that USCIS should defer to state courts on matters related to the best interests of the child.

These trends have provoked anxiety among SIJ applicants. As cases drag on for years, attorneys say that many of their clients become restless and stop showing up for meetings. A New York lawyer said that her clients who recently received denials are terrified of being deported because they handed over their address and other personally identifying information to the federal government.

Green-Card Backlog

In addition, a severe backlog in green-card applications for immigrants from countries with significant immigration to the United States has resulted in a bottleneck in the SIJ process. After their SIJ applications are approved by USCIS, immigrant youth must then file an application for a green card. SIJ falls under the fourth employment-based visa category (EB-4), which is capped at 9,940 green cards per year and includes other “special” immigrant categories, including religious workers and Iraqi and Afghan nationals who aided the U.S. government. Additionally, no more than 7 percent of preference-category green cards can be allocated to individuals from a country in a given year. Thus, the number of green cards that can be given each year to SIJ recipients is limited.

In May 2016, the State Department announced a green-card application cut-off date for individuals from countries that were close to exceeding the per-country cap—namely, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. This “priority date” is moved forward periodically, creating a process by which SIJ recipients from the high-demand countries apply for permanent residence on a staggered timeline. As a result, wait times for immigrants from the affected countries began to grow.

The backlog, which now also includes India and Mexico, is having a significant impact on SIJ-eligible youth. While they could previously file their green-card applications at the same time or immediately after their SIJ applications, those from the affected countries must now wait up to three years or more from the time their SIJ applications are approved to when they can apply for a green card. As a result, youth are stuck in legal limbo without any official status.

Of the 23 young immigrants interviewed, 18 were affected by the backlog. Most cited the inability to obtain work authorization as the most detrimental effect. Typically, youth file their work-permit applications alongside their green-card applications, and can work while they wait to be granted permanent residence. But those who cannot apply for green cards until their priority date must also wait until then to request work authorization.

Many have adapted by simply not working at all, despite being of legal working age. The constraint has been particularly hard on youth who graduated from high school or are ineligible to enroll due to their age. Others have resorted to working illegally, generally in construction or cleaning. Higher education is often out of reach, because SIJ applicants cannot receive federal financial aid without legal status. One young man interviewed excelled in school and said he dreamed of joining the Navy, but would have to wait until he obtained a green card.

As SIJ applicants wait, they must grapple with the backlog’s most frightening implication: the persistent threat of deportation. Although SIJ classification puts the young person on a path to permanent residency, it does not provide any official immigration status, nor does it legally protect from deportation. Thus, youth in removal proceedings who have been approved for SIJ but are waiting for a green card can still be deported in the interim period.

Before the green-card backlog grew significantly in 2016, immigration judges generally agreed to terminate or suspend removal proceedings against unauthorized youth approved for SIJ. However, attorneys interviewed in California, Maryland, Virginia, and New York said that immigration judges have stopped granting such requests for youth who remain without status indefinitely due to the green-card backlog.

At the same time, guidance from Chief Immigration Judge MaryBeth Keller in 2017 and Attorney General Jeff Sessions in 2018 has put pressure on immigration judges to speed up cases and postpone removal only sparingly. As a result of these changes, young immigrants report fearing deportation every time they show up for court.

Advocating for SIJ Applicants

Stakeholders involved with SIJ have recommended several ways to make the process work better for children seeking protection.

Advocates are suggesting that USCIS should grant deferred action to SIJ recipients awaiting their green cards. Deferred action provides temporary relief from deportation and access to work authorization, as occurs for recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Attorneys for SIJ applicants note granting deferred action to their clients would be consistent with treatment for similar classes of vulnerable immigrant adults, such as those abused by their spouses and approved for Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) status. They also are calling on USCIS to allow SIJ recipients to seek and obtain work authorization before applying for their green cards. Several immigrant groups protected by deferred action, such as VAWA recipients and DACA holders, also can apply for work authorization.

While acknowledging that USCIS has the right to create its own standards for adjudicating SIJ applications, interviewed judges argued that the agency should defer to them on matters of state law. As stakeholders pointed out, Congress authorized state court judges, not USCIS, to make decisions about the care and custody of juveniles for purposes of SIJ eligibility. Thus, if a judge issues a finding of jurisdiction over a child and determines the child to be eligible for SIJ, they argue that USCIS should not have the authority to second-guess the decision.

An Uncertain Future

As advocates and some state governments seek to expand access to SIJ, other groups are trying to restrict it. Opponents argue that the SIJ program invests too much authority in state courts, which are unable to sufficiently scrutinize children’s claims regarding parental mistreatment that occurred in a different country.

