You are here

Sweden: By Turns Welcoming and Restrictive in its Immigration Policy

Immigrants in Stockholm, Sweden. (Photo: Mariano Mantel)

In 2015 a record-breaking 162,877 asylum seekers entered Sweden, which along with Germany was the preferred destination for a wave of Syrians, Afghans, and others who reached European soil in search of protection and better lives. In response, the Swedish government introduced border controls, followed in mid-2016 by a highly restrictive asylum and reunification law—a major policy shift for a country that has long prided itself on its generous asylum stance. Even as asylum applications and grants plummeted, concerns over immigration grew among the Swedish public. The nationalist, anti-immigration Sweden Democrats received 17.6 percent of the vote in September 2018 elections, while the center-left Social Democrats, in power for much of the 20th century, posted their worst results since 1908. Three months after an election that gave neither the center-left or center-right a majority, the country still struggled to form a government.

While Swedish asylum policy has undoubtedly taken a restrictionist turn, with the center-right coalition adopting the terms of the Sweden Democrats, other aspects of the country’s migration policy remain welcoming. Labor immigration has increased since a major reform was passed in 2008. Family reunification numbers have kept growing. And Swedish integration policy remains among the most liberal in the world, although it too has recently moved in a restrictionist direction.

The changes to Swedish asylum law since 2015 are dramatic, to be sure, but they have a historical context and are part of a complex set of migration policies. This country profile begins with an overview of historical and contemporary migration trends and debates, and then discusses two of the most vital migration policy areas today: asylum policy following the refugee crisis of 2015-16, and labor immigration policy post-2008 reform. In doing so, this article shows that Sweden has had a complicated and by turns welcoming and restrictive attitude to immigration—a historical dynamic that continues to shape Swedish migration policy.

Becoming a Country of Immigration

Migration is inextricably intertwined with the development of the Swedish state and society. Swedish kings during the Middle Ages and the early modern period expanded their administrative and territorial power by bringing in administrators, merchants, and soldiers from today’s northern Germany. One Swedish chronicle from the Middle Ages even complained of the outsized influence of these “foreign men” in Swedish politics.

As Sweden became one of the great European powers during the 17th and early 18th centuries—conquering Danish territory in present-day southern Sweden, Finland, and parts of northern Germany—it also became a leader in pre-industrial iron ore mining with the help of recruited Walloons, French-speaking iron workers and financiers from today’s Belgium. The unmatched iron refinery skills of these workers together contributed to Sweden becoming a leading exporter of canons during the 17th century.

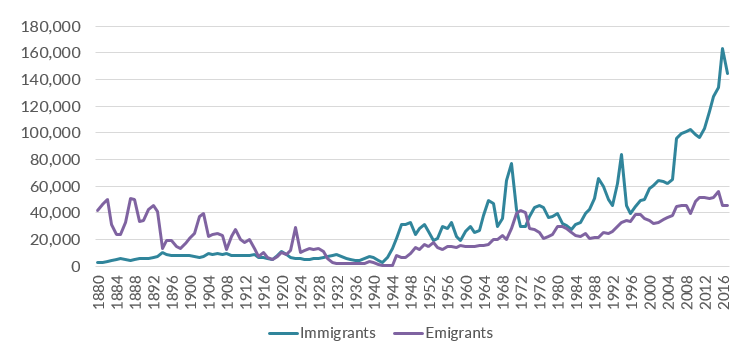

From 1800 to 1850 Sweden saw two major changes that set the terms for its migration dynamic for the coming 80 years: a significant population increase on the one hand, and major famines resulting from a series of devastating crop failures on the other. These changes turned Sweden into a country of emigration. Between 1850 and 1930 more than 1 million Swedes made their way to the United States. Several hundred thousand also migrated to other European countries, among which Denmark was the top receiving destination.

Sweden became a country of net immigration in the 1930s despite passage of the restrictive Aliens Act, the country’s first immigration law, in 1927. It remains the key piece of legislation for all aspects of migration, with modifications. The law’s two original aims were to protect the domestic labor force from foreign job competition and, heavily informed by theories of race and eugenics, to “control immigration of peoples that do not to our benefit allow themselves to meld with our population.” Such racialized language was later dropped, but a contradictory attitude toward immigration has been a mainstay in Swedish responses to immigrants and immigration.

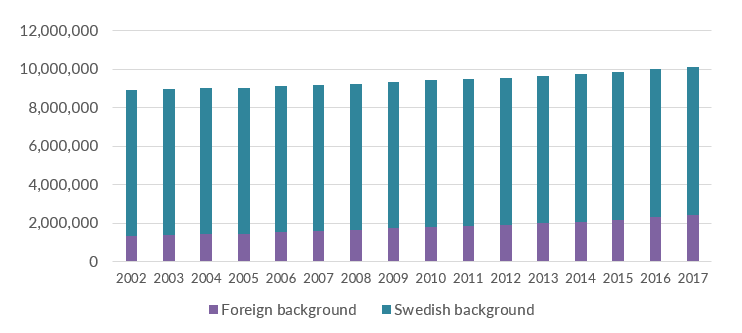

Today, the foreign born represent 18.5 percent of Sweden’s 10 million residents.

Figure 1. Swedish Immigration and Emigration Flows, 1880-2017

Sources: Statistics Sweden, "Befolkningsutveckling 1749-2017,” accessed October 3, 2018. Available online.

The Guest Worker Era

Although Sweden never had an official guest-worker policy, the demand for labor immigrants grew with economic expansion following World War II. Between the 1950s and early 1970s the vast majority of immigrants were guest workers. The number of foreign born tripled during this time, from 198,000 to 538,000.

Most of these immigrants came from other Nordic countries, benefiting from the formation of the Common Nordic Labor Market in 1954 and the abolition of border controls within the Nordic area in 1957. By 1970 there were 191,000 Finnish immigrants in Sweden, by far the largest group. It was only when the labor demand of an expanding heavy industry outpaced the available Nordic immigrant supply in the 1950s and the 1960s that tens of thousands of guest workers were recruited from countries such as Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey, Hungary, Austria, and Italy.

The Swedish state saw guest workers as temporary migrants and assumed that they would eventually return home. This perception, combined with the decentralized nature of migration policymaking and management that existed until the 1980s, underlies Sweden’s haphazard immigration policy during this era. The Swedish Immigration Board (renamed the Swedish Migration Agency in 2000) was formed in 1969. But it took until the 1980s for all migration matters to be brought under its umbrella, as previously policy was directed by a number of state agencies together with the municipalities.

As Swedish economic expansion began to wind down in the late 1960s, the state and heavy industry sector saw less need for immigrant labor. Consequently, in 1967 Sweden began to regulate non-Nordic labor immigration, seeking to curb the arrival of guest workers and encourage those already present to leave. The economic crisis of the early 1970s and its aftermath ended demand for foreign labor in heavy industry, bringing the era of labor immigration to a halt.

The state’s assumption that the guest workers would return home proved false. Not only did most stay on, but they also became citizens and began to apply for family reunification visas. Ironically, the restrictive 1967 law opened a new path to immigration in the form of family reunification, which meant that large numbers of people continued immigrating to Sweden.

The Family Reunification and Refugee Era

Family reunification has been one of the two largest immigrant categories since the 1970s, with numbers steadily increasing since then. In 2005, 22,713 people received residence permits through the family reunification path, a number that reached 48,046 in 2017.

The other category is that of refugee or other humanitarian category, such as subsidiary protection status. Sweden saw limited numbers of refugees during the labor immigration period, though it had taken in tens of thousands in the waning days and immediate aftermath of World War II. The admission of refugees in the 1950s and the 1960s followed a Cold War logic, according to which Sweden professed official neutrality but was in practice close to the Western bloc. Larger groups of refugees during this time made their way to Sweden following the Hungarian Uprising of 1956, the 1968 Prague Spring, and the Greek military coup of 1967.

Major political upheavals, wars, and interventions around the globe began creating the conditions for the record levels of displacement witnessed today. Sweden became a major receiving country of both asylum seekers and resettled refugees in the late 1970s and 1980s. It is during this time, which coincided with the rise of multiculturalism, that Sweden became known as a humanitarian haven, embracing people fleeing persecution from both Cold War blocs.

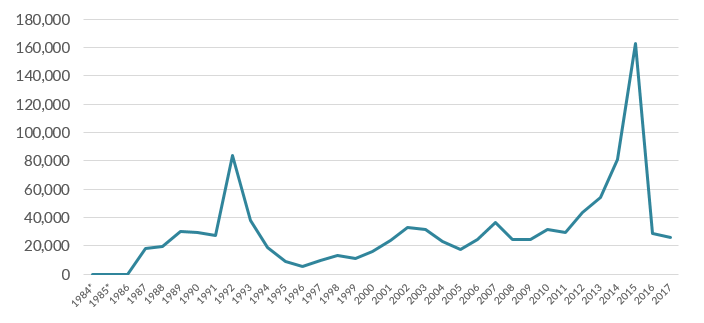

Figure 2. First-Time Asylum Applications Received by Year, 1984-2017

*These figures refer to first-time applications from 22 of Sweden's 118 police districts and correspond to approximately 90 percent of the total number of first-time applicants.

Source: Swedish Migration Agency, "Applications for asylum received," data for 1984-94, available online; data for 2000-2017, available online. Accessed October 3, 2018.

Increasing Diversity, Multiculturalism, and Welfare-State Integration

Since the 1970s, large numbers of immigrants have come from non-European countries, introducing into Swedish society different religions and ethnic backgrounds. More than 50 percent of the foreign born in Sweden between 1970 and 2016 originated elsewhere in Europe—chiefly other Nordic countries, former Yugoslavia successor states, Germany, and Poland. Finland was the single largest national category until 2010, making up 12 percent of all foreign born, slipping now to second place, narrowly trailing the former Yugoslav republics.

Currently, around 849,000 of all foreign born in Sweden come from Europe, while around 1 million have their origins in non-European regions, in particular the Middle East and Asia.

As Sweden began encountering immigrants from non-European regions, the higher employment rates immigrants recorded over native-born Swedes during the guest-worker era began falling beginning in the 1970s, with foreign-born unemployment rates eventually overtaking those of native-born Swedes. The unemployment rate in 2018 was four times higher among those with an immigrant background, which includes those born abroad as well as Swedes whose parents were born abroad.

Figure 3. Population in Sweden with Foreign or Swedish Background, 2002-17

Note: A person with a foreign background is defined as a person who is born abroad or born in Sweden to two parents who were born abroad. A person with a Swedish background is defined as a person born in Sweden to one or more parents born in Sweden.

Source: Statistics Sweden, "Utrikes födda samt födda i Sverige med en eller två utrikes födda föräldrar efter födelseland/ursprungsland, 31 december 2017, totalt,” accessed October 3, 2018, available online; Statistics Sweden, “Utrikes födda efter födelseland, ålder och år,” accessed October 3, 2018, available online.

There have been numerous shifts in Swedish integration policy, but also a continuity that differentiates Sweden from other European Union countries, which since the early 2000s have tied immigration rights to integration achievements. The twin goals of economic self-sufficiency and acculturation currently determine the acquisition of rights, benefits, and residency permits in most EU Member States. Although Sweden has introduced a few mandatory requirements since the 2000s, these have gone unenforced. Economic assistance and residence permits remain independent from integration performance. There is still a fairly broad political consensus that the acquisition of citizenship fosters integration, while the introduction of citizenship requirements stifles it.

The origins of Swedish integration policy lie in the late 1960s. The Swedish concept of a good citizen prevalent at the time assumed that by providing all citizens with fundamental social rights, they would feel that they belonged and would want to live up to certain expectations, above all the duty to work and contribute to full employment. This concept of welfare-state citizenship was extended to guest workers in 1968, when a law was passed that ensured that guest workers were covered by the same welfare provisions as Swedish citizens. Until the refugee and migration crisis of 2015-16, Sweden did not deviate substantively from this welfare state idea of integration.

Separately, Sweden in 1975 became one of the first countries to officially adopt a policy of multiculturalism, embracing ethnic and religious diversity and state support to safeguard minorities’ identity and culture. The state thus provided financial support for a range of activities, including state-funded minority cultural associations and mother-tongue instruction in primary schools.

This policy lasted until measures were introduced in 1986 that moved Swedish integration policy away from targeting groups and toward individuals. In 1997 Sweden introduced a new integration policy according to which individual integration needs, such as employment, would be targeted.

Although Swedish integration policy has fared well compared to other EU countries, the country nonetheless faces persistent integration problems. Geographical and social segregation is to blame for integration gaps, most observers and politicians agree. This segregation was the unintended result of a decade-long program beginning in 1965 to create 1 million new housing units in the perimeter of big cities, including Malmö, Stockholm, and Gothenburg.

