You are here

Building Climate Resilience through Migration in Thailand

Residents are affected by massive flooding in Thailand in 2011. (Photo: Cpl. Robert J. Maurer/U.S. Marine Corps)

Thailand is particularly vulnerable to droughts and floods. The country has experienced a number of extreme-weather events in recent years, including severe flooding in 2011 that inundated Bangkok and large tracts of central Thailand for weeks, as well as an extended period of drought in 2015-16 that was the worst in decades.

These types of events affect the country as a whole, but rural, agrarian communities in the poor and dry Northeast region can be considered particularly lacking resilience to environmental changes. There is little evidence to date that climate or environmental factors clearly and directly prompt migration in the region, however environmental and especially climate risks play important roles in destabilizing rural agricultural livelihoods. These risks, in turn, increase the likelihood for some household members to migrate, as it becomes increasingly difficult to earn a living. This is a significant consideration, given that about 30 percent of the Thai workforce is employed in an agricultural sector dominated by small-scale family farms. Instead of merely serving as an escape route, migration can be a way for households to proactively guard against increasing effects of climate change on local environments and livelihoods.

Special Issue: Climate Change and Migration

This article is part of a special series about climate change and migration.

Worldwide, migration amid environmental change is discussed today primarily in the context of crises, conflicts, and humanitarian disasters, and is considered to be something negative that should be prevented. The phenomenon is regularly framed as a sign of failed adaptation, with migrants usually portrayed as passive victims. This narrative is often adopted by the media, politicians, and practitioners who frequently claim that anywhere from 300 million to 1.5 billion people could be forced to migrate by 2050 due to climate change.

However, the conversation is largely decoupled from state-of-the-art social science findings. There is widespread agreement in academia that these apocalyptic numbers of future “climate refugees” lack sound methodological and empirical basis and must be regarded as guesstimates at best. There is also a lack of recognition that migration itself, whether internal or international, can be a successful adaptation strategy. Furthermore, migration is a normal part of life for many people, with an estimated 272 million international migrants and more than 760 million internal migrants worldwide as of 2019. Environmental change, therefore, always occurs within a broader context of populations already migrating for one reason or another.

The crucial question, then, is under what circumstances does migration have the potential to generate positive effects for coping with and adapting to environmental change? This article, partly based on a 2019 policy brief for the German Federal Agency for Civic Education, offers perspectives from Thailand. It analyzes interactions between environmental change and migration and offers the notion of “translocal resilience” as a framework for evaluating how individuals, households, and communities can and do benefit from migration to offset some of the hazards of a changing environment.

Definitions

Climate change refers to variation in long-term regional and global temperature, humidity, and precipitation.

Environmental change or environmental degradation refers to changes on ecosystems and natural resources that can occur from climate change or human activities such as changing land use, pollution, or deforestation.

Translocality refers to the social, economic, and cultural connections and flows between people and places over distances; it emphasizes that migrants and their families or households at places of origin stay connected.

Success or Failure: The Many Facets of Mobility and Immobility in the Context of Climate Change

While environmental factors certainly influence peoples’ livelihoods and their decisions to migrate, migration in turn also influences how those exposed to climatic and environmental risks are able to cope with and adapt to them.

The case of Pom is illustrative (for privacy reasons, his name and those of all interviewees in this article are pseudonyms). In 1990, at age 19, he left his village in Northeast Thailand and moved to Singapore to find work and earn more money, following in his father’s footsteps. During his 21 years in Singapore, Pom returned only for brief visits to Thailand, never staying more than one or two months. He rose from construction worker to foreman and was able to eventually send the equivalent of 1,500 euros per month to his family in Thailand. While still working in Singapore, Pom used the money to buy additional agricultural land in his native village for his parents and his wife, as well as to build larger homesteads. Upon return, he also relied on the business acumen he developed abroad to realize various commercial ventures, including a pig farm and a karaoke bar.

Pom’s decision to migrate turned out to be a profitable one for him and his family, and it cut against the prevailing and longstanding perception of migration amid environmental risk as a last resort for ailing communities.

