Ecuador: Diversity in Migration

For an updated version of this profile, click here.

Haga clic para leer el artículo en español.

Ecuador's geographical variety is nearly matched by its diverse migration patterns. Although it is a small Andean country of approximately 13.3 million people, Ecuadorians are one of the largest immigrant groups in metro New York and the second largest immigrant group in Spain.

In the past 25 years, Ecuador has experienced two major waves of emigration, sending 10 to15 percent of Ecuadorians overseas, mostly to Spain, the United States, Italy, Venezuela, with a small but growing number in Chile.

While the country continues to experience emigration, the number of immigrants, particularly Peruvians and Colombians, has increased in the last five years. Most Peruvians are economic migrants, and the majority of Colombians are refugees, escaping an escalation of armed conflict since 2002 and the hardships created by drug eradication programs (spraying coca crops) in southern Colombia.

The newly elected president, Rafael Correa, has reached out to Ecuadorian communities overseas and has promised to incorporate them into the economic and political life of Ecuador.

Historical Background

The population of what is now Ecuador witnessed considerable disruption between 1470 and 1540. The Inca invaded from Peru during the later half of the 15th century, and Spanish conquerors arrived in 1534. Due to the introduction of disease, abuse, and enslavement, more than 70 percent of the indigenous population died by the end of the century.

Few Spaniards or other Europeans immigrated to Ecuador during the colonial era, which lasted until 1822. The arrival of a few English men, some Spanish traders, and a handful of other Europeans were exceptions.

In the mid-16th century, at least two slave ships from Panama bound for Peru wrecked on the shores of what is now Esmeraldas province. The African slaves established a maroon society (freed slaves), and maintained autonomy during much of the colonial era.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, colonial authorities in Quito arranged for the shipment of African slaves, who were put to work in Ibarra, Guayaquil, and the gold mines of modern-day Colombia (Popayán). A smaller number of slaves were imported to Quito, Cuenca, and other urban areas. The colonial district of Quito, which extended into southern Colombia, had a slave population of approximately 12,000, with an unknown population of slave descendants in Esmeraldas.

With the exception of Spaniards who became traders, Ecuador received very few of the Europeans who emigrated to Latin America during the 19th and early-20th centuries. An 1890 census of Guayaquil, Ecuador's largest city, recorded fewer than 5,000 immigrants, more than half of whom were from Peru.

During Ecuador's cocoa (chocolate) export boom of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, "Lebanese" began to immigrate to Guayaquil and quickly became merchants and traders. The term applies broadly to Arab-speaking, predominantly Christian immigrants whose ancestry can be traced to Syria, Palestine, or Lebanon.

It is unknown how many "Lebanese" migrated to Ecuador, but their economic and political influence has been much greater than their numbers. For example, in 1991 approximately 1,500 Lebanese lived in Quito (out of more than 1.2 million), but two presidents in the 1990s were of Lebanese descent. Also, some of the most successful business families in Ecuador are "Lebanese."

Ecuadorian emigration prior to the 1960s was minimal. A small number of people migrated to Venezuela and by the 1940s to the United States. The U.S. Office of Immigration Statistics (part of the Department of Homeland Security) reports that 11,025 Ecuadorians received lawful permanent resident status from 1930 to 1959. By the 1960s, small communities of Ecuadorians could be found in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York.

Ecuadorian Emigration since the 1960s

The provinces of Azuay and Cañar, and Ecuador's third-largest city, Cuenca, formed the "core" migrant-sending zone in Ecuador in the 1970s and 1980s. In particular, the main sending communities in these areas practiced subsistence agriculture and had a tradition of women weaving Panama hats for export to New York and male seasonal migration to the coast.

When the Panama hat trade declined in the 1950s and 1960s, pioneer migrants, mainly young and male, used this trade connection to migrate to New York, most of them without legal documentation. Most worked in restaurants as busboys or dishwashers, and a smaller number worked in factories or construction.

|

|

||

|

Migration remained slow but persistent during the 1970s; migrants from numerous communities in Azuay and Cañar provinces joined the clandestine migration networks that led people through Central America and Mexico en route to the United States. A small number of Ecuadorians migrated to Venezuela, whose oil-led economy was strong through the 1970s. As oil prices fell in the 1980s, Ecuadorian migration to Venezuela appears to have diminished.

