You are here

Crisis in the Courts: Is the Backlogged U.S. Immigration Court System at Its Breaking Point?

The immigration court system is an arm of the U.S. Department of Justice. (Photo: Ryan J. Reilly)

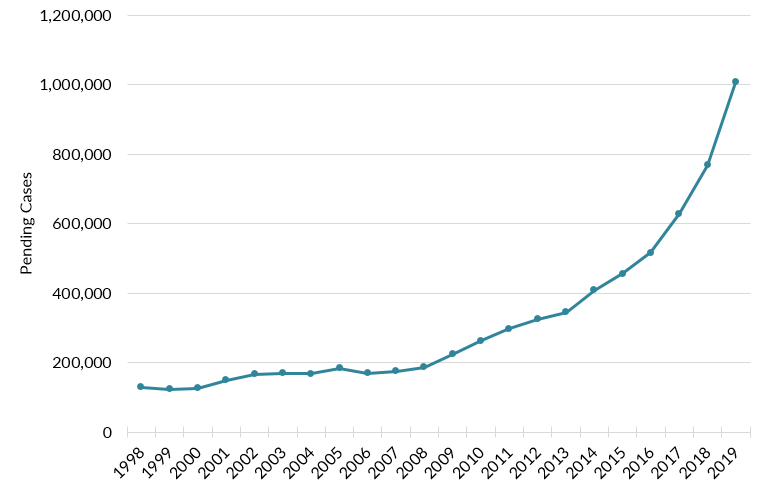

As major transformations to U.S. immigration policy and practice are advanced by the Trump administration at an unprecedented pace, one key yet little heralded part of the system has reached a breaking point: the immigration courts. With a backlog of slightly more than 1 million removal cases as of August 2019—a number that has quadrupled over the past decade—the courts have been unable to keep pace with enforcement and policy shifts funneling more noncitizens into the system and the changing nature of migration at the Southwest border.

Indeed, the number of unauthorized arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border in May 2019 marked the highest monthly total since March 2006, with nearly 133,000 apprehensions. Amid a major uptick in asylum seekers and other migrants from Central America, the country has witnessed a remarkable turnaround from 2017, when the lowest levels of illegal immigration were recorded since 1971, to rates not seen in more than a decade.

Limited in design and resources, the U.S. immigration court system is where many of the new arrivals’ cases will languish: wait times have skyrocketed in recent years, surpassing 700 days on average that a currently open case has been pending. A decision in immigration court can mean the difference between life and death for those fleeing violence and persecution. But the growing backlog and pushes to expedite decisions, combined with pre-existing disparities in asylum grant rates, could result in insufficient due process for those who need it most.

Based on analysis of data from the immigration court system, known as the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), as well as data obtained via Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University, this article explores the many challenges facing the U.S. immigration courts. It examines the overall backlog of cases and metrics including country of origin, funding levels for immigration enforcement agencies, and asylum grant disparities by court and representation status. It also examines the renewed campaign by immigration lawyers and other advocates to set the court system on a more independent course.

An Overtaxed System

In the United States, immigration courts are the federal government’s mechanism for judicial review of the cases of noncitizens it seeks to remove from the country. The system is made up of 63 courts spread across the country, both near and far from the border. The immigration courts, which are an arm of the Justice Department, are notably part of the executive branch, not the independent judiciary. As such, though EOIR was established to function as an independent body, it is subject to changing political motivations and priorities within the Justice Department.

Immigration judges, who may be attorneys coming to EOIR from other legal backgrounds such as military courts, decide deportation cases, all of which begin with a Notice to Appear (NTA) issued by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) summoning the immigrant to court. Because immigration court is a civil, not a criminal, proceeding, the government is not obligated to provide respondents with legal representation if the noncitizen cannot afford his or her own. For deportation proceedings initiated in fiscal year (FY) 2018, roughly 52 percent of noncitizens—including those with claims to asylum or some other form of relief and those without—had legal representation during their removal hearings.

