You are here

Iran Faces Dwindling Water and Escalating Climate Pressures, Aggravating Displacement Threats

Afghan refugees in Iran's Semnan refugee settlement. (Photo: © UNHCR/Hossein Eidizadeh)

Drought, floods, and extreme weather have had devastating effects on Iran, forcing people to move internally, affecting one of the world’s largest populations of displaced people (mostly Afghans who have sought refuge in the country), and likely propelling emigration. More than 11 million people in Iran were affected by floods from 1980 to 2000. In recent years, tens of thousands of people annually—and as many as 520,000 in the midst of devastating flash floods in 2019—have been displaced internally by natural disasters. In January, the government said that approximately 800,000 Iranians had been internally displaced due issues related to climate change.

In This Article

Nearly 85 percent of Iran is in an arid or semi-arid zone, meaning that even as millions are confronted by deluges, many also face a lack of water and heightened vulnerability to droughts. Extreme weather such as a paralyzing 2023 heatwave, which led to a two-day nationwide shutdown and a heat index as high as 158 degrees Fahrenheit (70 degrees Celsius), can further aggravate the situation.

It is possible that internal displacement is spurring movement outside Iran, although there is little direct evidence at present. For some Iranians, environmental challenges may provide sufficient reason to migrate, often to destinations in Europe via neighboring Turkey, or elsewhere. This migration may occur in direct response to climatic pressures, such as displacement by flooding. But it may also happen indirectly, through economic forces, with farmers compelled to leave barren lands and herders forced to abandon their life of animal husbandry.

Disputes over dwindling water supplies also sometimes turn into serious conflict and political tensions, as the consequences of drought are magnified by Iran’s swelling population, which has approximately doubled over the last 40 years, to 89 million in 2022. Large protests over water shortages in the southwest province of Khuzestan in mid-2021 may be a sign of things to come, as residents turn their frustration on the government. As more people undertake rural-to-urban migration within the country, residents in Iran’s cities likely will see new arrivals as competition for jobs, housing, and other resources.

Environmental hazards are a problem for many immigrants residing in Iran, large numbers of whom were displaced from Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. Ironically, many of the 3.4 million refugees and other forced migrants in Iran arrived after fleeing conflicts and economic crises that were aggravated by environmental degradation in their own countries. Intense drought and flooding in Afghanistan, one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries, have contributed to a major and debilitating humanitarian crisis. In Iran, refugees in some settlements faced challenges during the 2023 heatwave, including limited access to water and affordable, nutritious food. Due to restrictions on their mobility, many refugees and other migrants are confined to areas of the country that are the most vulnerable to climate impacts. Efforts to mitigate the impacts of climate change have likely been impaired by international sanctions against Iran.

As a result, there will likely be more internal migration within Iran, and, over the long run, a higher likelihood of emigration. This article provides an overview of the major climatic challenges in Iran, their impacts on natives and migrants, and efforts to adapt to those hazards.

Special Issue: Climate Change and Migration

This article is part of a special series about climate change and migration.

Scarce Water Supplies Pose Challenges for Agriculture and Other Sectors

A consistent challenge is scarcity of water, which seems to be compelling internal migration within Iran and, potentially, movement out of the country. In 2023, 200 members of Iran’s Parliament warned that supplies would run out in a matter of weeks and create a humanitarian disaster, although this proved not to transpire. Water cuts were reported even in Tehran.

Iran has struggled with water availability for years, but the situation is growing increasingly dire. The country uses approximately 83 percent of all available freshwater resources, about twice as much as international standards say is sustainable. Part of this is because of the way that the resource is managed. Approximately 90 percent of water went to agriculture as of 2017, which accounted for only about 13 percent of the economy as of 2022. Yet the sector holds a special place for the country; after the 1979 revolution and resulting international isolation, political leaders viewed agricultural self-sufficiency as key to Iran’s future and doubled down on being able to feed everyone in the country without importing food.

Boosting the country’s water productivity and improving water efficiency are current priorities for international organizations operating in Iran, such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. A project in the northwestern Qazvin province, for instance, is focused on enhancing water accounting and productivity. However, analysts insist that technical capacity-building is not sufficient on its own and must be paired with other interventions, such as offering cash to people in water-intensive industries to help them transition to another industry or weather the lean times. While adaptations to farm and garden irrigation systems will take time, many landlords and farmers will be hesitant to make the change. Temporary financial support could tide them over until lands are ready for the next agriculture cycle. Otherwise, they may be drawn to other parts of the country, where they may find more sustainable livelihoods.