Like many countries in Latin America, Ecuador in the 1970s experienced economic growth and improved living conditions. But in the early 1980s, oil prices collapsed, causing a debt crisis, an increase in inflation, and a dramatic decrease in wages. The crisis, Ecuador's first since 1960, was particularly onerous on subsistence farmers, thousands of whom opted to emigrate as a result.

Most of these migrants paid intermediaries — coyotes or a document forger — for clandestine passage to the United States, overwhelmingly to metro New York, but also to Chicago, Miami, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis. Some migrants were able to borrow the money from relatives, especially a close relative living in the United States; others borrowed from informal economy money lenders.

Ecuadorian men commonly worked in restaurants, and many women worked in sweatshops or as cleaners in office buildings. The Immigration and Reform Control Act of 1986 granted legal permanent resident status to 16,292 Ecuadorians, many of whom have been able to use this legal status to sponsor family members.

Low oil prices and floods that damaged export crops, coupled with political instability and financial mismanagement, caused a second economic crisis in the late 1990s. The national currency, the sucre, lost more than two-thirds of its value, and the unemployment rate rose to 15 percent and the poverty rate to 56 percent.

The crisis was directly responsible for a second wave of emigration, which sent more than half a million Ecuadorians overseas from 1998 to 2004. In contrast to the previous wave, this one was broader. Emigrants came from every province, and they were more urban and somewhat better educated; they also came from various ethnic groups, including members of the Saraguro and Otavalo indigenous groups.

Instead of the United States, the vast majority of these migrants chose Spain, home to only a handful of Ecuadorians at the time. The main reason: an existing agreement allowed Ecuadorians to enter the country as tourists without visas (the law changed in 2003, see sidebar). Indeed, the majority of the first migrants in Spain were women who posed as tourists, often with the help of Ecuadorian travel agencies.

In addition, Spain offered plentiful, low-skilled work in the informal economy, and migrants did not have to worry about language differences. Most women work as domestics while men have found employment in the construction, agriculture, and service industries. By 2002, as many as 200,000 Ecuadorians were residing in Spain.

In addition to Spain, Ecuadorians also went to several other western European countries, most notably Italy, with smaller numbers to France, the Netherlands, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

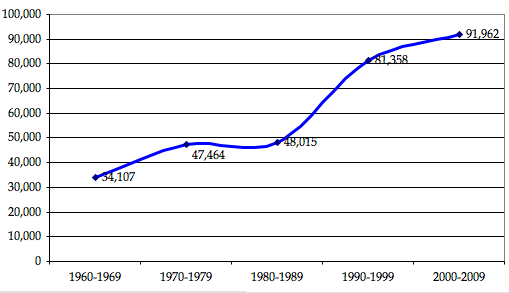

Tightened borders in Central America and greater surveillance at the U.S.-Mexico border made clandestine migration to the United States more expensive and dangerous than migration to Spain. Yet the United States has remained an important destination (see Figure 1). From 2000 to 2005, an average of 9,196 Ecuadorians per year obtained legal residency.

The number who have overstayed visas or entered without authorization is unknown, but thousands have tried. Since 1999, nearly 8,000 Ecuadorians have been detained by the United States Coast Guard in boats destined for intermediary countries such as Guatemala or Mexico. On average, between 1,000 and 2,000 Ecuadorians have been apprehended at the United States border each year in the past decade.

|

|

||

|

Counting Ecuadorians Abroad

Estimates of Ecuadorians living outside the country vary considerably. Adding up the official numbers from top destinations outside Latin America — the United States, Spain, and Italy — provides an estimate of about 986,000 (see Table 1).

In the 2001 Ecuadorian census, 377,908 people were reported to have emigrated in the previous five years (1996 to 2001). But Ecuadorian entrance and exit data suggest that since 1999, nearly a million Ecuadorians (net) left the country. Although Ecuadorian government officials have estimated that as many as 3 million Ecuadorian citizens live overseas, a recent study by the United Nations and an Ecuadorian graduate university (FLACSO) suggest that an estimate of 1.5 million is much more accurate than 3 million.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 2005, Spain reported an Ecuadorian population of 487,239; the vast majority live in Madrid (35 percent), Barcelona (18 percent), and Valencia/Murcia (22.8 percent). Some analysts consider the official figure to be an undercount because not all Ecuadorians in Spain are registered. If that is the case, then the Ecuadorian population in Spain may be between 550,000 and 600,000.