The number of cases pending in immigration courts has more than quadrupled in the last decade, reaching a historic high of slightly more than 1 million as of the end of August 2019. At the time of writing, the backlog does not reflect all of the 330,000 administratively closed cases that former Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordered the judges to place back on the “pending” docket—meaning the true backlog has already surpassed 1.3 million cases.

The growth in the backlog can be attributed to a number of factors, including ramped-up immigration enforcement activities that were not matched with commensurate increases in court resources and the identification of rising numbers of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. interior. During the early 2000s, the backlog hovered between 100,000 and 200,000 cases, but this changed when the George W. Bush administration began ramping up interior immigration enforcement starting around 2006 (see Figure 1). The Obama administration then continued this heightened enforcement in its first few years through information-sharing programs with state and local law enforcement such as Secure Communities program and the Criminal Alien Program, alongside expanded use of the 287(g) program, which permits participating state and local law enforcement agencies to take part in federal immigration enforcement activities. These programs permitted U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to identify growing numbers of noncitizens for arrest and removal. This resulted in an uptick of unauthorized immigrants apprehended in the interior of the country, growing numbers of NTAs issued, and more cases added to the dockets of immigration courts.

Figure 1. Pending Cases in U.S. Immigration Courts, FY 1998-2019

Note: The pending court backlog as of August 2019 does not include the 330,000 administratively closed cases that former Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordered to be reopened and added to the active docket, meaning the total backlog exceeds 1.3 million cases.

Source: Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) data obtained by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University via Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, “Immigration Court Backlog Tool,” accessed September 29, 2019, available online.

Even after the Obama administration began narrowing its enforcement priorities in 2010-11 and again in 2014 to focus interior enforcement on the arrest and removal of serious criminals and security threats, recent arrivals, and those who had violated a prior removal order, immigration courts were confronted with a new challenge: a surge in the number of children and families arriving from Central America. In FY 2014, a then-record 69,000 unaccompanied children and 68,000 “family units” (the term used by U.S. Customs and Border Protection [CBP] to refer to a parent traveling with a child) arrived at the Southwest border, sending the government scrambling to process them.

Growing Central American Share

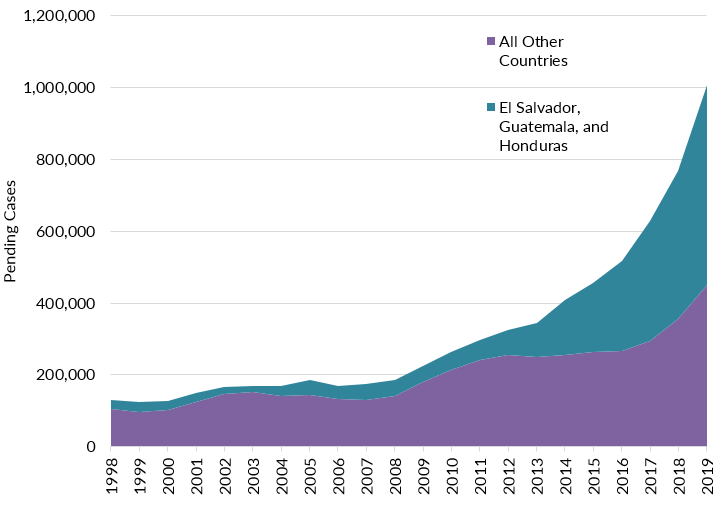

Prior to 2012, immigrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—the key sending countries in Central America—accounted for a relatively small share of cases in immigration court. This share grew from 21 percent in FY 2012 to 54 percent in FY 2019 (see Figure 2), as Central American immigration overtook arrivals from Mexico. A complex interplay of push and pull factors underlies the uptick in Central American migration. High rates of gang violence and domestic violence, as well as deep poverty exacerbated by drought and crop failure, and lack of economic opportunities, have plagued these countries and pushed people to head north at high rates. For child arrivals, the prospect of reuniting with a parent or other family member in the United States is often another key motivator.

Figure 2. Pending U.S. Immigration Court Cases by Country of Origin, FY 1998-2019

Source: TRAC, “Immigration Court Backlog Tool,” accessed September 29, 2019, available online.