The Complexity of Migration

Numerous empirical studies show there is no direct, monocausal connection between environmental or climate change and migration. Human mobility is extremely complex, and the impact of environmental or climate change on migration is mediated through economic, social, and political processes. Thus, it is often very difficult to isolate how environmental factors contribute to individual migration decisions versus economic, social, or cultural reasons. At the same time, migration should be acknowledged as just one of the manifold livelihood strategies that households adopt to deal with stresses emerging from environmental change.

Against this background, analysts’ interpretation and assessment of mobility amid climate change can vary greatly. On the one hand, migration can be an indicator of a household or community’s failure or inability to deal with risks. For example, a drought can lead to the complete collapse of an agricultural system, suggesting the failure of coping strategies, such as use of granaries, and adaptation measures, such as developing alternative local sources of income. In this case, migration may be the last resort to ensure survival. On the other hand, as in Pom’s case, migration can itself be a successful adaptation. At the onset of drought, for instance, some households could send a member to work in the city; the urban worker then sends money back to the household to compensate for crop failures. In this case, migration would be successfully employed to manage a crisis.

It is important to note that not everyone who is affected by events such as drought needs to, wants to, or is able to migrate. Like migration, immobility cuts both ways. On the one hand, immobility can be a sign of great vulnerability and unsuccessful adaptation, such as when a household’s in-situ coping mechanisms fail but people lack the necessary skills and resources to move. On the other hand, immobility can also be a sign of resilience, such as for households able to cope with the effects of environmental stresses locally, with available resources. These households do not need to be mobile in order to ensure their survival.

These explanations show that neither mobility nor immobility in the context of climate change can per se be interpreted as success or failure. Instead of framing migration in these binary terms, it makes more sense to consider the degree of freedom that individuals and households have in deciding whether or not to migrate in order to improve their livelihood situation or to cope with or adapt to environmental change.

Conceptualizing the Contribution of Migration: From Migration as Adaptation to “Translocal Resilience”

The positive view of migration as a potentially successful way to deal with stress situations amid climate change has been increasingly recognized in academic and political debate, although this perspective receded somewhat following Europe’s migration and refugee crisis of 2015-16. To describe migration’s potential in this context, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) uses the phrase "migration as adaptation." Analysis revolves primarily around the role of remittances, in the form of financial remittances as well as the transfer of knowledge and ideas, and is centered on managing, facilitating, and regulating migration in the context of risks. This discussion makes an important contribution to balancing the widespread but one-sided, negative view of migration in the context of climate change.

The notion of “translocal resilience” offers a conceptual framework that does more justice to the complexity of the nexus of migration and climate change. It observes that, regardless of expected climatic change, migration is a global social phenomenon and will continue to be an important driver and aspect of global change. Migration, in other words, is not something extraordinary that only occurs in crisis situations, but is already an integral part of the lives and livelihoods of many people and households worldwide. A comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the environment and migration therefore requires a consideration of existing migration and translocal linkages, especially in the context of vulnerable livelihood systems. People’s everyday vulnerability—not only that brought about by extreme situations or in response to extraordinary events―and the potential role of migration in reducing it, is of central importance.

Most importantly, migration is not a process that begins with one’s departure from his or her region of origin and ends with arrival somewhere else. Migration connects people, changes places, enables the permanent exchange of knowledge and resources, and thus creates a networked translocal social space: a set of relations, flows, and identities that spans distances. It enables households to spatially and sectorally diversify their livelihood bases, in turn strengthening their ability to deal with climate-related risks and maintain or increase their economic and overall wellbeing.

Translocal resilience can therefore be defined as the ability of individuals, households, and communities to deal with stress and risks and to maintain or increase their wellbeing stemming from their translocal distribution, connections, and exchanges. Although this article’s focus is the ability to withstand shocks and hazards associated with climate change, the concept can also be applied to other sorts of risks.

