You are here

The Eurasian Economic Union: Repaving Central Asia’s Road to Russia?

Arrivals from Tashkent, Uzbekistan, depart a train in Moscow. (Photo: IOM/Elyor Nematov)

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 resulted in political, economic, and military sanctions from Western powers, leading to its expulsion from the Group of Eight nations. Alongside a rapid decline in oil prices, this ostracization from much of the international community had huge ramifications for Russia’s economy. The value of the ruble against the U.S. dollar fell by approximately half over the course of 2014; as of early 2021, the currency was just a fraction of its value a decade before.

The economic downturn and geopolitical tensions sparked a decline in migration to Russia. Migrant workers and the cheap labor they offered had been key components of Russia’s economic development since the domestic labor shortages of the 1990s, due in part to the country’s negative demographic outlook, with a shrinking population and low birth rate. Most of these migrants have come from Central Asia and have been instrumental in Russia’s post-Soviet economy. They have been involved in construction, domestic services, and farm and factory work.

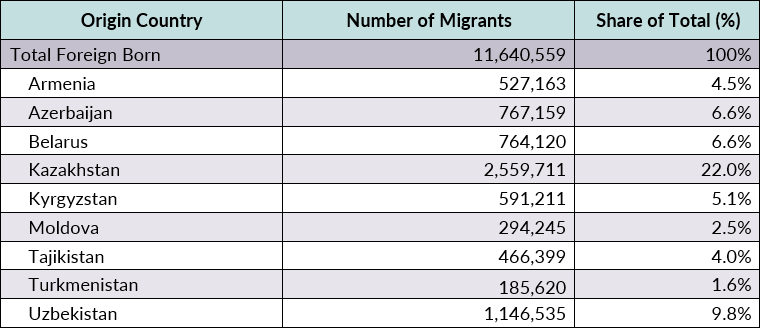

Migrants’ origin countries have come to depend upon remittances they and others in the diaspora send back. In the decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has become one of most important destinations for labor migrants from Central Asia, especially Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. These migration patterns are linked with the legacy of the Soviet economy and infrastructure, which largely centered on Russia, and economic liberalization carried out by Moscow after the disintegration of the Soviet empire. Approximately three-quarters of migrants from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan and nearly 60 percent of those from Uzbekistan in 2013 headed to Russia. In 2019, nearly one-fifth of Russia’s 11.6 million registered foreigners were from these three countries. These countries also were the origin of many migrant laborers in Kazakhstan, a growing destination country due to its oil-driven economic boom. Remittances have played critical roles in the region’s economies.

Table 1. Migrants in Russia, 2019

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), “International Migrant Stock 2019: by Destination and Origin,” 2019 update, available online.

In spite of this, Russia has struggled to develop a clear and consistent migration policy. Moreover, the rise of China’s influence in Central Asia since the early 2000s has limited Moscow’s sway in the region, which it had dominated since the end of the 19th century. China has overtaken Russia as Central Asia’s biggest trading partner, and Beijing has played a significant role through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Belt and Road Initiative, which involves a planned investment of several trillion dollars in infrastructure projects and economic development. Additionally, the European Union’s expansion and the so-called color revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan have increased the Kremlin’s geopolitical and geoeconomic concerns. Still, Russia’s control over migration pathways with Central Asian states appears to function as a geopolitical instrument to compete with China’s growing regional role. And Russian re-engagement with the post-Soviet states serves its effort to regain power, rebuild its international status, and counteract global trends and economic marginalization resulting from Western sanctions.

These internal and external factors contributed to the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which came into effect in 2015 and as of early 2021 consisted of five countries: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia. This article describes the growth of the Eurasian Economic Union and how it functions as a Russian tool to offer Central Asian migrants access to its labor market in exchange for political influence around the region. While still a work in progress, the bloc has successfully smoothed avenues for migrants traveling between member countries, particularly to Russia, and is likely to grow to include Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

From USSR to EEU?

The Eurasian Economic Union was formed using multilateral institutions and frameworks in place following the collapse of the Soviet Union, including the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which has included all former Soviet Union countries minus the Baltic states, as well as the Eurasian Economic Community, the Eurasian Customs Union, and the Single Economic Space. The EEU treaty was initially signed by the leaders of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia in May 2014, and was expanded to include Armenia and Kyrgyzstan the following year. This grand project can be seen as part of Russia’s reintegration in post-Soviet space. The initiative has been driven by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s desire to counteract economic marginalization and re-establish Russia at the heart of an economic alliance. Russia is solidly in the driver’s seat, accounting for 84 percent of the Eurasian Economic Union’s gross domestic product (GDP) as of 2017.

Membership offers countries closer cooperation with Russia, including expanded labor migration pathways. The bloc also provides for the free movement of goods and capital, and offers the prospect for as-yet-unrealized engagement with the European Union, potentially opening the door to a broader Eurasian project countering China’s rise.

At the same time, Russia’s support for the political status quo in Member States means that this union provides stability for ruling regimes aiming to further concentrate power and ensure their sole authority to access and distribute significant political and economic resources without impediment. In other words, the regimes’ political survival can depend on their relations with Russia. For instance, Armenia has a Western-oriented political and economic outlook, but geopolitical constraints—in particular those related to the contested Nagorno-Karabakh territory—have contributed to it joining the Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization, a Russia-led military alliance. For Russia, Armenia is a strategic partner; engagement through these organizations allows it to restrict the regional role of Western powers such as the European Union, which has a Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement with Armenia. Russia played a central role in the peace deal ending the 2020 surge in violence in Nagorno-Karabakh, and its role as a military buffer for Armenia against Azerbaijan, the other primary country involved in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and Turkey, Azerbaijan’s backer in the dispute, will likely contribute to Russia’s continuing sphere of influence in the region through organizations such as the Eurasian Economic Union. In this way, the bloc can be characterized as a strategic tool to expand Russia’s geo-economic and geopolitical interests and influence in the region.

Generally, the Eurasian Economic Union has been characterized as an alliance of authoritarian regimes in which leaders are motivated to cooperate to preserve regime security. In particular, founding members Belarus and Russia have been subjected to Western sanctions over human-rights violations and allegations of suppressing democratic activity, among other activities. Both Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko and Putin have regularly blamed the West and expressed their concerns about interference in their domestic affairs and support for regime change across the Eurasian region by the United States and the European Union.

Easing Labor Migration Pathways

A commitment to easing labor migration is one of the key elements of the Eurasian Economic Union, with remittances instrumental to maintaining stability in the region. For instance, Kyrgyzstan is among the most remittance-reliant countries in the world. Remittance flows to the country in 2019 accounted for 29 percent of its GDP. EEU membership offers more favorable conditions for Kyrgyz migrants in Russia than for foreigners outside the union.

These remittances have raised standards of living in migrants’ origin countries, and helped governments lower borrowing costs, develop infrastructure, and deliver public services, in particular by bolstering the banking and financial system. They have also contributed to the development of the private sector, as this inflow has provided opportunities for banks to offer credit and fostered competition within the financial sector. In addition to financial remittances, the skills that migrants receive abroad can often be put to use upon return to their countries of origin.

Under the EEU treaty, migrants and their families are exempt from requirements that they register within 30 days of entering the territory of another Member State, as most new arrivals must do. Member-State citizens also have the right to own property, receive labor protections such as for joining a trade union, and access various employments benefits. To strengthen labor market integration, Member States must recognize degrees from higher education institutions in each respective country and guarantee education for migrants’ children. The union furthermore gives migrants access to social security benefits apart from pensions or retirement schemes and allows them to seek medical care in accordance with the host state’s domestic legal norms.

Non-EEU Members Face Mounting Barriers

The framework for the larger CIS bloc allows free movement of labor, however on the day of the Eurasian Economic Union’s formation the Russian government enacted restrictions making it compulsory for all migrants from CIS countries who were not EEU members to comply with additional procedures. These rules require migrants in this category to obtain work permits called patents, register with authorities, receive temporary and permanent residence permits, and pass tests on language, history, and legal norms. Migrants, especially from the non-EEU countries of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, have faced difficulties completing all the documentation within the 30 days they are given. Moreover, they often do not know the details of the procedures of registering their work and presence in Russia.

In 2017, less than half of the 4 million foreign workers entering Russia were issued work permits, indicating that many were working illegally. Moreover, a June 2018 regulation imposed further legal requirements for non-EEU migrants to register at both their places of work and residence within seven days of arrival (previously migrants had 15 days to register). This made the situation for migrant workers from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan even more difficult. Russia’s actions have led to the emergence of various informal practices and labor markets, unauthorized workers, and corruption. As a result of regulation breaches, several thousand people from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan were deported between 2017 and 2020.

Tajiks and other migrants from non-EEU countries in Central Asia also have been subjected to abuse and exploitation by employers and police, according to international organizations such as the International Labor Organization (ILO), the United Nations, and Human Rights Watch.

The Holdouts: Tajikistan and Uzbekistan

The Eurasian Economic Union has removed obstacles to labor migration among Member States, however both Tajikistan and Uzbekistan—the origin countries for many migrant workers in Russia—are outside the bloc. At the same time, Tajikistan in particular has depended heavily on remittances. In 2013, remittances made up 44 percent of Tajikistan’s GDP, according to the World Bank. However, Russia’s economic downturn following the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and plunging oil prices have had an impact on migrants, prompting many to leave. New restrictions imposed on non-EEU members were also responsible for this drop in remittances. Remittance inflows to Tajikistan subsequently declined by 45 percent, from U.S. $3.7 billion in 2013 to $1.9 billion in 2016. In spite of this, remittances have steadily increased since then, and in 2019 accounted for $2.3 billion, or 29 percent of Tajikistan’s GDP. These trends are also closely connected with economic hardship in Tajikistan and lack of work opportunities for its citizens, which has further contributed to an increase in illegal migration in Russia.

To lure these two countries to the Eurasian Economic Union, the Russian government has repeatedly emphasized easing restrictions for labor movement and made promises for a more open labor market. Yet the overtures have been rebuffed by long-time Tajik President Emomali Rahmon, who has repeatedly emphasized issues of sovereignty and raised concerns about potential dependence on Russia should his country join the union. His position is reminiscent of Uzbekistan’s isolationist foreign policy under Islam Karimov, the autocrat who ruled until his death in 2016. During this era, Uzbekistan largely refrained from joining Russia-led integration initiatives, though millions nonetheless emigrated for work on a seasonal basis. Karimov repeatedly emphasized that it would not be in Uzbekistan’s interests to join the Eurasian Economic Union, which stirred memories of Soviet imperialism.

Since Karimov’s death, Russia has been pushing Uzbekistan, which is far and away the most populous country in Central Asia, to become an EEU member. His successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, has been open to cooperation. Mirziyoyev’s foreign policy has been more pragmatic, seemingly aiming to balance domestic and regional geopolitical realities, including China’s growing role and Uzbekistan’s location amid some of the world’s strictest autocratic regimes, which makes it difficult to attract Western investment. The Uzbek government has implemented various foreign policies aimed at fostering better relations with its regional neighbors and the international community writ large, including attracting foreign investment.

Uzbekistan seems primed to join the Eurasian Economic Union in the near term. In an address to the nation in January 2020, Mirziyoyev said the government was looking to cooperate with the bloc. He also stressed that, apart from investment and broader economic benefits, “integration means better conditions for our migrants in Russia and Kazakhstan.” In December, Uzbekistan was officially granted observer status, on par with Moldova and Cuba. If Uzbekistan does become a full EEU member, Tajikistan might be prompted to follow suit to avoid being marginalized in the region. It might also be attracted by opportunities to reduce its debt reliance on China, its main creditor.

The Fate of the Eurasian Economic Union Post-Pandemic

Migration has been an important component of Russia’s post-Soviet policy towards Central Asia. It has been used to make Central Asian countries reliant on Moscow and preserve Russian influence in the region. Yet this system was thrown into disarray following the COVID-19 outbreak, which prompted the closure of national borders and left the lives of several million migrants in limbo. As elsewhere, border shutdowns, lockdowns, travel bans, and social distancing measures brought businesses and economic activities to a standstill. This had particularly acute effects for migrants in Central Asia and Russia. Millions were left unemployed, unprotected, and stranded, with significant ramifications for origin countries’ economies. Remittances from Russia to Central Asia were 23 percent lower in the second quarter of 2020 than in 2019, according to the World Bank.

