New Era in Immigration Enforcement at the U.S. Southwest Border

Border Patrol Riverine Unit rescues a stranded child on the banks of the Rio Grande River. (Photo: CBP/Donna Burton)

This year marked a transition to a new chapter in the United States’ three decade-long effort to limit illegal immigration across the Southwest border. Previously, border crossers were primarily Mexican men pursuing employment, with most attempting entry in Arizona and California. The flow has increasingly shifted to Southeast Texas and from predominantly Mexican to majority Central American since 2012, with a rising share of children and families included in the stream. That trend was sharply underscored in the late spring and summer of 2014, with the surge in arrivals of unaccompanied children and parents with young children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. (For more on the flows, see Issue #3: Border Controls under Challenge: A New Chapter Opens.)

The Four Phases of Modern Southwest Border Enforcement

These recent changes have ushered in a fourth distinct period in the modern history of Southwest border enforcement. The first began in the 1980s, when growing concern over illegal immigration contributed to the passage of two major laws: the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) and the Immigration Act of 1990, which both authorized sizeable resource increases for the U.S. Border Patrol, the agency in charge of enforcement between ports of entry. Nonetheless, apprehensions of unauthorized immigrants at the Southwest border—a proxy measure of illegal border crossers—averaged 1.1 million per year in the decade after IRCA’s passage.

|

Issue No. 5 of Top Ten of 2014 |

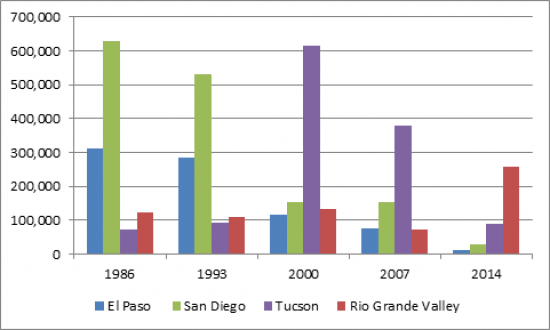

Implementation of the Border Patrol’s first National Border Patrol Strategy initiated the second period of border enforcement in 1994. Earlier enforcement had been mainly undertaken at some distance from the border, and most decisions about deploying Border Patrol resources were made at the local or sector level. The 1994 strategy called for surging personnel and infrastructure along the immediate border line, with a focus on the areas with the largest numbers of apprehensions, beginning with the border’s two biggest metropolitan areas: El Paso and San Diego. While the total volume of apprehensions was unchanged over the next decade, apprehensions fell in the El Paso Sector by two-thirds and in the San Diego Sector by 80 percent.

The enforcement surge in San Diego and El Paso displaced border crossers to more rural and remote areas, primarily in the Tucson Sector, where apprehensions peaked at 616,000 in 2000. That year also marked the high point for border-wide apprehensions (1.64 million), and the start of the third phase, lasting until 2011, of the Border Patrol’s modern efforts. These years saw unprecedented investments in border enforcement, particularly in the Tucson Sector, as Border Patrol staffing along the border more than doubled (from 9,212 to 21,444 agents), and staffing in Tucson almost tripled (from 1,548 to 4,239 agents). U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) also installed 577 miles of new border fencing (adding to 72 existing miles), covering all but a few miles of the 370-mile Arizona border. This robust enforcement—along with the country’s slow recovery from the Great Recession, Mexico’s relatively strong economic performance and its declining birth rate since the 1980s—produced a sustained drop in apprehensions, which fell to 328,000 border-wide in 2011, one-fifth the number recorded in 2000. (For more on Mexico and its migration role, see Issue #8 Changing Landscape Prompts Mexico’s Emergence as a Migration Manager.)

A New Reality: Changing Geographies and Demographics

The current fourth phase of Southwest border control, beginning in 2012, is fundamentally different from the earlier three. Apprehensions are flat or falling in eight out of nine Southwest border sectors, but surging in Rio Grande Valley (RGV), the easternmost sector. The drop in apprehensions is most notable in the Tucson Sector, which recorded an 86 percent decline from 2000 to 2014, with 88,000 in 2014. Meanwhile, apprehensions in RGV climbed from 60,000 in 2011 to 256,000 in 2014—a 326 percent increase in just three years. The RGV Sector accounted for 53 percent of border-wide apprehensions (256,000 out of 479,000) in 2014, the highest proportion ever recorded in a single sector.