Population estimates for the Ecuadorian population in Italy range as high as 120,000. Italian statistics on the other hand, recorded 61,953 Ecuadorian citizens in 2005, 62 percent of whom were women. Ecuadorians, who are concentrated in Genoa, Milan, and Rome, are the largest Latin American immigrant group in Italy and the 10th-largest national group overall.

Based on the 2005 American Community Survey, the United States Census Bureau estimates there are 436,409 Ecuadorians in the United States — far lower than the "more than one million" commonly reported in Ecuador. Of those Ecuadorians, 62 percent (269,139) reside in the New York-New Jersey metro area, 6 percent in Miami (25,332), and 4 percent in Chicago (18,810). Ecuadorians are the third-largest Latin American immigrant group in the New York-New Jersey metro area, behind Mexicans and Dominicans, and the eighth nationally.

Despite the high estimates common in Ecuador, the U.S. Census Bureau figure is considered low compared with more conservative estimates published in the United States. For example, the Lewis Mumford Institute at the State University of New York, Albany, estimated there were 396,400 Ecuadorians in the United States in 2000. Using this figure, and taking into account continued immigration, it is safe to estimate that the Ecuadorian population is between 550,000 and 600,000.

Remittances and Development Issues

Similar to many Latin American countries, Ecuador depends on the funds its migrants send home. The Inter-American Development Bank estimated that Ecuador received $2.0 billion in remittances in 2004, equivalent to 6.7 percent of its GDP and second only to oil exports; 14 percent of adults in Ecuador receive remittances regularly.

At least 75 percent of remittances are used first for basic household needs — education, food, medicine — and to cancel debts. In 2006, migrants had to pay coyotes or document forgers approximately $12,500 each for clandestine travel to the United States. After basic needs are met and their debts paid off, thousands of Ecuadorians build new homes, replacing modest adobe structures.

In 2002, Ecuador passed a law called the "Program of Help, Savings and Investment for Ecuadorian Migrants and their Families" (Ejecutivo No. 2378-B), and soon thereafter the "Ecuadorian Living Abroad National Plan" was established.

These ambitious laws aim to alleviate migrant debt, create systems of financial intermediation to help with remittances, and establish a system of savings for productive investment and small business creation in the origin communities. Unfortunately, the government implemented little of this agenda until 2006, when the Central Bank of Ecuador reached an agreement with the Spanish bank Caixa for Ecuadorians in Spain to remit money from numerous financial institutions at lower costs.

In 2006, the federal government reported many other development-related achievements. It created a Working Table on Migrants for Employment, which involves multiple governmental and nongovernmental institutions. The group's goals, among others, are to help create public policy on migration and to defend migrant rights. The city of Murcia, Spain, and the province of Cañar, Ecuador, established a codevelopment program funded by the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation. Finally, then-President Alfredo Palacio approved a National Plan of Action to combat kidnapping, illegal migration, and sex trafficking.

Local governments and NGOs have been more active than the national government. For example, Migrant Attention Centers, which provide legal and psychological support for migrant families, have opened in four Ecuadorian cities. The city of Quito was instrumental in the creation of the city's Migrant House, while the Archdiocese of Cuenca (Pastoral Social) funded the center in Cuenca. The centers also oversee a variety of projects designed to help migrant families.

Contemporary Immigration

The 2001 census recorded 104,130 foreign born, or less than 1 percent of Ecuador's population of 12.1 million. Almost half of the foreign born were from Colombia, with 51,556 residents (49.5 percent), followed by the United States (11,112 residents, 10.7 percent) and Peru (5,682 residents, 5.5 percent).

Since the Ecuadorian census recorded everyone who was in Ecuador on November 25, 2001, visitors from the United States were included in addition to the many Americans who work in Ecuador. Only a small part of this figure is attributable to U.S.-born children of Ecuadorians who have returned to Ecuador.

Since 2001, however, thousands more Peruvians and Colombians have arrived. For Peruvians, Ecuador's decision in 2000 to switch its currency to the U.S. dollar from the sucre (dollarization) has been the most important attraction; they also typically earn less than Ecuadorians.

