You are here

Interlocking Set of Trump Administration Policies at the U.S.-Mexico Border Bars Virtually All from Asylum

A man says goodbye to his partner through the border fence (Photo: BBC)

Through a set of interlocking policies, the Trump administration has walled off the asylum system at the U.S.-Mexico border, guaranteeing that only a miniscule few can successfully gain protection. While the Migrant Protection Protocols, more commonly known as Remain in Mexico, have been a key part of throttling asylum applications, two newer, far less visible programs hold the potential to complete the job.

The Prompt Asylum Case Review (PACR) program and the Humanitarian Asylum Review Program (HARP), which are byproducts of the administration’s newly implemented rule barring asylum eligibility for individuals who transit through another country to reach the U.S.-Mexico border, aim to adjudicate any humanitarian claims and remove within ten days those who do not meet the standards. First piloted in El Paso last October, the two programs have been rolled out across other sections of the border recently, giving the government new tools to deny the vast majority of protection claims made by Central Americans, Mexicans, and, potentially, migrants from other corners of the world.

In the process, the administration has achieved another promise of the Trump presidency: Virtually ending “catch and release”—a catchphrase to describe a policy that allows release of migrants after apprehension to live in the United States while their asylum claims are being processed. The administration has accomplished this by executing a sequence of policies that erect a range of consequences for migrants arriving at the border—particularly for families, who in the last few years have constituted the bulk of those seeking asylum and have been released while waiting for their claim to be decided. “This administration’s networks of policies and international agreements have enabled [U.S. Customs and Border Protection] to apply [a] consequence or alternative pathway to almost 95 percent of those who we apprehend, rather than releasing them into the interior of the United States,” CBP Commissioner Mark Morgan testified February 27 at a House Appropriations subcommittee hearing.

Until recently, migrants arriving at the southwest border without proper documentation were either released or detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). And families, even when detained, were released relatively soon after. Families and children have made up increasing shares of migrants apprehended at the border since 2014. In fiscal year (FY) 2019, they accounted for almost two-thirds of those taken into custody after crossing the border illegally. And 91 percent of those families came from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. At the same time, the number of migrants apprehended from countries other than these three and Mexico, which in years prior had amounted to a relative trickle, nearly quadrupled over the course of a year—reaching 77,000. Border apprehensions hit 133,000 in May 2019—the highest monthly tally since March 2006. With resources stretched to the breaking point, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) searched for new ways to tamp the flows.

With PACR and HARP added to a mix of other tools, DHS now has more policy choices at its disposal to deal with migrants arriving at ports of entry without valid documentation or crossing the U.S.-Mexico border illegally. And overhanging these border initiatives are decisions by the Attorney General that since 2018 have narrowed the qualifying criteria for asylum, eliminating possible claims related to gang or domestic violence or the fear of persecution because a relative has been persecuted.

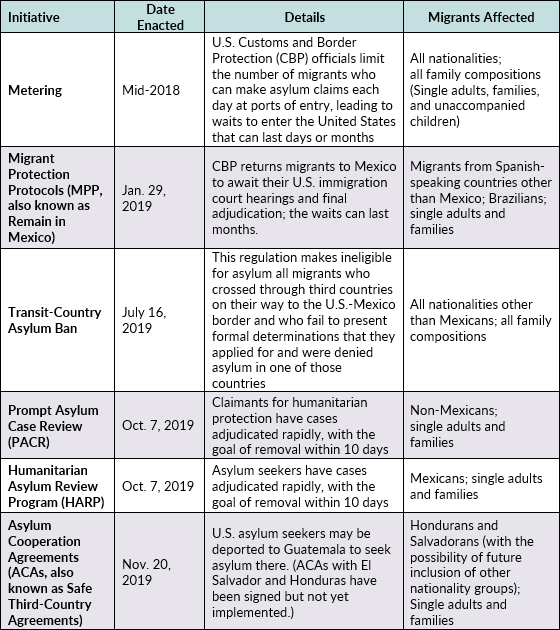

With the layered approaches at the border, opportunities for asylum seekers to enter the United States are sparse and seemingly confined to migrants from non-Spanish speaking countries. However, with the arrival of the PACR program, which reportedly is currently principally applied to Central Americans, the infrastructure is now in place to apply it to migrants from non-Spanish speaking countries as well. The programmatic and policy building blocks of this web of interconnected policies have been built steadily since 2018, as Table 1 reflects.

