You are here

Indonesia: A Country Grappling with Migrant Protection at Home and Abroad

Agricultural workers in Indonesia (Photo: Peace Corps)

Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest country, has for decades been a major origin for labor migration, with its workers fanning out to locations in the Asia-Pacific and beyond. Home to a diverse array of cultures and situated along several major trading and transport routes, it has reluctantly found itself in the role of transit and destination country more recently. Though Indonesian policymakers have made progress on protecting migrant workers abroad, the country continues to face challenges associated with its competing migration identities, such as protection of trafficking victims and asylum seekers.

Migration and mobility are intrinsic characteristics of the many Indonesian cultures that shape its population of 267 million people. The country is formed by a volcanic archipelago of more than 17,000 islands, differing significantly in size, topography, and weather patterns. As a result, a high degree of seasonal inter-island travel and more permanent internal migration have often been preconditions for advancement, prosperity, and sometimes survival in the Ring of Fire.

This article explores historical and contemporary migration to, from, and through Indonesia, encompassing colonial-era movements, labor migration in the late 1900s and today, and the transiting asylum seekers who have tested regional governance and coordination.

A Bridge Between Worlds

Located between the Indian and Pacific Oceans and on some of the busiest and most economically important trade routes, such as the Straits of Malacca connecting the Middle East with East Asia, Indonesia had a history of transnational trading long before the republic’s birth in 1945. The archipelago, rich in natural resources but sparsely populated, from the 16th century onwards attracted merchants, traders, soldiers, missionaries, explorers, and adventurers in search of a better life. Particularly, the lucrative spice trade and, later, cash crops and minerals were a magnet. The Dutch East India Company was set up to control the trade, and in 1800, the Dutch government nationalized the company’s possessions, further expanding their influence in the region.

The Dutch colonizers were not the only migrants. From the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, encouraged by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the advent of steam shipping, people from the Hadhramaut, part of current-day Yemen, started migrating to the Indonesian archipelago. These migrants included preachers, teachers, spice traders, and cloth merchants. Despite intermarriage and some degree of assimilation, Chinese and Arab migrants and their descendants retained their cultural heritage, with some diasporas more visible than others, even today.

After World War II, the Netherlands tried to reclaim its colonial possessions in the region but failed against the armed forces of the young republic. At the end of the Indonesian War of Independence in 1949, 300,000 Dutch and their often Indo-Dutch families were repatriated to the Netherlands. With them also went approximately 12,500 soldiers from the Maluku Islands who had fought for the Dutch, hoping to return one day to an independent Moluccan state promised to them by the Netherlands. Only a small percentage of the remaining Eurasians (“Indos”) took up Indonesian citizenship, and over the following decade virtually the entire Dutch population left.

In the 1950s, two large exoduses happened. The new government expelled some 50,000 Dutch citizens and confiscated their businesses and properties. More than 102,000 Chinese Indonesians also left for China in the latter part of the decade due to legal uncertainty and discriminatory practices, often leaving behind their belongings involuntarily.

Over the course of the authoritarian New Order regime (1966–98), political dissidents and leaders of various independence movements in the outer provinces of Aceh, East Timor, and West Papua also left Indonesia to continue their political struggles in exile. Due to Indonesian military retaliations against these independence movements, thousands of Acehnese, Papuan, and Timorese civilians were forced to flee to neighboring countries, including Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Australia, and further afield during the respective armed conflicts in their home areas.

Indonesian Labor Heads Abroad

Indonesian labor migration to other countries—both voluntary and forced—has a long history. Historically, the traditional destination was the Malay Peninsula, just across the Straits of Malacca, but other extended destinations emerged during the Dutch colonial period for a relatively small number of migrants to other colonies, including Surinam (Dutch) and New Caledonia (French).

The scope of extended migration expanded in the 1970s, as the Indonesian government started to actively encourage international labor migration to address labor surpluses and to earn foreign currency. Most of these migrant workers went to countries in the Asia-Pacific region and the Persian Gulf, with Malaysia and Saudi Arabia consistently the most popular destinations except during short periods when the Indonesian government banned recruitment for employment in those countries. Economic turmoil that followed the 1997 Asian financial crisis also motivated many Indonesians to look for jobs abroad.

