You are here

No Retreat: Climate Change and Voluntary Immobility in the Pacific Islands

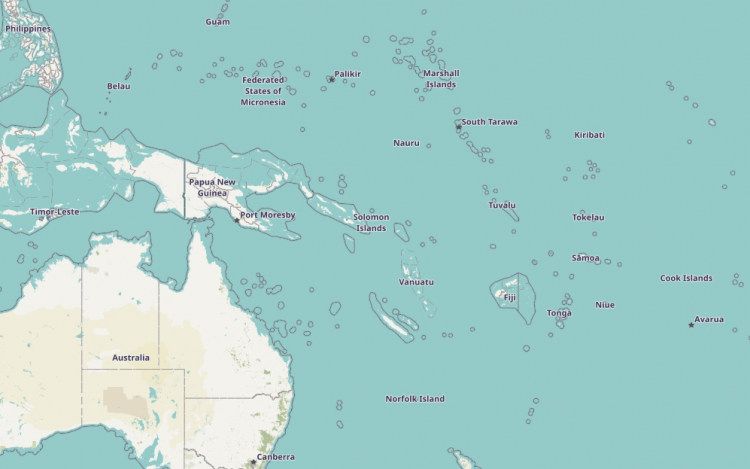

Some Pacific Island nations, including Kiribati and Tuvalu, will likely become entirely submerged due to rising sea levels. (Photo: Global Environment Facility)

Climate change in certain contexts can be a driving factor in human mobility, particularly in low-lying coastal areas. In mainstream climate adaptation thinking, physical retreat from highly vulnerable places is assumed to be inevitable in some circumstances—when adaptation measures have been exhausted. The potential scale of these movements has long been sensationalized in media and some activist, policy, and academic narratives, which grimly predict mass displacement of “climate refugees” from low-lying areas toward inland regions. One such projection estimates a worst-case scenario in which rising sea levels could push up to 2 billion people off their land by 2100.

Critics argue that these predictions are overly simplistic, lack scientific rigor, and are often rooted in technocratic, paternalistic, and Western modes of thinking. This doomsday discourse, which posits affected populations as “refugees,” is generated largely by outsiders relative to the places most vulnerable to climate change. Further, the decisions individuals make to flee climate impacts—and therefore, the eventual number who will leave—are complex and rarely driven by climate change alone.

Such decisions, and the ensuing migration trajectories that might be expected, can be more fully and accurately understood by focusing on the perspectives of affected people. The question of forced or voluntary migration, while important, is far from the whole story. More effort should be made to learn what retreat, or lack thereof, means to populations with unique and specific attachments to place. From such a perspective, climate mobility is currently poorly understood as an emerging social phenomenon. The victimhood narrative erases the agency of affected groups—particularly the exercise of a choice to stay, to be voluntarily immobile. Some households and communities may choose not to leave, even if in-situ adaptation options no longer exist. Factors influencing this decision include cultural, historical, and spiritual attachments to place, and political considerations such as self-determination.

Understanding these immobile groups and their decision-making calculus is an important task. To date, while migration and relocation are often assumed, voluntary immobility is less anticipated, understood, or planned for when adaptation on site has run its course.

This article explores preliminary ideas about voluntary immobility, drawing on its emergence as a choice and a policy concern in the Pacific Islands. It explores the potential for voluntary immobility as a concept to expand debates on climate-change migration and relocation, considering the felt needs of impacted groups. This agenda complements an emerging recognition of the importance of voluntary mobility, as demonstrated by meaningful community participation in relocation schemes. As a community-led response to climate risk, voluntary immobility likewise centers on the agency of affected populations, and is often associated with strong attachments to place. The alternative to voluntary mobility and voluntary immobility—namely, forced relocation—has been found in other contexts to have negative impacts on affected groups.

Climate Adaptation Strategies in the Pacific Islands

In the Pacific Islands, saltwater intrusion and coastal erosion associated with climate change are beginning to make some areas uninhabitable. This trend has forced the difficult question of whether to relocate some households or entire villages to protect infrastructure and livelihoods where in-situ adaptation is insufficient. Few specific instances of planned climate-related relocation have yet occurred, although other kinds of relocations have taken place throughout the history of the region. Some were imposed by colonial authorities, for example, to ease problems associated with remoteness from central authorities. In other cases, relocations became necessary following nuclear testing or mining.

Development-forced displacement and relocation, common throughout the world in recent history, provide important lessons for climate-change retreat. When populations must relocate to make way for dams, hydroelectricity projects, or urban expansion, the outcomes are often negative and typically include loss of land and employment, reduced access to common resources, economic marginalization, health issues, food insecurity, and cultural impacts. Similar risks are likely when the effects of climate change raise the prospect of unwanted relocation.

However, positive outcomes can result from relocation—whether development or climate-change-related—if communities themselves lead or are equal partners in the decision-making and implementation process. This is particularly true when the relocated community has an existing governance structure in place, for example, a village council. When national government planners present a village with an identified risk of becoming uninhabitable from climate impacts, the village council can use existing and likely trusted mechanisms to organize meetings between community members and national officials; deliberate on the issues according to cultural protocols; make decisions that represent the community’s concerns; and thus contribute meaningfully to their future with the assistance of government planning processes.

Voluntary Relocation

In the Pacific Islands, several nonclimate-related voluntary relocations have occurred in the past. An example is the purchase of Kioa Island in Fiji by the Vaitupu Island community of Tuvalu, a low-lying atoll state. Vaitupu partially relocated its residents to Kioa in the 1940s while still under British colonial rule. Less voluntary was the relocation of the Banaban islanders in Kiribati to Rabi Island, also in Fiji, following the decimation of Banaba by colonial phosphate mining around the same time. Not surprisingly, the legacy of the Kioa voluntary relocation has been more positive.

Figure 1. Map of the Pacific Islands

Source: OpenStreetMap Contributors, “OpenStreetMap,” accessed June 1, 2018, available online.

Today, though the Vaitupuan population on Kioa is formally part of Fiji, it is culturally and economically resilient due to strong links to the remaining community on Vaitupu Island. Notably, the Vaitupuans are considering Kioa for further relocation if climate change impacts on their island worsen. The Tuvaluan government, however, does not appear to strongly support this idea, being focused on solutions that are equitable for all Tuvaluans. Meanwhile, the Banabans in Fiji have retained their culture but continue to face emotional upheaval associated with the destruction of their homeland.

Other Pacific Island governments are developing a range of different kinds of plans for climate-related retreat, including international migration and relocation schemes. The most well-known of these is the Migration with Dignity policy in Kiribati, a low-lying state extremely vulnerable to climate impacts. The policy facilitates permanent and temporary labor migration on a voluntary basis as a long-term adaptation measure. It aims to nurture the small international i-Kiribati diaspora, ultimately supporting voluntary retreat through strong international social networks.

In Fiji, unlike Tuvalu and Kiribati, internal relocation to higher ground is often feasible. The Fijian government has identified several dozen vulnerable coastal villages and is beginning to assist with local relocation of communities that have agreed to move, by facilitating movement of dwellings and other infrastructure to less vulnerable areas within the village’s traditional lands.

Further, the Fijian government takes a community-consultation approach to retreat decision-making. Villages in Fiji have the opportunity to voice their needs to the national government and make the ultimate decision on relocation. The government encourages a strong sense of involvement and ownership in climate-change planning by communities, many of which follow tradition in making decisions at the village level.

When Communities Choose to Stay

It is important to note that most vulnerable coastal communities in the Pacific Islands currently prefer not to migrate or relocate, at least in the near term, regarding any form of retreat as the least-preferred adaptation option. Instead, communities and national governments are prioritizing on-site accommodation and protection adaptation measures; these include building sea walls, improving drainage, and planting mangroves.

Across the Pacific, land is crucial to indigenous worldviews and identities. The Fijian notion of vanua, for example, refers to the identity of a community and its place; vanua is a spiritual and cultural concept that nourishes indigenous Fijian life itself. Moving away from the land, therefore, causes enormous upheaval in cultural and spiritual life as well as economic and practical concerns such as loss of infrastructure. The land is where ancestors are remembered and where foundation myths take place.

Policies to Support the Voluntarily Immobile

Reflecting the cultural significance of land to these communities, Pacific Island climate-response plans include provisions to support those who choose not to leave. Kiribati’s Migration with Dignity policy allows individuals and families to each decide against migration, while leaving open the possibility of moving in the future.

National policy in Tuvalu expressly posits relocation as the last resort. Existing migration schemes for Tuvaluan citizens, such as the Pacific Access Category for quota-based, age-specific labor migration to New Zealand, are available to individuals or families who choose migration, but there is no national approach to collective retreat as in Kiribati. Both Tuvalu and Kiribati prioritize in-situ adaptation rather than any type of retreat.

Fiji’s national government is pioneering policy development to provide equal support to all its coastal communities, whether they choose to stay or relocate. Draft guidelines include procedures for working with communities that choose immobility, with an eye to maintaining human rights and dignity. The guidelines recognize that sensitive ongoing dialogue and emotional and legal support may be needed, to be facilitated by the Fijian government. This is particularly important if and when adaptation options on site are deemed to have been exhausted by planners. Fiji’s draft guidelines also support forced relocation if human life is in immediate danger.

When communities choose to remain in areas heavily impacted by climate change, the government could sensitively encourage them to nevertheless explore long-term, gradual, and diversified relocation options for younger generations. For instance, a village might decide to build new housing in safer areas while subsistence agriculture, community meeting areas, burial grounds, and other culturally important landmarks remain in their original sites, as is being discussed in several villages in Fiji. There may also be a need for a community’s culture and identity to be expressed and documented in community-led filmmaking, storytelling, school curricula, or social media, to support intergenerational cultural resilience at a time of profound change.

International Response

The international community has supported in-situ adaptation through extensive climate adaptation projects, aligning with the desire of many communities to stay in place. The 2016 Paris Climate Agreement and subsequent multilateral climate talks—including the UN’s COP 23 in November 2017, presided over by Fiji—have showcased the concerns of local and indigenous communities and highlighted the need for adaptation. Since 2010 the Adaptation Fund, heavily financed by European governments, has committed US $476 million to climate adaptation and resilience projects in 74 countries around the world, and in 2017 the fund broke its single-year fundraising record.

However, assuming that community members will relocate when external “experts” deem in-situ adaptation to be exhausted is problematic, given it is already clear that communities may not agree. If individuals and communities do assert a right to stay on land deemed by officials to be uninhabitable, arguably a new principle of climate justice that assures their dignity, and their right to stay, is needed at the international level.

On the other hand, while countries less vulnerable to the effects of climate change advance new, climate-specific migration avenues, such as New Zealand’s proposed climate visa, such channels may only be successful from the perspective of migrants themselves if they allow for circular mobility: back-and-forth movement between a new place of residence and the cultural homeland. Since their relocation to Kioa, Vaitupuans have engaged in some circular migration between the two islands, for example. The right to return home periodically to visit ancestral burial places and other important sites, and thereby nourish cultural and spiritual resilience, may be the key ingredient missing in current climate migration policy debates. The notion of the “climate refugee” fleeing a damaged place strongly suggests a one-off, one-way movement, a culturally insensitive approach that does not take account of deeply held attachments to place. Equitable forms of financial support for periodic visits home should be considered in climate mobility policies.

Including the Immobile in Climate Discussions

National governments and humanitarian organizations concerned with climate migration arguably have an obligation to support the decisions made by individual communities to retreat or remain, in ways that empathize with issues of cultural loss and enshrine ethics and human dignity. Policymakers would do well to better understand voluntary immobility and its significant political and cultural implications for vulnerable groups.

Pacific activist groups such as the Pacific Climate Warriors frequently highlight the importance of their land, ancestral homes, culture, and identity in their campaigns for global greenhouse gas emission reductions. Yet reductions are not happening fast enough to mitigate climate change, and so the difficult choice to stay in the face of tremendous risk becomes a powerful political statement about the strength and resilience of Pacific communities.

Both Kiribati and Tuvalu are significant in that the entire territories of both countries will likely be submerged due to rising sea levels, hence residents may eventually have no choice other than to migrate. In the meantime, however, most are choosing to stay. Further research and new ethical, legal, and policy frameworks are thus needed to support not only infrastructural and livelihood adaptation, but the cultural and spiritual challenges and opportunities that voluntary immobility presents.

The coming decade will likely witness more communities making collective and informed decisions about their future in a changing climate. Choosing to prioritize ancestral ties to place, collective identity, and religion is arguably a political as well as a cultural act. Voluntary immobility is one way for communities to themselves address the climate injustice that manifests when those least responsible for climate change face some of the most serious impacts. It is also a means for communities to push back against sensationalist visions of “climate refugees,” and reclaim their voice and agency in a future where climate change is all but inevitable.

Sources

Betts, Alexander and Angela Pilath. 2017. The Politics of Causal Claims: The Case of Environmental Migration. Journal of International Relations and Development 20 (4): 782–804.

Campbell, John. 2010. Climate-Induced Community Relocation in the Pacific: The Meaning and Importance of Land. In Climate Change and Displacement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Jane McAdam. Oxford, UK: Hart Publishing.

Charan, Dhrishna, Manpreet Kaur, and Priyatma Singh. 2017. Customary Land and Climate Change Induced Relocation—a Case Study of Vunidogoloa Village, Vanua Levu, Fiji. In Climate Change Adaptation in Pacific Countries: Fostering Resilience and Improving the Quality of Life, ed. Walter Leal Filho. Hamburg, Germany: Springer International Publishing.

Hall, Nina. 2017. Six Things New Zealand’s New Government Needs to Do to Make Climate Refugee Visas Work. The Conversation, November 29, 2017. Available online.

Kaufman, Alexander C. 2017. Climate Change Could Threaten up to 2 Billion Refugees by 2100. Huffington Post, June 26, 2017. Available online.

Koslov, Liz. 2016. The Case for Retreat. Public Culture 28 (2): 359-87.

Malologa, Faatasi. 2014. Climate Displacement in Tuvalu. In Land Solutions for Climate Displacement, ed. Scott Leckie. New York: Routledge.

McAdam, Jane. 2013. Relocation Across Borders: A Prescient Warning in the Pacific. Brookings Institution column, March 15, 2013. Available online.

Newland, Kathleen. 2011. Climate Change and Migration Dynamics. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Nolet, Emilie. 2018. A Tsunami from the Mountains: Interpreting the Nadi Floods in Fiji. In Pacific Climate Cultures: Living Climate Change in Oceania, eds. Tony Crook and Peter Rudiak-Gould. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Teaiwa, Katerina. 2005. Our Sea of Phosphate: The Diaspora of Ocean Island. In Indigenous Diasporas and Dislocations: Unsettling Western Fixations, eds. Graham Harvey and Charles D. Thompson, Jr. London: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2018. UN Climate Change Annual Report 2017. Bonn, Germany: UNFCCC. Available online.

Wilmsen, Brooke and Michael Webber. 2015. What Can We Learn from the Practice of Development-Forced Displacement and Resettlement for Organised Resettlements in Response to Climate Change? Geoforum 58: 76-85.