A better understanding and, possibly, strengthening of this concept thus requires a focus on the interactions of the individuals, conditions, and connections that link migrants in places of destination and households at places of origin, including social and economic elements. Considering the structures of these constellations and the agencies of individuals involved helps to reveal and understand conditions of translocal resilience.

Strengthening Resilience through Translocal Relations: Practical Examples from Thailand

Translocal resilience therefore depends on the variety of characteristics of migrants at places of destination and households at places of origin, their multilevel embedding in social, economic, and other structures at their respective places, and the strength and dynamics of the relations and interactions between them. Examples from the authors’ field research in Thailand illustrate cases and mechanisms of translocal resilience, showing under which conditions migration can contribute to enhanced resilience against environmental risks.

As noted earlier, the authors could not find cases in Northeast Thailand in which migration could be directly attributed to climate change. Yet the changing climate contributes to destabilizing agricultural livelihoods, increasing the likelihood of migration by some family members. Thus, regardless of the immediate drivers, rural migration—both to other parts of Thailand and internationally—and the ensuing connections between migrants and their origin households can help the households enhance resilience against current and future environmental risks, for example through adaptation of agricultural production.

Characteristics of migrants and their origin households, their embedding in community and larger structures such as urban labor markets, and their relations and interactions with each other can lead to dramatically different outcomes. However, the authors have noted some general patterns, among them that the socioeconomic status of the household at the place of origin is highly influential. It affects whether there are the resources for migration, either internationally or internally; the migrant’s education and skills; and the household’s dependence on regular remittances, which affects what demands the migrants perceive.

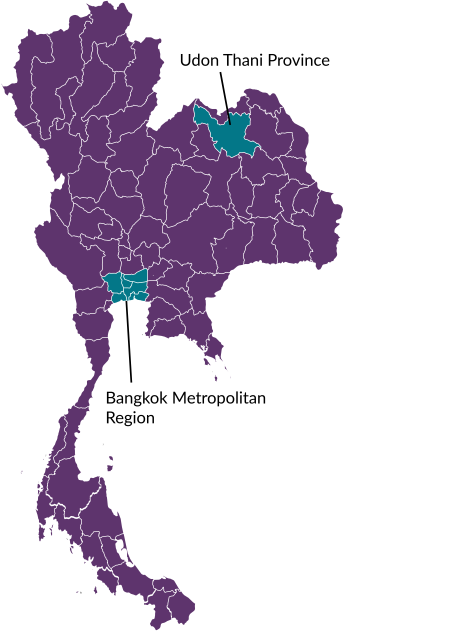

The precarity of migrants’ place-of-origin households are thus often mirrored in working and living conditions at destination. Lamai, a 42-year-old female internal migrant who worked in a garment factory in Bangkok when interviewed in 2015, came from a highly indebted, poor farming household that lacked income sources and depended on her remittances. She had come from Udon Thani province in the Northeast in the mid-1990s to earn additional income, as her family did not own enough land to secure a livelihood. Lamai also had to repay an informal, high-interest loan in the city that she took to pay down her family’s debts in the village. She could not afford to take any risks to improve her and her family’s situation and did not see any option other than continuing to make ends meet for both her urban and rural family. These kinds of situations tend to lead to stagnation instead of adaptation and improved livelihoods.

Figure 1. Map of Thailand

Inversely, the case of Phichit, a 40-year-old man who in 2015 worked as a technical supervisor at a Bangkok factory, shows how better resource endowment at the place of origin is associated with more positive development. Phichit came from a better-off rural farming household also in Udon Thani province and was able to finish secondary school before moving to Bangkok. As his household of origin did not depend on his remittances, he could save enough to afford a bachelor’s degree, in turn enabling him to obtain a better paid and permanent position at the factory. He invested in his parents’ farm, building ponds and acquiring livestock, and during visits was even able to help village associations organize development activities and write funding proposals to governmental and nongovernmental agencies.

Social and Financial Remittances Combined

The density and quality of migrants’ social relations depend on a range of factors, including generational and filial structures, gender relations, and the embedding and positionality in social and economic systems at their places of destination. For Thai laborers migrating to Singapore, for example, exclusionary and segregationist policies at destination can contribute to them retaining a strong orientation towards families and rural origin villages in Thailand.

Translocal interactions between migrants and their households of origin are epitomized in different types of remittances. In addition to financial transfers that can help sustain household income and buffer against losses, migrants may transmit social remittances in the form of ideas, skills, innovations, and changed perceptions of risks and opportunities, which play an important role in households’ resilience. Studying the experiences of these Thai migrants in Singapore, Simon Alexander Peth and Patrick Sakdapolrak show that a combination of financial and social remittances leads to livelihood transformation and changed practices, while financial remittances alone tend to maintain the status quo, and social remittances such as new ideas can often get “lost” without sufficient material support.

Pom, mentioned earlier in the article, represents one example of the successful strengthening of social resilience through a combination of financial and social remittances. The income and skills that he acquired through migration enabled him and his family to diversify their income base, making them less vulnerable to environmental and climatic risks.

However, in many cases migrants’ working conditions are so different from their places of origin that their skills, knowledge, and ideas cannot easily be transferred. This was the case with Thong, a 29-year-old return migrant from Northeast Thailand who worked in industrialized farming in Israel for five years. The drip irrigation scheme he operated in Israel depended on sophisticated computer technology; even with all the necessary technical skills to set up such a system in Thailand, he simply could not afford the technology and hardware.

Implications for Policy

This analysis shows that migration can and does contribute to increased resilience that can be beneficial in the event that migrants’ households are exposed to greater climate risks. The extent to which that is the case depends on a number of conditions and factors both at origin and destination, most of which offer entry points for policy action beyond traditional migration management. Among these factors are the socioeconomic situations of households of origin and migrants’ ability to send financial remittances and gain knowledge, skills, and ideas to better cope with or adapt to risk. As one example of possible policy moves, rural and agricultural development organizations could offer investment training to households with migrants, remotely involve absentee migrants in local activities and community development strategies, or view return migrants as potential agents of change and offer appropriate financial or organizational support.

Whether migrants can send both financial and social remittances to a significant extent also depends on a range of policy areas. Migration policy certainly plays a role here, especially for international migration, as legal barriers drive the financial and organizational costs that can be decisive for an individual’s ability to migrate. But other policy fields are also highly relevant, shaping for example migrants’ working conditions, payment and social insurance schemes, health care, housing conditions, and education for them and their children. It is important to also acknowledge the special vulnerabilities of migrants on their journey and often also at destination.

The debate on environmental migration should aim to strengthen the capacity of vulnerable people to adapt and increase their freedom to decide whether to move or stay. However, this seems difficult at present, given the polarization around migration in many parts of the world. On the one hand, the environment-migration nexus has become a topic of concern in recent years and was mentioned in the United Nations-backed Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration. On the other hand, the policy debate in a number of countries has been increasingly dominated by nationalistic sentiments. Together with COVID-19-related mobility restrictions, it remains an open question whether wealthy countries such as the United States or those in Europe would engage in discourses to welcome immigrants, in order to enable them to enhance resilience against climate risks at their places of origin.

In this light, a translocal resilience perspective could contribute to a more nuanced view of the nexus between environmental change and migration. Through the multiple entry points for policy that translocal resilience opens up, policymakers have options to concretely support migration as a strategy of adaptation.

Migration as Not Failure to Adapt, but Part of Adaptation

Climate change is increasingly threatening human security, especially among vulnerable populations in the global South. Mobility patterns are being influenced and changed. However, the relationship between environmental change and migration is more complex and multilayered than simple representations suggest. Migration in this context should not be seen only as the result of a household’s failure to adapt, but can also be part and parcel of the process of successful adaptation.

Apart from simply better managing migration and instead of deterring it, as many countries have prioritized, there is room to improve migrants’ situations and enhance their ability to contribute to their own and their families’ climate resilience. At places of destination, their legal status, social protections, conditions of work, health, and housing could all be improved, as could their ability to send remittances and stay connected across distances. Origin households could be assisted to better maintain connections and make the most out of the financial and social remittances they receive. Doing so would go beyond managing migration to better managing translocality.