In previous eras, border apprehensions were more often single male Mexican adults trying to surreptitiously cross the border in pursuit of economic opportunities. But today, the picture of who arrives at the border has changed. Central American families, children, and single adults—including many women—as well as immigrants from beyond Latin America now commonly turn themselves in to border agents in order to gain entry to the United States, some expressing a fear of returning to their countries.

Resources Fail to Keep Pace

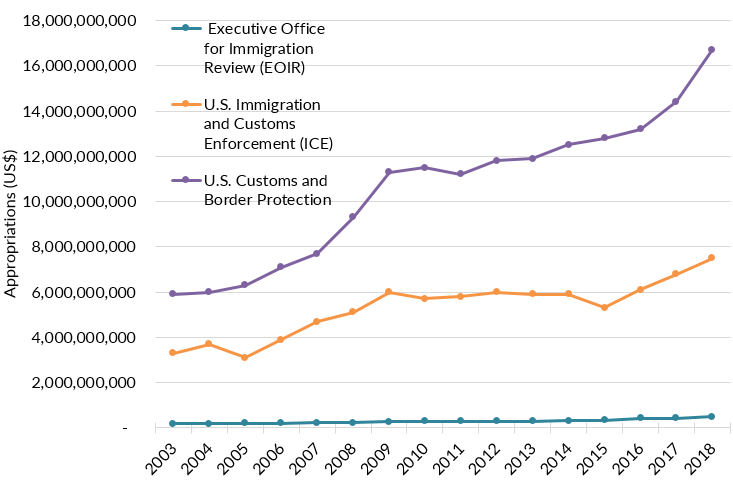

Experts and immigration judges have pointed to a lack of adequate resources as a major factor behind the growth of the backlog. The federal government spends far and away more money on carrying out apprehensions at the border and identifying noncitizens for arrest and removal in the interior than it does on the immigration courts. While funding for EOIR has increased slightly in recent years, it has been significantly outpaced by spending on the other levers of immigration enforcement.

To put funding streams in relief, Figure 3 compares appropriations for EOIR to appropriations for ICE and CBP—the two main immigration enforcement agencies—over the past decade. In 2018, Congress appropriated $16.7 billion for CBP and $7.5 billion for ICE, and just $437 million for immigration courts (though the latter number has increased from $238 million in 2008). While CBP and ICE carry out many functions besides immigration enforcement activities and their budgets should not be compared one-for-one to EOIR’s budget, this picture shows the stark contrast in resources between the agencies.

Figure 3. Appropriations by Immigration Enforcement Agency, FY 2008-18

Note: The budget data are rounded to the nearest $1 million for EOIR and the nearest $100 million for ICE and CBP.

Sources: EOIR budget data for FY 2003-18 from Justice Department, “Budget and Performance Summary,” various years, available online; and CBP and ICE data for FY 2003-18 from Department of Homeland Security, “Budget-in-Brief,” various years, available online.