Estimates vary, but it is likely that between 60,000 and 120,000 Peruvians now reside in Ecuador, most without legal permission. Cuenca, situated in the middle of the original "core" migrant-sending zone to the United States, is an especially popular destination for Peruvians because the U.S.-bound migration has tightened the labor market and increased wages. Considering that Ecuador and Peru have been at war several times in the past, most recently in 1995, the arrival of such a large number of Peruvians has been striking.

Colombians are also attracted by dollarization, but more important is the "push" created by an escalation of armed conflict among the Colombian military, paramilitaries, and the rebel group FARC (Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces) since the election of Colombian president Alvaro Uribe and the breakdown of peace talks in 2002.

This violence, coupled with herbicide spraying programs to eradicate coca crops in southern Colombia, have displaced as many as 250,000 Colombians according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The size of the Colombian population in Ecuador is not known, but if UNHCR's estimate is accurate, then a net average of 50,000 Colombians have come to Ecuador each year since 2001.

Determining the actual number of either Colombians or Peruvians in Ecuador is hindered by the fact that the border is porous. Using official migration figures is misleading because entrance and exit data suggest that from 2001 to 2004 nearly 388,000 Colombians should have settled in Ecuador, which is 52 percent higher than even UNHCR's estimate. Similarly, these data suggest that in the same time period a net number of 345,000 Peruvians entered Ecuador, nearly three times the accepted figure.

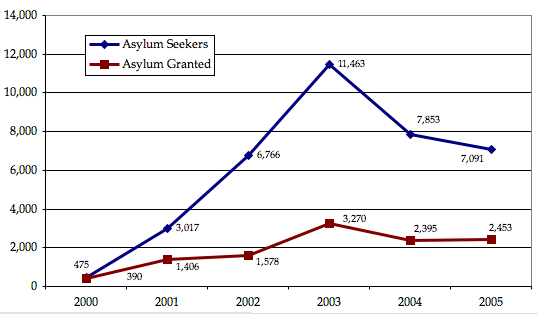

Although not all Colombians who come to Ecuador apply for asylum, they make up the overwhelming majority of people applying for and receiving asylum. According to Ecuador's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, between 2000 and 2005, 36,665 people applied for asylum, with the number of applications peaking in 2003 (see Figure 2). Ninety-seven percent of the applicants were Colombian. Of the total number of applications, 11,492 (31 percent) were granted refugee status, 98 percent of them Colombians.

Advocacy groups have been critical of the Ecuadorian government for denying nearly 70 percent of asylum applications, leaving thousands of families unable or unwilling to return to Colombia.

|

|

||

|

Finally, a moderate number of Chinese and a smaller number of other Asians have immigrated legally to Ecuador very recently, also because of dollarization. The 2001 census recorded 1,214 Chinese, and migration figures since 2001 indicate that on average, a net number of 645 Chinese have arrived annually, although most Ecuadorians suspect the figure is much higher.

Despite their small numbers, the presence of Chinese immigrants is visible in the Chinese discount clothing stores that have appeared in nearly every Ecuadorian city.

Contemporary Migration Issues Facing Ecuador

Ecuador is struggling with its role as an important host country for Peruvians and Colombians. Both groups have been met with suspicion and hostility. Colombians are commonly suspected to be FARC rebels, paramilitaries, drug runners, or other criminals. This suspicion was fueled when, in January 2004, a prominent Colombian rebel was captured in Quito.

Although Peruvians are generally not considered dangerous criminals, they face considerable discrimination, prejudice, and rumored exploitation. Many lead difficult lives and earn little money toiling in the least desirable jobs. Some Ecuadorians accuse Peruvians of stealing Ecuadorian jobs, lowering wages, and engaging in criminal activity, although there is little evidence to support the accusations.

The Ecuadorian government has not addressed the Colombian situation beyond granting asylum to about one-third of applicants, in part because the two countries have a tense relationship. Ecuador objects to Colombia spraying coca plantations so close to the Ecuadorian border and suspects that rebels and paramilitaries use Ecuadorian territory. Thus, many thousands of Colombians continue to live in Ecuador without protected or legal status.

The government has made better progress with Peru, announcing in December 2006 that the two countries are formalizing a bilateral agreement to grant legal status to thousands of Peruvians working in Ecuador. The details of the agreement and how it is carried out will depend on the new president, Rafael Correa, who assumed office in January 2007.

Also of concern to the Ecuadorian government are the dangers migrants face. In 2005, an overcrowded fishing trawler headed for Mexico with more than 100 Ecuadorians aboard sank in rough seas off the Colombian coast, leaving only a few survivors.

