You are here

Brain Drain and Brain Gain in Hong Kong’s Population Shuffle

People walk through the streets of Hong Kong. (Photo: iStock.com/danielvfung)

In the wake of political unrest, efforts to increase security ties to China, and the global COVID-19 pandemic, Hong Kong has experienced a pronounced exodus, contributing to a drop in its domestic population of young professionals and others. Chief Executive John Lee has reported his city of approximately 7.5 million people saw its labor force shrink by around 140,000 individuals from 2020 to 2022, an outflow that reduced both labor supply and domestic consumer demand. As emigrants relocate, they take their wealth with them; Bank of America projected in 2021 that capital flight from Hong Kong could reach nearly $76 billion by 2025. Moreover, the departure of skilled workers, aided by new immigration policies in the United Kingdom and Canada to welcome Hong Kongers, undermines Hong Kong’s position as a global financial and business hub, raising alarms about intensifying brain drain.

In This Article

-

Hong Kongers’ emigration patterns are rooted in the region’s unique history

-

A combination of political unrest and pandemic restrictions have contributed to recent emigration

-

Top destinations are the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia

-

Mainland Chinese are immigrating through talent-focused pathways

With the world’s lowest fertility rate, at 0.8 births per woman, according to the World Bank, Hong Kong also faces a demographic predicament. Nearly 30 percent of the special administrative region’s population will be aged 65 and above by 2040.

To ensure its aging and emigrating workforce can be replaced, Hong Kong has enacted comprehensive initiatives aimed at drawing high-potential immigrants, including the Top Talent Pass Scheme (TTPS). Launched in December 2022, TTPS received more than 100,000 applications within its first six months, two-thirds of which were approved. Approximately 95 percent of approved applicants have been from mainland China.

TTPS and other talent immigration schemes are clearly working. After several years of decline, Hong Kong’s population increased by 2.1 percent from June 2022 to June 2023, due in large part to net immigration of 174,000 people. With many Hong Kongers leaving and mainlanders arriving, the city is poised for a demographic shift. This population swap may make Hong Kong more culturally and politically similar to the mainland, although the long-term trajectory remains unclear. In March, Hong Kong lawmakers approved a national security law widely interpreted as bringing the city closer politically and economically to Beijing. This article details Hong Kong's changing migration trends at a crucial inflection point in its history.

Hong Kong’s Colonial History and Unique Position

Hong Kongers’ emigration patterns are rooted in the region’s unique history. Located on the southeastern border of China, Hong Kong—a peninsula and cluster of small islands—was a British colony until 1997, when it was transferred to mainland China. British rule transformed Hong Kong from a fishing village into a global trade port and international commerce hub. In the modern era, Hong Kong established a position as Asia’s financial center, connecting global businesses and investors to the Chinese market.

At the handover in 1997, leaders from China and the United Kingdom signed a formal pact promising the creation of a “one country, two systems” framework that would sustain Hong Kong’s capitalist economy, independent judiciary, and high-level of autonomy for the next 50 years. These benchmarks are declared in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini constitution.

As a special administrative region of China, Hong Kong maintains a separate border control system from the mainland, necessitating travel documents for crossing. Despite Hong Kong being a part of China, mainlanders need special entry permits. Additionally, Hong Kong issues its own passports, which grant holders visa-free access to 171 countries, unlike mainlanders’ passports which face more restrictions. These arrangements underscore a unique aspect of Hong Kong’s integration with the mainland, reflecting its distinct territorial and administrative identity under the one country, two systems framework.

Why Emigration? Political Unrest and Pandemic Restrictions

Less than 25 years after returning to Chinese control, Hong Kong’s autonomy was challenged by a proposed extradition bill in 2019 that would have allowed Hong Kongers accused of crimes to undergo trial on the mainland. The legislation elicited widespread fears about the possibility of political persecution. The situation in Hong Kong grew increasingly tumultuous, resulting in likely the largest demonstrations in the city’s history, and tensions escalated further with the implementation of the National Security Law (NSL) in 2020, which targets “secession, subversion, terrorist activities, and collusion with a foreign country or external elements to endanger national security.” The introduction of the NSL intensified public concerns about political stability and personal freedoms in Hong Kong, triggering large-scale emigration.