As with many other Asian countries that are sources for low-skilled labor migrants, the proportion of women grew rapidly from the 1970s onwards. With time, they outnumbered the men. Between 2006 and 2007, for example, 69 percent of low-skilled migrant workers from Indonesia were women working in countries such as Hong Kong SAR, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Middle East. Most female labor migrants are employed for domestic service, care work, and in other sectors that are often not covered by labor and employment relations laws. This makes them even more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation, as they often live and work in employers’ homes, resulting in a unique set of protection challenges.

In 2016, an estimated 9 million Indonesians worked overseas, accounting for almost 7 percent of the country’s labor force, according to the World Bank. However, this is likely an underestimate because many migrant workers are hired without authorization and avoid detection; even for authorized Indonesian workers there is no central authority that compiles numbers for all destinations.

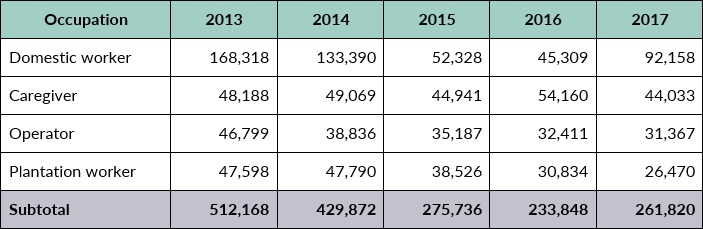

Table 1. Top Four Occupations for Indonesian Migrant Workers Recruited for Overseas Employment, 2013–17

Source: National Agency for the Placement and Protection of Indonesian Workers (BNP2TKI), “Data Penempatan dan Perlindungan TKI Periode 1 JANUARI S.D 31 DESEMBER 2017,” last updated January 17, 2018. Available online.

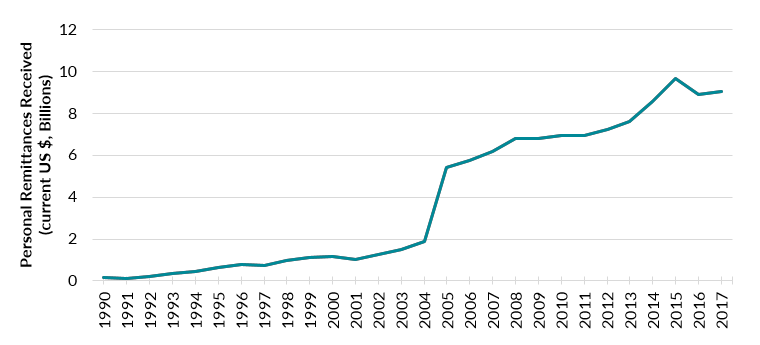

As expected, remittances began to increase as more workers went abroad; in 2017, they represented 0.8 percent of GDP (see Table 2). But so too did reports of human-rights abuses. Would-be migrants hoped for a “good employer”—someone who would pay wages and not abuse them. Indonesian officials once told departing migrants to tolerate poor treatment, but the government has become more responsive to worker needs since 1998, when the New Order’s authoritarian regime ended. Usually in response to public outrage about the physical abuse or even legal execution of migrant workers, the government has suspended recruitment to particular countries (Malaysia in 2009, lifted in 2011) and even to entire regions (the Middle East in 2015, which remained in place at this writing).

Table 2. Personal Remittances Sent to Indonesia, 1990–2017

Source: World Bank, “Personal Remittances, Received (current US$),” accessed September 13, 2018. Available online.

Indonesian migrant workers pay relatively high recruitment fees for overseas employment compared to what they earn. In Hong Kong, where the wage is deemed high, Indonesian domestic workers pay 60 percent to 70 percent of their wages in recruitment fees during the first five to seven months. This is permitted under Indonesian law; the government has not ratified the International Labor Organization (ILO) Private Employment Agencies Convention of 1998, which prohibits charging workers placement fees.

Typically, men pay the fee upfront, while women make repayments after they start work either directly (as in Hong Kong), or through deduction from their wages (Malaysia and Singapore). Repayments and deductions are often equivalent to the majority of their wages in the first year of employment—resulting in a delay of much-sought-after development impacts.

In 2017, President Joko Widodo formalized arrangements to start harnessing the economic, political, and social potential of the millions of Indonesians abroad—many of whom are no longer Indonesian citizens. For many years, the Indonesian diaspora has lobbied for legislative amendments, including dual citizenship, parliamentary representation, property ownership rights, and constitutional recognition. Presidential Regulation no. 76/2017 put into law the Diaspora Card, which provides Indonesians abroad with entitlements such as long-term visas and property ownership rights.