Case Receipts Outnumber Case Completions

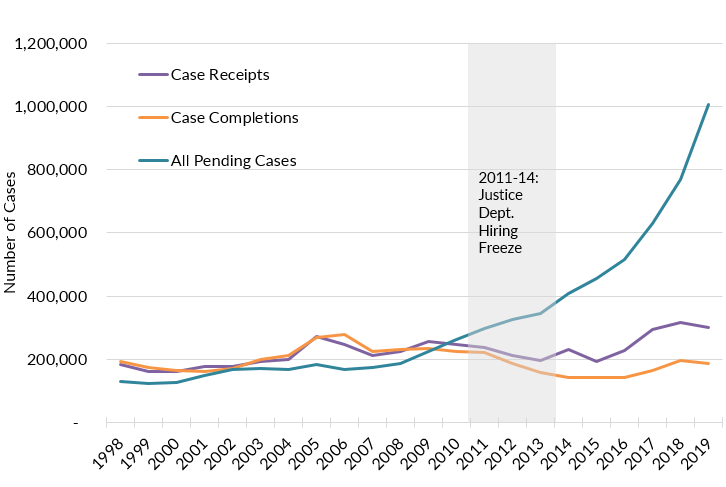

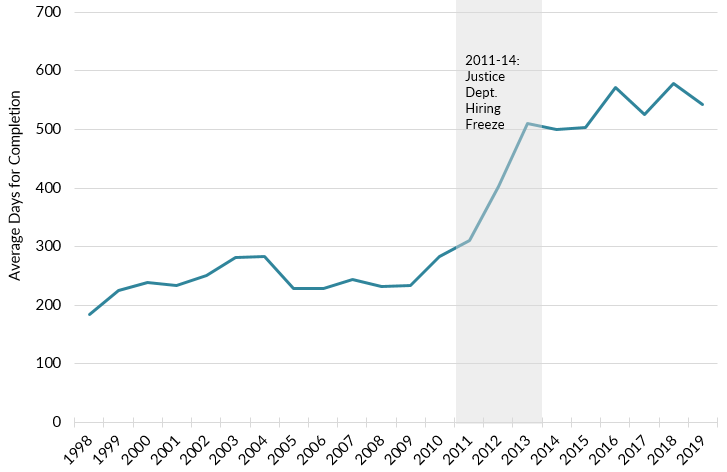

As a result of resource limitations, as well as a Justice Department hiring freeze during the sequester of 2011-14, the immigration courts system has not been able to keep up with the increased pressures placed on it. Even while Congress appropriated funds in 2017 to add additional judges and the Trump administration hired 47 judges in the first half of FY 2019, others have retired or otherwise left the bench—resulting in a much smaller net gain. About 39 percent of current immigration judges are eligible to retire, the Government Accountability Office reported in 2017. The same report found that since the hiring freeze ended, it has taken EOIR an average of 647 days to hire a new judge.

The mismatch in judges versus caseload has led to more cases left pending at the end of every year—and a surging backlog. Figure 4 compares case completions with new case receipts and total pending cases, showing that yearly completions actually took a dive from 2011-14, and only recently began to turn back up as EOIR has added more judges.

Figure 4. U.S. Immigration Court System Case Completions, New Case Receipts, and All Pending Cases, FY 1998-2018

Note: For case receipts and completions, 2019 data include through June; for pending cases, 2019 includes through August.

Source: EOIR, “Adjudication Statistics: New Cases and Total Completions,” through June 2019, accessed September 29, 2019, available online; and TRAC, “Immigration Court Backlog Tool,” accessed September 29, 2019, available online.

As the case completion rate has stagnated, the average time it takes to complete a case has ticked upward, more than doubling in the past decade (see Figure 5). Wait times for currently pending cases are even longer. In 2019, noncitizens on average had been waiting 705 days for their removal cases to be adjudicated—almost two years. Waits were even higher in the country’s most backlogged and resource-strapped courts: in San Antonio, the average respondent had waited 1,038 days, while in Arlington, Virginia the average wait was 973 days.

Figure 5. Average Days for Case Completion in U.S. Immigration Court System, FY 1998-2019

Source: TRAC, “Immigration Court Processing Time by Outcome,” accessed September 29, 2019, available online.

