You are here

Greece Struggles to Balance Competing Migration Demands

A woman looks out over tents being used by migrants and asylum seekers on the Greek island of Lesvos. (Photo: Amanda Nero/IOM)

In July 2019, Kyriakos Mitsotakis was elected prime minister of Greece, and soon announced what he termed “strict but fair” reforms to Greece’s migration policies. These proposals raised expectations that asylum seekers would enter a more efficient system without the overcrowded refugee camps of the past. Yet conditions on frontline islands did not change in meaningful ways. The following September, a major fire broke out in the Moria camp on the island of Lesvos, destroying most structures and displacing more than 10,000 of the 13,000 asylum seekers housed there. The fire marked a desperate coda to the Mitsotakis government’s attempted reforms and reflected the enduring nature of the tensions that have long complicated Greece’s migration policy.

Over its first year, Greece’s new government sought to calibrate a response addressing migration fatigue among Aegean island host communities taxed by the arrival of tens of thousands of asylum seekers over the past several years, pressure from the European Union to prevent onward movement, and tensions with Turkey. At first, Mitsotakis had little to show for his reform efforts. Irregular arrivals increased over the second half of 2019, and reception centers for asylum seekers in island hotspots had filled to bursting. Asylum proceedings remained painfully slow, EU burden-sharing was conspicuous in its absence, and repatriations of rejected asylum seekers had stalled.

These results prompted protests in the North Aegean in early 2020. As the government tried to reckon with these tensions, Turkish authorities unilaterally opened their western borders to asylum seekers, triggering sudden, large-scale movements toward Greece. While Turkey’s brinksmanship played out, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the region. The outbreak temporarily halted irregular migration and muffled tensions in the Aegean, but left unresolved the underlying destabilizing factors. Since then, emboldened Greek authorities have used increasingly questionable methods to reduce new arrivals and confine asylum seekers already in the country.

This article traces Greece’s migration policy over the Mitsotakis government’s first year in office. It begins by focusing on the reforms announced in 2019, then details the parallel domestic and foreign policy crises that erupted in spring 2020. It assesses how, as internal and geopolitical tensions were boiling over, the pandemic struck and delayed the impending reckoning. It concludes by reflecting on the new government’s actions and their implications for the future of migration in the Aegean.

The Government’s Early Migration Reform Efforts

The electoral campaign by Mitsotakis and his center-right New Democracy party promised more effective migration management and stricter border controls. Just three days after taking power, the government revoked a decree allowing asylum seekers to obtain social security numbers, arguing it was counterproductive to issue permanent numbers to people whose asylum claims might be rejected. Instead, the new administration promised to create a parallel, provisional social security registry for asylum seekers, although this registry took seven months to roll out and left thousands without access to health care in the interim.

This move set the tone for subsequent reforms. While the government’s changes reduced rights and benefits for asylum seekers and refugees, they did not address the structural problems hobbling Greece’s reception and asylum determination systems, nor make its overall migration management more effective. Neither did they lead to greater transfers to other EU Member States or facilitate greater cooperation with Turkey.

Legal Reforms: The 2019 Law on International Protection

In November 2019, the Hellenic Parliament approved the International Protection Act (IPA). To speed up asylum decisions and clear backlogs, the law expanded use of an accelerated border procedure adjudicating asylum claims and appeals within 20 days, leaving very little time for asylum seekers to seek scarce legal assistance. It also made it more difficult for asylum seekers to obtain a vulnerability determination allowing them to bypass the accelerated border procedure, for example removing diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from the list of qualifying conditions.

The IPA introduced new procedural formalities to asylum proceedings and made it easier to reject claimants who fell afoul of them. In one extreme example, over several days in November 2019, 28 sub-Saharan Africans saw their asylum claims rejected after they failed to respond to the questions of asylum officers at their hearings. The reason for this was that there were no interpreters available to help them communicate.