International Students and Marriage Migrants

Indonesia is also a source of other forms of emigration, such as international students. Historically, Australia has been the primary destination for Indonesians seeking an undergraduate degree, largely because of its proximity, high-quality education system, and English-language instruction. In 2016, almost 20,000 Indonesians studied in Australia. The United States is the second most popular destination, followed by Malaysia.

Just 7 percent of the Indonesian workforce has a college degree, and the World Bank estimates that this share would need to triple in the next few years to meet the needs of the Indonesian job market. This low rate is largely due to the lack of financially supported options, including scholarships or student loans, to pursue higher education. In 2016, for example, the Indonesian government awarded just 2,577 scholarships for postgraduate study overseas.

Indonesians also migrate for marriage, a trend seen in many Chinese-speaking areas in the Asia-Pacific region. Chinese-Indonesian women from poor backgrounds in the province of West Kalimantan are recruited to marry working-class men in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Between 1994 and 2000, the Taiwanese government issued on average 2,800 residence visas to Indonesian spouses. The women are sometimes trafficked, forcibly recruited to work in the husband’s store or for sex work. Immigration restrictions have made commercial marriage more complicated for those heading to the closest destination, Singapore, so would-be husbands instead take a short boat trip to neighboring Indonesian islands to unite with their wives and for sex tourism.

Indonesian refugees and asylum seekers are another category of outgoing migrants. Members of the Acehnese ethnic group sought international protection in neighboring Malaysia, the United States, Sweden, and elsewhere during armed conflict between the Indonesian military and the Free Aceh Movement from 1976 to 2004. Resulting from anti-Chinese riots in 1998, hundreds of Chinese-Indonesian Christians migrated to the United States (with dozens facing deportation under the Trump administration). In 2006, the Australian government granted international protection to 42 Indonesian refugees from Papua, which strained the Indonesia-Australia relationship as the Indonesian President asking the Australian Prime Minister to return the refugees. Other persecuted minorities have also claimed asylum in the region, including the Ahmadiyah in Hong Kong.

Indonesians also travel internationally for leisure and short business trips, as poverty has decreased in both rural and urban parts of the country. Significant administrative and infrastructural changes in Indonesia have encouraged this trend. The emergence of the low-cost airline Air Asia in 1996 eventually connected many Indonesian cities to its hub in Malaysia and to 130 destinations in more than 20 countries. The Indonesian government has expanded domestic airports to service international travel, and has made it easier to apply for passports. As of June 2018, Indonesians could also travel visa-free to 56 countries. But they still face substantial difficulties and costs associated with visa applications to other destinations, such as Australia and the European Union.

Immigration to Indonesia Today

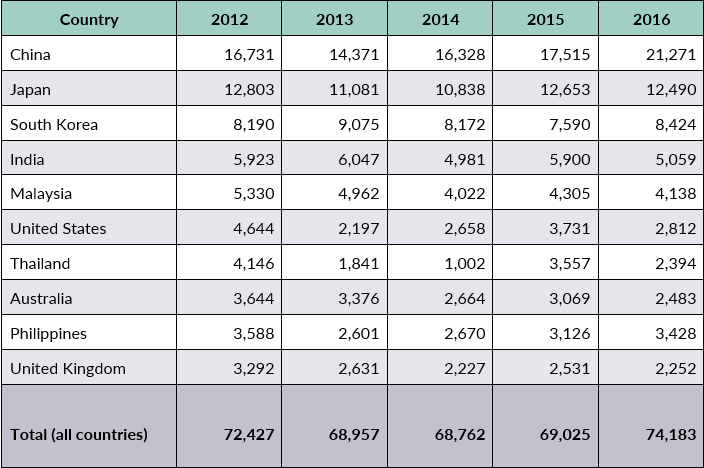

Indonesia is a destination for high-skilled migrant workers, but the government authorizes foreign employment only for positions that require qualifications, work experience, and skill sets not easily found in the domestic labor market. The number of immigrants working legally as English teachers, senior managers, and other professionals has declined in the last several years because of tighter government policies.

Table 3. Top Origin Countries and Total Number of Immigrants in Indonesia by Work Permits Issued, 2012–16

Source: Government of Indonesia, Initial Report of the Republic of Indonesia on the Implementation of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families Pursuant to the Simplified Reporting Procedure (Jakarta: Government of Indonesia). Available online.