Republican lawmakers have attempted on multiple occasions to narrow eligibility for SIJ as part of a larger effort to close perceived “loopholes” in the U.S. immigration system. In 2017, House Republicans introduced two bills addressing SIJ: one redefining “unaccompanied minor” to exclude children with a parent or close relative in the United States, and another that would require SIJ applicants to demonstrate that reunification is not viable with both of their parents, rather than just one.

Meanwhile, some critics of the program allege that parents make false claims of abuse to keep their children in the United States, and that in other cases both parents arrange and fund the youth’s journey themselves. In 2015 a local news station in New York reported on alleged fraud by hundreds of young men arriving from the same region of India, who told “similar stories” at the Queens Family Court in pursuit of SIJ. The report quoted a judge as saying the court does not “have a way of investigating” the testimony given by applicants.

Still, advocates insist that the law is an essential mechanism for preventing the deportation of abused children to dangerous conditions and placing them in safe homes in the United States. Amid rapidly evolving immigration policy changes and advocacy on both sides of this program, it remains to be seen whether SIJ will continue to be a viable alternative to asylum for a significant number of vulnerable immigrant children, or whether it will become a narrower form of protection for a relative few.

Sources

Bronstein, Sarah, and Michelle Mendez. 2016. Strategies for SIJS Cases in Light of Adjustment Backlog. Silver Spring, MD: Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc. Available online.

Gauto, Martin. N.d. USCIS Centralizes SIJS Adjudications. Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc., accessed May 1, 2018. Available online.

Hesson, Ted. 2018. Travel Ban at SCOTUS. Politico, April 25, 2018. Available online.

Immigration Act of 1990. Public Law 101-649. U.S. Statutes at Large 104, 1990.

Meckler, Laura. 2018. New Quotas for Immigration Judges as Trump Administration Seeks Faster Deportations. The Wall Street Journal, April 2, 2018. Available online.

Moran, Greg. 2017. Number of Juveniles Gaining Special Immigration Status from Federal Authorities Doubled in 2016. San Diego Union-Tribune, May 28, 2017. Available online.

Morton, John. 2011. Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion Consistent with the Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities of the Agency for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Aliens. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) memo, July 17, 2011. Available online.

Keller, MaryBeth. 2017. Operating Policies and Procedures Memorandum 17-01: Continuances. Department of Justice memo, July 31, 2017. Available online.

Ramey, Corinne. 2018. Lawsuit Claims Some Young Immigrants Treated Unfairly Under New Policy. The Wall Street Journal, June 7, 2018. Available online.

Robbins, Liz. 2018. A Rule is Changed for Young Immigrants and Green Card Hopes Fade. New York Times, April 18, 2018. Available online.

Russo, Melissa, Evan Stulberger, and Fred Mamoun. I-Team: Family Court Exploited in Immigration Cases in Queens, Insiders Charge. WNBC, March 4, 2015. Available online.

Semple, Kirk. 2015. Federal Scrutiny of a Youth Immigration Program Alarms Advocates. New York Times, March 31, 2015. Available online.

State of California. 2015. Juveniles: Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. Assembly Bill 900, Chapter 694. Approved by Governor, October 9, 2015.

State of Maryland. 2014. Equity Court Jurisdiction - Immigrant Children - Custody or Guardianship. House Bill 315, Chapter 96. Approved by Governor, April 8, 2014.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2016. Battered Spouse, Children, and Parents. USCIS, updated February 16, 2016. Available online.

---. 2016. Policy Alert: Special Immigrant Juvenile Classification and Special Immigrant-Based Adjustment of Status. USCIS, October 26, 2016. Available online.

---. 2018. Special Immigrant Juveniles. USCIS, updated April 10, 2018. Available online.

---. 2018. Number of I-360 Petitions for Special Immigrant with a Classification of Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) by Fiscal Year and Case Status, October 1 – December 31, 2017. USCIS, updated May 1, 2018. Available online.

---. 2018. Policy Manual: Vol. 6, Part J – Special Immigrant Juveniles. USCIS, updated May 2, 2018. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman (CISOMB). 2015. Ensuring Process Sufficiency and Legal Sufficiency in Special Immigrant Juvenile Adjudications. Washington, DC: CISOMB. Available online.

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives. Asylum and Border Protection Act of 2017. H.R. 391. 115th Cong., 1st sess. Introduced January 10, 2017.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2018. Border Patrol Total Monthly UACs by Sector, FY10-FY17. CBP, updated July 2018. Available online.

William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008. Public Law 110-457. U.S. Statutes at Large 122, 2008.