You are here

Rise in Maritime Migration to the United States Is a Reminder of Chapters Past

Migrants from Haiti intercepted by U.S. authorities off the coast of Florida. (Photo: PO3 Ryan Estrada/U.S. Coast Guard)

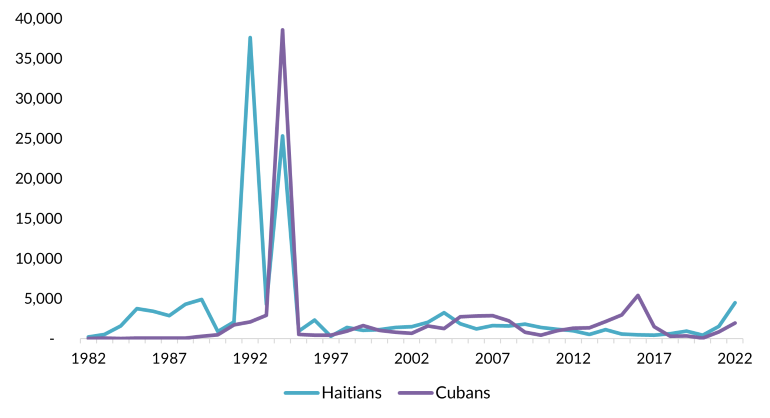

The United States is witnessing a significant increase in unauthorized maritime migration from the Caribbean, which has been largely overshadowed by rising arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico land border. While the 14,500 maritime migration attempts in fiscal year (FY) 2021 were just 1 percent of the encounters at the southwest border that year, U.S. interdictions of Haitians and Cubans at sea have collectively reached a level not seen since the 1990s. The sea arrivals can comprise a significant share for some nationalities; for example, the more than 4,400 maritime interdictions of Haitians between October and May represented nearly one-fifth of total encounters of Haitians trying to enter the United States without authorization during that period.

The spike in Caribbean interdictions has reignited a longstanding debate over the United States’ treatment of unauthorized migration at sea compared to across the land borders, and the historically disparate treatment of different groups apprehended on open waters. Attention on both sides of the political aisle has recently focused on the Biden administration’s efforts to end the Title 42 policy at the U.S.-Mexico border that results in rapid expulsions of citizens of certain countries who cross the border illegally, without access to asylum (a federal judge last week prevented the administration from lifting the policy as planned on May 23). Though Title 42 has not been applied to migrants who reach U.S. shores in South Florida or Puerto Rico, a similar practice has been in place for decades in the Caribbean: Those intercepted by the U.S. Coast Guard on the high seas have no access to the U.S. asylum system and instead are sent back to their origin countries or screened for eventual resettlement in a third country. Since this process takes place far from U.S. shores, affects fewer people, and offers little basis for legal challenges, it remains largely under the radar. And in past periods when maritime flows did receive public attention such as in the 1980s and 1990s, Cubans were often treated as exceptions to the rule, ushered into the United States while most Haitians and citizens of other countries were returned regardless of protection needs. Though this disparity has been narrowed in recent years—Cubans encountered at sea now are treated more like Haitians—the treatment is still not uniform.

This article explores the recent rise in unauthorized maritime migration through the Caribbean with echoes from prior chapters in recent U.S. history. Of course, maritime migration—both voluntary and forced—has been part of U.S. history since before the country’s founding, bringing colonial settlers and enslaved people as well as subsequent waves of European and Asian immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries. Now, most maritime migration is unauthorized, as immigrants coming from overseas through legal channels mostly travel via air. This article focuses on migration of Haitians and Cubans, given their rising numbers this year, but unauthorized migrants from other countries such as the Dominican Republic and China have also taken maritime routes. Other sea migration routes, which have been historically less used, lead from Mexico to the U.S. Pacific coast and are typically traveled by Mexicans and Central Americans.