Unauthorized low-skilled foreign workers, particularly from China, also head to Indonesia. Due to anti-China sentiment, which has not been helped by the Indonesian government’s more assertive attitude toward China in the South China Sea, this issue is often politicized and sensationalized. There has also been public outcry in response to false claims, such as that there are more than 10 million Chinese workers in Indonesia doing jobs that locals could do.

Additionally, Indonesia harbors foreign victims of trafficking, particularly fishermen from Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. In early 2015, the government rescued 1,200 stranded fishermen from Ambon and Benjina (remote locations in eastern Indonesia) where they had been kept under slavery-like conditions. Usually these individuals are repatriated to their home countries without compensation or restitution. A number of foreign women, particularly from Eastern Europe, Thailand, Vietnam, and China, also fall victim to sex trafficking. Indonesia regularly carries out deportations of arrested unauthorized migrants, deporting 7,787 people in 2016 and 11,307 in 2017.

In 2016, about 5,700 foreign students were enrolled in Indonesian educational institutions. Indonesian universities are particularly attractive to students who speak Bahasa Indonesia or Bahasa Malay, such as those from Timor-Leste (which was part of Indonesia until 2000) and Malay minorities in Southern Thailand. However, this number is very low when compared to the number of international students in neighboring Singapore and Malaysia and to Indonesians studying overseas.

Further, a 2009 agreement between Australia and Indonesia allows Australian youth ages 18 to 30 to visit Indonesia, and vice versa, to work and travel for up to two years. The quota for Indonesians to work in Australia is almost always filled. However, the initial take-up of this visa among Australians was extremely low.

Thanks to its tropical climate, Indonesia is very attractive for retirees from colder regions. In 1998, Indonesia introduced a special retirement visa for people ages 55 and older and with an income from pensions or investments of at least US $18,000 per year. Despite a number of privileges available to them, retirees may not work and must pay taxes on income earned from abroad. Unlike Malaysia, Indonesia is not among the top ten popular overseas retirement destinations.

In 2017, about 14 million foreign tourists visited Indonesia, fewer than the 15 million target set by the Tourism Ministry. Hoping to boost tourism, Indonesia offers free nonextendable visas for citizens from more than 140 countries for tourism purposes (renewable visas cost US $35). Most tourists stay for up to 30 days, as permitted under regulations, but a small number also work as consultants, reporters, or artists on multi-entry business visas and without the proper work permits.

Major Migration Policies and Ongoing Debates

The risks and repercussions for vulnerable, low-skilled labor migrants overseas are well-documented in Indonesian media and academic literature. To address these issues, in 2012 the Indonesian government ratified the 1990 UN International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICRMW), which provides a number of legal rights for migrants, including for those living and working in irregular situations.

In 2017, the Indonesian government replaced Law No. 39/2004 on the Placement and Protection of Indonesian Workers Overseas with Law No. 18/2017 on the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers. The old law did not do enough to protect the rights of migrants, rather focusing on how to administer recruitment. Under the more recent law, regional governments—instead of private companies—oversee the provision of predeparture vocational training and the placement of workers. The changes are intended to rein in private recruitment firms that charge migrants substantial fees, tying workers to them until they pay off their debt. But many observers point out that the protection of migrant workers under the new law remains weak with regard to exploitation and modern slavery.

Two other major legislative changes in the post-New Order era that are relevant to migrants are the Law on Citizenship (No. 6/2006) and the Law on Immigration (No. 6/2011). In 2006, Indonesia adopted a new Law on Citizenship, which repealed the 1958 law. Indonesia continues to apply the jus sanguinis principle, under which citizenship is conferred by having one or both parents who are citizens of the country. However, the new law introduced a limited form of dual citizenship to provide greater protection for children with parents of different nationalities. Many binational families still consider the existing policies to be insufficient, and demand amendment to the existing 2006 law to allow full dual citizenship.

In addition, Indonesia adopted a new Law on Immigration (No. 6/2011) to replace the 1992 statute. This 2011 law was designed in part to allow qualifying foreigners to more easily obtain permanent residency. It also includes provisions to facilitate coordination between police and immigration investigators, and more efficiently handle immigration violations such as human smuggling and trafficking. Two years earlier, Indonesia’s parliament ratified two international conventions on organized crime and people smuggling.