Another approach is to change the use of lands and farms in specific districts in order to ensure environmental compatibility. Offering business grants and similar support programs could help individuals transition smoothly from farming to an alternative business without having to move to cities or abroad.

River Disputes

Water resource management is not just an agricultural issue. Iran is involved in disputes around water rights with neighboring Afghanistan, Iraq, and Turkey, which have grown into increasingly bitter feuds that have repercussions for migrants. In part, the standoffs hinge on the construction of huge dams to enhance control over water flows and usage. There were 188 dams in the Islamic Republic of Iran as of the end of 2021. While these dams may help divert and manage water, they also result in the drying up of wetlands and lakes, and have had major impacts on farmlands and local residents, not to mention wildlife such as migratory birds. These impacts are felt both in Iran as well as in neighboring nations in which communities depend on the water.

Government officials have been unable to strike agreements on management of the Aras River (which flows from Turkey to form Iran’s border with Armenia and Azerbaijan), the Arvand (which flows from the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers to the Persian Gulf and comprises some of the Iran-Iraq border), and the Helmand (which flows from Afghanistan). At times these disputes have turned deadly, such as in a May 2023 shooting involving Iranian border guards and a Taliban fighter. Escalating water tensions contributed to Iran’s recent crackdown on unauthorized Afghan immigrants, described in more detail below.

The situation seems primed for UN organizations to take steps for dispute resolution. Failure to resolve these tensions could aggravative underlying social frictions, potentially spurring further violence and displacement. At the same time, Iran will need assistance in developing its technical capacity for purifying seawater from the Persian Gulf. Yet wide-ranging economic sanctions on the country make it impossible to implement such an effort.

Will Water Pressures Lead to Heightened Migration?

Among the most climate-vulnerable areas of Iran are those in the country’s center, including the provinces of Fars, Isfahan, Kerman, Semnan, and Yazd. These regions are in or near two large deserts: Dasht-e-Loot and Dasht-e-Kavir. Meanwhile, provinces in the north such as Gilan, Golestan, and Mazandaran lie between the Caspian Sea and the Alborz mountain range. They tend to have more plentiful water, cooler weather, and more fertile land. As such, these northern regions have become increasingly attractive for internal migrants pushed out by harsh conditions elsewhere. According to the government, approximately 800,000 people moved to Mazandaran between 2021 and 2023, many from climate-affected regions.

Yet resources in these provinces are not sufficient to meet the needs of all newcomers in terms of jobs, housing, health care, food, and water. As these regions’ populations increase, so too do the demands on natural resources. This could lead to water shortages, officials warn, and long-term imbalances as land previously used for farming and other purposes is converted into housing and other construction. “The question will be raised… how to provide the new population with essential services such as water, gas, telephone, education, and treatment?” former MP Gholam Ali Jafarzadeh Imanabadi said in 2017. “The soil of Gilan is cheap and suitable for agricultural activities, however, some migrants have turned these soils and lands into housing.”

The limited capacity to provide livelihood alternatives and basic accommodation internally could cause an overflow internationally. In recent years, the number of humanitarian migrants from Iran has steadily increased, although a significant share of this trend is due to the country’s political environment and international isolation. There were more than 225,000 Iranian refugees and asylum seekers in other countries in 2023, more than double the 104,000 in 2013, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Increased migration out of Iran could pass through Turkey and on to European Union countries, which are a common destination for Iranian migrants. More than 1.3 million Iranians lived abroad as of 2020, according to UN data, with the largest numbers in the United States (387,000), Canada (166,000), Germany (153,000), and Turkey and the United Kingdom (84,000 each).

Migrants in Iran Face Climate Extremes and Pressure

Iran is a country of transit and destination for migrants from the Middle East and South Asia, due to its geopolitics, demographics, and economic opportunities. The 3.4 million refugees living in Iran as of October 2023 were the joint largest population globally, tied with Turkey, according to UNHCR. Another 1.1 million Afghans lack legal status or hold a resident permit or an Afghan family passport. Changing environmental conditions in Iran are already impacting these displaced individuals and will be linked to future migration.