Table 1. Consequences for Migrants at the U.S.-Mexico Border, as of February 2020

The array of options for DHS presents a number of advantages for the administration. First, their multiplicity provides immunity from court injunctions: if one measure were to be struck down, others could be employed. Second, they introduce an element of uncertainty and chaos into migrants’ decision-making. A Honduran crossing the border with his child does not know whether they will be sent back to Mexico, removed to Guatemala, returned to Honduras, or possibly be released into the United States. Finally, the different options allow resources to be tailored to how distinct populations are likely to seek entry into the United States, and thereby work in coordination to curtail entry across the board.

Following is a look at the individual strategies, in the order in which they were implemented.

Metering

Metering, which is the imposition of limits on the number of people who can apply daily for asylum at a port of entry, has been in effect for the longest of any of the active programs. To be sure, it was first implemented by the Obama administration in 2016 to deal with the surge of Haitians arriving at the San Ysidro port of entry in California. However, the Trump administration scaled it up and expanded it to most ports of entry, and has subjected all nationalities to it, including Mexicans seeking asylum. At its height, in August 2019, University of Texas researchers documented 26,000 people on waitlists across the border.

Migrant Protection Protocols

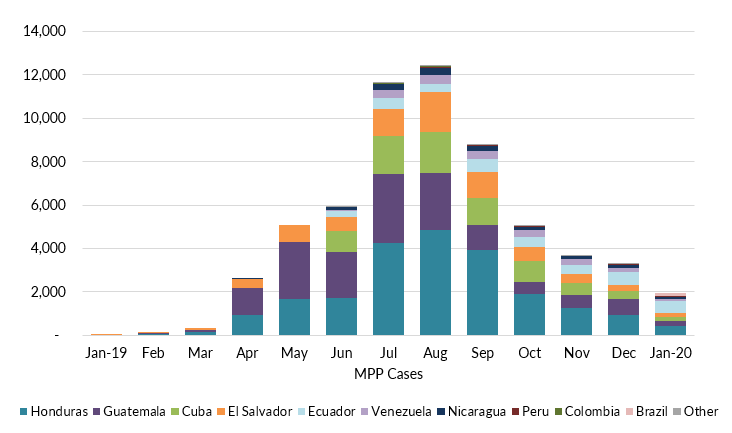

MPP, initially implemented in January 2019, was scaled up following a June 9, 2019 agreement between the United States and Mexico. The latter signed the agreement under threat of U.S. tariffs, pledging to accept and hold more migrants back under the program widely known as Remain in Mexico, and increase its own immigration enforcement. Since then, MPP has expanded geographically (it is operational in all but one section of the border—Big Bend, Texas) and in terms of nationalities subject to it. Even so, the number of people placed in the program monthly has decreased since August 2019.

All migrants from Spanish-speaking countries (regardless of whether they speak Spanish themselves), besides Mexico, can be placed in MPP, and a total of 59,000 have been. The program was expanded to Brazilians (most of whom speak Portuguese) as of January 29. When MPP was at its height in summer 2019, most migrants sent back to Mexico were from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In recent months, MPP seems to be DHS’ program of choice for migrants from other countries (see Figure 1). While more than 9,000 Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and Hondurans were placed in MPP in August, just over 800 were in January. On the other hand, the number of Ecuadorians, for example, placed in MPP has remained relatively steady since July, when 500 were put into MPP; there were 552 in January, the most migrants of any one nationality returned that month.

Figure 1. Nationalities of Migrants Placed in MPP, January 2019-January 2020

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Details on MPP (Remain in Mexico) Deportation Proceedings,” accessed February 21, 2020, available online.

This shift is likely a function of two phenomena: the overall flow of migrants from the three Central American countries is decreasing, and the administration is employing other options for Central Americans—options not currently applicable to other nationalities, such as Ecuadorians.

The scaled-down reliance on MPP may also be intentional. There was always a question about how long Mexican border cities would tolerate hosting thousands of migrants as a favor—or a price to be paid—to the United States. Thus, lower numbers may actually ensure MPP’s continued viability.