During the pandemic, Hong Kong followed Beijing’s “zero-COVID” strategy, which emphasized achieving zero infections. Rigid lockdowns and mobility restrictions in 2021 frustrated foreigners living in Hong Kong, driving them away. With both migrants and natives leaving, the city experienced three consecutive years of population decline.

Push Factors for Emigration

In 2020, 44 percent of respondents in a Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) survey indicated that they would move overseas if given the chance, and 35 percent said they had taken actions to prepare for a move. Political and social dissatisfaction were the predominant reasons given for considering emigration. The most cited factors were dissatisfaction with the government (27 percent), political and social divisions (24 percent), reduced rights and freedoms (20 percent), and lack of democratic governance (18 percent). In comparison, the pull factors for overseas residency were primarily associated with a higher standard of living, more individual liberties and democratic practices, and children’s education and professional prospects.

Moreover, Hong Kong parents are motivated to emigrate due to the city’s perceived diminishing educational quality since NSL’s passage, a decline that had been attributed to the incorporation of national security education into school curricula. Researchers also have noted a gradual erosion of Hong Kongers’ trust in the legal system, coupled with a heightened awareness of global citizenship.

Hong Kongers in the United Kingdom—the most popular destination, as detailed below—were overwhelmingly driven by political reasons, according to a 2023 University of Liverpool study. Among these, judicial independence and various freedoms emerged as the most critical concerns, although other factors included the cost of living, the presence or absence of civil society, and overall quality of life. Hong Kong emigrants are therefore not only leaving political turbulence and societal divisions, but also seeking a higher quality of living including freedom and prosperity.

Younger people in particular are the most likely to emigrate from Hong Kong, according to a 2024 Hong Kong University (HKU) Business School study analyzing LinkedIn data of people migrating to and from Hong Kong. Meanwhile, the city is attracting a significant number of well-educated and older professionals. New arrivals tend to be ethnically Asian and possess fewer LinkedIn connections compared to those who are leaving.

These migration patterns indicate Hong Kong’s workforce is becoming less international and more embedded in East Asia. While emigration of younger workers could pose a challenge for the city over time, the influx of older, seasoned professionals could offset those headwinds. The trend may suggest a shift in Hong Kong’s business environment away from being a truly global hub and towards specifically Asian or mainland Chinese markets, potentially altering its traditional business approach and cosmopolitan character.

Where Have the Emigrants Gone?

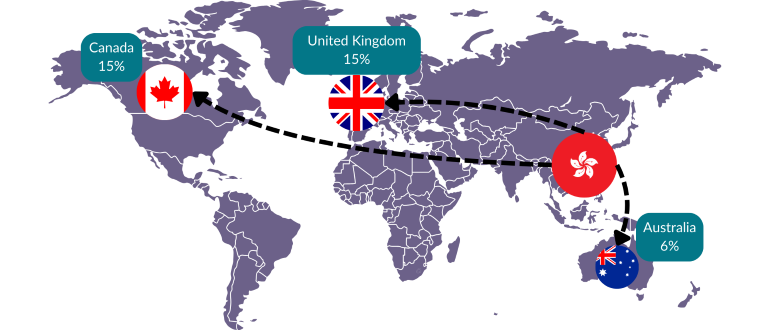

The top destinations for Hong Kongers contemplating emigration are the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Taiwan, according to a 2022 version of the CUHK survey (see Figure 1). Notably, both the United Kingdom and Canada have opened special immigration pathways for Hong Kong residents since the region’s anti-extradition and pro-democracy protests.

Figure 1. Top Destinations for Hong Kong Emigrants and Would-Be Emigrants, 2022

Note: Figure shows preferred destinations of emigrants as well as Hong Kongers planning to emigrate.

Source: Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), Communications and Public Relations Office, “Survey Findings on Views about Emigration from Hong Kong Released by the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies at CUHK” (press release, October 27, 2022), available online.

The United Kingdom Anticipates Influx of Migrants and Capital

The United Kingdom introduced a dedicated immigration pathway for British National (Overseas) (BN[O]) status holders and their dependents in January 2021, in response to the imposition of the NSL. The UK government deemed China’s actions around the time to be a violation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration that set the terms for Hong Kong’s handover, and claimed that Beijing infringed upon the liberties of Hong Kong citizens. The Home Office termed the dedicated migration pathway a manifestation of London’s “historic and moral commitment to those people of Hong Kong who chose to retain their ties” to the United Kingdom.