Although Mitsotakis had promised to accelerate asylum proceedings, his government did not expand staffing of the Greek Asylum Service until February, announcing 220 hires to reinforce its existing staff of 886. Around the same time, the government signed an agreement with the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) to double personnel in Greece to more than 1,000. Meanwhile, the number of pending asylum applications had grown from just over 72,000 at the end of September 2019 to more than 97,000 at the end of February 2020.

The new government also intended to accelerate repatriations from Greece. However, while repatriations averaged nearly 16,000 per year in the preceding government’s four full years in power, just 9,700 repatriations took place in 2019 (quarterly figures are not available, making it difficult to determine how many of these took place under which government). Mitsotakis had also promised to energize returns to Turkey of asylum seekers found inadmissible under the EU-Turkey deal, but it carried out only 255 from July 2019 to March 2020. In the first half of 2020, 1,343 repatriations took place in total, although the COVID-19 pandemic halted many such movements globally.

Decongesting the Islands: Transfers to the Mainland and an Appeal for European Solidarity

Soon after taking power, the Mitsotakis government began trying to move asylum seekers and refugees from overcrowded Aegean Reception and Identification Centers (RICs) to mainland Greece. From July 2019 to March 2020, when the population of the Aegean camps peaked, nearly 30,000 people left the islands, though not always without incident. Occasionally, buses carrying asylum seekers to mainland facilities were turned back at informal roadblocks, and some hotels designated to serve as reception centers received threats. New arrivals, moreover, outpaced transfers; over the same period, nearly 55,000 migrants arrived by sea. Greece’s island RICs, which have a stated capacity of just over 6,000, grew from hosting 17,000 asylum seekers to nearly 40,000.

Mitsotakis asked fellow EU Member States for solidarity, but his appeals fell on deaf ears. Just one out of 27 replied to an October 2019 letter requesting help relocating 4,000 unaccompanied minors then living in Greece. Not until March 2020 would the European Commission announce a plan to relocate unaccompanied minors from Greece, eventually committing to receive 2,000. Only about 200 transfers had taken place before the Moria fire, though multiple countries have announced plans to accept additional minors in its aftermath.

In mid-November, the Greek government announced it would close RICs on frontline islands and replace them with closed facilities in which asylum seekers would be held throughout their asylum process. Regional and local authorities quickly denounced the plan, fearing that the new centers would become permanent, and demanded instead the prompt decongestion of the islands. The government backed down, taking no further action in 2019.

Integration Outcomes Stall or Reverse

The government also scaled back the Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation (ESTIA) program, which provides cash allowances to asylum seekers and refugees in Greece and hosts about 20,000 in rented apartments. The IPA codified a preexisting but loosely enforced six-month cap on continued ESTIA benefits for recognized refugees; an amendment later shortened it to one month starting in March 2020. The government argued the changes would promote autonomy, prevent dependency, and increase capacity to transfer asylum seekers to the mainland. However, it reduced this benefit without offering counterbalancing measures. The HELIOS transitional support program, launched the previous June, had enrolled fewer than 8,000 refugees at the time ESTIA benefits were reduced to one month, and only a fraction of enrollees had received rental subsidies. Dozens of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) claimed that ESTIA reductions could push thousands of vulnerable families into destitution and homelessness.

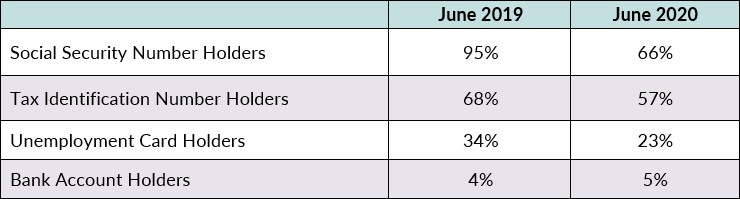

The Mitsotakis government made little progress helping recognized refugees access livelihoods. Workforce participation by refugees in Greece is negligible, partly because of language barriers and partly because of difficulties obtaining certain identity documents. From June 2019 to June 2020, every economic inclusion indicator measured by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) showed outcomes had either worsened or barely improved for asylum seekers and refugees accommodated under ESTIA (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Greece Meeting Various Economic Inclusion Indicators, 2019-20

Note: Figures refer to asylum seekers and refugees living in accommodation provided under Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation (ESTIA).