Transit-Country Asylum Ban

The transit-country asylum ban is now arguably the most potent weapon available to DHS by making the entire asylum system off-limits to the vast majority of migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. Introduced as an interim final rule on July 16, 2019, the Supreme Court in September 2019 cleared the way for DHS to apply it to all non-Mexican migrants who cross the southwest border or arrive at a port of entry without valid documents. Those who transit through another country and who cannot demonstrate they applied for, and were denied asylum there, are now ineligible to apply for asylum in the United States. In the months since the ban has been implemented, approval rates for the initial stage of an asylum process (the credible-fear interview) have declined from 80 percent in June 2019 to 45 percent in December. This is likely explained by the fact that migrants deemed ineligible to apply for asylum under the new transit-country rule are formally treated as having failed the credible-fear determination.

PACR and HARP

Though targeted at different populations—PACR at non-Mexicans and HARP at Mexicans—the two programs have the same aim: to quickly process migrants’ asylum and other humanitarian protection claims and remove those whose claims fail, within a ten-day period. Those placed in these programs are held in CBP custody for the duration of their proceedings, whereas in the past, asylum seekers would be transferred to ICE custody. CBP facilities have stricter visitation limitations, which reduces migrants’ access to counsel and ability to place phone calls.

Under PACR, non-Mexicans ineligible for asylum can apply for two other forms of humanitarian protection: withholding of removal and deferral or withholding of removal under the Convention against Torture. However, they must pass a “reasonable-fear” test, a standard that is higher than credible-fear determinations for asylum, establishing that they are “more likely than not” to be persecuted or tortured if returned—a test very few can pass, particularly without assistance of counsel.

Mexican nationals seeking asylum receive a credible-fear determination under HARP, having to meet a standard showing a “significant possibility” that they would qualify for asylum. Mexican asylum seekers have one of the lowest asylum grant rates (11 percent in fiscal year 2019) of any nationality, so it is likely that their credible-fear grant rates are also lower and that despite not being subject to the transit-country asylum ban, many can be quickly removed. Migrants in both programs may request that an immigration judge review the outcome of their determination—a review now typically done telephonically.

DHS has expanded PACR and HARP over the four months they have been in place. Ken Cuccinelli, the acting Homeland Security deputy secretary, announced February 25 that both programs had been implemented across the border. Both started as pilots in the El Paso sector in October 2019. According to DHS data provided to the House Judiciary Committee, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) completed interviews in 398 PACR cases and 189 HARP cases between October 11 and December 9, 2019. By February 27, CBP stated that a total of slightly more than 1,200 migrants had been placed in HARP and nearly 2,500 in PACR, and a lawsuit against the programs revealed that more than 700 had been removed through PACR.

Asylum Cooperation Agreements

The ACAs also started small and have recently been scaled up. The only ACA to be implemented, with Guatemala, went into effect November 20, 2019. At first, only single adults were deported to Guatemala. But on December 12, DHS expanded removals to families. The program applies to migrants seeking asylum and who do not affirmatively state that they fear persecution or torture in Guatemala, and, if they did state that, they must have failed to show that such persecution or torture is more likely than not to occur. By February 25, more than 700 migrants from El Salvador and Honduras had been removed under the agreement, a number that appears almost double the tally on January 31.

If the rate of removal to Guatemala remains at the same level going forward, it would represent about 10 percent of all Hondurans and Salvadorans arriving at the border monthly. If DHS capacity continues to increase and flows continue to decrease, deportation to Guatemala will become a possible outcome for an even higher share of these migrants.

ICE Detention

While the building blocks of metering, MPP, the transit-country asylum ban, HARP, PACR, and the ACAs have made it possible to effectively stop releasing large numbers of migrants into the United States after apprehension, CBP continues to rely on ICE to detain some migrants, particularly single adults. Not surprisingly, as the use of these programs has increased, the detention rate has decreased. In November 2018, more than 50 percent of border arrivals were detained by ICE. As apprehensions increased through May 2019, the detention rate decreased, reflecting resource constraints and the fact that CBP stopped transferring most families to ICE around March 2019. Since then, as the number of total arrivals has decreased and the share of those arrivals who are single adults (who are more amenable to ICE detention) has increased, detention rates have risen slightly—but still reached only 36 percent in December 2019. This indicates that CBP is likely making a choice not to detain everyone who could possibly go into ICE detention, prioritizing the use of other consequence programs instead.

Future Expansion?

