You are here

Post-Soviet Labor Migrants in Russia Face New Questions amid War in Ukraine

A migrant from Tajikistan outside Moscow. (Photo: © ILO / Marcel Crozet)

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has shifted the decision-making of immigrants and would-be immigrants to Russia from involving primarily financial issues to those that are increasingly moral and security-laden. The war has complicated questions for the millions of individuals from former Soviet states in Central Asia who have long met Russian labor demands, particularly in low-paying industries that do not require high levels of education. Importantly, most of these immigrants (typically from countries including Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) are young adult men, which has made them targets for recruitment and conscription by Russia’s military, which has faced significant battlefield casualties in Ukraine.

In recent months, these post-Soviet migrants have had to reckon with questions about supporting a country condemned by much of the world—one that may coerce them into military service and where the economy has been affected by sanctions. Moscow recently eased the pathway to citizenship for many of these immigrants, whose families and origin communities often depend on remittances. In 2021, more than $16.8 billion was remitted via formal channels from Russia, much of it to countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, where remittances accounted for approximately one-third of gross domestic product (GDP), according to the World Bank. Money transfers to Central Asia increased in 2022, due in part to the demand for migrant workers, booming oil prices, and appreciation of the ruble against the U.S. dollar.

Historically, labor migration to Russia has been robust, and new arrivals have been integral to the Russian economy. Immigration proved surprisingly resilient to shocks following Russia’s economic recovery of the 2000s, in part because many newly independent countries in Eurasia were left with unequally distributed resources and production facilities following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The shared Soviet past created a post-colonial environment in which migrants from Central Asia found in Russia cultural and legal familiarity as well as economic opportunity. Meanwhile, Russia’s population growth has depended on permanent flows of new citizens, as native Russians experience a declining fertility rate and relatively low life expectancy.

The war has complicated migrants’ typically pragmatic orientation and it is unclear whether Russia-favorable migration patterns will persist. Beyond concerns about Russia’s geopolitical troubles and the potential to be conscripted into a bloody war, some migrants and other Central Asians have expressed moral outrage at Russia’s continued insistence on domination—a feeling stoked by the experience of subservience to Moscow during the Soviet era. While Russian citizenship may now be easier to access, migrants nonetheless face uncertain legal terrain and unpredictable immigration enforcement. These dynamics have created a complex situation, pulling migrants in multiple directions.

This article reviews the changing policies and experiences for migrants from post-Soviet countries, particularly in Central Asia, following the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Migration in the Shadow of War

Western sanctions followed Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, triggering a financial crisis that impacted migrants in Russia. At the time, the Kremlin sent ambivalent messages to the public, large portions of which expressed skepticism of migrants similar to that seen in many immigrant-receiving countries. Witnessing an apparent precipitous drop from 3 million official labor migrants in 2014 to 1.8 million in 2015, after the invasion of Crimea, the Kremlin chose a risky strategy of attributing the change to the economic crisis. This move relied on a rally-around-the-flag effect, trusting the public would support Moscow’s efforts in Ukraine regardless of the consequences.

In fact, evidence suggests the statistical decline was the result of a change in immigration policy that simply issued fewer documents to labor migrants. The number of foreign nationals entering the country actually increased, and many migrants simply muddled through the 2014 economic crisis. While wages in Russia were lower than they had been, they were still higher than what many migrants could earn in their origin countries. And by this time, migration was entangled in family traditions and life-cycle achievements such as paying for a car, house, or wedding, making it difficult to abandon. For many, Ukraine was just one of many frozen conflicts in the region, including in Azerbaijan and Georgia.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 changed this sleepy sense of security. Russian authorities immediately clamped down on media and public commentary, obscuring criticism and the scale of the conflict. The media space in Central Asia, however, was comparatively much freer and more reliable, allowing migrants to learn about the fighting through their networks. This led to a sort of post-colonial and anti-imperial solidarity among non-Russians that influenced many Central Asians’ responses to the war.