Rapidly Rising Numbers

In the first seven months of FY 2022, the U.S. Coast Guard interdicted more Haitians at sea than during any previous full fiscal year since 1994 (see Figure 1). It interdicted nearly 2,000 Cubans at sea in the same period, more than any fiscal year since 2016 and with FY 2022 on track to be the second highest year of Cuban interdictions since 1994.

Figure 1. U.S. Coast Guard Interdictions of Cuban and Haitian Migrants, FY 1982-2022

Note: Data for Haitian interdictions for fiscal year (FY) 2022 go through May 11 and data for Cuban interdictions are through May 21.

Sources: Kathleen Newland, Elizabeth Collett, Kate Hooper, and Sarah Flamm, All at Sea: The Policy Challenges of Rescue, Interception, and Long-Term Response to Maritime Migration (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2016), available online; U.S. Coast Guard, “Coast Guard Repatriates 43 People to Cuba” (news release, May 21, 2022), available online; U.S. Coast Guard, “Coast Guard Repatriates 207 People to Haiti,” Coast Guard News, May 11, 2022, available online.

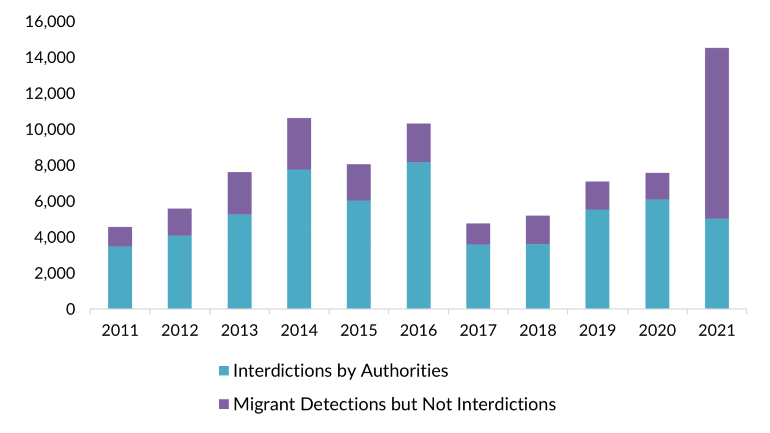

The Coast Guard does not interdict everyone it detects attempting to reach the United States without authorization. In FY 2021, the Coast Guard detected migrants attempting to enter or successfully entering the United States in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans 14,500 times, almost double the 7,600 in FY 2020, but it and other authorities (including U.S. Customs and Border Protection [CBP] and foreign navies) made only 5,000 interdictions. The share of detected migrants interdicted decreased from 77 percent in FY 2020 to 47 percent in FY 2021. When the Coast Guard receives information about migrants who successfully reach U.S. shores or it finds an abandoned migrant vessel, it counts those instances as detected noninterdictions. An unknown additional number of migrants made the maritime journey undetected.

Figure 2. Migrant Interdictions and Detections along Maritime Routes to the United States, FY 2011-21

Note: Authorities interdicting migrants include the U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and foreign navies.

Sources: Letter from Zsatique L. Ferrell, U.S. Coast Guard Freedom of Information Specialist, to Niels Frenzen, Sidney M. and Audrey M. Irmas Endowed Clinical Professor of Law and Director, Immigration Clinic, University of Southern California, June 15, 2017, available online; U.S. Coast Guard, Annual Performance Report, multiple years, available online; U.S. Coast Guard, Fiscal Year 2016 Congressional Justification (Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Guard, 2016) available online.