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Fact Sheet: Greece, 1-30 June 2019,” UNHCR, Athens, July 2019, available online; UNHCR, “Fact Sheet: Greece, 1-30 June 2020,” UNHCR, Athens, July 2020, available online.

Progress on access to formal education also stalled. Although the number of displaced children in Greece had grown from nearly 29,000 to more than 45,000 between April 2019 and April 2020, the number enrolled in formal education only grew from 11,500 to 13,000. As of early 2020, just 61 percent of refugee children living on the mainland and 6 percent of those living on the islands were enrolled in formal education. Informal education on the islands, mostly run by NGOs, reached only 28 percent of children there.

Spring 2020: Crises Mount

On January 22, nearly 10,000 residents demonstrated in Lesvos under the slogan “we want our islands back,” demanding solutions to problems that had festered for half a decade: near-constant irregular arrivals, growing numbers of asylum seekers in squalid camps, and the strain on infrastructure and services. Mitsotakis had pledged to resolve these problems, but they had worsened under his watch. Two weeks later, hundreds of asylum seekers living in Moria staged their own demonstration, marching peacefully to Mytilene to demand better living conditions and faster asylum proceedings; they were stopped by riot police with tear gas and flash grenades.

As tensions rose, the government responded by pledging to build the closed structures it had proposed the previous November. This proved a grave misjudgment of how islanders would react. Local authorities blocked ferry ports and obstructed access to construction sites. When military construction crews escorted by riot police arrived on February 25, they met fierce, quasi-insurrectionary resistance in Lesvos and nearby Chios. Subsequent clashes between police and local protesters left dozens injured over two days. Rebuked by both regional authorities and local communities, the Mitsotakis government reversed itself, and construction crews and riot police withdrew after 48 hours.

Domestic Unrest Superseded by Geopolitics

Before a meaningful dialogue could be established, however, geopolitics intervened to redirect the tensions. On February 27, Turkish authorities unexpectedly announced they were opening their western borders to asylum seekers heading to Europe. Thousands soon gathered at the Kastanies border crossing and at Turkey’s shores. On March 1 alone, 736 asylum seekers reached Greece by boat, a four-fold increase compared to February 1, although the number of maritime arrivals would drop again over the following days.

The move redirected the target of frustration in the Aegean from Athens to Ankara. Greece’s public discourse took on military overtones as officials accused Turkey of orchestrating an “asymmetric” invasion. Police and military forces, with assistance from the EU border agency Frontex, prevented large-scale arrivals and secured Greece’s land borders with tear gas, water cannons, and, according to multiple reports, deadly force. News outlets and NGOs reported that dozens of asylum seekers suffered serious injuries, and that at least two were killed. (Greek authorities have flatly denied using deadly force or other breaches of the law, despite evidence from digital forensic analysis and multiple videos taken at different scenes.) At sea, a 4-year-old boy drowned after the dinghy he and 47 other passengers were in capsized off the Lesvos coast.

While Greece’s October appeals for relocating unaccompanied minors had gone unmet, European support was immediate in March. At the Greco-Turkish border, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen praised Greece as Europe’s “aspida” (“shield”). Greece suspended all new asylum registrations for the month of March, for which it was criticized by UNHCR and others—but notably not the Commission. The government eventually relented, allowing most people who arrived in March to lodge asylum applications.

Turkey’s gambit transformed the February confrontations on the islands. What had begun as a clash between the central government and regional authorities over managing arrivals and reception took on a nationalist framing. Soon, however the COVID-19 pandemic reached Greece and Turkey, transforming the situation yet again.

COVID-19 Arrives

Greece confirmed its first COVID-19 case on February 26, and in subsequent weeks the government imposed a national lockdown, closed nonessential services, and imposed travel restrictions. Many of these swift actions won praise for Mitsotakis. Greece’s new infections curve remained flat through the spring and early summer. Although transmission grew in August as tourism reopened, as of early September Greece had recorded fewer than 12,000 cases.