Approximately 1 million Afghans fled to Iran in the aftermath of the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in 2021, according to the Iranian government, many arriving through irregular channels. Many fled persecution or civil unrest in Afghanistan, but more than one-quarter of those surveyed by UNHCR said they were also leaving for economic reasons, which for farmers and herders may include consequences of climate change.

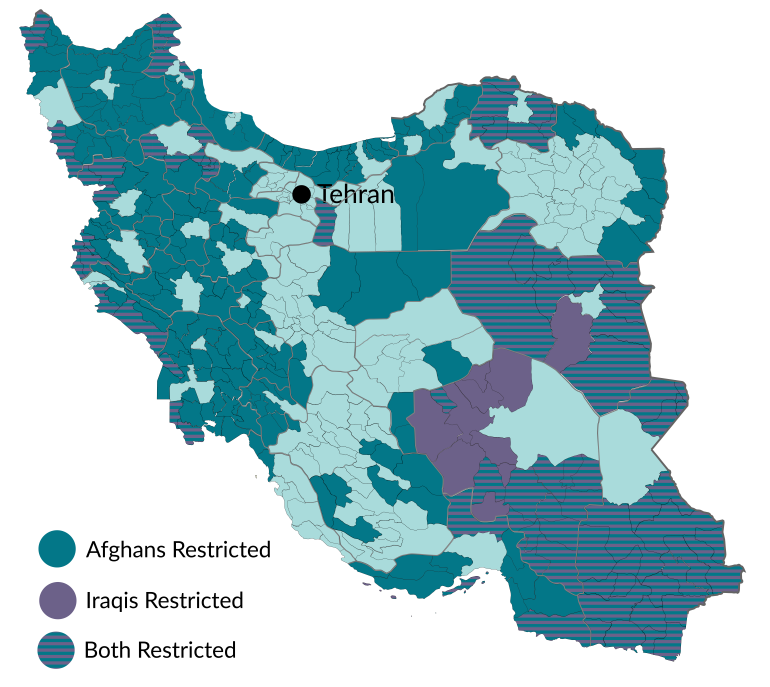

Many Afghans and Iraqis in Iran face mobility restrictions that prevent them from residing outside the highly arid central area (see Figure 1). This both exposes individuals to environmental hazards and limits their ability to move internally, potentially raising the prospect of onward international migration.

Figure 1. Iranian Districts Off-Limits to Afghan and Iraqi Immigrants, 2022

Note: Map shows “no-go districts” for holders of Amayesh and Hoviat cards, which are for Afghan and Iraqi nationals, respectively.

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) artist rendering based on UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “What Are the Movement Restrictions for Afghan and Iraqi Nationals in Iran?” September 19, 2022, available online.

In September, the Iranian government declared that Afghans living in the country without authorization would be sent back, as tensions continued to escalate with Afghanistan over water rights and other issues. Tehran has also claimed that international support for the refugee population is too meager in relation to the demands. Approximately 345,000 Afghans were deported from Iran over a three-month period after that announcement, Afghan leaders said.

Need to Adapt, but Hobbled by Sanctions

A red warning light is going off in Iran. The country is facing extreme drought, heat, and floods, and is a major destination for migrants fleeing conflict, environmental devastation, and other crises. But as Iran deals with a combination of increasingly dire environmental hazards, it is struggling to accommodate new arrivals—including those moving within the country. Many Afghan refugees and other migrants in Iran are eager to move onward, either through the formal resettlement process or by their own means. Because they are often stuck in climate-affected areas due to geographic restrictions imposed by the government, their present challenges and future prospects become all the more severe.

The West’s longstanding efforts to isolate Iran over its nuclear program and support for regional militant groups is also complicating the picture. Tensions flared anew in recent months, as Iran-backed militias attacked U.S. forces in Iraq, Jordan, and elsewhere in a region further inflamed by Israel’s military operation in Gaza.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was ratified by 198 parties, declares that “developed country Parties… shall… assist the developing country Parties that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in meeting the costs of adaptation to those adverse effects.” In Iran, however, this situation is complicated by the Western world’s approach towards Tehran and the country’s general diplomatic isolation.