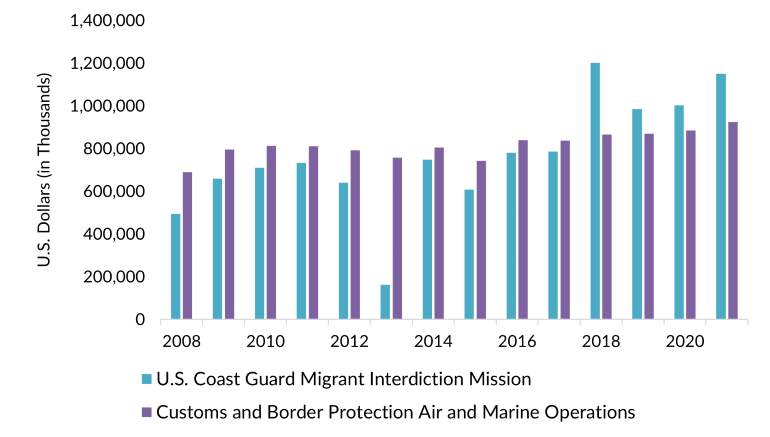

Funding Relatively Flat

Funding for U.S. maritime migration enforcement appears not to have caught up with the recent increase in flows. Congressional appropriations for the Coast Guard’s migrant interdiction mission increased 143 percent between FY 2008 and FY 2018, from $495 million to $1.2 billion, but has held steady since then; slightly less than $1.2 billion was appropriated for this mission in FY 2021. Funding for CBP’s Air and Marine Operations grew by 34 percent from FY 2008 to FY 2021, which was a slower rate than the funding increase for CBP's U.S. Border Patrol, which grew by 60 percent during this period. For FY 2023 the Biden administration requested $1.2 billion for the Coast Guard’s migrant interdiction activities and $1 billion for CBP Air and Marine Operations, similar to FY 2021.

Figure 3. Congressional Appropriations for U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection Maritime Migrant Interdiction Activities, FY 2008-21

Sources: U.S. Coast Guard, Budget in Brief, multiple years, available online; CBP, Budget in Brief, multiple years, available online.

Reasons for Increased Migration

The increase in maritime migration is principally due to deteriorating conditions in countries of origin and the absence of legal opportunities to enter the United States.

Confluence of Push Factors in Haiti

Compounding factors including gang violence, natural disasters, weak governance, and economic collapse have led Haitians to search for safety and better opportunities elsewhere. The July 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse exacerbated already dire security and political crises. Since then, gangs have been operating with increased impunity and kidnappings have risen to levels not seen since the aftermath of a 2004 coup, as gangs search for other revenue sources to make up for the absence of payments they reportedly received from the prior government. Within the country, the rise in violence and kidnappings has displaced tens of thousands of people.

Gangs have also interfered with government efforts to supply fuel nationwide and nongovernmental organizations to provide aid to people affected by the August 2021 earthquake and tropical storm. These natural disasters displaced nearly 40,000 people and damaged or destroyed more than 100,000 homes.

Further, the country has experienced a yearslong political crisis. At the time of the assassination, Moïse's legitimacy to hold office was disputed, and he had recently removed three Supreme Court justices. Prime Minister Ariel Henry, the current leader, survived an assassination attempt in January and leads a government that some view as unconstitutional. The government is thus poorly equipped to serve the population, 43 percent of which may need humanitarian assistance according to the United Nations; 4.5 million face acute food insecurity.

Economic Crisis and Government Repression in Cuba

Pressures driving migration from Cuba have also increased in recent years. The country is undergoing its worst economic crisis since after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. COVID-19 has deepened the distress, particularly for the tourism industry. But the economy was struggling even before the pandemic, especially under the weight of sanctions imposed by the Trump administration that included restrictions on U.S. travel and remittances to the island, as well as diminishing aid from Venezuela. Currency reforms and pandemic-related shortages caused inflation to spike, with overall prices rising 70 percent in 2021.

Further, government repression increased after widespread protests broke out in July 2021—themselves an extremely rare event in Cuba, demonstrating the extent of the public’s frustration. Mass detentions and prosecutions followed the protests, likely causing more people to flee either because they feared arrest or had lost any hope for change.

