The “Brain Gain” Race Begins with Foreign Students

The United States is considered a magnet for foreign talent. As cited in a report by the Institute of International Education (IIE), more than one-third of Nobel laureates from the United States are immigrants, and there are 62 patent applications for every 100 foreign PhD graduates in science and engineering (S&E) programs.

Foreign students make the United States one of the most profitable educational destinations. For example, according to NAFSA: Association of International Educators, foreign students and their dependents contributed more than $13 billion to the U.S. economy in 2004-2005. In addition, they enrich the cultural diversity and educational experience for U.S.-born students and enhance the reputation of U.S. universities as world-class learning and research institutions.

However, as the global competition for professionals, information technology (IT) workers, doctors and nurses, and university students and researchers intensifies, will the United States remain in the forefront in attracting the best and the brightest?

Foreign Students and Scholars in the United States: Yesterday and Today

The United States has been a destination for education and research for generations of foreign students and scholars, and this remains true today.

Graduate and undergraduate students have been coming to the United States to study science and medicine since the mid-1950s. Later, these students were joined by those interested in studying, researching, and obtaining practical training in computer and telecommunication sciences, business, education, law, social sciences, and the humanities.

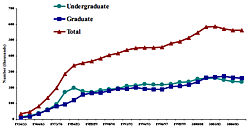

According to a recent Open Doors report by IIE, the number of international students has increased from 34,000 in 1954-1955 to almost 565,000 in 2005-2006. The share of foreign students as a percentage of the total student population rose as well, from 1.4 percent of total U.S. student enrollment in 1954-1955 to 3.9 percent in 2005-2006.

In 2000, of all skilled immigrants living within the 30 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), about half lived in the United States. Almost 22 percent of the 2.7 million foreign students who studied abroad in 2004 chose to attend university in the United States.

|

| To view the full-size version of Figure 1, entitled "Total, Undergraduate, and Graduate Enrollment of Foreign Students (in thousands): 1954-1955 to 2005-2006," click here. |

As Figure 1 demonstrates, the enrollment of total foreign and foreign graduate students has been rising steadily for the last five decades.

However, Figure 1 also shows that in the 2002-2003 academic year (a year after the terrorist attacks of September 11), the enrollment numbers of undergraduate students dropped by 0.4 percent and then by 4.6 percent a year later. The enrollment of graduate students continued to rise slowly but then dropped 3.6 percent in 2004-2005. In both cases, however, the rate of decline slowed down by 2005-2006. Moreover, the number of new foreign students enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities increased from 132,000 in 2004-2005 to 143,000 in 2005-2006, or by 8.3 percent.

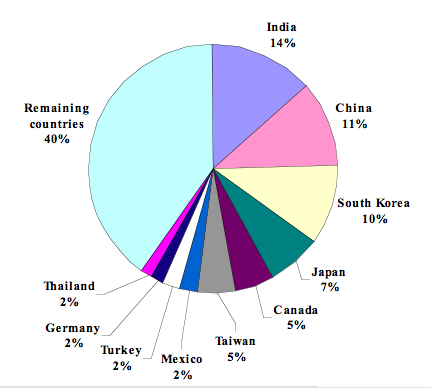

As in the past, today students from all around the world come to the United States to pursue their education dreams. Yet, just 10 countries — India, China, South Korea, Japan, Canada, Taiwan, Mexico, Turkey, Germany, and Thailand —accounted for 59.5 percent of all foreign students enrolled in 2005-2006 (see Figure 2).

|

|

||

|

In 2005-2006, almost one-third of all foreign students were enrolled in science and engineering (S&E) programs, while nearly one in six studied business and management, and one in 10 studied social sciences and the humanities (see Table 1).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Foreigners pursuing opportunities in U.S. education come to the United States not only to study but also to teach and do research. IIE reports that nearly 96,900 foreign scholars taught and engaged in research in 2005-2006 (foreign scholars are defined as nonimmigrant, nonstudent academics, such as teachers or researchers, who arrive on J-1, H-1B, O-1, or TN temporary visas). The number of foreign scholars in 2005-2006 increased 8 percent from 2004-2005 (89,600) and 63 percent from 1995-1996 (59,400).

China — the source of 19.6 percent of all foreign scholars in the United States — was the leading country of origin. Together with South Korea (9.2 percent), India (9.1 percent), Japan (5.8 percent), and Germany (5.3 percent), these five countries accounted for more than half of all foreign scholars in the United States, according to IIE.

In terms of major fields of specialization, life/biological sciences accounted for 23.2 percent of all foreign scholars, closely followed by health sciences (20.2 percent). These two fields are followed by physical sciences and engineering with 12.1 percent and 11.4 percent of all foreign scholars, respectively.

Challenges to America's Leadership

Nowadays the United States is not the only country in the world seeking to attract the best and the brightest.

On the global education market, while the United States receives the largest absolute number of foreign students, its share dropped from 25.3 percent of all foreign students studying abroad in 2000 to 21.6 percent in 2004.