These suburbs today exhibit very high youth unemployment, lower student achievement, and higher crime rates than in areas with a minority immigrant population, as well as general isolation from majority Swedish society and institutions. Such a social milieu has bred distrust toward institutions, not least the police, together with a sense of frustration. In 2013, car burnings and clashes with the police erupted in a number of migrant-dense suburbs.

Tensions over Religion

Another major issue in recent debates on integration is the spread of violent Islamism among Swedish Muslims, not least the 200-plus Swedes who decided to fight for the Islamic State in Syria and the Levant (ISIS). Linked to this issue is a widespread worry that there are Muslim organizations in Sweden that reject Swedish laws, customs, and values. Much of this discussion is highly politicized, but it also includes nuanced voices who recognize that some highly conservative mosques in Sweden do preach radical Islamism. The Swedish Muslim Council, the main umbrella organization for Muslim associations and mosques in Sweden, has repeatedly condemned Islamist terrorist attacks, and emphasized the importance of legal and social integration into Swedish society.

At the same time, hate crimes against immigrants—in particular young men from non-European Muslim countries—have increased. Reports of hate crimes based on Islamophobia, for example, grew from 278 in 2011 to 439 in 2016. Discrimination based on religion and ethnicity remains a significant social problem in labor recruitment.

In 2018, the government presented a ten-year plan to combat the complex issue of segregation, clothed in language that gestures toward integration policies found in other EU countries. The plan singles out five priority areas: housing, education, the labor market, democracy and civil society, and crime. Among the initiatives are a fast track for newly arrived immigrants to enter the labor market and become self-sufficient, and a call for civil-society organizations to help immigrants learn about democracy and the importance of voting. The plan earmarks 2.2. billion Swedish Krona (US $338 million) per year for various institutions and organizations at the national, county, and municipal level.

This plan is linked to an additional 7.1 billion Krona ($786 million) increase to the police budget for 2018-20. A political consensus has emerged in recent years that gang-related crime and violence, symbolized by the high murder rate in Malmö, has become a danger to public safety. Gangs whose members are often foreign born, are perceived to be the main cause of the violence.

The 2015-16 Migration and Refugee Crisis

Per capita, Sweden received the most asylum seekers globally in 2015. Beyond accepting refugees via its longstanding resettlement program, Sweden has taken in rising numbers of asylum seekers since 2012, exceeding 40,000 per year. Most of these recent arrivals have been Syrians, Afghans, and Iraqis. Other large groups include Iranians, Somalis, and Eritreans.

In public discourse, 2015 quickly became known as the refugee crisis. It led to a number of dramatic shifts in Swedish immigration law and policy, which culminated in the temporary asylum and family reunification law of 2016 (discussed below). But this restrictionist turn is not without precedent.

The Lucia Decision of 1989

Economic downturns starting in the 1970s had a long-lasting negative effect on employment rates. These downturns coincided with the rise of anti-immigrant, far-right parties, and with an increase in asylum seekers following the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. The 1980s and 1990s saw the rise of restrictive laws, policies, anti-immigrant parties, and xenophobia. Many of the current restrictive measures were either voiced, suggested, or enacted in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Among these, the Lucia Decision of December 13, 1989 stands out.

On this date, the Social-Democratic government, with support from the conservative Moderate Party and the Christian Democrats, announced that only those asylum seekers who met Geneva Convention criteria would be granted protection. The decision was made after the entry of 29,000 asylum seekers, including 5,000 Bulgarian Turks, in fall 1989. The government feared that accepting the latter group, who were not deemed Convention refugees but may nonetheless have had other grounds for protection, would signal an open invitation to the remaining 500,000 ethnic Turks in Bulgaria. Then, as in 2015, government officials deemed the situation an existential threat to the Swedish welfare state and a policy of regulated migration.

Yet the same Moderate Party that allowed the Lucia Decision to pass in 1989 tore it up in 1991 upon winning the election and forming a new government. This election also saw an anti-immigrant party, New Democracy (Ny Demokrati), enter Parliament for the first time. The reversal of the Lucia Decision, along with new Prime Minister Carl Bildt’s strong engagement in the Bosnian War, paved the way for the entry of refugees from the former Yugoslavia.

Even as Sweden welcomed a record-breaking number of asylum seekers—84,018 in 1992 alone and more than 200,000 between 1989 and 1993—it began suggesting the introduction of temporary protection status, a focus on aid and development in countries of first asylum, and voluntary return schemes in exchange for financial support. The entry of large numbers of refugees from the Bosnian war sparked cries of crisis by some, and voices in and out of government questioned whether the Swedish welfare state could bear the burden of so many refugees.

The 2016 Temporary Asylum and Family Reunification Law

The 2016 law, then, must be seen in light of policy development and debates that harken back to the 1980s. The temporary asylum law limits opportunities for asylum seekers and their family members to be granted permanent residence permits. There are now four protection categories: Convention refugee; subsidiary protection status; “other, for example, temporary residence permits due to impediment to enforcement;” and particularly distressing circumstances.

Under the law, Convention refugees are offered protection for three years, while subsidiary protection status is granted for 13 months. Both statuses can be extended. Subsidiary protection status, Convention refugee, and impediment to enforcement have predominated. In 2016, 47,219 people were granted asylum under the subsidiary protection category, while 16,872 were granted as Convention refugees. In 2017, 10,474 were granted subsidiary protection, while 838 were granted temporary protection due to impediment to enforcement. And from January to September 2018, 4,126 were granted Convention refugee status and 2,578 subsidiary protection status.

A condition for permanent residence under the new law is demonstrated economic self-sufficiency. The law also places a requirement of economic self-sufficiency on petitioners for family reunification.

Apart from changes to protection status acquisition, the new law has restricted asylum seekers’ rights to social and economic provisions. Since 2016, access to benefits such as free housing and a daily allowance have been eliminated for failed asylum seekers or those who have received an expulsion order, as well as those who have ignored the deadline for voluntary return.

The temporary law is meant to remain in force for three years, though the government has signaled that it will not make changes until there is satisfactory reform of the EU asylum system. Taken together, the changes introduced in the temporary law mark an unprecedented move toward tying immigration rights to integration achievements.

By September 2018, the Swedish Migration Agency was again able to process and decide on asylum applications in a timely manner. But as late as January 2017, 50,595 asylum seekers were still awaiting a decision, while 40,492 applications had not even begun to be processed. The delays in 2017 were especially important for unaccompanied minors. The status of unaccompanied minors nearly caused a crisis between the governing Green and Social Democrats parties. Rebelling against the Social Democrats’ hard line on unaccompanied minors, the Green Party reached a deal permitting about 9,000 minors to obtain permanent residency if they meet certain criteria. The provision’s legality has been contested and some migration courts have refused to apply it.

The new law has not affected the refugee resettlement program. In 2017, Sweden accepted 3,400 quota refugees, and in 2018 raised the number to 5,000. Thus far, quota refugees have not been politicized to the extent that asylum seekers have. However, following the lead of far-right parties in Denmark, the Sweden Democrats have called for abolition of the resettlement program.

Immigration detention and expulsions have increased since the refugee crisis began in 2015, as has time spent in detention. A total of 3,959 persons were detained in 2015, with an average stay of 20.7 days. By 2017, 4,379 were detained for an average of 31.5 days. In January 2016, Interior Minister Anders Ygeman called for the deportation of 80,000 rejected asylum seekers. Although Sweden is far from reaching that goal, returns have increased: 2,448 rejected asylum seekers were removed in the first eight months of 2018.

A New Labor Immigration Era

In the early 2000s, the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise began aggressively arguing that Swedish labor immigration legislation was old, rigid, and inefficient, in urgent need of replacement with a flexible system. Invoking a new reality of structural changes to the economy and an aging population, the business-oriented, center-right coalition government that came to power in 2006 identified the expansion of labor immigration from non-EU countries as a key priority.

Upon taking office, the coalition government introduced a legal distinction between temporary and permanent labor migrants, where workers in the former category would be tied to a specific employer and profession for two years. The government argued that hiring in the latter category would help Swedish employers address major recruitment problems. This change marks a clear departure from the first guest-worker era, during which workers were tied to their profession for one year but allowed to change employers.

In 2008 Sweden entered what may be called a new labor immigration era. In an unlikely alliance with the Green Party, the government significantly overhauled labor migration regulations to encourage companies to hire more workers, low-skilled and high-skilled alike, from outside the European Union. (See Table 1.)