Limited Legal Pathways

Both Haitians and Cubans have few easy legal ways to migrate to the United States, resulting in attempts to travel irregularly. According to the Henley Passport Index, which measures access to visa-free travel, Haitian passport holders require a visa to visit more countries than nationals of any other country in the Western Hemisphere. Haitians face significant obstacles to securing a U.S. visa, including costly and potentially dangerous travel to an embassy or consulate, high denial rates for those looking to come as tourists, and fees plus the cost of a plane ticket. Further, COVID-19 has slowed U.S. visa issuance worldwide.

Cuban passports are the second-most restricted in the Western Hemisphere in terms of visa-free travel. Cubans have historically had special legal pathways to the United States, but most of these pathways have been blocked since 2017. Since 1995, the United States has committed to admitting 20,000 Cubans annually through various pathways, including immigrant visas and parole. However, almost all visa and parole processing stopped when the Trump administration removed most staff from the U.S. embassy in Havana in 2017 due to mysterious illnesses among diplomats. Cubans were instead directed to travel 1,500 miles to Guyana for their visa interviews, which many could not afford. The U.S. embassy in Havana resumed limited visa processing in May, but most applicants were still being processed abroad. It also announced it would soon resume parole processing.

Use of Maritime Routes when Land Crossings Are Not an Option

Despite the increasing numbers trying to reach the United States by sea, many more Haitians and Cubans have been arriving at the southwest border. But there are multiple differences between those who attempt sea crossings and those who come by land, often via Central America. For one, most Haitians arriving at the U.S. land border have come there after previously migrating to South American countries in the aftermath of Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, followed by years of deteriorating economic conditions. In those years, countries such as Brazil and Chile had more welcoming visa policies for Haitians, partly driven by labor market needs, including in the lead up to the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics in Brazil. As jobs dried up upon completion of these projects, many attempted to go elsewhere, including to the United States. The economic fallout from COVID-19, increasingly restrictive South American immigration policies, and experiences of discrimination drove further migration to the U.S. border. The 2010 earthquake also resulted in many Haitians being eligible for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in the United States, which increased the number who settled and thereby created further incentive for family reunification there. For those still in Haiti, entering the United States by land was difficult, prompting many instead to take maritime crossings.

Additionally, since March 2020, the United States has expelled 19,000 Haitians from the U.S.-Mexico border to Haiti, a country in which many have not lived for years. In an early 2022 survey by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), 84 percent of expelled Haitian migrants said they intended to migrate again in the future. While many have left for South American countries, some may be turning to the maritime route towards the United States.

Cubans, however, have benefited from looser visa requirements to enter Nicaragua, which has provided them a possible land route to the United States. In 2018, Nicaragua reduced requirements for Cubans to obtain a tourist visa, and in November 2021 it eliminated them altogether. Many Cubans have since been able to fly to Nicaragua and then move north by land; people who have taken the maritime route may be those who could not afford a flight.

Box 1. Maritime Migration from the Dominican Republic and China

Aside from Haitians and Cubans, citizens of a handful of other countries have attempted to reach U.S. shores in increasing numbers over particular periods.

Dominican Republic

Irregular maritime migration from the Dominican Republic emerged in the second half of the 20th century. It has peaked several times, including in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. Dominicans typically aim for Puerto Rico, 80 miles to the east, and in earlier decades migrants often used the U.S. territory as a steppingstone, sometimes procuring a false Puerto Rican identity document upon arrival and then taking a flight to the mainland United States, a trip that did not require a visa or passport. As U.S. airport security increased, Dominicans became more likely to stay in Puerto Rico. The peak year for U.S. Coast Guard interdictions of Dominicans was fiscal year (FY) 1996, when more than 6,000 were apprehended.

