Why Immigrants Lack Adequate Access to Health Care and Health Insurance

The high costs of health care and the erosion of health insurance coverage are two important long-term challenges that confront all Americans. These problems are especially acute for immigrants to the United States, who have extremely low rates of health insurance coverage and poor access to health care services.

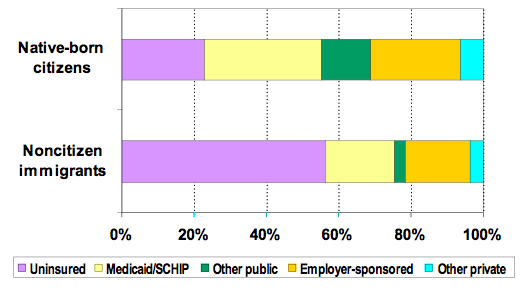

In fact, almost half of all immigrants — here defined as noncitizen immigrants — are uninsured, a level that is about three times higher than for native-born citizens. Because so many immigrants lack insurance, they face serious barriers to medical care and pay more out-of-pocket when they receive care.

In addition to the obvious health and humanitarian concerns associated with poor health care access, other economic and social reasons cause concern. Unresolved health problems can limit immigrants' ability to maintain productive employment, particularly given that many work in physically strenuous jobs or in jobs in which there is a high incidence of occupational injuries.

Because so many immigrants lack the protections of health insurance, the cost of even a single hospitalization can drive many into debt and financial insolvency. The Institute of Medicine, a component of the National Academy of Sciences, has estimated that lack of health insurance in the United States costs between $65 and $130 billion per year, due to health impairments and years of productive life lost of all uninsured, not just immigrants.

Immigrants, both legal and unauthorized, often rely on a patchwork system of safety-net clinics and hospitals for free or reduced-price medical care, including state- and county-owned facilities, as well as charitable and religiously affiliated facilities. Their reliance on this system has led many states and communities to be concerned about uncompensated health care costs for uninsured immigrants and the state and local fiscal burdens that result.

This paper summarizes key issues and research concerning immigrants' access to private health insurance, public health insurance, and to health care in general.

Data on Immigrants' Access to Health Insurance

U.S. census data show that immigrants are more likely to be uninsured than native-born citizens (see Table 1). Overall, noncitizen immigrants are more than three times as likely to be uninsured (44 percent) as native-born citizens (13 percent). The percent of naturalized citizens who are uninsured (17 percent) is between that of noncitizens and native citizens.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recent immigrants are more likely to be uninsured. Over time, their rates of insurance improve and their incomes grow. This is partly because immigrants tend to find better-quality jobs with time, and partly because both citizens' and immigrants' incomes increase with age and greater job experience. The main reason immigrants are less insured than native-born citizens is that, despite their high rates of employment, fewer immigrants have employer-sponsored health insurance.

The discrepancy between immigrants and native-born citizens persists among those with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line (about $33,000 per year for a family of three in 2006). Among the low-income category, 56 percent of noncitizen immigrants are uninsured versus 23 percent of native-born citizens (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

However, reasons for the insurance gap change when considering the low-income population. The primary reason for the difference in coverage between low-income immigrants and citizens is that fewer immigrants have public coverage, including Medicaid (which serves the poor) and Medicare (which serves the elderly). Low-income immigrants are also less likely to have employer-sponsored coverage and other private coverage, but the gaps are somewhat narrower.

|

|

||

|

Although census data do not reveal whether immigrants are legal or not, it is important to recognize that these profiles are affected by the types of immigrants living and working in the United States. Analyses by the Pew Hispanic Center indicate that annually, the proportion of immigrants who are unauthorized has grown in recent years, causing the proportion of those legally admitted to fall. Unauthorized immigrants are ineligible for public benefits (except for limited Medicaid coverage for treatment of emergency medical conditions) and have greater difficulty securing private health insurance as well.

Access to Private Health Insurance

Employer-sponsored insurance is the mainstay of health coverage for most Americans, but not for immigrants. Analyses of census data have found that a key reason for this lack of coverage is that immigrant workers, particularly Latino immigrants, are less likely to be offered insurance at work than citizen workers.