Disparities in Asylum Outcomes

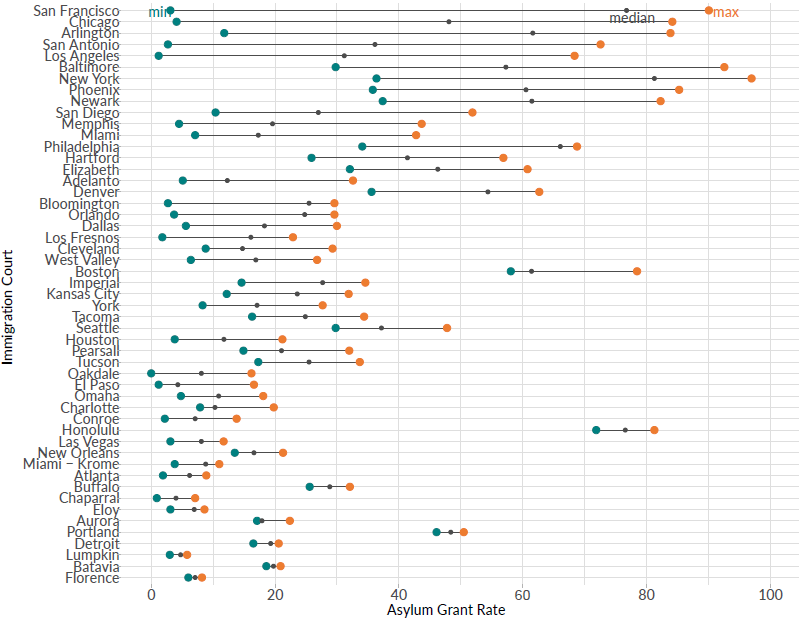

While asylum cases represent a fraction of the overall number of cases in the immigration court system, at about one-third of cases, available data show that disparities abound in terms of treatment of asylum claims by individual court. A person’s chance of being granted asylum can depend not only on the court he or she has been assigned to, but also the individual judge hearing the case. Even though cases are assigned randomly to judges within courts, grant rates at the judge level vary widely in some courts (see Figure 6). In a dataset that includes all asylum decisions from FY 2013-18, San Francisco had the highest asylum disparity by judge: the maximum grant rate in that court for any judge was 90 percent, while the lowest was just 3 percent—a range of 87 percentage points. Meanwhile, the median rate was 77 percent, suggesting that more judges are clustered around the higher end of the distribution. Courts in Chicago, Arlington, and San Antonio also had large disparities at the judge level. Notably, one judge in the Oakdale, Louisiana immigration court has never granted an asylum claim.

Figure 6. Asylum Grant Rate Ranges among Judges, by U.S. Immigration Court, FY 2013-18

Note: Courts are sorted in descending order by their grant rate range (maximum grant rate minus minimum rate). Three courts with only one judge in the dataset (Harlingen, New York Detention, and Otay Mesa) were excluded.

Source: TRAC, “Judge-by-Judge Asylum Decisions in Immigration Courts FY 2013-18,” accessed September 16, 2019, available online.

Impact of Legal Representation

In addition to location, legal representation—or lack thereof—is another factor that can weigh on the outcomes of removal cases. Because immigration court is a civil, not a criminal, proceeding, respondents in removal proceedings are not provided with legal counsel by the government. EOIR is required to give immigrants a list of pro bono legal services available in their area, but otherwise it is up to the immigrant to find a lawyer if desired.

Between 2007 and 2012, just 37 percent of all respondents and 14 percent of those in detention obtained representation, according to a national study by Ingrid Eagly and Steven Shafer. The study also found that the odds of being granted relief were 15 times higher for those with counsel than those without. Further, the involvement of representation was associated with greater efficiencies in court proceedings. Noncitizens are also more likely to attend their court hearings if they have representation. For proceedings beginning in FY 2008 to June 2019, 97 percent of immigrants with an attorney appeared, compared to 83 percent of the total, according to an analysis of TRAC data.

Representation can be a particularly crucial lifeline for unaccompanied child migrants in deportation proceedings. In the years since the uptick in unaccompanied child arrivals, many children, some toddlers, were issued NTAs and eventually appeared in immigration court, often alone, without legal counsel, and unaware of what was going on around them—a reality that continues today.

An analysis of representation rates and asylum grant rates by country of origin for FY 2012-17 shows a clear positive correlation between the two (see Figure 7). Countries such as China, Ethiopia, and Nepal have relatively high representation rates and asylum grant rates, while Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have lower rates for both.

Figure 7. Representation Rates and Asylum Approval Rates in U.S. Immigration Court by Country of Origin, FY 2012-17

Note: Nationalities with the 10 largest numbers of decisions in the data set are labeled.

Source: TRAC, “Table 2. Immigration Court Asylum Denial Rates by Nationality and Representation Status, FY 2012-17,” accessed September 15, 2019, available online.