China

The number of Chinese migrants arriving via sea without authorization spiked in the 1990s, with a high of 2,500 interdicted by the Coast Guard in FY 1993. Such trips were organized by smugglers, often originated in the Fujian province of China, and traversed routes to both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States. The most infamous of these journeys occurred in 1993, when the Golden Venture, a ship holding nearly 300 unauthorized Chinese migrants, ran aground off a New York City beach. This incident drew significant publicity, catalyzed smuggling crackdowns by both the Chinese and U.S. governments, and led to a U.S. policy of attempting to interdict ships smuggling migrants as far from shore as possible. It is now more common for Chinese citizens to fly to Mexico and subsequently cross the U.S. land border without authorization.

Sources: Jorge Duany, “Dominican Migration to Puerto Rico: A Transnational Perspective,” Centro Journal, 17, no. 1 (2005): 242-69, available online; David Scott FitzGerald, Refuge beyond Reach: How Rich Democracies Repel Asylum Seekers (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); Kathleen Newland, Elizabeth Collett, Kate Hooper, and Sarah Flamm, All at Sea: The Policy Challenges of Rescue, Interception, and Long-Term Response to Maritime Migration (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2016), available online; Jon Nordheimer, “Puerto Rico Seen as Backdoor Pipeline for Aliens Fleeing Dominican Republic,” The New York Times, December 17, 1986, available online; Jennifer Riddle, “The Golden Venture and American Immigration Laws,” Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies 17, no. 2 (1999): 2-14, available online; Joseph B. Treaster, “U.S. Plans Tougher Strategy to Combat Alien Smuggling,” The New York Times, June 14, 1993, available online.

History of Caribbean Maritime Migration

Recent irregular maritime migrants are following a path that has been traveled for decades. Significant unauthorized maritime migration from Cuba and Haiti emerged in the second half of the 20th century, though some number of Caribbean migrants came to the United States earlier, mostly via legal pathways. Citizens of Western Hemisphere countries were not limited by the restrictive quota system in place from the 1920s through 1965, but increased opportunities for family-based immigration in the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act contributed to a rise in migration from across the Americas, including the Caribbean. Expanding family networks in the United States incentivized further immigration.

1960s and 1970s: Maritime Route Emerges

Shortly following the 1959 Cuban Revolution, a handful of boats made the journey to South Florida, and those numbers increased after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis led to a cutoff of commercial travel to the United States. In 1965, in a precursor to future mass Cuban migration events, the Cuban government opened the port of Camarioca, allowing several thousand Cubans to leave. In response, to avoid prolonged mass irregular migration, the U.S. government ran twice-daily flights from Varadero, Cuba, to Miami for the next eight years. Additionally, the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act allowed Cubans admitted or paroled into the United States to apply for permanent resident status after just one year, setting the stage for 50 years of special treatment of Cuban migrants.

Unlike policies for Cubans, U.S. treatment of Haitian migrants has largely focused on repatriation, starting in the 1970s. During that decade, Haitian maritime migration rose gradually because of economic hardship and political repression under the dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier. Between 1972 and 1979, a small number of Haitian migrants reached the shores of Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, encountering U.S. officials at the naval base there. The U.S. government flew the first group to the U.S. mainland and aided some subsequent groups with ship repairs, allowing them to continue their journeys, while those with excessively damaged ships were held at the base and given asylum interviews. However, U.S. officials ultimately sent most back to Haiti. Notably, this was the start of Guantanamo Bay’s use as a migrant detention center, which continues to this day.

1980s: Cuban Mass Migration and Restrictions on U.S. Protection for Haitians

Maritime migration accelerated in the 1980s. In 1980, about 125,000 Cubans arrived in Miami after President Fidel Castro allowed U.S. vessels to enter the Mariel port to pick up relatives of U.S. immigrants, but also required them to take people the Cuban government saw as undesirable, in what became known as the Mariel boatlift. This incident marked the beginning of the end of the United States’ generally welcoming posture toward Cuban migrants. Cuban maritime emigration slowed for the rest of the decade as the Cuban government reimposed strict exit controls.