Migrants in Combat

For migrants, the invasion manifested in a multitude of ways. While some migrants were driven by moral considerations to avoid Russia, others remained pragmatically focused on economics, predicting greater opportunities as a result of Russian men going to war or leaving the country to avoid conscription. Instead, foreign workers remaining in Russia have been subjected to increased security, scapegoating, and direct recruitment to join the war effort.

Early on, there were scattered reports of Central Asians fighting for the Russian army in Ukraine, and rumors circulated they were being offered easier access to citizenship in exchange for enlisting. At the time, there was no legal basis for this type of promise, and many suspected the military was using false pretenses to lure migrants into service. However, Russian law was changed in September 2022 to streamline access to citizenship for foreign nationals who serve in the military. A military recruitment office opened directly adjacent to Moscow's main migration center. Migrants have attested to being pressured, tricked, and even tortured into signing military contracts.

The lure of Russian citizenship for some migrants is attractive, though without reliable statistics it is impossible to disentangle who enlisted voluntarily and who was coerced, or even the total number of foreign enlistments. The mobilization of migrants and Russian citizens from minority groups (such as Buryats and Dagestanis) suggests that both citizenship and non-Slavic ethnic identity are increasingly liabilities for conscription. Instead of offering migrants secure legal status, the prospect of citizenship now may include a path to a war zone.

While expanding citizenship opportunities to Central Asians remains a separate strategy from the “passportization” that Russia uses in contested territories, which gives the government an excuse to use force to protect its recently minted citizens abroad, both are examples of increasingly weaponized citizenship policy. Similarly, other areas of Russia’s migration policy are increasingly securitized. In October 2022, two Tajik nationals opened fire at a military training center in Belgorod, near the Ukrainian border, killing 11 people, in the most violent and mysterious incident involving interethnic conflict within the Russian military in years. The shooting allegedly followed a religious dispute, when Tajik recruits were prohibited from praying according to their traditions, and took place just a week after a summit in which Tajik President Emomali Rahmon urged Russian President Vladimir Putin to “respect” Central Asia, an episode interpreted as either unprecedented criticism of Russia or a plea for more attention.

It is common in Russian media and politics to refer to episodes such as the Belgorod shooting in a way that paints migrants as a security risk. Western media outlets sometimes frame these episodes as acts of protest against an overly dominant Russia. But realities are much more complex, involving the motives and actions of many people on the ground. Days after the shooting, which the Russian government has described as a terrorist attack, Putin met with Russia’s Security Council to discuss a new security agenda that increased scrutiny on migrants, including by stepping up raids and surveillance to discover migration violations.

Ukrainians in Russia: The Migrants the Kremlin Wants

Scholars and activists point out that racial discrimination and imperial mentalities persist in Russia. These have come to the fore amid the invasion of Ukraine, which represents an egregious violation both of international law and of respect for group self-identification. Russia’s migration sphere, however, demonstrates some nuances, especially in how Slavic migrants (including Ukrainians) are treated differently than Central Asians.

Separatist conflict in the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk beginning in 2014, around the time of Crimea’s annexation, sent a wave of migrants eastward into Russia. Leaders quickly responded by erecting shelters throughout Russia and providing temporarily transportation and emergency funds to displaced Ukrainians. Legal pathways to citizenship were also simplified for the displaced, Russian speakers, and “compatriots,” a loose analogue for ethnic kin. Ukrainians have not been the only ones able to benefit from these changes, but authorities clearly had them top of mind. (These legal mechanisms are separate from those used to issue Russian passports to Ukrainians living in disputed territories, which also began in 2014.)

In practice, many Ukrainians found the procedures difficult or did not want to settle in the regions the programs allowed, and instead sought legal status as labor migrants. This has blurred the lines between migrant categories, making it difficult to have a clear picture of the patterns. Still, the number of Ukrainians entering Russia increased by several million per year beginning in 2014.

With Russia’s full-scale attack in 2022, these trends continued; nearly 2.9 million Ukrainians went to Russia in the year following the invasion, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), some out of desperation, some in solidarity with Moscow, and some—including thousands of children—reportedly by force. Legal changes were intended to facilitate this movement and subsequent naturalization.