The global lockdown also undercut the rising tensions at the border. After the disturbances of late February and early March, irregular arrivals plummeted to just a few dozen per month.

At the same time, the pandemic provided the government with a new rationale to confine asylum seekers on the islands. On March 17, the government ordered a strict lockdown of every island reception center. It also closed the asylum service for ten weeks. Even as lockdowns eased across Greece and tourists began returning, RIC lockdowns were extended continually and remained in place as of late September.

Emerging from the Spring Crisis

By early summer, the spring confrontations between the government and islanders had been supplanted by Turkey’s gambit and COVID-19. Yet while the underlying issues remained unresolved, the government turned towards expedient stop-gap measures. Although it had not been able to build closed reception centers, the facility lockdowns served the same purpose, confining most inhabitants inside. And after receiving EU praise for its forceful defense of Europe’s external borders, the government continued testing the limits.

Over the summer, repeated allegations surfaced of unlawful pushbacks at Greece’s maritime borders and from the interior, including the use of extrajudicial detention. An unknown number of migrants have been towed back to Turkish waters or forcibly dropped at sea by Greek and Frontex officials, some episodes of which have been documented by the media, NGOs, and public officials. In one case, Danish media reported in March that a Danish patrol boat operating in the Aegean had been ordered by Frontex commanders to force 33 people back onto their dinghy and tow them into Turkish waters. The crew refused to follow the order, bringing them instead on the island of Kos. In August, Germany’s deputy defense minister confirmed two further incidents, including the return to Turkish waters in late April of migrants who had reached Chios. In late August, UNHCR raised alarm over the growing number of credible reports and asked Greek authorities to investigate them and refrain from such practices. When confronted, however, Greek officials have held fast to a flat denial: Greek security forces respect all relevant international law, and allegations to the contrary are “fake news.”

Conditions steadily worsened in the reception centers throughout the summer, with inhabitants growing anxious due to the extended lockdowns and uncertainty resulting from the closure of the asylum service. Three asylum seekers died in Moria during lockdown, two in violent altercations and another in an apparent drug overdose. Two major fires broke out in April at RICs on the islands of Chios and Samos, following disturbances at each site.

In September, COVID-19 outbreaks were identified in the reception centers in Chios, Samos, and Lesvos. On September 9, multiple fires broke out in Moria, destroying most of its structures and leaving more than 10,000 people homeless. Greek authorities arrested five former inhabitants whom they accused of starting the fires in protest after the coronavirus had been detected in the camp.

The Importance of Values in Migration Policymaking

Since 2015, Greece has borne a disproportionate share of the burden of the EU migration crisis. It has had to do so from a weak position, stuck between EU institutions and Member States that have treated Greece as a buffer for the rest of the European Union, and Turkish authorities who view Greece’s borders as a prime means of maximizing leverage with the bloc.

The only way out of this difficult position is for Greece to develop a clear and coherent approach to migration management that carefully balances the opportunities and limitations of its domestic and foreign policy priorities. This balancing act is complex and difficult to articulate in political terms, especially to an impatient electorate. This makes it all the more important for Greek authorities to be flexible and transparent in their conduct.

Domestically, the Mitsotakis government has needed to address asylum seekers’ demands for prompt and dignified processing, refugees’ needs for gainful integration, and host communities’ need for stability, especially on the islands. Instead, it has eroded the rights of the former two while disregarding the demands of the latter.

Internationally, the government has had to confront the fact that its migration outcomes are conditioned by choices made elsewhere in Europe and in Turkey. However, in the face of European refusals to accept transfers and increasing confrontation with Turkey, the Greek administration has resorted to questionable border-control measures, which it has papered over with unconvincing denials.

Failing to account for these competing demands has affected Greece’s migration management system at every level. Arrivals continue accumulating in overcrowded reception centers, where the infrastructure is insufficient to host them in minimally acceptable conditions or quickly process their claims. Asylees face high barriers to access public services, education, and livelihoods. Solidarity from EU institutions and Member States remains tilted toward border control, not relocation.