Haitian immigration also increased in 1980, with as many as 18,000 migrants entering without authorization. In response, the United States and Haiti signed a 1981 agreement allowing the Coast Guard to board Haitian vessels that U.S. authorities believed were carrying unauthorized migrants and return them to Haiti. Concurrently, President Ronald Reagan signed an executive order officially adding migrant interdiction to the Coast Guard’s responsibilities. Intercepted Haitians were afforded asylum screening interviews; those who did not pass were returned to Haiti while those who did were taken to the United States to continue their claim. Access to asylum, however, existed more in theory than in practice: from 1981 to 1989, U.S. authorities interdicted 21,500 Haitians, but only six were brought to the United States to pursue asylum claims.

1990s: Skyrocketing Maritime Migration and Restriction of Access to Protection

Maritime migration exploded in the 1990s, resulting in U.S. restrictions for both Haitians and Cubans. However, Cubans continued to have more opportunities for U.S. protection.

A 1991 coup overthrowing Haiti’s democratically elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide and subsequent violence led to another surge in Haitian migration. While the United States initially suspended interdictions as a show of support to Aristide and the Haitian people, this was a short-lived interlude and enforcement resumed within two and a half weeks. With many more Haitians taking to the sea and the Coast Guard lacking sufficient resources to screen them for protection onboard ships, the United States turned to conducting asylum screenings at Guantanamo Bay. In the six months following the coup, 10,500 Haitians were paroled into the United States to pursue asylum claims, while 550 were resettled in Central American and Caribbean countries. However, Guantanamo reached capacity in May 1992.

That month President George H.W. Bush directed authorities to return Haitians without providing asylum screenings, unless the attorney general instructed otherwise, eliminating any pretense of providing protection. The Supreme Court in 1993 upheld this policy, ruling that interdictions in international waters were not subject to U.S. humanitarian protection laws. The administration announced that Haitians could apply for asylum from within their country, though approvals were incredibly rare. The interdiction policy was in place until the following year, when the Clinton administration briefly resumed asylum screenings on a U.S. Navy ship off the coast of Jamaica. However, this effort was quickly overwhelmed and Haitians were again sent to Guantanamo for screenings; most were repatriated when Aristide returned to office later that year.

Restrictive policies were also enacted for Cubans. In late summer and early fall of 1994, in what came to be called the balsero (“rafter”) crisis, Castro lifted exit controls, and approximately 31,000 Cubans were interdicted at sea. The Clinton administration, fearing another Mariel boatlift, sent them to U.S. bases at Guantanamo Bay and in Panama; however, most were eventually paroled into the United States. In 1994 and 1995, the United States and Cuba agreed to stem irregular migration, effectively closing off access to the United States for migrants caught at sea. While Cuba agreed to try to prevent unauthorized maritime departures, the United States agreed to admit at least 20,000 Cubans annually. The United States also established the “wet foot, dry foot” policy, under which Cubans interdicted at sea would be repatriated unless they stated a fear of persecution, in which case they would be considered for third-country resettlement, while Cubans who reached U.S. land would continue to have a fast track to permanent residence.

Despite Changing Circumstances, Policy Has Hardly Evolved for Nearly Three Decades

Most of the policies implemented in the 1990s remain in effect, giving the current moment a sense of déjà vu. Migrants of any nationality intercepted at sea have no route to come to the United States; they are either repatriated or held at Guantanamo Bay while the United States looks to resettle them in another country. They are not always given asylum screenings: Amid increased Haitian maritime migration in 2004, following a second coup against Aristide, the Coast Guard did not provide credible fear interviews unless Haitians affirmatively sought them—in contrast to Cubans, who were asked if they feared returning to Cuba. Haitians who made it to U.S. soil would typically be detained and processed for removal.

One key change is that in 2017 the Obama administration ended the wet foot, dry foot policy as part of its rapprochement with Cuba. Cubans who reach U.S. soil may still request asylum, just like migrants of other nationalities (except those who since 2020 have been immediately expelled under the Title 42 policy), but they are much more likely to win their claims than Haitians. Thus, even though U.S. policy now applies similar restrictions to Cubans and Haitians, disparities still exist.