Recently, Ecuadorians have become alarmed at reports that young women are being sold into or trapped in sex- slave operations, especially in Europe. To combat the vulnerability of migrants, the Ecuadorian government has begun a campaign to caution would-be migrants to reconsider migrating without legal permission and to know their rights should they go.

In some parts of Azuay and Cañar provinces, entire communities have been transplanted to metro New York. Many of these migrants have built large, brick houses, which are overseen by nonmigrants but are essentially empty until the migrants return. In some communities, thieves have broken into such houses to steal electronic items, money, and other valuables. Communities have responded with neighborhood warning systems and vigilante protection.

The return of migrants from the United States has produced a cultural upheaval, making it difficult for returnees to reintegrate. Many of the migrants from Azuay and Cañar provinces were part of the rural peasantry or urban working poor, with last names that lacked status and were associated with indigenous (Indian) identity. The economic success of these previously marginalized families has caused resentment among some of the families that stayed.

Although most Ecuadorians with legal status in the United States remain there, the children of U.S. residents are known derogatorily as rezis and commonly experience exclusion.

In the areas where much of the emigration has been via clandestine routes, thousands of children have been left behind with the remaining parent, or, in his/her absence, with other family members. A number of the children or adolescents suffer from depression, lack of interest in school, and, reportedly, a high rate of suicide.

Migration Politics and the New President

Migration became a political issue in the 2006 presidential elections, when a 42-year-old economist, Rafael Correa, defeated the wealthiest man in the country, Alvaro Noboa.

Correa named his sister, Pierina Correa, coordinator of migration issues and posted a "Migration Policy" document on his website. In the document, Correa promised to create a "Virtual Consulate" so that migrants could obtain documents more easily, and to elevate the Office of Migration to a cabinet-level ministry. Most dramatically, he proposed changing the constitution to grant Ecuadorians living overseas proportional representation in Congress.

During the campaign, Correa, who had been economics minister in the previous administration, aggressively courted the votes of migrants in the United States and to a lesser extent, in Europe. In 2005, Ecuador passed legislation that allows Ecuadorians living overseas to vote in presidential elections.

In November 2006, 84,110 Ecuadorians living in 42 countries around the world voted in the presidential election. Migrants in Europe supported Correa's opponent, but Correa won the majority of votes in the United States.

Whether or not the Correa administration will be able to follow through on its promises to increase political involvement of migrants remains to be seen, but there is reason for optimism. No other president has paid nearly as much attention to migrants and their families, and it is likely that candidates in the next presidential election (2010) will campaign and raise money among Ecuadorian communities overseas.

Sources

American Community Survey. 2005. United States Census Bureau.

Ayala Mora, Enrique. Resumen de Histoira Del Ecuador. 2005

Bryant, Sherwin 2006. "Finding Gold, Forming Slavery: The Creation of a Classic Slave Society, Popayán, 1600-1700." The Americas 63(1):81-112 July, 2006.

"Ecuador: Las cifras de la migración nacional." UNFPA and FLACSO, Quito, Ecuador, December, 2006.

Herrera, Gioconda, Maria Cristina Carillo, and Alicia Torres. "La migración ecuatoriana: transnacionalismo, redes, e identidades." FLACSO-Plan Migración, Comunicación y Desarrollo, Quito, Eucador.

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo. Ecuador 2001 Census.

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo. 2006. Ecuador Migration Statistics.

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Spain. 2006. Municipality Survey.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Italy. 2006. "Demography in Figures: Residency Foreigners."

Inter-American Development Bank. 2006. "Remittances 2005: Promoting Financial Democracy,"

Jokisch, Brad, Pribilsky, Jason. "Economic Crisis and the New Emigration from Ecuador" International Migration, 40(4):75-102, 2002.

Kyle, David. 2001. Transnational Peasants.

Lane, Kris. 2002. Quito 1599: City and Colony in Transition. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Newson, Linda A. 1995. Life and Death in Early Colonial Ecuador.

Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Ecuador. 2006. Personal Communication.

Roberts, Lois J. 2000. The Lebanese Immigrants in Ecuador.

Sistema Integrado de Indicadores Sociales de Venezuela. 2000 Census.

United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees. 2006.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2006. "2005 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics."