You are here

Imminent End of Formal U.S. Pandemic Emergencies Marks New Era in Immigration Realm

President Joe Biden in the White House. (Photo: Adam Schultz/White House)

The looming termination of the U.S. public-health emergency designation imposed at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic will usher in sweeping changes that touch many facets of life in the United States, including for people arriving at U.S. borders and immigrants residing in the country. The lifting of the emergency declaration, set to occur on May 11, could end COVID-19 vaccine requirements for international visitors and end the summary expulsion of asylum seekers and other migrants at the U.S. border under Title 42, although many will face a new set of rules for seeking asylum. It will also affect access to free COVID-19 vaccines, testing, and treatment; end expanded food assistance to some low-income individuals; and coincide with changes that cause millions to lose Medicaid coverage. While these impacts will hit all U.S. residents, they will have a disproportionate impact on immigrants, especially those with low incomes.

Some of the fallout from terminating the emergency declaration and two related national emergencies will occur gradually. Expanded access to public benefits such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and expanded Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) allotments were originally tied to the emergency declaration, but with the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 Congress mandated that they begin winding down in March and April, ending by May 2024. Other critical federal relief introduced during the pandemic has either already ended or is not linked to the emergency declarations and thus will remain in effect. This includes stimulus payments, enhanced unemployment benefits, bans on evictions, emergency rental assistance, and expanded subsidies for health insurance purchased through a marketplace. Similarly, supplemental state and local assistance in some cases may not be tied to the ending of federal emergency designations.

Many pandemic-era safety net benefits yielded tremendous results, including a record drop in poverty, and offset some of the economic challenges of the pandemic, which were disproportionately borne by immigrants and those in mixed-status families. Meanwhile at the U.S.-Mexico border, authorities have expelled migrants more than 2.6 million times under Title 42, depriving many of an opportunity to seek asylum in the United States and contributing to a haphazard and ad hoc treatment of border arrivals. The end of the public-health emergency declaration, then, marks the transition to an uncertain new period.

At the same time, hundreds of U.S. residents are dying daily of COVID-19 and the World Health Organization (WHO) still considers the disease a public-health emergency of international concern. But the pandemic has reached an inflection point, according to WHO; high rates of immunity are limiting the disease’s impact and long-term public-health attention should transition to mitigating the impacts of the virus, which is now endemic. All 50 U.S. states and Washington, DC declared public-health emergencies at the start of the pandemic; only seven are set to continue past February.

This article outlines the possible changes facing immigrants and new arrivals to the United States because of the lifting of the federal public-health emergency designation in May.

Border Expulsions May Be Replaced by a New Asylum Regime

The starkest change on the immigration front may be at the U.S.-Mexico border, where the Biden administration has claimed it will end controversial expulsions of unauthorized migrants that began in March 2020, when the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an order under Title 42 of the Public Health Services Act. Initially applied primarily to Mexican and Central American migrants, Title 42 was recently expanded to expel substantial numbers of Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans; at the same time, the administration also opened a parole program for some arriving with advance notice. Although ongoing and complex litigation raises uncertainty about whether expulsions will actually halt on May 11, this date is likely to mark a new chapter for Title 42.

Linked to the potential end of the expulsions order, the government on February 21 announced it would issue a proposed rule that fundamentally alters the border asylum process by incentivizing asylum seekers to schedule appointments at ports of entry using an app. Those who do so will be screened for asylum under the traditional process. Those arriving between ports of entry will be presumed to be ineligible for asylum if they came through a transit country without applying for asylum there. The differentiated treatment will make it much harder for people who enter the country without authorization to obtain asylum.

The Saga of Title 42

The story of Title 42 is long. First implemented in March 2020, the order has been updated several times, most recently in August 2021. That version states the order will remain in effect until either the end of the public-health emergency or CDC’s determination that the introduction or spread of COVID-19 is no longer a serious danger to public health.

In April 2022, the agency exercised the second option, issuing a Federal Register notice terminating the order effective May 23, 2022. However, a group of Republican-led states quickly sued to keep Title 42 in place; in Louisiana v. CDC, a federal court in Louisiana issued a preliminary injunction, finding in favor of the states on the basis that the Biden administration did not follow the notice-and-comment requirement of the Administrative Procedures Act. The administration appealed that decision to the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, where the case is paused until at least May 11.