On the ground, volunteers provided assistance to Ukrainians fleeing eastward. Some newly arriving Ukrainians immediately sought escape westward, back into Ukraine or the European Union. These flows are difficult to quantify and are entangled with stories of trauma, forced deportation, and kidnapping.

While those from Ukraine have been the target of preferential Russian laws and policies, giving them a seeming advantage over Central Asian immigrants, they face similar bureaucratic difficulties and can have trouble legalizing their status. Nevertheless, they tend not to face the everyday discrimination that Central Asian migrants often encounter.

Russia’s Growing Ties with Former Soviet Neighbors

Russia now faces a paradox in which it depends on migrants to bolster its economy and offset demographic challenges, yet simultaneously exploits many of them by holding them in inferior social positions and coercing some into military service. This situation has been long in the making.

Migration flows within the post-Soviet system are characterized by historical relationships, legacies of both the Russian Empire and Soviet Union, and a shared language, culture, and legal norms. Non-Russian citizens of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—have visa-free access to Russia and can obtain permission to work upon arrival (Ukrainians are also included in these measures although their country is not officially in the bloc). Other countries in the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU)—Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan—have the right to employment in Russia without obtaining a work permit. Migration from these countries measures in the millions, though trends are somewhat difficult to track.

Migrants utilize a variety of legal avenues to allow them to work, while a substantial (if unknown) number work without authorization. Those from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan can enter Russia visa-free and obtain labor “patents” upon arrival. Before 2015, when patents became the only type of labor document for CIS citizens, migrants could choose between a year-long work permit, limited by regional quotas, and a relatively easier to obtain patent, which could be purchased monthly through a minimally bureaucratic process.

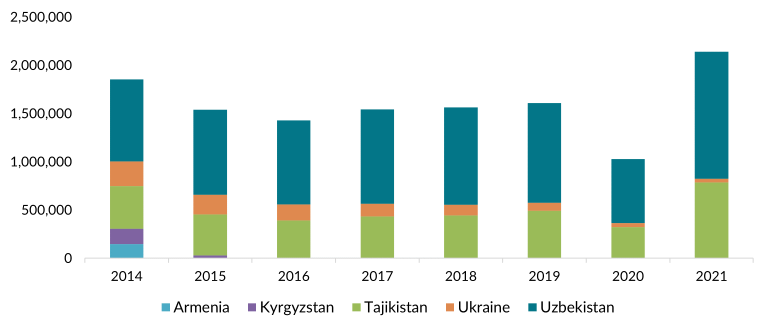

Figure 1. Immigrants in Russia with a Work Patent, for Select Major Countries of Origin, 2014-21

Note: Citizens of Eurasian Economic Union Member States do not need labor patents to work legally in Russia, so issuance to Armenians and Kyrgyzstanis declined once the union was formed in 2015.

Source: Author’s analysis based on data from Russia’s Federal State Statistics Service; TASS, “Граждане Узбекистана в 2021 году оформили наибольшее число патентов на работу в России,” TASS, February 6, 2022, available online.

When Armenia and Kyrgyzstan joined the Eurasian Economic Union in 2015, their citizens no longer needed to purchase labor patents and could work with just an employment contract.

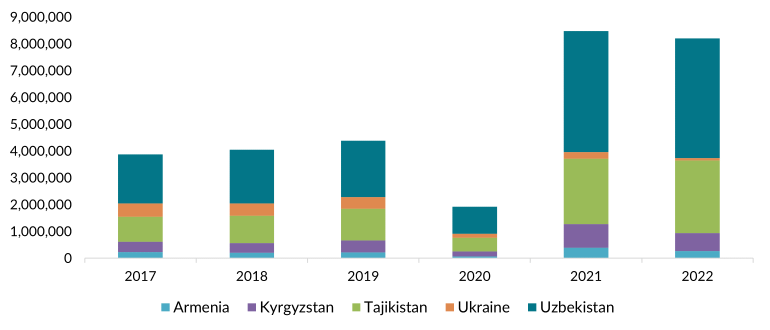

Discrepancies in the data show many more migrants declare intention to work upon entering Russia than obtain necessary legal documents to do so, suggesting that despite the legal pathways there is a large population of migrants without legal status or working informally. For instance, approximately 364,000 migrants from Kyrgyzstan and 139,000 from Armenia submitted labor contracts to secure official status in 2021, far below the 884,000 Kyrgyz and 390,000 Armenians who had registered their residence in Russia after declaring an intention to work. Meanwhile, 4.5 million Uzbeks registered intention to work in 2021 but just 1.3 million received patents. Similar gaps exist among all countries of origin.