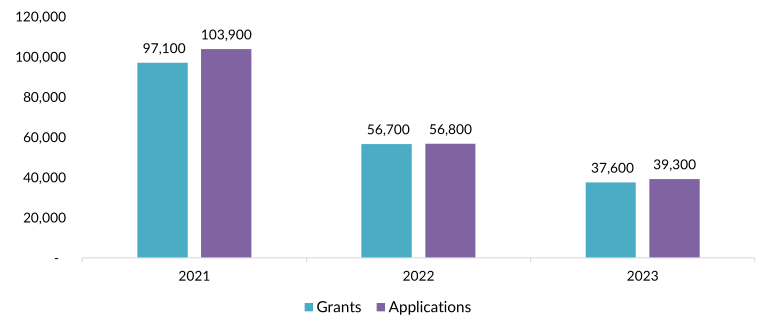

BN(O) status has been available to Hong Kong residents born before the 1997 handover to China, as well as their families, but previously allowed only a temporary visa-free UK stay of up to six months. The UK government estimated that approximately 2.9 million individuals were eligible to relocate permanently under this scheme, plus an additional 2.3 million dependents. Through 2023, more than 191,000 BN(O) visas were granted, and 140,000 people have arrived through this pathway (see Figure 2). With 96 percent of applications approved, this program is on track to meet initial projections that between 258,000 and 322,400 BN(O) holders would immigrate within five years. The government has estimated that these new arrivals would contribute over 2 billion pounds in net economic benefits.

Figure 2. UK Grants and Applications of British National (Overseas) Visas to Hong Kong Nationals by Year, 2021-23

Source: UK Home Office, “Safe and Legal (Humanitarian) Routes to the UK,” February 29, 2024, available online.

Still, integration into a new society proves challenging for many. Just 30 percent of Hong Kong immigrants in the United Kingdom had secured full-time employment by late 2022, according to a University of Liverpool estimate, despite their exceptionally high educational attainment. Approximately 59 percent of Hong Kongers in the United Kingdom have undergraduate degrees, and 23 percent have postgraduate qualifications, according to the Welcoming Committee for Hong Kongers and British Future. However, 20 percent of Hong Kong immigrants were in temporary jobs as of November 2023, which is more than three times the UK national average of 6 percent. Additionally, nearly half of Hong Kong immigrants who are employed felt their roles were not commensurate with their skills and experience: 27 percent reported there was no match and 20 percent said there was only a slight match. These figures underscore underemployment and skill underutilization among the BN(O) visa holders. Virtually all immigrants from Hong Kong say they plan to seek permanent settlement and British citizenship, so successful integration will require more efforts from policymakers, community organizations, and migrants themselves.

Canada Embraces Indo-Pacific Engagement

Canada has introduced two programs to streamline Hong Kongers’ permanent immigration. Under these initiatives, in effect from 2021 to mid-2026, Hong Kongers who have recently graduated from Canadian higher education institution or have a year of Canadian work experience can apply for residency with their immediate families. Individuals must already be in Canada on a temporary visa, although the government in 2021 also launched a new work permit for eligible Hong Kongers. These policies aim to incentivize Hong Kong youth to pursue higher education in Canada and are part of the country’s strategic effort to appeal to skilled immigrants more generally. Canada’s immigration schemes are part of its Indo-Pacific Strategy, which aims to enhance its presence in regional security and economic growth.

In 2022, Canada approved more than 7,900 study permits for students from Hong Kong, a 25 percent increase from the previous year. As of April 2023, nearly 2,400 Hong Kongers had become Canadian permanent residents through education, while more than 760 acquired residency through work experience, according to Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

Arrivals in Hong Kong: Mainland Chinese Dominate Talent Migration

Hong Kong is targeting the immigration of various groups through seven distinct talent admission schemes, including TTPS, the Quality Migrant Admission Scheme (QMAS), and the Technology Talent Admission Scheme (TechTAS). Most successful applicants for these programs are from mainland China, making up 95 percent of TTPS participants and 78 percent of TechTAS recipients. Moreover, under the Immigration Arrangements for Non-Local Graduates Scheme, Hong Kong in 2023 issued nearly 24,700 visas to mainlanders who completed their studies at Hong Kong universities, accounting for 94 percent of approved applications under that pathway that year. Many recipients relocate to Hong Kong along with their families. In the first half of 2023, Hong Kong issued nearly 48,700 dependent visas, of which 22,800 were for family members of those admitted through TTPS.