Moreover, Iran is among the world’s top ten carbon-emitting countries (although its emissions are a fraction of those of the largest emitters: China and the United States). While the government is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it has struggled to do so, in part because Western sanctions against the country are preventing it from increasing its technical capacity and energy efficiency. For instance, Iran has a problem replacing its oil-based industry, and the quality of its gasoline tends to be quite below international standards. The sanctions and their consequent economic challenges have pushed the government to trade energy with neighbors such as Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan, which are highly dependent on Iran’s electricity, gas, and oil. Thus, the whole region faces further headwinds moving in a more environmentally sustainable direction.

Greater diplomatic engagement could help on all these fronts. Assistance with policymaking and technical capacity-building could aid Iran’s ability to adapt to climate pressures, respond to the influx of migrants in some areas, and make it easier for people in climate-vulnerable regions to remain in place. While it remains highly unlikely in the current geopolitical environment, international funding for Iran could help dampen the effect of climate pressures and accommodate vulnerable migrants.

At the heart of any programs, however, should be farmers, businesses, local residents, and other people directly impacted by the consequences of climate change. Efforts to address climate change and adapt to its impacts would help prevent future displacement in a country that already is a major host of forced migrants.

Sources

Ahwaz Human Rights Organization. 2019. Ahwaz Floods; Save Half a Million Displaced in 274 Villages Evacuated! May 2, 2019. Available online.

BBC News. 2018. Iran Unrest: "Ten Dead" in Further Protests Overnight. January 1, 2018. Available online.

Brussels International Center for Research and Human Rights (BIC). 2019. Iran and Climate Refugees: An Alarming Situation. Brussels: BIC. Available online.

Diyarmirza News. 2018. تغییر مقصد مهاجران بهسمت «شمال» و افزایش ۲۰درصدی جمعیت مناطق شمالی. October 26, 2018. Available online.

Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR). 2023. GHG Emissions of All World Countries: 2023 Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online.

Enerdata. 2022. Iran Energy Report. Grenoble, France: Enerdata.

Gul, Ayaz. 2023. Taliban: Iran Deports Almost 350,000 Afghans within 3 Months. Voice of America, December 11, 2023. Available online.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2023. IDMC Data Portal. Updated November 15, 2023. Available online.

Iran Newspaper. 2023. ذوق مهاجرت به «مازندران. August 15, 2023. Available online.

Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA). 2024. Some 800k Iranians Displaced Due to Climate Change: Official. January 29, 2024. Available online.

Livingston, Ian. 2023. Hot-Tub-Like Persian Gulf Fuels 158-Degree Heat Index in Iran. The Washington Post, August 9, 2023. Available online.

Madani, Kaveh. 2014. Water Management in Iran: What Is Causing the Looming Crisis? Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 4: 315-28. Available online.

---. 2021. Have International Sanctions Impacted Iran’s Environment? World 2 (2): 231-52. Available online.

Meneghetti, Luisa. 2019. Flash Floods Submerge 90% of Iran: Could the Devastation Have Been Avoided? IDMC, May 23, 2019. Available online.

Moridi, Ali. 2017. State of Water Resources in Iran. International Journal of Hydrology 1: 111-14. Available online.

Statistical Centre of Iran. 2019. Iran Statistical Yearbook 1397 (2018 – 2019). Tehran: Statistical Centre of Iran. Available online.

United Nations in Islamic Republic of Iran. 2021, Boosting Water Productivity and Improving Water Efficiency in Qazvin Irrigation Network in Iran Despite the COVID-19 Pandemic. March 15, 2021. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. What Are the Movement Restrictions for Afghan and Iraqi Nationals in Iran? September 19, 2022. Available online.

---. 2023. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2022. Copenhagen: UNHCR Statistics and Demographics Section. Available online.

---. 2023. Refugee Data Finder. Updated October 24, 2023. Available online.

World Resources Institute (WRI). 2015. Islamic Republic of Iran: Intended Nationally Determined Contribution. Washington, DC: WRI. Available online.

Yee, Vivian and Leily Nikounazar. 2023. In Iran, Some Are Chasing the Last Drops of Water. The New York Times, June 21, 2023. Available online.