At the same time, the share of other countries, such as New Zealand, Australia, Japan, and France, increased. For example, the share of New Zealand rose from 0.4 percent in 2000 to 2.4 percent 2004. This increase is significant given the size of New Zealand's student population compared with that of the United States.

Post-9/11 Effects: Reality and Perception

Why has the United States become less dominant? The first reason is directly related to tightened visa procedures and entry conditions for international students (especially for those from the Middle East) after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. For example, estimates by the Migration Policy Institute show that the annual number of F-1 foreign student applications submitted between 2001 and 2004 dropped by nearly 100,000. The total enrollments number fell as well, with decreases being more pronounced among many Gulf region countries, North Africa, and some Southeast Asian countries.

There is also evidence that students from these regions are increasingly choosing to study in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Oceania rather than in the United States. Although it is difficult to quantify, the atmosphere of heightened national security and restrictive visa processes undoubtedly has affected the perception some prospective foreign students have about the United States. Perhaps such students, thinking that the United States no longer welcomes them, have chosen to postpone their studies or go somewhere else altogether.

These trends prompted education experts and organizations such as NAFSA: Association of International Educators, the Council of Graduate Schools, and IIE, to name a few, to act swiftly and apply pressure on members of Congress and government officials to not lump together security risks and well-intended foreign students and researchers. These organizations argued that, while safeguarding the country from terrorists who might abuse the immigration system is crucial, the United States cannot afford to treat everyone as a threat.

Since then, the Department of State and U.S. embassies abroad have gone a long way to streamline interview and visa processes. In addition, colleges and universities have worked hard to reassure foreign students and scholars they are welcome. The measures have included expansion of recruitment efforts abroad, improvement of the infrastructure and informational support on campuses, and financial assistance to offset admission and tuition costs.

Yet, as pointed out by a 2006 NAFSA report, "Restoring U.S. competitiveness will require a concerted strategy, involving many agencies as well as higher education itself, to make the United States a more attractive destination for international students and scholars both in word and in deed."

More Competition

The second reason the United States has seen its share become smaller: aggressive recruitment efforts by Australia, New Zealand, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom, among others, that coincided with post-9/11 confusion over U.S. visa policies. These countries have used a combination of American-style programs taught in English and free or subsidized tuitions to attract foreign students. Also important, they have eased routes for permanent immigration after graduation in efforts to attract foreign students.

As English becomes a universal language not only in business but also in education, institutions in many non-English speaking countries — Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands, Germany, and Hungary — offer programs, especially in sciences and engineering, in English. Studying in Europe has always been less expensive than in the United States, Australia, or Canada, and many foreign students are taking advantage of the lower tuition fees and cost of living.

Similarly, non-Western countries, such as Singapore, Qatar, and Malaysia, use creative recruiting programs to become important regional players in international education as well as to use foreign students as generators of income revenue. For example, Singapore offers incentives and subsidiaries for well-known universities, such as MIT and John Hopkins, to establish their campuses in the country.

In the last couple of years, Canada and Australia — the traditional U.S. competitors for foreign students — started using their immigration systems as leverage to attract and retain highly educated persons.

Australia made it easier in 1999 for eligible foreign graduates of Australian universities to adjust to permanent resident status through its point system. Such applicants for permanent immigration also receive extra points for having a local degree. Furthermore, unlike in the past, in 2001 foreign students were allowed to apply for permanent residency without having to first leave Australia.

According to Australia's Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, about 8,000 permanent resident permits were issued to former students in 2002-2003 under Australian's Independent Skilled visa subclass (which is one of the three major visa classes under the General Skilled Migration Program; the other two are Australian Sponsored and State Specific/Regional Sponsored). This number doubled to about 16,000 by 2004-2005.

In fact, among 24,804 principal applicants approved in the Independent Migrant visa category, former foreign students accounted for 52 percent (12,978) in 2004-2005. In addition, eligible foreign graduates of Australian universities can apply after graduation for a Temporary Business (long-stay) visa, which is valid for up to four years.

Since April 2006, Canada has allowed eligible foreign students to work off-campus to offset tuition fees and participate in the Canadian economy. Also, spouses and common-law partners of full-time foreign students are allowed to apply for a work permit.

In 2005, the Canadian government sweetened its post-graduate work program for foreign graduates who agree to relocate and work outside of its three greater metropolitan areas — Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver. Their stay can be extended from one to two years.

European nations have taken notice of the success of foreign-student-friendly programs. In 2006, France softened its immigration policies to stimulate the inflow and post-graduation stay of its foreign students (read more in France's New Law: Control Immigration Flows, Court the Highly Skilled).

The United Kingdom leads Europe in terms of attracting skilled foreigners, including foreign students. More than 300,000 foreign students were enrolled in UK colleges and universities in 2004, accounting for 11 percent of all foreign students studying abroad.

Students from the European Economic Area (EEA) and Switzerland are allowed to live, study, work, and gain permanent residency with few hurdles anywhere in the UK. But all foreign students receive a student permit for the entire duration of their studies plus four months during which they can seek and take up employment with no work permit. Students also can bring their dependents, who are allowed to work.