Dynamics may be on the verge of changing. The Biden administration announced in May that it would lift some sanctions on Cuba—including restrictions on flights, group educational travel, and remittances—which could relieve some pressure on the Cuban economy. The administration also announced that it would restore the Cuban Family Reunification Parole Program, which allows for temporary parole within the United States of people applying to become lawful permanent residents (also known as green-card holders) through family members who already hold a green card. The reopening of parole and increased visa processing at the U.S. embassy may redirect potential migrants from irregular routes—whether at the border or on the high seas—to legal channels.

Sources

Bush, George H.W. 1992. Executive Order 12807—Interdiction of Illegal Aliens. The American Presidency Project. Available online.

Centre d’analyse et de recherche en droits de l’homme (CARDH). 2022. Kidnapping: Bulletin #7. Bourdon, Haiti: CARDH. Available online.

Dalby, Chris. 2022. Haiti's Kidnapping Crisis Grows Ever More Desperate in 2022. InSight Crime, April 11, 2022. Available online.

Duany, Jorge. 2017. Cuban Migration: A Postrevolution Exodus Ebbs and Flows. Migration Information Source, July 6, 2017. Available online.

FitzGerald, David Scott. 2019. Refuge beyond Reach: How Rich Democracies Repel Asylum Seekers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Held, Douwe Den and Chris Dalby. 2021. Truce or No Truce: Gangs in Haiti Control Aid Movement. InSight Crime, August 31, 2021. Available online.

Kahn, Jeffrey S. 2021. Guantánamo’s Other History. Boston Review, October 15, 2021. Available online.

Kurmanaev, Anatoly and Oscar Lopez. 2022. Mass Trials in Cuba Deepen Its Harshest Crackdown in Decades. The New York Times, January 14, 2022. Available online.

Newland, Kathleen, Elizabeth Collett, Kate Hooper, and Sarah Flamm. 2016. All at Sea: The Policy Challenges of Rescue, Interception, and Long-Term Response to Maritime Migration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Palmer, Gary W. 1998. Guarding the Coast: Alien Migrant Interdiction Operations at Sea. International Law Studies 72: 157-79. Available online.

Psaledakis, Daphne, Matt Spetalnick, and Humeyra Pamuk. 2022. U.S. Revises Cuba Policy, Eases Restrictions on Remittances, Travel. Reuters, May 16, 2022. Available online.

ReliefWeb. N.d. Haiti: Earthquake - Aug 2021. Accessed May 21, 2022. Available online.

Rodríguez, Andrea. 2022. Shortages, Inflation Frustrate Cubans Struggling to Get By. Associated Press, February 17, 2022. Available online.

Saffon, Sergio. 2021. 3 Reasons Why Kidnappings are Rising in Haiti. InSight Crime, October 22, 2021. Available online.

Tennis, Katherine H. 2021. Offshoring the Border: The 1981 United States–Haiti Agreement and the Origins of Extraterritorial Maritime Interdiction. Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1): 173-203.

Thomas, Gessika. 2022. Haitian Prime Minister Survives Weekend Assassination Attempt--PM’s Office. Reuters, January 3, 2022. Available online.

Thomas, Kevin J. A. 2012. A Demographic Profile of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

UN News. 2022. Haiti: UN Agencies Warn of ‘Unabated’ Rise in Hunger. UN News, March 22, 2022. Available online.

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 2022. Latin America & the Caribbean Weekly Situation Update (7-13 March 2022). UN OCHA, March 14, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Coast Guard. 2020. Maritime Law Enforcement Assessment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Available online.

U.S. Coast Guard, Office of Program Analysis and Evaluation. 2021. U.S. Coast Guard: FY2021 Performance Report. October 8, 2021. Available online.

Wasem, Ruth Ellen. 2011. U.S. Immigration Policy on Haitian Migrants. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.