Mainland Chinese professionals leading the wave of talent migration into Hong Kong are poised to reshape the territory’s market and demographics. As of 2020, Hong Kong natives held just 30 percent of investment banking positions, with 60 percent filled by individuals from mainland China and the remainder filled by workers from abroad. As the city’s talent migration initiatives continue to welcome more mainland Chinese professionals, Hong Kong’s societal and cultural landscape is expected to undergo notable changes. Such a demographic transformation is anticipated to influence Hong Kong’s workforce composition, economic dynamics, and potentially the sociopolitical landscape.

Pull Factors for Mainland Chinese Immigrants

The influx of mainland Chinese into Hong Kong can be attributed to several pull factors. Many migrants are seeking to escape the strenuous work culture prevalent in the mainland, while also seeking better educational prospects for their children. Additionally, Chinese migrants cite higher salaries, balanced lifestyle, cosmopolitan ambiance, and wider career opportunities in Hong Kong as motivations to relocate.

In the mainland, youth unemployment has soared, with official statistics indicating a 21.3 percent unemployment rate among 16- to 24-year-olds as of June 2023, though some experts suggested the actual figure could have been close to 50 percent. With 11.6 million college graduates last May, China faces a significant mismatch in its job market, in which an abundance of highly educated young adults is contending for a relatively small number of jobs requiring their level of training. This disparity has led to instances of overqualified individuals taking on manual jobs or remaining unemployed.

In contrast, Hong Kong’s economy is famously skewed towards the professional services sector, which contributed 93 percent to gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022. Firms in Hong Kong are actively seeking to fill talent gaps. Last year, 85 percent of Hong Kong employers experienced challenges recruiting the right talent, according to the ManpowerGroup Hong Kong. Mainland graduates precisely meet the labor demand in Hong Kong. Therefore, the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce has recognized the influx of mainland Chinese professionals to Hong Kong as mutually beneficial. Well-educated mainlanders are able to build international careers and better lives, whereas Hong Kong businesses leverage their linguistic skills and cultural insights to attract Chinese investments.

Brain Drain, Brain Gain, or a Mix of Both?

The influx of mainland Chinese professionals could counterbalance the brain drain triggered by Hong Kong’s recent wave of emigration. Under the TTPS, graduates from 184 top universities, including 13 from mainland China, can apply for a visa without prior employment in Hong Kong. Although mainland universities represent a mere 7 percent of eligible institutions, those institutions’ graduates accounted for 95 percent of the 44,200 TTPS applicants in the first ten months of 2023. The government-backed HK Talent Engage committee continues to market talent initiatives to mainland professionals. Recruitment events are held in major Chinese cities such as Shanghai and Shenzhen and at top universities, signaling a deliberate strategy to attract mainland expertise.

Well-credentialed mainland professionals are expected to fuel a new brain gain and bolster the city’s economic vitality. Yet concerns abound that this changing demographic may dilute Hong Kong’s diversity, creativity, and international status. Some scholars have framed the increased interactions of populations, businesses, and politics between mainland China and Hong Kong as a socioeconomic benefit, while others fear it may encroach upon local education, housing, and the distinct Hong Kong identity. Reflecting this sentiment, 55 percent of Hong Kongers 18 to 34 years old align themselves primarily with their Hong Kong identity, according to Pew Research Center findings, whereas only 38 percent embrace a dual Hong Kong-Chinese identity. As mainland professionals continue to arrive, the blend of local and new talent may transform both the corporate sector and the fabric of society itself.