Meanwhile, in a separate case, Huisha-Huisha v. Mayorkas, a federal judge in Washington, DC deemed Title 42 expulsions to be unlawful. The GOP-led states involved in the Louisiana case sought to intervene in this litigation to defend the continued use of expulsions, but district and appellate courts ruled against their intervention, prompting an appeal to the Supreme Court. Oral arguments on the states’ attempt to intervene were scheduled for March 1, but were taken off the calendar last week.

As a result, barring additional court action, Title 42 will continue until at least May 11. The administration has argued that the imminent end of the public-health emergency will automatically terminate the Title 42 order on that date, thus rendering the Louisiana and Washington, DC cases moot. The challenging states disagree, arguing that the underlying questions remain valid and that Title 42 should remain in place.

The path forward on litigation is murky, given that there are now cases before the Fifth Circuit and the Supreme Court. They raise different legal issues, but if either court accepts the government’s argument that the cases are moot in light of the end of the public-health emergency, Title 42 will end. If both courts do not accept that argument, proceedings will continue, with Republican-led states likely arguing the end of the public-health emergency does not automatically allow the administration to terminate Title 42, at least not without going through a formal regulatory process. More appeals could follow.

Yet it may not be the courtroom where Title 42’s fate is determined. Congress may intervene to adopt something akin to Title 42 on grounds unrelated to the public-health declaration. This option seems more possible with the new Republican House majority and with support for Title 42 from some moderate Democrats.

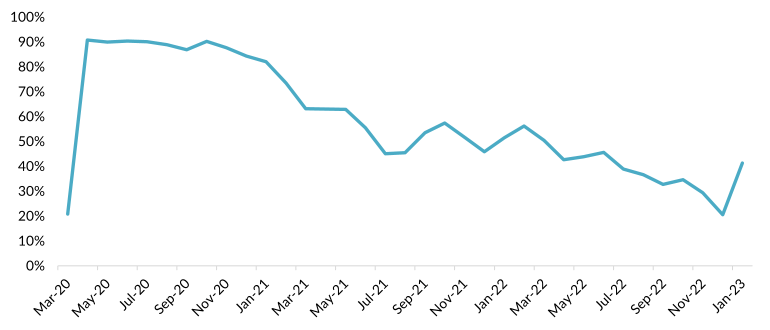

In practice, use of Title 42 has been on an overall decline. Since early 2020, a shrinking share of migrant encounters have resulted in expulsion, due to multiple exceptions to the policy and Mexico’s willingness to accept only certain nationals. In December, authorities relied on Title 42 for just one-fifth of encounters, though this percentage ticked up in January as Cubans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans were subjected to the policy and overall border encounters fell.

Figure 1. Share of Migrant Encounters at the U.S. Southwest Border Resulting in Title 42 Expulsions, 2020-23

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Nationwide Encounters,” updated February 6, 2023, available online.

What Is Next? Border Policies Post-Title 42

Before the Title 42 order and especially before the Trump administration took office, regular order at the border meant migrants intercepted crossing without authorization faced one of several outcomes. Many were placed into expedited removal proceedings, which led to quick removals of those who could not show in an interview that they face a credible fear of persecution in their origin country. Those who passed credible fear interviews could seek asylum before an immigration judge. Alternatively, migrants with a prior removal order saw that order reinstated, also leading to quick returns. Some migrants agreed to voluntarily return to Mexico. A relatively small share was placed into removal proceedings and either detained or released into the United States pending an immigration court hearing, the latter an outcome usually prompted by resource constraints. Some migrants were charged with the federal crimes of illegal entry or re-entry. These outcomes bring penalties such as bars to re-entering the country, unlike Title 42, whose lack of sanctions has incentivized many to attempt re-entry after expulsion. Unlike Title 42, all these scenarios allow for screening for humanitarian protection. And none resulted in migrants—other than Mexicans—being forced back into dangerous border cities, where kidnappings and violence have been common.

The administration has signaled it will not revert to regular order post-Title 42, but will rely on a new asylum regime at the Southwest border. For the moment, it has told migrants to use a smartphone app called CBP One to make an appointment at a legal border crossing to request entry into the United States as an exception to Title 42. However, appointments are very limited, leaving many migrants unable to secure a slot, and users have encountered multiple problems with the app.