Today, the only migrants who have more than a slim chance of being released into the United States while awaiting their immigration court date are families from non-Spanish speaking countries (other than Brazil). If DHS convinces Mexico to accept other nationalities under MPP, or further expedites removal procedures and scales up removal flights after these nationals are processed through PACR, this last category will perhaps disappear as well.

The Trump administration may have been successful in bringing under control flows that surged in 2018 and 2019. But its actions have come at a price, failing to take into account the worsening conditions in many of the sending countries, and the possibility of crime and violence facing migrants sent to Mexico and Guatemala. Human Rights First, for example, has documented more than 800 public reports of violent crimes against migrants waiting in Mexico under MPP. Collectively, the policies also push others through the U.S. asylum system with only the thinnest veneer of due process.

- Interim Final Rule establishing the transit-country asylum ban, “Asylum Eligibility and Procedural Modifications”

- Asylum Cooperation Agreement with Guatemala

- Congressional letter to Homeland Security Acting Secretary Chad Wolf on PACR and HARP

- Government reply brief in Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center v. Wolf

- ICE detention statistics

- Flowchart from the Congressional Research Service showing border processes under MPP, the transit-country asylum ban, and the Guatemala ACA

- Data and report on MPP from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse

- November 2019 Metering Update by the University of Texas’ Strauss Center

- KRGV article on the expansion of PACR

- Washington Post article on the shift away from MPP and toward PACR and the ACA for Central Americans

National Policy Beat in Brief

Federal Agencies Strike Back Against Sanctuary Policies. In January and February, the Justice Department and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) stepped up actions against states and localities (often known as sanctuary jurisdictions) that limit cooperation with federal immigration authorities. DHS suspended enrollment and re-enrollment for New York State residents in some trusted traveler programs, announced it would deploy Border Patrol agents to support immigration enforcement in some large U.S. cities, and began filing administrative subpoenas for information against a number of states and localities on removable noncitizens released from local detention. The Justice Department has filed lawsuits against a number of states and localities for their “sanctuary” policies.

On February 5, DHS announced its temporary suspension of New Yorkers’ enrollment in the Global Entry, NEXUS, SENTRI, and FAST programs, following implementation of the state’s Green Light Law on December 14. The law allows unauthorized immigrants to apply for driver’s licenses, and prevents agencies including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) from accessing Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) databases without a court order. Without access to DMV databases, DHS says it cannot validate an individual’s qualification for membership in the four trusted traveler programs or verify other relevant information, including biographical details and criminal history.

In a move that garnered headlines across the nation, CBP on February 14 confirmed that it would deploy 100 Border Patrol agents, including some members of a special tactical unit known as BORTAC, to a handful of major U.S. cities to assist ICE with interior enforcement operations. The deployment will last through May.

And in a range of actions since January 13, ICE has subpoenaed local and state law enforcement agencies in Connecticut, New York State, and Oregon, as well as Denver; Hillsboro, Oregon; San Diego County, and the following Oregon counties: Clackamas, Wasco, and Washington. Even though the subpoenas are administrative, federal prosecutors can ask a federal judge to enforce them in the event law enforcement agencies do not comply, as they have done in Denver and New York. ICE has not previously used subpoenas to obtain information on noncitizens in or released from state or local custody; the agency maintains that policies limiting communication necessitate the move.

On January 24, the Justice Department sued California, challenging a law that bans the operation of private detention facilities after January 1, 2020. On February 10, the Trump administration filed two more lawsuits, one to challenge a New Jersey law enforcement directive that limits cooperation with federal immigration authorities, and another against a King County, Washington, executive order that aims to prevent deportation flights from taking place at the local airport.

- Letter from Homeland Security Acting Secretary Chad Wolf announcing suspension of trusted traveler program enrollment for New Yorkers

- Text of New York’s Green Light Law

- ICE press release on subpoenas issued in Oregon

- Complaints filed by the Justice Department in lawsuits against California, New Jersey, and King County

- New York Times article on DHS trusted traveler program suspension

- Washington Post article on deployment of Border Patrol agents

- Associated Press article on enforcement of subpoenas in New York

President Trump Adds Six Countries to Travel Ban. On January 31, President Trump signed a proclamation expanding travel restrictions to nationals of six additional countries, effective February 21. Citizens of Eritrea, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, and Nigeria are barred from receiving immigrant visas to the United States, unless they qualify for a waiver. Nationals of these countries are still eligible to receive nonimmigrant visas, such as tourist or student visas. Nationals of Sudan and Tanzania are prohibited from receiving visas through the diversity visa lottery, which grants up to 55,000 green cards to immigrants from under-represented countries; Tanzanians and Sudanese can still immigrate to the United States through other pathways. DHS stated that restrictions were added because of deficiencies in these countries’ identity-management capacities and in information-sharing with the United States. The six countries join seven others (Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen) that are already subject to restrictions under the 2017 travel ban.