Meanwhile, the European Union’s uncritical defense of hardline border controls erodes its professed commitment to human rights and international law. The bloc’s stance also weakens its negotiating position vis-à-vis Turkey, undermining its ability to accuse Ankara of acting in bad faith and violating international commitments.

The shortcomings of the Mitsotakis government’s migration reforms were dramatically illustrated by the September fires that destroyed the Moria facility. If this conflagration leads to profound reflection and serious reforms, yielding truly “strict but fair” migration management, Greece may yet be able to change course. Continuing to rely on expedients, however, can only further feed tensions that have undergirded the confrontations with islanders and the fires in Moria.

Sources

Amnesty International. 2019. Greece Must Immediately Ensure that Asylum-Seekers, Unaccompanied Children and Children of Irregular Migrants Have Free Access to the Public Health System. Press release, October 14, 2019. Available online.

Bathke, Benjamin. 2019. Greek Villagers Throw Stones at Migrant Buses. InfoMigrants, October 25, 2019. Available online.

---. 2020. 18 Unaccompanied Minors from Greek Camps Relocated to Belgium. InfoMigrants, August 5, 2020. Available online.

Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMD). 2020. BVMN Visual Investigation: Analysis of Video Footage Showing Involvement of Hellenic Coast Guard in Maritime Pushback. Border Violence Monitoring Network, August 21, 2020. Available online.

Bourdaras, Giorgos. 2019. Greek PM Unveils Four-Point Plan for Migration. Ekathimerini, October 5, 2019. Available online.

Council of Europe. 2020. Commissioner Seeks Information from the Greek Government on Its Plans to Set-Up Closed Reception Centres on the Aegean Islands. Press release, December 3, 2019. Available online.

Deeb, Bashar. 2020. Samos and the Anatomy of a Maritime Push-Back. Bellingcat, May 20, 2020. Available online.

Deeb, Bashar and Leone Hadavi. 2020. Masked Men on a Hellenic Coast Guard Boat Involved in Pushback Incident. Bellingcat, June 23, 2020. Available online.

Ekathimerini. 2019. Five East Aegean Islands Reject Plan for Closed Migrant Centers. Ekathimerini, November 29, 2019. Available online.

---. 2020. Greece to Grant Provisional Social Security Number to Asylum Seekers. Ekathimerini, February 3, 2020. Available online.

European Asylum Support Office (EASO). 2020. EASO Operations in Greece to Expand Significantly. Press release, January 29, 2020. Available online.

European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). 2020. Greece: Situation in Lesvos Intensifies after Police Crackdown on Protesters. Press release, February 7, 2020. Available online.

Eurostat. 2020. Third Country Nationals Returned Following an Order to Leave - Annual Data (Rounded). Last updated June 5, 2020. Available online.

Evans, Dominic and Orhan Coskun. 2020. Turkey Says It Will Let Refugees into Europe after Its Troops Killed in Syria. Reuters, February 27, 2020. Available online.

Fallon, Katy. 2020. How Greece Managed to Flatten the Curve. The Independent, April 8, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. ‘We Want Our Islands Back’ – Greeks Protest Against Asylum Seeker Burden. The Irish Times, February 3, 2020. Available online.

Fallon, Katy and Alexia Kalaitzi. 2020. ‘Boats Arrive, People Disappear’: One Greek's Search for Missing Refugees. The Guardian, June 19, 2020. Available online.

Fox, Alanna and Devon Cone. 2020. Without Essential Protections: A Roadmap to Safeguard the Rights of Asylum Seekers in Greece. Washington, DC: Refugees International. Available online.

Guardian, The. 2019. Greece to Replace Island Refugee Camps with 'Detention Centres.' The Guardian, November 20, 2019. Available online.

Greece General Secretariat for Crisis Management Communication. 2019. National Situational Picture Regarding the Islands at Eastern Aegean Sea. Accessed September 22, 2020. Available online.

