You are here

Costa Rica Has Welcoming Policies for Migrants, but Nicaraguans Face Subtle Barriers

Merchants sell items on a busy street in San José, Costa Rica. (Photo: Cynthia Flores/World Bank)

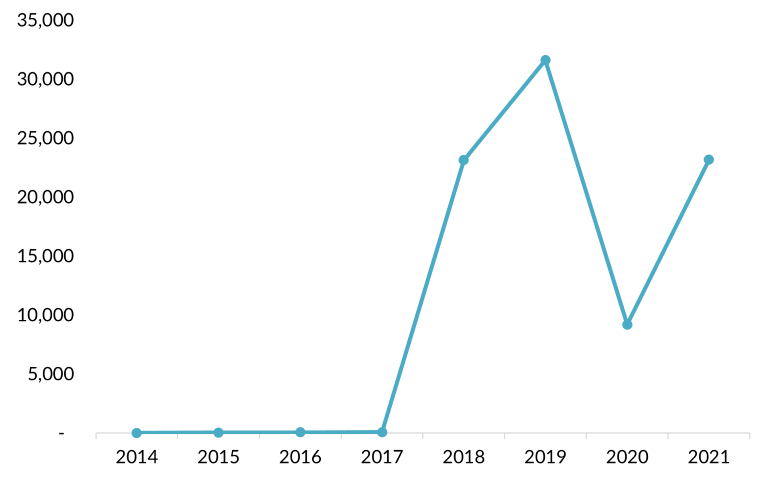

Emigration from Nicaragua has spiked in recent months amid a new government crackdown, resuming a trend that started in 2018 but was slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Ahead of the November 7 general election, authorities have arrested political dissidents, aspiring presidential candidates, and journalists, prompting many citizens to seek protection abroad. Nearly 23,200 Nicaraguans sought asylum in Costa Rica between January and mid-September 2021, according to official data shared with the author, mostly since June. They joined the nearly 64,000 Nicaraguans who applied for refugee status in Costa Rica between 2018 and 2020, on the heels of unrest that began with protests over proposed changes to the national pension system and evolved into broader government repression.

Nicaraguan migration to Costa Rica, its southern neighbor, is one of Central America’s most prominent and important migration flows. As of 2020, 368,000 Nicaraguans lived in Costa Rica according to the Costa Rican government, comprising approximately 7 percent of the country’s approximately 5 million residents (there is also a significant population of unauthorized migrants from Nicaragua, estimated to be as large as 200,000 people). Costa Rica is the top destination for Nicaraguans globally, followed by the United States. This migration route was formed by seasonal labor migration dating back to the 19th century but has boomed since 1990 with growing demand in the construction, agricultural, and domestic services sectors.

Humanitarian migrants have also arrived in Costa Rica during periods of conflict in Nicaragua in recent decades, as is the case today. While Nicaraguans accounted for a tiny share of asylum seekers in the country before 2017, they made up 83 percent of applicants in 2018 and 86 percent so far in 2021.

Figure 1. Asylum Applications by Nicaraguans in Costa Rica, 2014-21*

* Data for 2021 are through August.

Source: Author’s analysis based on data from Costa Rica’s Refugee Unit.

While Costa Rica maintains a policy of being receptive to asylum seekers and other migrants, new arrivals nonetheless often face social exclusion, discrimination, and stigma. Hostility has historically been latent in Costa Rican-Nicaraguan interpersonal relations, but it has flared at times, including since 2018. Amid a growing influx of asylum seekers, Costa Ricans shouting anti-immigrant chants marched in August 2018 to a San José park known as a gathering place for Nicaraguans. This episode—described as the first anti-immigrant rally in Costa Rica’s modern history—surprised the world and seemed at odds with the popular perception of the country as hospitable and supportive of peaceful interaction, which has earned it a reputation as the “Switzerland of the Americas.” Tensions have been on the rise since, and were further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although Costa Rica was able to control transmission during the first wave of the virus’s spread, the Nicaraguan government did not take containment precautions as seriously; as contagions spiked during a second wave in Costa Rica, many blamed Nicaraguan arrivals.

This article, based on 32 interviews conducted by the author in San José in 2020 as part of a research project, provides an overview of the legal and social context for Nicaraguan migrants in Costa Rica. Although the country prides itself on its integration efforts, Nicaraguans have often reported social isolation and stigma, which can create informal barriers to education, work, and their broader integration.

History with Immigrants

While Latin America has historically been a migrant-sending region, Costa Rica stands out as a receiving country, due in large part to its relative economic success and political stability. Nicaraguans are far and away the largest immigrant group, but migrants from across the Americas (including the United States) and, to a lesser extent, farther away have settled in Costa Rica. Accounting for the large numbers of immigrants believed to have irregular status, as much as 15 percent of the country’s population may be foreign born. Porous borders with Nicaragua to the north and Panama to the south mean that many migrants come for short periods or commute across the border daily. Recently, Costa Rica has also served as a transit country for extracontinental migrants trying to reach the United States.

Costa Rica has been lauded for its pioneering migration framework, including the 2010 General Migration Law which places an emphasis on human rights and integration. Compared to other countries in the region, Costa Rica has a well-developed humanitarian protection system that allows access to work and temporary legal status during applicants’ asylum adjudication.

Moreover, as other Central American nations have grappled with political and generalized violence, Costa Rica has taken pride in having abolished its army, championing peace, and redirecting security funds to social services. As a result, the country’s dominant cultural narrative portrays it as a peaceful democracy and middle-class nation in a sea of instability. This contributes to nationalistic impulses and has played a role in the country’s growing anxiety about immigration. On top of this, racial overtones are strong in popular Costa Rican narratives, and discussions of immigration are often overlaid with race, as many migrants from rural Nicaragua tend to have darker skin tones than urban-dwelling Costa Ricans. This is a trend that can be traced back to colonial times, and associates Costa Rican nationality with Whiteness and nationalities of other regional countries with Indigeneity or Blackness. These narratives are particularly salient in the Central Valley surrounding the affluent and cosmopolitan San José, the country’s most populous city and where most recent Nicaraguan asylum seekers have arrived.

Central America’s Land of Opportunity?

Given Costa Rica’s relative political, social, and economic stability, it has been perceived as a land of opportunity by Nicaraguans (and, to some degree, other Central Americans) fleeing political and economic turmoil, as well as retirees and investors from the United States and Europe. For Nicaraguans, migration to Costa Rica has led to opportunities for their children to make significant educational gains and experience upward social mobility. Nonetheless, Nicaraguans appear to hit a glass ceiling. When the recent wave of migration began in 2018, only 2 percent of Nicaraguan adults (ages 15 to 65) in Costa Rica had a college degree or equivalent, compared to 9 percent of the native born, according to the National Household Survey. Notably, other immigrant populations in Costa Rica had much higher education attainment rates; among Venezuelans, for instance, around 72 percent had a tertiary degree (this likely reflects the relative high status of Venezuelans who are able to travel to Costa Rica).

While Nicaraguan students can easily access K-12 education, high tuition for non-Costa Ricans and ineligibility to receive financial aid impose barriers on their access to postsecondary education, halting or limiting their further social mobility. This has contributed to Nicaraguans' precarity; many work in low-skilled jobs and in the informal economy. Although Costa Ricans have had higher unemployment rates than Nicaraguan immigrants, the latter mostly work in sectors with poor labor conditions.

These labor prospects have placed Nicaraguan migrants in an unusually vulnerable economic situation, particularly during the pandemic, with many becoming food insecure and having to sleep in the streets. In mid-2020, more than three-quarters of Nicaraguan immigrants were going hungry, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and 14 percent were eating no more than once per day—a fourfold increase from pre-pandemic levels.

Exclusion and Barriers in School

Costa Rican law promises all children the right to basic primary and secondary education, regardless of nationality or legal status. Indeed, only 11 percent of Nicaraguan asylum seekers reported difficulties accessing schooling in a 2019 survey.

However, students’ experiences within the education system vary greatly, and Nicaraguans have often reported stigma, discrimination, and other barriers. The government does not require placement testing for all new students, so asylum seekers and other migrants who lack official school transcripts from their country of origin are often evaluated for placement level on a case-by-case basis. School authorities take into account the student’s age and other factors, but negative preconceptions about Nicaraguan children sometimes means they must repeat a school year.

One example is Alan (names of interviewees have been changed in order to preserve their anonymity), a 17-year-old Nicaraguan asylum seeker who arrived in 2018 and told the author school officials tried to make him repeat his junior year because they did not believe he had would be able to keep up with Costa Ricans his age. His native-born classmates reflected this thinking, asking him how he could be so intelligent if he was from Nicaragua. Similarly, authorities tried to push back Adela, who arrived in Costa Rica in the midst of her second grade. In both cases, school authorities justified their decisions by claiming that educational levels in Nicaragua were lower than in Costa Rica, although the students were successful in entering school at their preferred grade level.

Moreover, stigma can result in Nicaraguan students facing social exclusion and harassment, particularly because of their accents. In school settings, pejorative jokes, comments, and graffiti targeting Nicaraguans have often gone unpunished or been made by teachers themselves. A 2018 study found that nearly 60 percent of immigrant students from Nicaragua reported feeling rejected, compared to only 9 percent of Costa Ricans.

Costa Rican schools are required to have intercultural education programs that foster knowledge of different cultures. Yet curricula tend to exclude positive references to Nicaragua. When Nicaragua is mentioned, it is commonly linked to oppression of Costa Ricans. For example, the scholar Ana Solano-Campos has noted that during a re-enactment of the 1856 battle in which Costa Ricans defeated American mercenary William Walker, school narratives have associated Nicaraguans with Walker, omitting the many Nicaraguans who fought against him during their own civil war. This rhetoric helps to build an ideology inhibiting Nicaraguan immigrant children from feeling proud of their national heritage.

These bureaucratic, social, and academic experiences can have a psychological effect on Nicaraguan youth. Carlos, who was born in Costa Rica to Nicaraguan parents, told the author he became conscious in first grade of what it meant to be a child of Nicaraguan immigrants. He had not examined his origins up to that moment, but after being exposed to hostility from students of native backgrounds he started “little by little tucking away [his] Nicaraguan identity.” Carlos said throughout elementary and middle school he was ashamed his parents were Nicaraguan. He adopted a Costa Rican accent at a very young age, making it easier to hide his parents’ nationality and pass as being of Costa Rican heritage. Carlos claimed his lighter skin color also made it easier for him to deny his Nicaraguan connection. In high school he decided to stop passing and embrace his heritage, which he described as similar to coming out as gay.

Regardless of skin tone, young children with Nicaraguan heritage have actively used the practice of passing to avoid stigma. Adela was confronted with stigma against Nicaraguans soon after she arrived in Costa Rica. Her native-born peers excluded her from social groups, and she later began passing as Costa Rican in secondary school in order to get ahead. By the time she started university she had developed a perfect Costa Rican accent. Her childhood best friend was also a Nicaraguan who passed as Costa Rican, although rather than bonding about their shared experiences Adela said they never discussed the issue.

Nicaraguans in Higher Education and the Workforce

When large numbers of Nicaraguan asylum seekers started to arrive in 2018, they changed the migration landscape. Long accustomed to economic migrants who came from Nicaragua with little education, Costa Rica was now witnessing the arrival of some university students and professionals: in 2019, around 23 percent of asylum seekers were university students and 8 percent were doctors. Costa Rica’s legal framework was not prepared. In 2018, the government urged universities to grant access to Nicaraguan students, yet processes remained at the discretion of university authorities. Nicaraguan asylum seekers who spoke with the author reported that academic officials treated them with hostility, denied them information, and refused to accept their documentation from Nicaragua. Some alleged discrimination by both professors and fellow university students. In one case, a professor told an immigrant student in front of the entire class that he would be ashamed of identifying as Nicaraguan.

Stigma has followed Nicaraguan migrants into the workforce. Daniel, who had a sales job, said he lost customers’ trust and missed out on closing deals due to his accent and identity, an issue which his boss noted and discussed with him. Another young Nicaraguan woman, Laura, was told by a potential employer that she needed to lose her accent to get a job that would involve her being the public face of the company.

Mariela, who hid her identity while in nursing school, said being Nicaraguan or living in a neighborhood with many Nicaraguan immigrants might make individuals fear their job applications will be rejected out of hand. For Stella, passing at work left her feeling like a “chameleon,” afraid to speak in meetings and only able to shed her costume at home.

Looking Forward

Nicaraguan immigrants’ on-the-ground experiences shine light on the informal barriers to integration that many face, which could be preventing them from attending higher levels of education and being employed in more lucrative professions. As thousands of people continue to leave Nicaragua for Costa Rica, it will be increasingly important to understand these barriers, and the ways in which immigrants circumvent them by passing as Costa Rican or engaging in other strategies. Failure to do so could have long-lasting repercussions for Nicaraguans in Costa Rica, particularly if they remain for several years as conditions in their native country deteriorate.

These informal integration barriers are hard to measure using quantitative instruments. Officially, Costa Rica’s legal frameworks are generous regarding migrants and asylum seekers’ access to education and the workforce. But school enrollment and unemployment statistics do not fully describe how Nicaraguans and other immigrants fare. Broadening the scope of Costa Rica’s public policy to include strategies around social cohesion might yield benefits in terms of creating more fruitful and meaningful roles for this growing immigrant group.

Sources

Alvarenga, Patricia. 2004. Passing: Nicaraguans in Costa Rica. In The Costa Rican Reader: History, Culture, Politics, eds. Steven Palmer and Iván Molina. London: Duke University Press.

BBC News. 2019. Nicaragua Refugees: 'I Don't Understand Why People Hate Us.’ BBC News, April 19, 2019. Available online.

Blyde, Juan S. 2020. Heterogeneous Labor Impact of Migration across Skill Groups: The Case of Costa Rica. Working Paper No. IDB-WP-1145, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC, August 2020. Available online.

Campos-Saborío, Natalia et al. 2018. Psychosocial and Sociocultural Characteristics of Nicaraguan and Costa Rican Students in the Context of Intercultural Education in Costa Rica. Intercultural Education 29 (4): 450-69.

Campo-Engelstein, Lisa and Karen Meagher. 2011. Costa Rica’s ‘White Legend’: How Racial Narratives Undermine Its Health Care System. Developing World Bioethics 11 (2): 99-107.

Castro, Lenny. 2021. Colombia, Panamá y Costa Rica adoptan medidas por migración hacia EE. UU. Voice of America, August 13, 2021. Available online.

Chaves-González, Diego and María Jesús Mora. Forthcoming. The State of Costa Rican Migration and Immigrant Integration Policy. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Confidencial. 2021. 19 mil nicaragüenses solicitan refugio en Costa Rica en lo que va de 2021. Confidencial, September 2, 2021. Available online.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). 2019. The Forced Migration of Nicaraguans to Costa Rica. Washington, DC: IACHR. Available online.

Locke, Steven and Carlos J. Ovando. 2012. Nicaraguans and the Educational Glass Ceiling in Costa Rica: The Stranger in Our Midst. Power and Education 4 (2): 127-38. Available online.

Malone, Mary Fran T. 2018. Fearing the “Nicas:” Perceptions of Immigrants and Policy Choices in Costa Rica. Latin American Politics and Society 61 (1): 1-28.

Mora, María Jesús. 2020. Costa Rica’s Covid-19 Response Scapegoats Nicaraguan Migrants. North American Congress on Latin America, July 14, 2020. Available online.

Oreamuno, Elizabeth Marie Lang. 2020. Costa Nica: Ser nicaragüense en Costa Rica durante el COVID-19. DelfinoCR, August 3, 2020. Available online.

Organization of American States (OAS). 2020. Situación de los migrantes y refugiados venezolanos en Costa Rica. Washington DC: OAS. Available online.

Paniagua-Arguedas, Laura. 2006. La Palabra como Frontera Simbólica. Ciencias Sociales 111-112: 143-54. Available online.

---. 2007. Más allá de las fronteras: Accesibilidad de niños, niñas y adolescentes nicaragüenses a la educación primaria en Costa Rica. Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos 33-34: 153-81. Available online.

Ramos, Alberto Cortés. 2006. Los imprescindibles migrantes nicas y la impresentable ley que los afectará. Revista Envíos Digital 289. Available online.

Ramos, Alberto Cortés and Adriana Fernández. 2020. ¿Cobertura universal? Las barreras en el acceso a la salud para la población refugiada nicaragüense en Costa Rica. Anuario del Centro de Investigación y Estudios Políticos (11): 257-89. Available online.

Regidor, Cindy. 2021. Migración nicaragüense seguirá en ascenso en 2021. Confidencial, October 3, 2021. Available online.

Salomon, Gisela and Claudia Torrens. 2021. With Turmoil at Home, More Nicaraguans Flee to the U.S. Associated Press, July 29, 2021. Available online.

Sandoval Garcia, Carlos. 2004. Contested Discourses on National Identity: Representing Nicaraguan Immigration to Costa Rica. Bulletin of Latin American Research 23 (4): 434-45. Available online.

---. 2014. Public Social Science at Work: Contesting Hostility Towards Nicaraguan Migrants in Costa Rica. In Migration, Gender and Social Justice: Perspectives on Human Insecurity, eds. Thanh-Dam Truong, Des Gasper, Jeff Handmaker, and Sylvia I. Bergh. Berlin: Springer. Available online.

---. 2019. Otros amenazantes: los nicaragüenses y la formación de identidades nacionales en Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial UCR. Available online.

Selee, Andrew, Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, Andrea Tanco, Luis Argueta, and Jessica Bolter. 2021. Laying the Foundation for Regional Cooperation: Migration Policy & Institutional Capacity in Mexico and Central America. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Semanario Universidad. 2021. Pandemia obliga a los nicaragüenses a una doble resistencia en Costa Rica. Semanario Universidad, March 3, 2021. Available online.

Solano-Campos, Ana. 2018. The Nicaraguan Diaspora in Costa Rica: Schools and the Disruption of Transnational Social Fields. Anthropology and Education Quarterly 50 (1): 48-65.

Sojo-Lara, Gloriana. 2015. Business as Usual? Regularizing Foreign Labor in Costa Rica. Migration Information Source, August 26, 2015. Available online.