A Reluctant Receiving Country for Forced Migrants

Due to its strategic position at the crossroads between Asia and Australia, Indonesia has seen the arrival of many displaced people and asylum seekers over the last several decades. Its enormous coastline of about 34,000 miles in length is hard to patrol efficiently, allowing people to cross undetected by authorities. The relatively easy entry by boat makes Indonesia a sought-after destination for asylum seekers from the region, including Vietnam, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka.

The arrival of Indochinese refugees following the Vietnam War was the most influential event in shaping the government’s approach toward displaced groups. About 200,000 Indochinese refugees were resettled to third countries between 1975 and March 1979. However, in June 1979, nearly 43,000 Vietnamese and Cambodian “boat people” were still present in Indonesia. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) agreed to cover all costs associated with refugee centers at Galang Island, including food, education, and health care.

Shortly after the last Vietnamese departed the Galang Refugee Camps in the mid-1990s, a new group of asylum seekers started arriving: Afghans and Iranians. The first of these applied for UNHCR protection in Indonesia in 1996. Amid ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, more people set their sights on Indonesia, attracted by the easy entry requirements, low costs of living, and the opportunity to reach Australia with the help of Indonesian smugglers.

Between 1996 and mid-2013, about 58,000 asylum seekers passed through Indonesia and departed by boat to Australia. In contrast, Australia resettled about 2,000 refugees over roughly the same period. In July 2013, Australia announced that intercepted asylum seekers on boats would be accommodated in off-shore processing centers in Manus Island (Papua New-Guinea) and Nauru, and would not be able to seek asylum in Australia, as a deterrent to further migration. Moreover, with the introduction of militarized Operation Sovereign Borders in September 2013, Australia also started to turn back boats carrying potential asylum seekers to Indonesia, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka. This deterrence policy has resulted in a decreased number of attempts to travel from Indonesia to Australia irregularly by boat.

Since the arrival of the Indochinese, little has changed in Indonesia’s handling of incoming refugees: The government perceives Indonesia as a transit and not a destination country and therefore does not provide permanent refugee protection. Lacking a proper legal framework and relevant refugee policies, Indonesia continues to deny refugees important social, economic, and cultural rights while abdicating responsibility for them to third parties, such as UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). It is not a signatory to the 1951 international Refugee Convention and is unlikely to sign on. Local integration into Indonesian society is nearly impossible, and refugees continue to face prohibitions on social and economic activity.

Although resettlement prospects from Indonesia are meager, asylum seekers continue to arrive. These include members of the Hazara minority group in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as frequent arrivals of the Rohingya by boat from Myanmar, where they constitute a stateless minority and face violence and persecution by the military.

The most significant influx of Rohingya occurred during the 2015 Andaman Sea crisis, when thousands were stranded at sea. The Indonesian government tends to not want to provide much assistance to these and other transiting asylum seekers and would rather contribute humanitarian aid and diplomatic exchanges to the origin countries.

In contrast, the Indonesian people provided limited but much-needed assistance to Rohingya refugees. In two incidents in April 2018, Acehnese fishermen rescued 84 Rohingya who were stranded at sea, but whom the Indonesian and Malaysian governments refused to assist.

Trafficking, Terrorism, and Other Ongoing Issues

The geography of Indonesia—and particularly its porous maritime borders—is a major factor behind several ongoing migration challenges and opportunities facing the country.

Ongoing Challenges

The Straits of Malacca are a hotspot for the smuggling of goods and people. Asylum seekers trying to reach Australia, as well as Indonesian migrant workers returning home without passports, use the services of people smugglers to make the short but perilous crossing from southern Malaysia to the Riau Islands. The Malaysian government primarily deports Indonesian citizens who have been caught working illegally in Malaysia to Tanjung Pinang on Bintan Island, where they are known to be treated poorly by their own government. In contrast, Indonesia’s border with Singapore is less fluid, as Singaporean authorities patrol the area to prevent unwanted and illegal movements of people and goods from Indonesia.

East of Indonesia lie Malaysia, the Philippines, Palau, Timor-Leste, and Papua New Guinea. This area has been plagued by territorial disputes (for example between Indonesia and Malaysia over Ligitan and Sipadan islands), and deported migrant workers have died from preventable diseases because governments have not effectively coordinated their efforts. During the 2002 Nunukan Tragedy, for example, Malaysia deported almost 400,000 Indonesian workers to the tiny island of Nunukan, overwhelming the local population and resulting in a humanitarian crisis.