Greece Ministry of Migration and Asylum. 2019. Statistical Data of the Greek Asylum Service. Updated October 3, 2019. Available online.

---. 2020. Statistical Data of the Greek Asylum Service. Updated March 9, 2020. Available online.

Jalbout, Maysa. 2020. Finding Solutions to Greece’s Refugee Education Crisis. London: Theirworld. Available online.

Karamanidou, Lena and Bernd Kasparek. Hidden Infrastructures of the European Border Regime: the Poros Detention Facility in Evros, Greece. Respond blog post, March 8, 2020. Available online.

Kitsantonis, Niki. 2020. Riot Police Pulled from Greek Islands After Clashes Over New Camps. The New York Times, February 27, 2020. Available online.

Konstantinou, Alexandros, Aikaterini Drakopoulou, Eleni Kagiou, Panagiota Kanellopoulou, Aliki Karavia, et al. 2020. Country Report: Greece, 2019 Update. Brussels: European Council on Refugees and Exiles. Available online.

Kouparanis, Panagiotis. 2020. Το Βερολίνο καταλογίζει στην Αθήνα παράνομες επαναπροωθήσεις. Deutsche Welle, August 11, 2020. Available online.

Louarn, Anne-Diandra. 2019. Procédures d’Asile Accélérées, Expulsions vers la Turquie : Que Signifie l’Election de Mitsotakis pour les Migrants en Grèce ? InfoMigrants, July 8, 2019. Available online.

Michalopoulos, Sarantis. 2019. EU Governments Ignore Greek Request to Help 4,000 Child Refugees. Euractiv, November 6, 2019. Available online.

Papastergiou, Vassilis and Eleni Takou. 2019. Persistent Myths about Migration in Greece. Athens: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. Available online.

Rankin, Jennifer. 2020. Migration: EU Praises Greece as 'Shield' after Turkey Opens Border. The Guardian, March 3, 2020. Available online.

Refugee Support Aegean. 2020. Lack of Effective Integration Policy Exposes Refugees in Greece to Homelessness and Destitution, While Returns from European Countries Continue. Refugee Support Aegean, June 4, 2020. Available online.

Smith, Helena. 2020. Child Dies Off Lesbos in First Fatality Since Turkey Opened Border. The Guardian, March 2, 2020. Available online.

Tritschler, Laurie. 2020. Danish Boat in Aegean Refused Order to Push Back Rescued Migrants. Politico, March 6, 2020. Available online.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2019. Refugee and Migrant Children in Greece as of 30 April 2019. Fact sheet, UNICEF, Athens, April 2019. Available online.

---. 2020. Refugee and Migrant Children in Greece as of 30 April 2020. Fact sheet, UNICEF, Athens, April 2020. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019. Fact sheet: Greece 1-30 June 2019. Fact sheet, UNHCR, Athens, July 2019. Available online.

---. 2020. Fact sheet: Greece 1-30 June 2020. Fact sheet. UNHCR, Athens, July 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Returns from Greece to Turkey (Under EU-Turkey Statement) as of 31 March 2020. Fact sheet, UNHCR, Athens, April 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. UNHCR Concerned by Pushback Reports, Calls for Protection of Refugees and Asylum-Seekers. Press release, August 21, 2020. Available online.

Varvia, Christina, Stefanos Levidis, Dimitra Andritsou, Kishan San, Nour Abuzaid, et al. 2020. The Killing of Muahammad Gulzar. Forensic Architecture, May 8, 2020. Available online.

Varvia, Christina, Stefanos Levidis, Kishan San, Dimitra Andritsou, Nour Abuzaid, et al. 2020. The Killing of Muahammad al-Arab. Forensic Architecture, March 7, 2020. Available online.

Weizman, Eyal, Christina Varvia, Stefanos Levidis, Nathan Su, Bethany Edgoose, et al. 2020. Shipwreck at the Threshold of Europe. Forensic Architecture, February 19, 2020. Available online.