Figure 2. Residence Registrations of Immigrants Intending to Work in Russia, for Select Major Countries of Origin, 2017-22

Note: Data for 2022 run through September.

Source: Author’s analysis based on data from Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

There are well-documented reasons that many workers are unauthorized, including impenetrable bureaucracy and corruption. As a result, many migrants seek the more secure status of a residence permit (either temporary or permanent) or citizenship, both of which allow them to work legally. Citizenship in these cases is not necessarily a marker of identity or integration but rather an instrumental tool for economic access.

Russia allows Central Asian nationals to retain their previous citizenship, but not all origin countries reciprocate dual citizenship. Indeed, when Putin announced the mobilization of additional troops in September 2022, many Central Asian countries warned their citizens abroad—including dual nationals—that serving in a foreign military conflict was illegal. This situation reinforced the decreasing value of Russian citizenship for migrants.

Between Law and Practice

Russia’s immigration system is volatile and reactive. Laws change frequently, impacting migrants’ abilities to gain and maintain legal status. At times, these changes may ostensibly allow more migrants to access legal status, but only by making the process more bureaucratic and difficult to navigate in practice. For instance, 2022 started with a new requirement for all foreign nationals to undergo invasive medical checks every three months, but the procedures were rolled back after a month of chaotic implementation and were continually adjusted throughout the year. These restrictive requirements seem contrary to subsequent changes creating simplified naturalization procedures for Ukrainians and those serving in the military. Moreover, at the end of 2022, the Ministry of Internal Affairs announced changes, to occur by 2024, to reduce consequences for migrants with minor offenses such as traffic violations. While 2022 was an unprecedented year in many ways, these contradictory immigration policies were par for the course.

In a legally volatile environment such as this, immigration enforcement policy has become crucially important. In Russia, enforcement is not uniform. Authorities often operate from a quota-driven mentality in which they aim to meet monthly targets for raids, arrests, and deportations, which does not create predictability. Some immigrants caught up in these campaigns may be criminals, but others may be pressured to confess to crimes they did not commit. In the last year, this pressure may have forced some migrants to choose between deportation and military service.

Since 2013, there has been an increasing focus on deportation, which had previously been rare. As of this writing, committing two or more administrative offenses in a year—including traffic violations—can result in expulsion and a re-entry ban for between three and five years. In practice, migrants ordered deported rarely leave the country, knowing they will not be able to return. Instead, they often fade into the shadows, hoping to avoid law enforcement.

Migrants in this precarious position have developed a resilient pragmatism and myriad coping mechanisms to mitigate risk, including working within networks of their compatriots, developing legal literacy, and avoiding public transportation and other places where authorities regularly detain migrants.

Different Factors, but Key Conditions Remain Unchanged

In a context where many immigrants exist as a permanent underclass, even a major war has not changed fundamental aspects of their day-to-day realities. Migrants face new questions about the benefits of going to Russia, pressure to enlist in the military, and consequences if arrested. Yet they have continued to balance their own agency with complex demands from families, the law, and economic systems.

Communities in origin countries still need money, compelling many migrants to remain in Russia and continue to work. Amid economic crises and other shocks over the last 15 years, migration to Russia has remained resilient. Remittances, while volatile, continue an upward trajectory. Whether the current war will break these patterns, given Russia’s increasing isolation and migrants’ complicated moral tradeoffs, remains to be seen.

Sources

Awara. 2022. Foreign Workers Do Not Have to Undergo Medical Examinations Every 3 Months — Explains the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Awara, February 7, 2022. Available online.