- Presidential proclamation on “Improving Enhanced Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry”

- Wall Street Journal article on the expanded travel ban

Administration Diverts Additional Military Funds to Border Wall Construction. The Defense Department notified Congress that it would transfer $3.8 billion from various military accounts to fund construction of barriers, roads, and lighting along the U.S.-Mexico border, under its authority to support counterdrug operations of other federal agencies. The funds will reportedly pay for 177 miles of border wall. This transfer will bring the total amount spent on the wall to almost $15 billion under this administration. While the administration requested just under $2 billion for wall construction in its fiscal year (FY) 2021 request to Congress—$3 billion less than its FY 2020 request—it may now be relying more heavily on such executive-branch transfers.

- Defense Department reprogramming notice submitted to Congress

- NPR article on the transfer of funds

Federal Judge Finds Conditions in Arizona Border Patrol Facilities Do Not Meet Constitutional Standards. On February 19, a federal judge in Arizona ruled that conditions for civil detainees in CBP facilities in the Tucson Sector were “presumptively punitive and violate the Constitution,” finding that they were worse than conditions in criminal or ICE detention. The order requires that migrants not be detained for more than 48 hours in these facilities until CBP can provide them with “a bed with a blanket, a shower, food that meets acceptable dietary standards, potable water, and medical assessments performed by a medical professional.” Though the judge previously issued a preliminary injunction requiring improved conditions in 2016, the February ruling sets higher standards.

- 2016 preliminary injunction in Doe v. Johnson

- 2020 permanent injunction in Doe v. Nielsen (previously Doe v. Johnson)

- Arizona Republic article on the judge’s ruling

ICE Directs Fingerprinting of Minors in Shelter Facilities. ICE officials have begun fingerprinting unaccompanied minors over the age of 14 who are in federal Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) shelters across the country, which ICE officials say will protect against human trafficking. This move, enacted via a field guidance document in January, follows the implementation of ICE and CBP pilot projects that expand the categories of immigrants whose DNA and biometric information is collected. Separately, ICE has acknowledged that it is using confidential notes written by therapists who meet with children in ORR custody to build removal cases against these minors.

- BuzzFeed News article on the new fingerprinting policy

- Washington Post article on the sharing of confidential therapy-session notes with ICE

State/Local Policy Beat in Brief

Maryland Expands State Dream Act. On January 30, Maryland lawmakers in the House and Senate overturned Governor Larry Hogan’s May 2019 veto of a bill that expands the state’s Dream Act, passing it into law. The measure eliminates the previous requirement that unauthorized immigrant students who graduated from a Maryland high school attend a community college before a four-year college in order to qualify for in-state tuition rates.

- Text of Senate Bill 537

- Associated Press article on the Maryland legislature’s veto overrides

Los Angeles Prohibits Private Detention Centers and Facilities for Unaccompanied Children. The Los Angeles City Council on January 31 approved a temporary measure, effective immediately, that blocks the construction and operation of private detention centers and ORR shelters for unaccompanied children in the city. It was passed largely in response to interest from a private company in opening an ORR facility for children. The measure could be extended for up to two years while city officials prepare a new measure with a permanent ban.

Utah Supreme Court Allows DACA Recipients to Apply to State Bar. The Utah Supreme Court announced on January 30 that it agreed to a rule change making Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients eligible to take the state bar exam and be admitted as attorneys. Previously, the court required bar applicants to demonstrate they were legally present in the United States. After two law school graduates who are DACA recipients petitioned the court to change the rule last October, the court proposed a rule change in December, and cemented it last month.

- Text of Rule 14-721, Admission of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipients

- Salt Lake Tribune article on the rule change

The authors thank Luis Marquez for his assistance.