As announced in the proposed rule issued this week and which the administration intends to finalize by May 11, the app-based appointment process will be the main way for migrants to seek asylum post-Title 42; officials plan to make more appointments available. Under the proposal, those who arrive without an advance appointment and who did not seek asylum in countries they passed through on the way to the United States will face a rebuttable presumption of ineligibility for asylum. As a result, those put into expedited removal—who are mainly single adults—will be less likely to pass fear screenings. And those allowed into the country to seek asylum will be less likely to secure it, though they may be eligible for lesser protections, such as withholding of removal and relief under the Convention against Torture, that do not open a path to permanent residence. Unaccompanied children would be exempt from the new standards.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has also opened new parole programs for approved migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela who have a U.S. financial sponsor, hold a valid passport, and purchase a plane ticket. The parole programs were designed to take pressure off the border. In January, more than 11,600 migrants entered through the new programs. Some Republican-led states have questioned the legality of the programs, which could spell a long court process.

Furthermore, the administration is also reportedly talking with Mexico about removing inadmissible non-Mexicans to Mexico, rather than sending them to their origin country. And officials have told reporters they are working on a bill to drastically reshape asylum law and implement border processing centers, though such legislation is unlikely to pass Congress in the near future. Altogether, these plans raise important and unresolved questions about what border processing and access to asylum will look like in a post-Title 42 world.

Vaccine Requirement Will Be Re-Evaluated

The United States has been a holdout among Western countries in maintaining a requirement that most adult travelers to the country be vaccinated against COVID-19. Most European countries had halted the requirement by mid-2022, Australia did so in July, and Canada in October. Internationally, most countries that have upheld vaccine requirements allow unvaccinated travelers entry if they submit a negative COVID-19 test.

Although the U.S. requirement is not formally linked to the COVID-19 emergencies, it may soon be dropped. Under pressure from Congress, the administration has said it will review the requirement as part of preparations for the end of the emergency declaration.

Changes to Public Benefits

It may not be felt immediately, but one of the most profound long-term impacts of the post-pandemic era will be reduced access to public benefits for some, immigrants included. In declaring a national emergency on March 13, 2020, President Donald Trump relied on two authorities—the National Emergencies Act and the Stafford Act—which combined allowed the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to broaden CHIP, Medicaid, and Medicare requirements; among other changes, he also authorized the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to provide assistance. That March, Congress also authorized additional relief, including requiring that states maintain continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees in exchange for the federal government covering a larger share of Medicaid costs. (Medicaid eligibility is normally redetermined at least annually, with those found to be no longer eligible removed from the rolls.) As a result, Medicaid enrollment grew by 20 million people over the course of the pandemic. Congress also lifted three-month limits on accessing SNAP for many unemployed adults without disabilities or dependents; expanded SNAP to more students; and allowed states to boost SNAP benefits to participating families.

Medicaid, CHIP, and SNAP are available to naturalized U.S. citizens as well as lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green-card holders) who have held their status for at least five years. Refugees, asylees, and some other humanitarian migrants are also eligible for Medicaid, CHIP, and SNAP without a five-year wait. LPR children and pregnant women are eligible for Medicaid without a five-year wait in some states that have expanded coverage, as are some pregnant women and children who hold liminal statuses, for example those with Temporary Protected Status or who are asylum seekers. LPR children are eligible for SNAP without a five-year wait.

Medicaid Rolls to Shrink

States can begin disenrolling recipients from Medicaid, the public health insurance program largely for people with low incomes, who are determined to no longer be eligible starting this April, and must complete the reverification process by May 2024, as Congress in December ordered when it delinked Medicaid continuous coverage from the public-health emergency. Extra federal Medicaid funds will wind down by December. Millions of people will lose Medicaid coverage during this reverification process (HHS estimates 15 million people will lose coverage, while the Kaiser Family Foundation puts the estimate between 5 million and 14 million), and a disproportionate number will be Black and Latino. By the federal government’s estimates, nearly 7 million of those losing coverage will remain Medicaid-eligible but will struggle to complete the reverification process.

Low-income immigrants are particularly likely to fall through the cracks of reverification. States’ patchy outreach in languages other than English may create barriers for immigrants with limited English literacy. Immigrants experience higher rates of residential instability, which can mean missing renewal forms and other paperwork arriving via mail. Some noncitizens may fear that providing information to the government will put their legal status in jeopardy, even if they previously provided the information years ago. Or they may have been working informally, making it difficult to document their income eligibility.

However, some new Medicaid provisions affecting immigrants and U.S.-born families alike will not change as the public-health emergency wanes. Congress required that starting next year, states must keep children enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP for a year at a time without reverification, which can prevent eligible children from losing coverage due to re-enrollment barriers. Congress also made 12 months of postpartum care—originally available only through 2027—a permanent state option.