Terrorism has also been discussed in the context of international migration. Following the 2002 Bali bombings, which killed 202 people and injured another 212, the Indonesian government set up a special police unit to handle terrorism. In late 2014, around 100 Indonesians (some with spouses and children in tow) were thought to have left the country to fight for the Islamic State in Syria. As a result, some Indonesians are anxious about fighters who return from Syria and other conflict areas, such as Mindanao in the southern Philippines. These individuals are seen as potential troublemakers and some have been linked (falsely) to suicide attacks in 2018 in Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-largest city.

Solidifying Opportunities

Amid rising interest in intraregional mobility and the recognition of need for a stronger protection infrastructure for workers abroad, Indonesia is presented with some opportunities. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Economic Community (AEC) was launched at the end of 2015, aiming to facilitate the movement of labor in Southeast Asia. The AEC is not as ambitious as the European Union and focuses on high-skilled migrants and professionals who travel for business, for example, to scope export markets for their products. The AEC has not made it easier for the majority of Indonesia’s low-skilled migrant workers to move around the region.

In 2017, the Indonesian government made significant efforts to safeguard the rights of migrant workers. In October, Parliament passed Law No. 17 on the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers, which draws heavily on protection principles enshrined in the ICRMW. In the lead-up to November 2017, when ASEAN governments signed an agreement on how they should protect the rights of migrant workers, the Indonesian government strongly (and ultimately unsuccessfully) advocated that the instrument should be legally binding for all signatories.

Challenges on the Horizon

For many years, observers and Indonesian policymakers overlooked the country’s migration roles other than as an origin of migrants. As a result, the Indonesian government has focused almost exclusively on emigration, having progressively developed mechanisms to better protect the human rights of Indonesian workers abroad. But Indonesia is in fact also a destination and place of transit for migrants. The government has not given equal attention to protecting immigrants, including migrant workers with permits, asylum seekers, victims of trafficking, and others living and working in irregular situations, as required by the ICRMW.

Nationalist sentiment and nativism are on the rise in Indonesia, which partly explain why the government is so comfortable prioritizing the protection of Indonesian migrants over foreigners. These attitudes have been directed at the relatively small number of foreign workers in the country, including migrants from mainland China found to be working on China-funded development projects in Java and Sulawesi. In 2018, there was also a backlash against the government after it announced a plan to recruit immigrants to work in higher education, as part of a wider strategy to promote competition and innovation in teaching and research. The plan stands in contrast to the government’s largely protectionist approach to managing the country’s economy and natural resources.

Climate change is another impending challenge. Some inhabited islands might disappear under water, while other parts of Indonesia may become uninhabitable because of drought. Moreover, Indonesia is the world’s fifth largest emitter of greenhouse gases, mostly produced by forest fires as commercial actors convert forests and carbon-rich peatlands into plantations. Between 50 million and 60 million Indonesians depend on these forests for their survival, some of whom are pushed to seek alternative livelihoods by moving internally or abroad.

By 2030, 70 percent of Indonesia’s population is projected to be of working age, presenting an opportunity and a test for the country. The main benefit to society would be in the case that Indonesians are able to live more prosperously at home by working and earning an income. But this hinges on the creation of enough gainful employment opportunities for the 2 million or so workers who enter the job market each year. Indeed, fewer migrant workers are leaving the country today for low-skilled employment such as domestic work, because they can find work in these occupations at home—though it remains to be seen whether Indonesia’s overall economic growth can keep pace with its labor market.

Sources

Aji, Priasto. 2015. Summary of Indonesia’s Poverty Analysis. Manila: Asian Development Bank. Available online.

Amnesty International. 2015. Deadly Journeys: The Refugee and Trafficking Crisis in Southeast Asia. London: Amnesty International. Available online.

Crouch, Melissa and Antje Missbach. 2013. Trials of People Smugglers in Indonesia: 2007-2012. Melbourne: Centre for Indonesian Law, Islam, and Society. Available online.

Ford, Michele and Lenore Lyons. 2013. Outsourcing Border Security: NGO Involvement in the Monitoring, Processing and Assistance of Indonesian Nationals Returning Illegally by Sea. Contemporary Southeast Asia 35 (2): 215–34.

Government of Indonesia. 2017. Initial Report of the Republic of Indonesia on the Implementation of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families Pursuant to the Simplified Reporting Procedure. Jakarta: Government of Indonesia. Available online.