Job-based health insurance is offered to 87 percent of non-Hispanic white citizen workers, but only to 50 percent of Latino immigrant workers. However, when they are offered health insurance, comparable numbers of white citizens and Latino immigrants accept the offer and take employer-sponsored insurance (87 percent of white citizen workers and 81 percent of Latino immigrant workers).

In most cases, accepting the insurance offer means immigrant employees are also willing to bear a portion of the costs in the form of employee premiums and other cost-sharing mechanisms. The offer and acceptance rates for Latino citizen workers are about the same as those for non-Hispanic white citizens.

Part of the reason immigrants are offered insurance at lower rates is that they frequently work in the types of industries that are less likely to offer health insurance, such as agriculture, construction, food processing, restaurant, hotel, and other service jobs. But more detailed analyses have shown that even after statistically adjusting for differences in job type, salary level, and other factors, immigrants are still less likely to be offered insurance.

In some cases, employers may be able to effectively treat immigrants — even legal immigrants — differently by classifying them as contract, temporary, or part-time workers, so they are not required to offer benefits.

Moreover, rather than directly hiring workers (e.g., farm workers, janitorial staff, etc.), some firms instead pay contractors for labor, knowing that contractors lower their costs by not offering benefits to their employees. A recent report found that, regardless of citizenship, 21 percent of contract, temporary, and part-time workers had health insurance compared with 74 percent of full-time regular workers.

It is not clear whether discrimination is a cause, meaning that within the same company, immigrants are not offered health insurance offered to citizen workers, or whether immigrants tend to work in firms that generally do not offer insurance.

Under federal law, employers are supposed to offer health insurance on equivalent terms to all their workers, but it is plausible that immigrants, particularly unauthorized workers or temporary visa holders, are often not offered health benefits on terms equivalent to other workers.

Access to Public Health Insurance

For most low-income people in the United States, Medicaid is the mainstay of health insurance coverage. But not all immigrants are eligible for Medicaid and its counterpart, the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

The 1996 welfare reform law prohibited most lawful permanent residents admitted after the law's enactment from receiving federal Medicaid or SCHIP coverage during their first five years in the United States; similar prohibitions also barred eligibility for other benefits such as food stamps, welfare, and supplemental security income. About 40 percent of all lawful permanent residents in the United States today entered after 1996 and have been subject to this prohibition.

Unauthorized immigrants and temporary visa holders (e.g., those with student or temporary work visas) are not eligible for Medicaid, except for Medicaid coverage of emergency room services. Elderly immigrants, though often ineligible for Medicare because they did not work in the United States for a sufficient number of years to qualify for it or Social Security, may still be eligible for Medicaid if they are poor enough and meet other criteria.

Beginning in the late 1990s, the federal eligibility prohibition — combined with fears in the immigrant community that getting Medicaid or SCHIP could harm an immigrant's chance of getting lawful residence, remaining in the United States, or becoming naturalized — discouraged participation even among those eligible for public benefits. The federal government subsequently clarified that getting Medicaid or SCHIP benefits would not make an immigrant ineligible for permanent residency.

Nonetheless, since welfare reform's 1996 enactment, low-income immigrants have lost Medicaid coverage and are more likely to be uninsured. A number of states opted to cover some of these immigrants, particularly children or pregnant women, using state funds.

Federal legislation that passed in early February 2006 adds a new requirement that American citizens applying for or already enrolled in Medicaid must submit proof of citizenship, such as a U.S. passport or birth certificate. This provision would not apply to immigrants applying for Medicaid, who must already submit documentation of their legal status. Although the legislation is aimed at citizens, it could have repercussions for immigrants as well if it leads many in the immigrant community (and some caseworkers) to believe they must also show proof of citizenship to obtain coverage.