Relations with Mainland China: From Physical Integration to Population Convergence

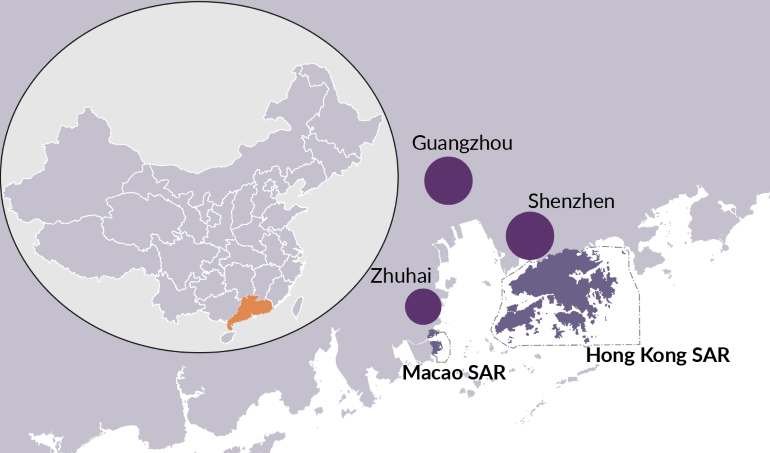

Hong Kong’s initiatives to attract Chinese talent align with the People’s Republic of China’s broader objective to integrate the city more closely with Southern China. Beijing’s efforts to blur the distinctions between Hong Kong and the mainland are epitomized by the proposal of a colossal development on the city’s periphery, dubbed the Northern Metropolis. By filling up the wetlands and creating three new artificial islands, a new business district will physically connect the Chinese cities Zhuhai and Shenzhen to Hong Kong. With an estimated budget of U.S. $75 billion, this project is poised to anchor Hong Kong within China’s Greater Bay Area, a regional cluster that also includes Macao, another special administrative region and former Portuguese colony.

Figure 3. Map of Hong Kong and Greater Bay Area

Source: MPI artist rendering.

Enhancing the region’s connectivity, the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao bridge was inaugurated in 2018. The longest sea-crossing bridge-and-tunnel system in the world, it stretches 34 miles and symbolizes the Chinese government’s commitment to linking Hong Kong to the mainland and developing a globally competitive hub akin to Silicon Valley in the United States.

More Like the Mainland, or a New Identity in the Making?

Hong Kong’s demographic and socioeconomic landscape is undergoing a considerable transformation. As the city grapples with the challenges posed by brain drain, it also is seeking to leverage the promise of brain gain. Hong Kong’s strategic efforts to attract and integrate skilled professionals signal a commitment to maintaining its economic vigor and international business prestige. Yet the influx of talent predominantly from mainland China also presents the possibility of a complex cultural and demographic shift, raising questions about diversity and the future identity of Hong Kong.

This phenomenon, coupled with top-down infrastructure developments such as the Northern Metropolis and the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao bridge, suggests Beijing is making a strategic pivot towards greater regional integration in China’s south. Intentionally or not, Hong Kong’s population swap is coming as a direct result of this strategy. As the lines between Hong Kong and the mainland blur, the city’s unique character and the freedoms coded in the Basic Law may evolve away from the one country, two systems principle. A pivot away from being a global hub to one focused on China and East Asia would bring significant change. But it may also foster a new, dynamic intercultural society. Hong Kong is no stranger to straddling multiple worlds, and its future identity remains to be seen.

Sources

BBC News. 2022. Hong Kong’s Handover: How the UK Returned It to China. June 30, 2022. Available online.

Canadian Press. 2021. Canada Opens 2 New Permanent Residency Pathways for Hong Kong Residents. Canadian Press, June 8, 2021. Available online.

Castagnone, Mia. 2023. Hong Kong’s Improved Market Conditions and Supportive Visa Schemes Spurs Jobseekers Rush from Mainland China. South China Morning Post¸ December 23, 2023. Available online.

Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), Communications and Public Relations Office. 2020. Survey Findings on Views about Emigration from Hong Kong Released by the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies at CUHK. Press release, October 6, 2020. Available online.

Corichi, Manolo and Christine Huang. 2023. How People in Hong Kong View Mainland China and Their Own Identity. Pew Research Center, December 5, 2023. Available online.

East-West Center. 2015. Can Hong Kong Escape the ‘Low-Fertility Trap’? Policy Brief No. 8, November 2015, Honolulu, East-West Center. Available online.

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. 20234. SLW Taps Talent Attraction Strategies in Shanghai Visit (with Photos). Press release, January 12, 2024. Available online.