Notably, this chart does not take into account the differences in the merits of cases and availability of evidence by country of origin, suggesting that even without holding these factors constant, representation has an outsized impact on asylum grants. As the backlog grows and judges are pressured to expedite case completion, disparities such as those by representation and judge hearing the case could weigh even more heavily on case outcomes. Further, in July 2019 the Trump administration began replacing in-person interpreters at initial court hearings with videos informing immigrants of their rights in various languages—an attempt at greater efficiency that could cause confusion and disadvantage immigrants without attorneys to answer any questions they may have.

An Unsustainable Path

The backlog in the immigration court system has spiraled rapidly upward over the past decade. Pressures from external forces (shifts in migration to the Southwest border and in immigration enforcement policy) as well as internal forces (changes in EOIR policies and case-management practices) amid generally stagnating resources have pushed the system to a breaking point. Recent decisions by the Trump administration have only exacerbated the workload. Noncitizens in immigration court feel the brunt of the backlog’s effects, such as increased wait times overall and “rocket docket” hearings for migrant families in ten courts.

Attorney General William Barr, and his predecessor, Sessions, have actively used their referral and review power to reshape the immigration court system, while a Trump administration executive order directed the attorney general to reassign immigration judges to detention facilities at the border, resulting in adjourned hearings and “docket churn” as priorities shifted and nondetained pending cases were pushed to the back burner. Further, they have set new precedents regarding who qualifies for asylum. In two notable decisions, Sessions substantially limited the cases in which migrants claiming fear of domestic or gang violence could qualify for asylum (Matter of A-B-), and allowed judges to summarily deny asylum claims without a full evidentiary hearing (Matter of E-F-H-L-). Meanwhile, the Justice Department has also introduced a quota system, requiring immigration judges to complete 700 cases per year, along with additional performance metrics, ramping up the pressure on judges even further.

Immigration judges have repeatedly spoken out against what they see as a push to make the courts move faster without balancing due process or providing the additional resources needed to bolster the system. Some have resigned in protest, expressing frustration about the additional pressures placed on them by the new policies. And in a move interpreted by some as an insult, by others as seeking to muzzle dissent, the Justice Department in August 2019 moved to decertify the immigration judges’ union—which has been outspoken in its criticism of the administration’s immigration policies. The Justice Department argues the move is appropriate, terming the judges “management officials.”

Experts have suggested several potential ways to work through the backlog and regain control over the system’s caseload without narrowing judges’ discretion, quotas, or similar measures. Four legal organizations—the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA), American Bar Association, Federal Bar Association, and the National Association of Immigration Judges—sent a letter to Congress recommending that it make the immigration court system an independent one, separate from the Justice Department, to ensure impartiality and safeguard the system from political manipulation. More than 1,000 immigration lawyers also signed onto an AILA letter to Sessions, urging him to support reform.

Regarding asylum cases, the Migration Policy Institute recommends empowering asylum officers with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service’s Asylum Division to fully decide credible-fear cases instead of referring them to immigration courts. Considering that asylum officers already make initial decisions in these cases, this would allow meritorious ones to be resolved more quickly while making more efficient use of the limited time and resources of the asylum office and immigration judges.

In terms of EOIR itself, experts point to the need for additional judges and support staff, both in the near term and longer term. While the Trump administration has been hiring more judges, this on its own has not been enough to work through the backlog. Finding ways to streamline the hiring process, continue attracting new judges while ensuring they have the tools needed to do their jobs, and make other administrative reforms will be important moving forward.

The immigration courts are key to the overall health and integrity of the broader U.S. immigration system, due to the role they play in adjudicating many asylum claims and removing noncitizens without a claim to stay in the country. With the court system reaching a breaking point, as the backlog surpasses more than 1 million pending cases, it will take thoughtful structural reforms to pull the immigration courts back from the brink. Meanwhile, the current reality will have implications for migrants, asylum seekers, and the attorneys and judges handling their cases for years to come.

Sources

American Immigration Council (AIC). 2019. Immigrants and Families Appear in Court. Washington, DC: AIC. Available online.

American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA). 2018. AILA Calls for Independent Immigration Courts. Washington, DC: AILA. Available online.

---. 2019. Legal Associations Call for Independent Immigration Court System. Letter to Congress, AILA, July 11, 2019. Available online.