Two schemes — the Science and Engineering Graduates Scheme (SEGS) and the Fresh Talent: Working in Scotland Scheme (FTWISS) — were introduced in 2004-2005 to retain non-EEA foreign students in the United Kingdom after graduation.

Under SEGS, foreign students with a graduate degree in any field, and foreign students with an undergraduate degree in physics, math, or engineering, can stay in the UK for up to 12 months to engage in any employment (including self-employment). They are further allowed to apply for permanent residency under one of the four skilled-labor schemes.

FTWISS aims to encourage non-EEA students to settle in Scotland by allowing eligible foreign students to work for up to two years with no work permit from the Home Office. Similar to SEGS participants, they are allowed to apply for a permanent residence permit under existing skilled-labor schemes.

In contrast, the United States offers no direct path to permanent immigration for foreign students unless they get sponsored by a U.S. employer or a U.S.-citizen spouse. Furthermore, the optional practical training (OPT) in the United States is currently set to be no longer than 12 months regardless of the type of work or level of degree obtained.

Also, with few exceptions, neither foreign students nor their spouses in the United States are allowed to work off-campus (foreign students on F-1 visas may be permitted to work off-campus while they study only if they can prove financial hardship).

China and India: Keep Them at Home

As described earlier, China and India together account for 25 percent of all foreign students enrolled in colleges and universities and about 28 percent of all international scholars in the United States. However, today China and India commit significant resources to boosting their own innovation and educational capacities. These investments are certainly timely efforts to meet the educational needs of their quickly growing populations and aid their economic development.

A 2005 New York Times article reports that China has increased its state funding for higher education from $4 billion in 1998 to more than $10 billion in 2003, and has experienced almost a fivefold increase in the number of students who completed their undergraduate and graduate studies. India has made substantial investments in its own higher education by pulling resources from public and private (domestic and international) sources.

Both China and India are tapping heavily into the scientific and business networks of their diasporas in the United States, Europe, Australia, and Canada. Attractive opportunities in the domestic educational system, as well as the promise of well-paid jobs and high socioeconomic status in the countries' emerging economies, are great incentives for bright young Chinese and Indian nationals to stay home.

As Anandraj Sengupta, a graduate of India's prestigious Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), told BusinessWeek in 2003, "We work in world-class companies, we're growing, and it's exciting. The opportunities exist here in India."

Conclusion

The race for foreign students is likely to intensify in the near future. A number of factors influence students' choice of where to study. Language of instruction, the reputation of a country's education system, availability of scholarships and financial support to offset tuition fees and cost of living, a welcoming environment, and post-graduation opportunities are just a few of them.

Given the internationalization of higher education and increasing competition for foreign talent, the United States will need to play to its strengths and be flexible enough to adjust its course of action when needed.

A version of this article first appeared as an Immigration Policy IN FOCUS paper, published by the Immigration Policy Center (IPC) in September 2006. Available online.

Sources

Bean, Frank D. and Susan K. Brown. 2005. "A Canary in the Mineshaft? International Graduate Enrollments in Science and Engineering in the United States." Presented at A Leadership Forum on International Graduate Students in Science and Engineering and International Scientists and Engineers: A National Need and a National Opportunity. Irvine, CA: University of California Irvine, Merage Foundations, and National Academies of Sciences.

Borjas, George J. 2004. "Do Foreign Students Crowd out Native Students from Graduate Programs?" National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online.

Borjas, George J. 2005. "The Labor Market Impact of High-Skill Immigration." National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online.

Birrel, Bob, Lesleyanne Hawthorne, and Sue Richardson. 2006. "Evaluation of the General Skilled Migration Categories." Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2006. "Off-Campus Work Permit Program Launched." Ottawa, Canada. Available online.

French, Howard F. 2005. "China Luring Scholars to Make Universities Great." New York Times. October 28.

Institute of International Education. 2006. "Open Doors 2006 Fast Facts." New York, NY: Institute of International Education. Available online.

Kripalani, Manjeet, Pete Engardio, and Steve Hamm. 2003. "The Rise of India." BusinessWeek. December 8. Available online.

Lowell, B. Lindsay. 2005. "Foreign Student Adjustment to Permanent Status in the United States." Presented at The International Metropolis Conference. Toronto, Canada.

NAFSA. 2005. "Dialogue, Not Monologue: International Educational Exchange and Public Diplomacy."

NAFSA. 2006. "Restoring U.S. Competitiveness for International Students and Scholars." Available online.

National Academies. 2005a. "Policy Implications of International Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Scholars in the United States." Washington, DC: Committee on Policy Implications of International Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Scholars in the United States, Board on Higher Education and Workforce, National Research Council. Available online.

National Academies. 2005b. "Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future." Washington, DC: The National Academies. Available online.

The Economist. 2005. "The Brains Business: A Survey of Higher Education." September 10th-16th.

Washington Post. 2006. "Foreigners Returning to U.S. Schools." Pp. A02.

Yale-Loehr, Stephen, Demetrios Papademetriou, and Betsy Cooper. 2005. "Secure Borders, Open Doors: Visa Procedures in the Post-September 11 Era." Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.