Hamer, Lars and Laura Westbrook. 2023. Hong Kong Talent Drive: As Expats Trickle in, Wave of Mainland Chinese Sparks Concern about City’s Diversity. South China Morning Post, September 20, 2023. Available online.

Hernandez, Jon. 2022. Canada Overtakes U.K. as Destination for Hong Kong Students amid Mounting Exodus. CBC News, December 12, 2022. Available online.

Hong Kong Emigration Project. N.d. The Hong Kong Emigration Project: A Study of the Ways Hong Kongers Who Emigrate Differ from Those Who Have Considered Emigrating from Hong Kong but Have Not Yet Done So. Accessed March 18, 2024. Available online.

Hong Kong Immigration Department. 2021. Statistics on Quota Allotted under ‘Quality Migrant Admission Scheme.’ Updated February 25, 2021. Available online.

---. 2022. Introduction of Admission Schemes for Talent, Professionals and Entrepreneurs. December 23, 2022. Available online.

---. 2024. Facts and Statistics: Visas. Updated February 28, 2024. Available online.

Hong Kong Information Services Department. 2020. Safeguarding National Security in Hong Kong: The National Security Law. Updated July 7, 2020. Available online.

---. 2023. 100k Apply for Talent Schemes. July 11, 2023. Available online.

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. N.d. The Chief Executive’s 2023 Policy Address. Accessed March 18, 2024. Available online.

Hong Kong University (HKU) Business School. 2024. Hong Kong Economic Policy Green Paper 2024. Hong Kong: HKU Business School. Available online.

HR Asia. 2024. HKU Business School Unveils ‘Hong Kong Economic Policy Green Paper 2024’: Outlining Strategies in Eight Key Areas to Accelerate Hong Kong’s Economic Growth. HR Asia, January 10, 2024. Available online.

Hung, Emily. 2023. Explainer: Now or Never: Why Is Hong Kong Scrambling to Battle Record-Low Birth Rates and How Are Residents Reacting? South China Morning Post, October 26, 2023. Available online.

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). 2023. Canada Makes It Easier for Hong Kongers to Stay and Work in Canada. News release, July 11, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Permanent Residence Pathways for Hong Kong Residents: About the Public Policy. Updated August 15, 2023. Available online.

Leung, Kanis. 2023. Chinese Arrivals Replace Hong Kong Exodus. For Them, the City Is Still Freer than the Mainland. Associated Press, November 1, 2023. Available online.

Lindberg, Kari Soo. 2023. Hong Kong’s Population Rises, Reversing Years of Reporting Drops. Bloomberg News, August 15, 2023. Available online.

Lo, T. Wing, Gloria Hongyee Chan, Gabriel Kwun Wa Lee, Xin Guan, and Sharon Ingrid Kwok. 2023. Young People’s Perceptions of the Challenges and Opportunities during the Mainland China-Hong Kong Convergence. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications 10 (1): 1-14. Available online.

Reuters. 2021. Hong Kong Emigration to Britain Could Mean $36 Billion Capital Outflow. Reuters, January 14, 2021. Available online.

Rolfe, Heather and Thomas Bens. 2023. From HK to UK: Hong Kongers and Their New Lives in Britain. London: The Welcoming Committee for Hong Kongers and British Future. Available online.

South China Morning Post. 2020. Hong Kong National Security Law Full Text. July 2, 2020. Available online.

UK Home Office. 2023. How Many People Come to the UK Each Year (including Visitors)? February 23, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Immigration System Statistics, Year Ending September 2023. December 7, 2023. Available online.

---. 2024. Safe and Legal (Humanitarian) Routes to the UK. February 29, 2024. Available online.

Yeung, Cherry. 2024. Economic and Trade Information on Hong Kong. HKTDC Research, February 29, 2024. Available online.

Yu, Elaine and Selina Cheng. 2022. Hong Kong Offers Visas, Perks to Reverse Brain Drain After Losing 140,000 From Workforce. Wall Street Journal, October 19, 2022. Available online.

Yue, Ricci. 2023. Study Report on Hong Kong Migrants Recently Arrived in the UK. Liverpool: Hongkongers in Britain, University of Liverpool Department of Geography and Planning. Available online.