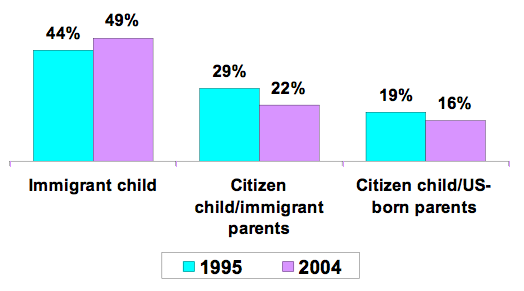

Beyond the adult immigrant population, gaps in insurance coverage between immigrant children and citizen children widened over the past decade (see Figure 2). After the 1996 immigrant prohibitions, more immigrant children became uninsured.

|

|

||

|

In contrast, the enactment of SCHIP in 1997 and subsequent state efforts to expand children's coverage with SCHIP and Medicaid led to higher insurance coverage of citizen children. As a result, the percentage of low-income children in native-born families who were uninsured fell from 19 percent in 1995 to 16 percent in 2004. Immigrant children did not benefit from these expansions, however, largely because they could not participate in them; the percent of low-income immigrant children who were uninsured climbed from 44 percent in 1995 to 49 percent in 2004.

Initially, even though U.S.-born children were eligible, families with such children dropped out of Medicaid and SCHIP due to their fears about welfare reform. But as Figure 2 shows, this problem has eased thanks in large measure to substantial outreach and educational efforts on the part of state and local governments and community-based organizations. Consequently, the coverage of children in mixed-status families has improved, even though they are still more likely to be uninsured than children with native-born parents.

The Role of Immigrant Sponsors

The 1996 prohibition on Medicaid and SCHIP coverage was based on some legislators' belief that sponsors of immigrants ought to be responsible for their health insurance coverage. Since 1997, those who sponsor immigrants must agree to be responsible for them and are informed that they may be held liable for the costs of public assistance, like Medicaid or SCHIP, if the sponsored immigrants receive benefits. Expectations that most recent immigrants could get private insurance from employers or that their sponsors would step in to provide other private coverage have proven to be unrealistic.

While sponsors may be able to provide financial support in some areas, it can be quite difficult for sponsors to afford health insurance for the immigrants they have sponsored. In 2005, the price of an average, employer-sponsored health insurance policy for a family was over $10,000; for an individual, the cost of such a policy was over $4,000. The prices can be even higher when insurance must be purchased on a nongroup basis, as would be required for those who are not in the sponsors' immediate families.

Many Americans are themselves uninsured, and sponsors with low- and middle-incomes usually cannot afford the health insurance of those they sponsor. The prohibition on Medicaid coverage for legal immigrants during their first several years in the United States effectively means that a large number of immigrants are uninsured, even if they are working and have serious health needs.

Access to Health Care

Because immigrants are so often uninsured, out-of-pocket health care costs are higher than those paid by the insured, making immigrants less able to pay for the care they need. Other factors, like language barriers, also impair immigrants' access to and the quality of medical care they receive. The net result is that immigrants are much less likely to use primary and preventive medical services, hospital services, emergency medical services, and dental care than are citizens, even after controlling for the effects of race/ethnicity, income, insurance status, and health status.

Low-income immigrant adults are twice as likely as low-income, native-born citizen adults to report that they have no regular source of health care according to a study published in 2001 by Leighton Ku and Sheetal Matani. Similarly, low-income immigrant children are four times more likely to lack a usual source of care as low-income children with native-born citizen parents.

A report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently concluded that racial/ethnic disparities in health care are gradually narrowing between African Americans and white Americans but are widening between Latinos and non-Hispanic white Americans. The poor health care access of immigrant Latinos is a major reason for this widening gap in medical care.

What little is known about the health care access of unauthorized immigrants suggests that it is particularly poor. One broad survey of California farm workers by researcher Don Villarejo and published in 2000 found that only one-sixth were offered employer-sponsored health insurance, and one-third of those receiving offers of coverage said they could not afford the insurance offered. Half of the males and one-third of the females had not seen a physician in the past two years, even though many had occupational illnesses or chronic health problems like high blood pressure and anemia.

Sociologist Abel Valenzuela and a team of researchers found a high level of occupational injuries in their 2003-2004 national survey of day laborers, who are predominantly unauthorized. One-fifth of day laborers had suffered a work-related injury, but less than half received medical care for that injury.

Because some public health care facilities inquire about immigration status, immigrants believe that seeking treatment at such facilities could lead to problems with immigration officials. Thus, some immigrants turn to black-market sources of health care, such as unlicensed health care providers (e.g., immigrant doctors not licensed to practice in the United States), and may purchase prescription drugs that have been smuggled into the United States.

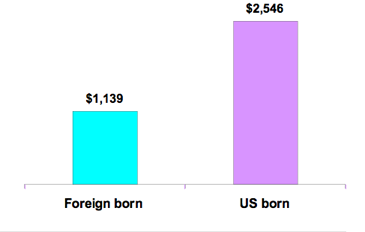

Some worry that the costs of medical care, especially emergency care, for immigrants is creating excessive financial strain on the nation's health care system. Yet, a recent study by Dr. Sarita Mohanty, which was based on data from the late 1990s, found that, per capita, medical expenditures for immigrants were about 55 percent lower than those of U.S.-born individuals (see Figure 3). Expenditures for uninsured and publicly insured immigrants were also approximately half those of their U.S.-born counterparts.

Other research, conducted by the Urban Institute and the Center for Studying Health Systems Change and published in 2006, has shown that immigrants are much less likely to use emergency rooms than native-born citizens. Indeed, border areas with high concentrations of immigrants may sustain high uncompensated care costs because so many immigrants are uninsured.

|

|

||

|

The federal government recently began to reimburse hospitals for uncompensated emergency care costs incurred by uninsured, unauthorized immigrants. In 2005, its first year of operation, the federal government paid $58 million to assist these providers.

A large share of other, uncompensated health care costs is borne by state and local governments or charitable or religious organizations that operate the facilities. And some costs are also indirectly transferred to those with private insurance, who bear somewhat higher health care costs when hospitals or other facilities cross-subsidize their losses from uncompensated care for uninsured people by charging private health insurers more.

Potential for Change

The present congressional debate over immigration reform offers the opportunity to improve immigrants' access to health care, both because it could change the legal status of large numbers of immigrants and because it affords a window for Congress, advocates, and analysts to review other policies concerning the status of immigrants in the United States.

Of course, it is not yet clear what direction immigration reform will take. It is conceivable that a new policy could make health care access more difficult for many immigrants, for example, by further restricting access to public benefits, limiting access to safety-net facilities, or making it illegal for health or social service providers to offer assistance to unauthorized immigrants.

On the other hand, if a new policy provides options for legalized status, it could improve immigrant workers' employment prospects and thereby raise their opportunities to secure private, employer-sponsored insurance.

This article is based on Leighton Ku and Demetrios G. Papademetriou's report for the Independent Task Force on Immigration and America's Future. The report is part of a volume entitled Securing the Future: U.S. Immigrant Integration Policy, A Reader.

Sources

Cunningham, Peter (2006). "What Accounts for Differences in the Use of Hospital Emergency Departments in Communities Across the United States?" Health Affairs web exclusive, July 18.

Fremstad, Shawn and Laura Cox (2004). "Covering New Americans: A Review of Federal and State Policies Related to Immigrants' Eligibility and Access to Publicly Funded Insurance." Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November.

Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the National Council of La Raza (2006). "The Role of Employer-Sponsored Health Coverage for Immigrants: A Primer." Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, June.

Ku, Leighton and Sheetal Matani (2001). "Left Out: Immigrants' Access to Health Care and Insurance." Health Affairs 20, no. 1. Jan/Feb: 247-56.

Mohanty, Sarita et al. (2005). "Health Care Expenditures of Immigrants: A Nationally Representative Analysis." American Journal of Public Health 95, no. 8. Aug: 1431-1438.

Schur, Claudia and Jacob Feldman (2001). "Running in Place: How Job Characteristics, Immigrant Status, and Family Structure Keep Hispanics Uninsured." New York City: Commonwealth Fund, May.

Valenzuela, Abel, Nik Theodore, Edwin Meléndez and Ana Luz Gonzalez (2006). "On the Corner: Day Labor in the United Status." January. Available online.

Villarejo, Don. et al. (2000). "Suffering in Silence: A Report on the Health of California's Agricultural Workers." Woodland Hills, CA: California Endowment.