The nature of this new era of immigration differs significantly from the guest-worker era. The first major difference lies in the changed power dynamic between unions, the state, and employers. In short, the Swedish corporatist model in which unions have had significant influence over labor policy has been eroded. During the earlier era, guest workers had to be unionized by law, because it ensured that their working conditions were equal to those of their Swedish fellow workers. The unions began seeing their power over immigration labor policy erode following Sweden’s entry into the European Economic Area in 1994, its EU accession the following year, and especially EU expansion in 2004 that made it possible for Eastern European workers to freely move to and work in Sweden without having to belong to a union.

A second key difference lies in the type of temporary workers most desired: in the 1950s and the 1960s, heavy industry drove demand, while currently, the IT and service sectors predominate. A third, and final, difference lies in policymakers’ preference after 2008 that immigrant laborers not only be offered but encouraged to obtain permanent residency.

Following the enactment of the 2008 law, labor immigration from non-European countries has increased significantly. Thailand, India, and China are the three largest sending countries.

Table 1. Work Permits Granted for Top 15 Countries of Citizenship, 2008-14

Note: Countries are sorted from largest to smallest based on 2014 totals.

Source: Swedish Migration Agency, "Uppehållstillstånd av arbetsmarknadsskäl 2000–2014,” accessed October 3, 2018, available online.

In 2017, of the 15,552 work permits granted, 4,029 were for IT workers; 3,043 for berry pickers or similar crops; 1,082 for civil engineers; 849 for chefs; and 781 for fast-food personnel.

The left-wing bloc that formed a minority government in 2014 did not renege on the 2008 reform. However, after widespread reports of exploitation of immigrant workers, the new government introduced regulatory measures, including recalling work permits if these workers’ salaries were found to be lower than those established through collective union bargaining.

Issues on the Horizon

The migration and refugee crisis that hit Europe in 2015-16 has left a deep mark on Swedish politics and society, and its impact is likely to grow. Two issues in particular merit close attention: a new parliamentary reality where the Sweden Democrats must be considered by the other political parties, and the impact of irregular forced migration on EU harmonization with regard to asylum policy.

Immigration scored as one of the top issues in the 2014 and 2018 Swedish elections. The Sweden Democrats, who first joined Parliament in 2010, received more than 13 percent of the national vote in 2014, making it the third-largest political party. It improved on that performance in 2018, its 17.6 percent national share exceeded in some counties and municipalities. It has become impossible for either of the two traditional blocs to form majority governments, since neither bloc wants to govern with the support of the Sweden Democrats. This new situation may prompt a structural change to Swedish parliamentarianism. Predictably, Prime Minister Stefan Löfven lost the parliamentary vote of confidence following the 2018 elections. However, with no contender able to garner enough votes to become the new Prime Minister outright, a caretaker government was still in place at this writing, with the various parties struggling three months after the election to establish a ruling coalition that would not require support of the Sweden Democrats.

In or out of government, the Sweden Democrats party has already pushed the major parties to adopt far-right rhetoric, increasingly associating asylum seekers with national-security threats, terrorism, and crime. Such rhetoric in turn has led to calls to further tighten border controls and increase Sweden’s ability to detain and deport asylum seekers. The electoral gains of the Sweden Democrats have led to the normalization of far-right migration discourse and a restrictionist convergence on immigration issues, including the temporary law of 2016, which received broad cross-bloc support.

EU asylum policy was tested during the 2015-16 crisis, and arguably failed. The Schengen Area, the Dublin Regulation, the burden-sharing system introduced to equitably distribute asylum seekers between Member States—none of these treaties and regulations were consistently applied. Instead, nation-state interests prevailed. Countries such as Greece, Italy, Poland, and Hungary blatantly disregarded EU treaties and regulations. This meant that a few countries—Germany, Sweden, and Austria—found themselves taking in most of the more than 1 million asylum seekers who made their way to Europe in 2015. In response this latter group of countries closed their borders and introduced restrictive legislation.

Sweden has announced that it will change its current legislation only once a working common EU asylum policy is in place. Such reform has not been forthcoming, and it is unclear whether it ever will, amid deep divisions between the southern states that initially receive the migrants, the eastern states that would preferably like to close the door for asylum seekers entirely, and the northern states where asylum seekers are keen to go. If inaction prevails, the next step for Member States such as Sweden might very well be to ask themselves whether it makes sense to have an EU policy on these matters. The failure of European asylum policy may be the straw that breaks the camel’s back and leads to further disintegration in the European Union. It would be ironic, however, if Sweden were to see the disintegration of EU migration policy precisely at the time when it is moving closer to it.

Sources

Bech, Cochran Emily, Karin Borevi, and Per Mouritsen. 2017. A “Civic Turn” in Scandinavian Family Policies? Comparing Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Comparative Migration Studies 5 (7): 1-24.

Borevi, Karin. 2014. Multiculturalism and Welfare State Integration: Swedish Model Path Dependency. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 21 (6): 708-23.

Byström, Mikael and Pär Frohnert. 2017. Invandringens historia: Från “folkhemmet” till dagens Sverige. Stockholm: Delmi.

Bucken-Knapp, Gregg. 2009. Defending the Swedish Model: Social Democrats, Trade Unions, and Labour Migration Policy Reform. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Calleman, Catharina and Petra Herzfeld Olsson, eds. 2015. Arbetskraft från hela världen: Hur blev det med 2008 års reform? Stockholm: Delmi.

Dagens Juridik. 2016. Staten får tvinga kommuner att ta emot flyktingar - Riksdagen klubbade lagen. Dagens Juridik, January 28, 2016. Available online.

Equality Ombudsman. 2012. Forskningsöversikt om rekrytering i arbetslivet: Forskning som publicerats vid svenska universitet och högskolor sedan år 2000. Available online.

---. 2013. Forskning om utsatthet hos förmodade muslimer och islamofobi i Sverige: En översikt av forskning publicerad vid universitet och högskolor i Sverige sedan år 2003. Available online.

Frank, Denis. 2017. Förändringar i svensk arbetskraftsinvandringspolitik 1954-2014. Arbetsmarknad och Arbetsliv 23 (1): 64-81.

Government Offices of Sweden. 2018. Regeringens långsiktiga insatser mot segregation. June 26, 2018. Available online.

Horvatovic, Iva and Johan Juhlin. 2017. De är de svenska IS-krigarna. SVT Nyheter. June 14, 2017. Available online.

Johansson, Cecilia. 2005. Välkomna till Sverige? Svenska migrationspolitiska diskurser under 1900-talets andra hälft. Malmö: Bokbox förlag.

Lönnaeus, Olle. 2013. Segregation bakom upplopp. Sydsvenskan. May 22, 2016. Available online.

Nilsson, Åke. 2004. Efterkrigstidens invandring och utvandring. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden. Available online.

Skodo, Admir. 2017. How Immigration Detention Compares Around the World. The Conversation. April 19, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Swedish Immigration Is Not Out of Control – It’s Actually Getting More Restrictive. The Independent, March 4, 2017. Available online.

Statistics Sweden. N.d. Befolkning efter bakgrund. Accessed October 2, 2018. Available online.

Stern, Rebecca. 2008. Ny utlänningslag under lupp. Stockholm: Svenska Röda Korset. Available online.

Svanberg, Ingvar and Mattias Tydén. 2005. Tusen år av invandring: En kulturhistoria. Stockholm: Dialogos förlag.

Swedish Governmental Inquiries. 2004. Utlänningslagstiftningen i ett domstolsperspektiv. Stockholm: Swedish Government. Available online.

---. 2017. Att ta emot människor på flykt: Sverige hösten 2015. Stockholm: Swedish Government. Available online.

---. 2017. Arbetskraftsinvandring till Sverige – befolkningsutveckling, arbetsmarknad i förändring, internationell utblick. Stockholm: Swedish Government. Available online.

Swedish Migration Agency. 2017. Protection Status. Last updated October 9, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Annual Report. Stockholm: Swedish Migration Agency. Available online.

---. 2018. Sveriges flyktingkvot 2018. Stockholm: Swedish Migration Agency. Available online.

---. N.d. Statistics. Accessed August 10, 2018. Available online.

---. N.d. Översikter och statistik från tidigare år. Accessed August 10, 2018. Available online.

Swedish Ministry of Justice. 2005. Utlänningslag (2005:716). Stockholm: Ministry of Justice. Available online.

---. 2016. Lag (2016:752) om tillfälliga begränsningar av möjligheten att få uppehållstillstånd i Sverige. Stockholm: Ministry of Justice. Available online.

Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. Hatbrottsstatistik. Last updated September 5, 2018. Available online.