Arystanbek, Aizada and Caress Schenk. 2022. Racializing Central Asia during the Russian-Ukrainian War: Migration Flows and Ethnic Hierarchies. PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 788, George Washington University, Washington, DC, August 2022. Available online.

Burkhardt, Fabian. 2022. Passports as Pretext: How Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Could Start. War on the Rocks, February 17, 2022. Available online.

Burtina, Elena. 2022. Проходите без очереди. The Civic Assistance Committee, May 10, 2022. Available online.

Deutsche Welle. 2021. Russia Introduces Mandatory Medical Checks for Foreigners. Deutsche Welle, December 29, 2021. Available online.

Ebel, Francesca. 2022. Mass Shooting in Belgorod Exposes Russia’s Forced Mobilization of Migrants. The Washington Post, October 29, 2022. Available online.

Eurasianet. 2022. Was Tajik Leader’s Rant at Putin Defiance or a Plea for Greater Dependence? Eurasianet, October 17, 2022. Available online.

Intermark. 2022. Russia: Changes to Medical Checkup Requirements and Rules of Visa-Free Stay. Intermark, August 4, 2022. Available online.

Khamidov, Sanjar. 2022. Трудовые мигранты как потенциальные солдаты Минобороны РФ. Voice of America, October 4, 2022. Available online.

Kloop News. 2022. Почему мигрантам стоит бежать из России прямо сейчас – Валентина Чупик. Kloop News, October 8, 2022. Available online.

Kryakvina, Xeniya. 2019. Explaining Gaps in Russia’s Migration Policy: The Case of Compatriots Resettlement Program. Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree for Master of Arts in political science and international relations, Nazarbayev University, Astana, Kazakhstan. Available online.

Kubal, Agnieszka, 2019. Immigration and Refugee Law in Russia: Socio-Legal Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Meduza. 2022. Mass Shooting at a Russian Training Ground. Meduza, October 16, 2022. Available online.

Moscow Times. 2022. Moscow to Open Military Recruitment Center for Foreigners. The Moscow Times, September 20, 2022. Available online.

Reeves, Madeleine. 2013. Clean Fake: Authenticating Documents and Persons in Migrant Moscow. American Ethnologist 40 (3): 508-24.

Robinson, Joshua. 2022. Foreign Workers in Russia Report Invasive Examinations Under New Health Check Law. The Moscow Times, February 18, 2022. Available online.

Russia Monitor. 2021. What Is Behind Russia’s Passportization of Donbas. Russia Monitor, May 7, 2021. Available online.

Schenk, Caress. 2016. Assessing Foreign Policy Commitment through Migration Policy in Russia. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 24 (4): 475-99.

---. 2017. Labour Migration in the Eurasian Economic Union. E-International Relations, April 29, 2017. Available online.

---. 2020. Migrant Rights, Agency, and Vulnerability: Navigating Contradictions in the Eurasian Region. Nationalities Papers 48 (4): 637-43.

---. 2021. Producing State Capacity through Corruption: The Case of Immigration Control in Russia. Post-Soviet Affairs 37 (4): 303-17.

---. 2022. The Kremlin Has Another Weapon in Its Arsenal: Migration Policy. The Washington Post, April 11, 2022. Available online.

Sputnik News. 2022. В России хотят снизить число причин для включения мигрантов в черный список. Sputnik News, December 27, 2022. Available online.

Urinboyev, Rustamjon. 2020. Migration and Hybrid Political Regimes: Navigating the Legal Landscape in Russia. Oakland, Calif.: University of California Press. Available online.

Urinboyev, Rustamjon and Sherzod Eraliev. 2022. The Political Economy of Non-Western Migration Regimes: Central Asian Migrant Workers in Russia and Turkey. Berlin: Springer Nature. Available online.

Woodard, Lauren. 2019. The Politics of Return: Migration, Race, and Belonging in the Russian Far East. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree for Doctor of Philosophy, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, Mass.

Zhilin, Ivan. 2022. Сюда я больше не s. Novaya Gazeta, October 27, 2022. Available online.