Tajikistan was especially hard hit; remittances there were 41 percent lower in the second quarter of 2020 than during the same period in 2019. Going forward, Tajikistan faces several economic structural challenges. According to the World Bank’s projection, its economy could be further hindered by the increase in food prices and falls in growth and remittances.

These conditions could make the Eurasian Economic Union more attractive for Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Member States’ growing reliance on Russia was demonstrated by the August 2020 presidential elections in Belarus, which prompted political demonstrations and protests in the streets which were suppressed by state authorities. The European Union rejected the results of the election, and Lukashenko’s increasing reliance on Putin’s support suggests that post-Soviet authoritarian regimes’ political legitimacy and survival largely depend on their relations with Russia.

To reclaim its status as a great power, Russia has relied on its dominant position in the post-Soviet Eurasian region. The Eurasian Economic Union is one of the key elements of Russia’s Eurasianist foreign policy, which is at the core of Putin’s broader Eurasian integration agenda. This approach positions Russia as the pivot of Eurasia, a region that it frames as synonymous with the post-Soviet space and which it lays claim to lead by virtue of its geographic and economic power.

International changes since the early 2000s—such as significant increases in China’s regional role and tensions with the West, including political and economic sanctions—have provided further impetus for Russia to strengthen blocs such as the Eurasian Economic Union. Putin has been trying to lure Central Asian countries to join the bloc using various economic and geopolitical tools, especially those under the banner of security and economic integration projects. Looking ahead, the Eurasian Economic Union is likely to expand and grow stronger in coming years, due to the illiberal nature of Central Asian political and economic systems, countries’ high dependence on remittances, and focused pressure from Russia.

Sources

Dragneva, Rilka and Kataryna Wolczuk. 2017. The Eurasian Economic Union: Deals, Rules and the Exercise of Power. London: Chatham House. Available online.

Eurasian Economic Union. 2014. Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union. May 29, 2014. Available online.

Human Rights Watch. 2019. Russia: Police Round Up Migrant Workers. Press release, December 24, 2019. Available online.

Lemon, Edward. 2019. Dependent on Remittances, Tajikistan’s Long-Term Prospects for Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction Remain Dim. Migration Information Source, November 14, 2019. Available online.

Malyuchenko, Irina. 2015. Labour Migration from Central Asia to Russia: Economic and Social Impact on the Societies of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Central Asia Security Policy Brief No. 21, OSCE Academy, Bishkek, February 2015. Available online.

Olimova, Saodat and Igor Bosc. 2003. Labour Migration from Tajikistan. Dushanbe: International Organization for Migration. Available online.

President of Uzbekistan. 2020. The President Takes Part in the Eurasian Economic Union Online Summit Meeting. Press release, December 11, 2020. Available online.

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2020. Uzbekistan Says It Will Be 'Observer' Of Russia-Led Trade Bloc. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, March 7, 2020. Available online.

Ratha, Dilip et al. 2020. Phase II: COVID-19 Crisis through a Migration Lens. Migration and Development Brief No. 33, Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD)/World Bank, Washington, DC, October 2020. Available online.

Roberts, Sean. 2017. The Eurasian Economic Union: The Geopolitics of Authoritarian Cooperation. Eurasian Geography and Economics 58 (4): 418-41.

Ter-Matevosyan, Vahram, Anna Drnoian, Narek Mkrtchyan, and Tigran Yepremyan. 2017. Armenia in the Eurasian Economic Union: Reasons for Joining and Its Consequences. Eurasian Geography and Economics 58 (3): 340-60. Available online.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. International Migrant Stock 2019: by Destination and Origin. Available online.

---. 2019. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. New York: United Nations. Available online.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2015. Labour Migration, Remittances, and Human Development in Central Asia. New York: UNDP Regional Bureau for Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Available online.

World Bank. N.d. The World Bank in Tajikistan. Accessed December 29, 2020. Available online.

World Bank Prospects Group. 2020. Annual Remittances Data, October 2020 update. Available online.