Sources

Ayeb-Karlsson, Sonja, Christopher D. Smith, and Dominic Kniveton. 2018. A Discursive Review of the Textual Use of ‘Trapped’ in Environmental Migration Studies: The Conceptual Birth and Troubled Teenage Years of Trapped Populations. Ambio 47: 557-73. Available online.

Bell, Martin and Elin Charles-Edwards. 2013. Cross-National Comparisons of Internal Migration: An Update on Global Patterns and Trends. Technical Paper No. 2013/01, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), New York. Available online.

Bettini, Giovanni. 2013. Climate Barbarians at the Gate? A Critique of Apocalyptic Narratives on ‘Climate Refugees.’ Geoforum 45: 63–72.

Black, Richard et al. 2011. The Effect of Environmental Change on Human Migration. Global Environmental Change 21 (1): S3-11. Available online.

Borderon, Marion et al. 2019. Migration Influenced by Environmental Change in Africa: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence. Demographic Research 41: 491-544. Available online.

Etzold, Benjamin and Patrick Sakdapolrak. 2012. Globale Arbeit – lokale Verwundbarkeit: Internationale Arbeitsmigration in der geographischen Verwundbarkeitsforschung. In Migration und Entwicklung aus geographischer Perspektive, eds. Malte Steinbrink and Martin Geiger. Osnabrück, Germany: Institut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien (IMIS)-Beiträge.

Gemenne, François. 2011. Why the Numbers Don’t Add Up: A Review of Estimates and Predictions of People Displaced by Environmental Changes. Global Environmental Change 21 (1): S41-49. Available online.

Greiner, Clemens and Patrick Sakdapolrak. 2013. Translocality: Concepts, Applications and Emerging Research Perspectives. Geography Compass 7 (5): 373–84.

Jacobson, Jodi L. 1988. Environmental Refugees: A Yardstick of Habitability. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 8 (3): 257–58.

Kelly, Philip F. 2011. Migration, Agrarian Transition, and Rural Change in Southeast Asia. Critical Asian Studies 43 (4): 479-506. Available online.

Naruchaikusol, Sopon. 2016. Climate Change and Its Impact in Thailand: A Short Overview on Actual and Potential Impacts of the Changing Climate in Southeast Asia. TransRe Fact Sheet No. 2, Department of Geography, University of Bonn, Bonn, June 2016. Available online.

Peth, Simon Alexander and Patrick Sakdapolrak. 2020. When the Origin Becomes the Destination: Lost Remittances and Social Resilience of Return Labour Migrants in Thailand. Area 52 (3): 547-57. Available online.

Peth, Simon Alexander, Harald Sterly, and Patrick Sakdapolrak. 2018. Between the Village and the Global City: The Production and Decay of Translocal Spaces of Thai Migrant Workers in Singapore. Mobilities 13 (4): 455–72. Available online.

Porst, Luise and Patrick Sakdapolrak. 2018. Advancing Adaptation or Producing Precarity? The Role of Rural-Urban Migration and Translocal Embeddedness in Navigating Household Resilience in Thailand. Geoforum 97: 35-45. Available online.

Sakdapolrak, Patrick. 2019. Migration im Kontext des Klimawandels – Indikator für Verwundbarkeit oder Resilienz? Policy brief, German Federal Agency for Civic Education, January 2019. Available online.

Sakdapolrak, Patrick et al. 2016. Migration in a Changing Climate: Towards a Translocal Social Resilience Approach. Die Erde 147 (2): 81-94. Available online.

Sterly, Harald, Kayly Ober, and Patrick Sakdapolrak. 2016. Migration for Human Security? The Contribution of Translocality to Social Resilience. Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs, 3 (1): 57–66. Available online.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Population Division. 2019. International Migrant Stock 2019. Available online.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2009. Human Development Report 2009, Overcoming Barriers: Human Mobility and Development. New York: UNDP. Available online.