|

Figure 1. Border Apprehensions, by Sector, Selected Years

|

|

Source: For all years but 2014, U.S. Border Patrol, "Southwest Border Sectors, Total Illegal Apprehensions by Fiscal Year," www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/U.S.%20Border%20Patrol%20Fiscal%20Year%20Apprehension%20Statistics%201960-2013.pdf; for 2014, U.S. Border Patrol, "Sector Profile - Fiscal Year 2014," http://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/USBP%20Stats%20FY2014%20sector%20profile.pdf. |

Even these numbers fail to capture how much has changed along the border. In 2014, for the first time, non-Mexicans (overwhelmingly from the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) accounted for a majority (53 percent) of people apprehended at the Southwest border. Non-Mexicans accounted for 75 percent (193,000 out of 256,000) of those apprehended in the RGV Sector. By comparison, non-Mexicans accounted for just 6 percent of Southwest border apprehensions between 2000 and 2009. Perhaps most strikingly, unaccompanied children and family units comprised primarily of women and children accounted for 29 percent (137,000) of Southwest border apprehensions in 2014, up from 13 percent in 2013.

These changes were driven by a recent acceleration in child and family migration from the Northern Triangle. Emigration of children and families stems from a complex mix of factors, including pervasive violence, poor economic opportunities, and the presence in the United States of family members ineligible to sponsor them for lawful immigration as a result of their own lack of full legal status. While Mexican border crossers in earlier periods were overwhelmingly deportable under U.S. immigration law, recent Central American arrivals present a classic “mixed flow:” many are deportable, but a large number (mostly women and children) have valid asylum or other humanitarian claims.

Implications for U.S. Border Policy and Enforcement Strategies

This new migration pattern has important implications for U.S. border policy. First, the shifting geography of illegal immigration requires a nimble response from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). The lack of sufficient resources to process arriving children and families in the RGV Sector in 2014 created a significant policy challenge—and a major political one for the Obama administration. DHS’s new southern border strategy, announced as part of President Obama’s immigration executive actions in November 2014, may give DHS greater flexibility in managing border resources. (For more on the executive action, see Issue #2: President Obama Breaks Immigration Impasse with Sweeping Executive Action.)

Second, the high volume of mixed flows highlights the need for faster and fairer immigration hearings. Given the dangerous conditions in Central America, many arriving immigrants have an opportunity to plead their case for humanitarian relief before an immigration judge, meaning the United States should not employ fast-track deportation proceedings in these cases. But long backlogs in immigration courts leave apprehended women and children in limbo for years—ineligible for immigration benefits, but not yet subject to deportation. The delays also encourage additional illegal migration by sending a message that child and family arrivals from Central America will not be deported, at least not for a period of months or years.

Third, changes in the demographics and motivations of border crossers challenge core elements of U.S. border control strategy. The Border Patrol deters repeat crossers by imposing burdensome consequences during the deportation process, including expedited removal, repatriation through remote ports of entry, and criminal charges that carry prison time. These consequences were designed to deter Mexican men, but women and children generally have the right to a hearing and cannot be given prison time for illegal re-entry. Deporting Central Americans is also complex because they must be flown to their home countries—a more expensive and logistically difficult proposition than deporting Mexicans at land ports of entry. These challenges raise the question of what consequences might deter unauthorized Central Americans while still meeting the responsibility under U.S. and international law to protect vulnerable migrants. More fundamentally, U.S. border control strategies seek to deter border crossers through the threat of enforcement, but people fleeing desperate conditions may not be easily discouraged, particularly if their lives are at stake.

Features

- Dramatic Surge in the Arrival of Unaccompanied Children Has Deep Roots and No Simple Solutions

- Unaccompanied Minors Crisis Has Receded from Headlines But Major Issues Remain

- Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States

- Immigration in the United States: New Economic, Social, Political Landscapes with Legislative Reform on the Horizon

- Immigration Enforcement in the United States

- From Horseback to High-Tech: U.S. Border Enforcement

MPI Research

- Deportation and Discretion: Reviewing the Record and Options for Change

- The Deportation Dilemma: Reconciling Tough and Humane Enforcement

- What Is the Right Policy Toward Unaccompanied Children at U.S. Borders?

- Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery

- U.S. Immigration Policy and Mexican/Central American Migration Flows: Then and Now

- Obstacles and Opportunities for Regional Cooperation: The U.S.-Mexico Case

Sources

U.S. Border Patrol. N.d. Southwest Border Sectors, Total Illegal Apprehensions by Fiscal Year. Available Online.

---. N.d. Sector Profile - Fiscal Year 2014. Available Online.