Emergency SNAP Allotments Ending

SNAP benefits are electronic payments that vary by income and household size and can be used to purchase groceries. So-called emergency allotments authorized by Congress in March 2020 increased benefits up to the maximum allowed for a household of a given size or by a minimum of $95. They were originally tied to the federal public-health emergency and a state’s emergency declaration, but lawmakers have delinked the benefits and the last payments under the program were issued in mid-February. While all states initially offered the emergency allotments, 18 had already stopped before this month.

Reductions in benefits will particularly affect low-income mixed-status immigrant families, where only some members are U.S. citizens and eligible for SNAP. In such households, SNAP benefits are prorated to the number of eligible household members, so lower amounts must be distributed among more individuals.

Some additional changes to the SNAP program, affecting immigrants and the U.S. born alike, are tied to the end of the public-health emergency. In pre-pandemic times, non-elderly adults (under age 50) without disabilities or dependents were limited to three months of SNAP benefits in any three-year period, unless they worked or participated in a work program. These time limits were suspended during the pandemic but will return starting in June, after the end of the public-health emergency. Also, some students, including some foreign-born students, became newly eligible for SNAP during the pandemic if they came from low-income families or were eligible to participate in state or federally financed work-study; this expanded eligibility will also end in June, after the end of the public-health emergency.

Pandemic EBT to Transition to Summer Program

During the pandemic, Congress created the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program so that children who were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch in school or day care could access nutritional assistance even when schools were closed. Families received electronic benefit cards that they could use for groceries in lieu of the free meals. Like the school lunch program, P-EBT is available regardless of immigration status.

P-EBT was initially set to be available only for only the duration of the public-health emergency, but Congress has extended it through this summer, while also establishing a permanent summer EBT program. Starting in 2024, the new program will provide families at least $40 per month per eligible child over the summer.

Access to Testing, Vaccines, and Treatment Could Change

During the pandemic emergencies, the federal government extended broad access to COVID-19 vaccines, testing, and treatment to many people without health insurance, who are disproportionately immigrants, and often even to those without lawful status. Once the public-health declaration winds down, COVID-19-related care will largely be treated like other health care, with access varying widely depending on insurance coverage and type. Immigrants without insurance, including those ineligible for public health insurance, may face the largest out-of-pocket costs for COVID-19-related care.

Fewer Free Tests

Currently, individuals with private insurance or Medicare are eligible for up to eight free at-home tests per month. This will end with the sunset of the pandemic emergency unless private insurers opt to continue coverage. Medicaid beneficiaries will continue to have access to free at-home tests through September 2024. Most uninsured individuals have not had free access to testing under federal policies, although some may have been able to secure tests through local clinics, libraries, and other institutions. Nothing will change for them when the emergency ends.

Tests at doctors’ offices, which are free for those with Medicare and private insurance, may require co-pays after the declaration ends. People on Medicaid will continue to have free in-office tests through September 2024. Uninsured individuals will continue to face costs for in-person tests unless they can find free testing through a health center or other location.

Vaccines to Remain Free for Many

Vaccines will remain free for those with Medicare and Medicaid, and will remain free in-network for those with private insurance. Uninsured individuals will continue to have access to free vaccines as long as there is a supply of federally purchased vaccines. After that stock ends, Moderna has pledged to offer its vaccines for free after the public-health emergency ends; uninsured people may have to pay a market price for vaccines from other manufacturers. A separate federal program, Vaccines for Children, covers vaccines for uninsured children generally and will also cover COVID-19 vaccination.

Treatment Costs May Change

Costs of antivirals, monoclonal antibodies, or other COVID-19 treatments may change with the end of the emergency, but only when current federal supplies are exhausted. Patients with Medicare or private insurance may face new co-pays for drugs to treat COVID-19 (although those with Medicare Part D can get free Paxlovid through December 2024), while Medicaid enrollees will continue to access treatments without cost until September 2024. Uninsured individuals will need to pay a market price.

Moving into the New Normal

The imminent end of the public-health emergency will bring some concrete changes to U.S. policy, with implications for arriving migrants and immigrants already living in the United States. But many pandemic-era policies and supports have already wound down or are in the process of doing so. As such, the end of the emergency also serves as a symbolic marker of the country’s transition from crisis response to a new normal in which COVID-19 will be treated like any other public-health issue.