Harijanti, Susi Dwi. 2017. Report on Citizenship Law: Indonesia. Florence: European University Institute. Available online.

Higher Education Marketing. 2018. Recruiting International Students from Indonesia. Blog post, January 10, 2018. Available online.

Hugo, Graeme. 1993. Indonesian Labour Migration to Malaysia: Trends and Policy Implications. Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 21 (1): 36-70.

Jones, Sidney. 2000. Making Money off Migrants: The Indonesian Exodus to Malaysia. Wollongong, N.S.W.: Capstrans, University of Wollongong.

Jones, Sidney and Solahudin. 2015. ISIS in Indonesia. Southeast Asian Affairs: 154–163.

Kaur, Amarjit. 2005. Indonesian Migrant Workers in Malaysia: From Preferred Migrants to ‘Last to Be Hired’ Workers. RIMA: Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs 39 (2): 3–30.

Killias, Olivia. 2018. Follow the Maid: Domestic Worker Migration from Indonesia. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Press.

Lindquist, Johan. 2010. Labour Recruitment, Circuits of Capital, and Gendered Mobility: Reconceptualizing the Indonesian Migration Industry. Pacific Affairs 83 (1): 115–32.

Lukman, Enricko. 2016. Government Hopes More Foreign Students Will Study at Indonesian Universities. Indonesia Expat, March 7, 2016. Available online.

McNevin, Anne. 2014. Beyond Territoriality: Rethinking Human Mobility, Border Security, and Geopolitical Space from the Indonesian Island of Bintan. Security Dialogue 45 (3): 295–310.

McNevin, Anne and Antje Missbach. 2018. Hospitality as a Horizon of Aspiration (or, What the International Refugee Regime Can Learn from Acehnese Fishermen). Journal of Refugee Studies 12, March 2018. Available online.

Missbach, Antje. 2012. Separatist Conflict in Indonesia: The Long-Distance Politics of the Acehnese Diaspora. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

---. 2015. Troubled Transit: Asylum Seekers Stuck in Indonesia. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

National Agency for the Placement and Protection of Indonesian Workers (BNP2TKI). 2017. Data Penempatan dan Perlindungan TKI Periode 1 JANUARI S.D 31 DESEMBER 2017. Last updated January 17, 2018. Available online.

---. 2017. Data on the 2016 Placement and Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers. Updated February 8, 2017. Available online.

Palmer, Wayne. 2016. Indonesia’s Overseas Labour Migration Programme, 1969-2010. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill.

Palmer, Wayne and Antje Missbach. 2018. Enforcing Labour Rights of Irregular Migrants in Indonesia. Third World Quarterly. [DOI 10.1080/01436597.2018.1522586].

---. 2018. Back Pay for Trafficked Migrant Workers: An Indonesian Case Study. International Migration 56 (2): 56–67.

Phillips, Janet and Harriet Spinks. 2013. Boat Arrivals in Australia since 1976. Canberra, Australia: Parliament of Australia. Available online.

Setijadi, Charlotte. 2017. Trends in Southeast Asia: Harnessing the Potential of the Indonesian Diaspora. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

Silvey, Rachel. 2007. Mobilizing Piety: Gendered Morality and Indonesian–Saudi Transnational Migration. Mobilities 2 (2): 219-29.

Sugiyarto, Guntur and Dovelyn Rannveig Mendoza. 2014. A “Freer” Flow of Skilled Labour within ASEAN: Aspirations, Opportunities, and Challenges in 2015 and Beyond. Bangkok and Washington, DC: Asian Development Bank and Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Tarmizi, Hendarsyah. 2018. Commentary: Are We Heading toward Demographic Bonus or Disaster? Jakarta Post, March 5, 2018. Available online.

Tirtosudarmo, Riwanto. 2015. On the Politics of Migration: Indonesia and Beyond. Jakarta LIPI Press.

Weiss, Meredith L. and Michele Ford. 2011. Temporary Transnationals: Southeast Asian Students in Australia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 41 (2): 229–48.

World Bank. 2017. Indonesia’s Global Workers: Juggling Opportunities & Risks. Washington, DC: World Bank.

---. N.d. Personal Remittances, Received (current US$). Accessed September 13, 2018. Available online.

World Resources Institute. N.d. Forests and Landscapes in Indonesia. Accessed August 2, 2018. Available online.