Benner, Katie. 2018. Immigration Judges Express Fear that Sessions’ Policies Will Impede Their Work. The New York Times, June 12, 2018. Available online.

Department of Homeland Security. N.d. Budget-in-Brief. Budget data for FY 2003-18. Accessed September 29, 2019. Available online.

Eagly, Ingrid V. and Steven Shafer. 2015. A National Study of Access to Counsel in Immigration Court. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 164 (1). Available online.

Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). 2019. Adjudication Statistics: New Cases and Total Completions. Updated July 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Budget and Performance Summary. Budget data for FY 2003-18. Accessed September 29, 2019. Available online.

Goldbaum, Christina. 2019. Trump Administration Moves to Decertify Outspoken Immigration Judges’ Union. The New York Times, August 10, 2019. Available online.

Human Rights First. 2017. Tilted Justice: Backlogs Grow While Fairness Shrinks in U.S. Immigration Courts. New York: Human Rights First. Available online.

Johnson, Ben. 2018. We Need an Independent Immigration Court System. The Hill, October 1, 2018. Available online.

Kopan, Tal. 2019. Trump Administration Ending In-Person Interpreters at Immigrants’ First Hearings. San Francisco Chronicle, July 3, 2019. Available online.

Meissner, Doris, Donald M. Kerwin, Muzaffar Chishti, and Claire Bergeron. 2013. Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Meissner, Doris, Faye Hipsman, and T. Alexander Aleinikoff. 2018. The U.S. Asylum System in Crisis: Charting a Way Forward. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Meissner, Doris and Sarah Pierce. 2019. Policy Solutions to Address Crisis and Border Exist, But Require Will and Staying Power to Execute. Commentary, April 2019. Available online.

Miroff, Nick and Maria Sacchetti. 2019. Burgeoning Court Backlog of more than 850,000 Cases Undercuts Trump Immigration Agenda. The Washington Post, May 1, 2019. Available online.

Pierce, Sarah. 2018. Sessions: The Trump Administration’s Once-Indispensable Man on Immigration. Migration Information Source, November 8, 2018. Available online.

Preston, Julia. 2016. Deluged Immigration Courts, Where Cases Stall for Years, Begin to Buckle. The New York Times, December 1, 2016. Available online.

Rose, Joel. 2018. Justice Department Rolls Out Quotas for Immigration Judges. NPR, April 3, 2018. Available online.

Shear, Michael D., Miriam Jordan, and Manny Fernandez. 2019. The U.S. Immigration System May Have Reached a Breaking Point. The New York Times, April 10, 2019. Available online.

Shugall, Ilyce. 2019. Op-Ed: Why I Resigned as an Immigration Judge. The Los Angeles Times, August 4, 2019. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2019. Southwest Border Migration FY 2019. Updated April 24, 2019. Available online.

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2017. Immigration Courts: Actions Needed to Reduce Case Backlog and Address Long-Standing Management and Operational Challenges. Washington, DC: GAO. Available online.

Thompson, Gabriel. 2019. “Your Judge Is Your Destiny.” Topic Magazine, July 2019. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) Immigration. 2017. Table 2. Immigration Court Asylum Denial Rates by Nationality and Representation Status, FY 2012-17. Updated November 20, 2017. Available online.

---. 2018. Immigration Court Backlog Surpasses One Million Cases. TRAC Immigration. Updated November 6, 2018. Available online.

---. N.d. Immigration Court Backlog Tool. TRAC Immigration. Accessed September 29, 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Immigration Court Processing Time by Outcome. TRAC Immigration. Accessed September 29, 2019. Available online.

---. 2018. Judge-by-Judge Asylum Decisions in Immigration Courts FY 2013-18. Accessed September 16, 2019. Available online.

---. 2019. Backlog of Pending Cases in Immigration Courts as of July 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019. Available online.

---. 2019. Burgeoning Immigration Judge Workloads. TRAC Immigration. Updated May 23, 2019. Available online.

---. 2019. Immigration Courts' Active Backlog Surpasses One Million. TRAC Immigration. Updated September 18, 2019. Available online.