Access to COVID-19-related care will soon look much like all other health-care challenges, with quality insurance necessary for affordable care. This return to normal disadvantages immigrants, who are less likely to have employer-provided health insurance and less likely to be eligible for public insurance. As a whole, 19 percent of immigrants in the United States lack health insurance, compared to 7 percent of U.S. born, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Public-benefit policies will largely return to their pre-pandemic state, but there will be some meaningful and positive changes. Longer Medicaid coverage periods for children, longer availability of postnatal care, and permanent summer EBT payments for student participating in free or reduced school lunches will continue to serve as important supports for the wellbeing of low-income families with children, whether immigrant or U.S.-born. Indeed, the emergency may have triggered some important permanent reforms to these programs.

At the U.S.-Mexico border, the treatment of migrants post-Title 42 may look very different than before. Seeking to blend policies that discourage irregular migration with legal pathways and protection for those who follow new rules, the administration appears poised to advance a number of approaches. The precise form of these policies and whether they will bring order to the border and provide access to asylum for qualifying migrants fairly and efficiently remains to be seen.

The impact of the last three years cannot be overstated. Millions of expulsions have contributed to disarray at the border and deprived many asylum seekers of their chance to seek protection. Meanwhile, expanded public benefits and COVID-19-related health care have had major impacts on U.S. residents of all types, including many low-income immigrants. While the country enters a new era, the reverberations of this period will continue to be felt.

The authors thank Kathleen Bush-Joseph, Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh, and Caitlin Davis for their research assistance.

Sources

Bendix, Aria. 2023. Costs for Covid Tests and Treatments May Rise after Federal Emergency Declarations End in May. NBC News, January 31, 2023. Available online.

Butash, Charlotte. 2020. What’s in Trump’s National Emergency Announcement on COVID-19? Lawfare, March 14, 2020. Available online.

Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS) and Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). 2022. Preparing for the End of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency: Opportunities to Support Medicaid and SNAP Unwinding Efforts. Presentation, November 3, 2022. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Jessica Bolter. 2022. Controversial U.S. Title 42 Expulsions Policy Is Coming to an End, Bringing New Border Challenges. Migration Information Source, March 31, 2022. Available online.

Cox, Cynthia, Jennifer Kates, Juliette Cubanski, and Jennifer Tolbert. 2023. The End of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency: Details on Health Coverage and Access. Kaiser Family Foundation, February 3, 2023. Available online.

D’Avanzo, Ben. 2023. End of Pandemic Medicaid Protections May Leave Many Immigrants without Health Insurance. National Immigration Law Center, February 7, 2023. Available online.

Food Research and Action Center (FRAC). N.d. Summer and Pandemic EBT Provisions in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023. Available online.

Lacarte, Valerie. 2022. Immigrant Children’s Medicaid and CHIP Access and Participation: A Data Profile. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Lacarte, Valerie, Mark Greenberg, and Randy Capps. 2021. Medicaid Access and Participation: A Data Profile of Eligible and Ineligible Immigrant Adults. Washington, DC: MPI, October 2021. Available online.

National Academy of State Health Policy. 2023. States’ COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Declarations. Updated February 6, 2023. Available online.

Park, Edwin, Anne Dwyer, Tricia Brooks, Maggie Clark, and Joan Alker. 2023. Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023: Medicaid and CHIP Provisions Explained. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families. Available online.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2022. Order Under Sections 362 & 365 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. §§ 265, 268) and 42 C.F.R. § 71.40: Public Health Determination and Order Regarding the Right to Introduce Certain Persons from Countries Where a Quarantinable Communicable Disease Exists. April 1, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Public Health Determination and Order Regarding Suspending the Right to Introduce Certain Persons from Countries Where a Quarantinable Communicable Disease Exists. Federal Register 87, no. 66 (April 6, 2022): 19941. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2023. CBP Releases January 2023 Monthly Operational Update. News release, February 10, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Fact Sheet: COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Transition Roadmap. Press release, February 9, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Preparedness and Response. 2023. Renewal of Determination that a Public Health Emergency Exists. January 11, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. A Public Health Emergency Declaration. Accessed February 10, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. 2022. Unwinding the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision: Projected Enrollment Effects and Policy Approaches. Issue Brief, August 19, 2022. Available online.

White House. 2020. Letter from President Donald J. Trump on Emergency Determination Under the Stafford Act. March 13, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Proclamation on Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. March 13, 2020. Available online.

Williams, Elizabeth, Robin Rudowitz, and Bradley Corallo. 2022. Fiscal and Enrollment Implications of Medicaid Continuous Coverage Requirement during and after the PHE Ends. Kaiser Family Foundation, May 10, 2022. Available online.

World Health Organization. 2023. Statement on the Fourteenth Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. News release, January 30, 2023. Available online.