You are here

Crisis Prompts Record Emigration from Nicaragua, Surpassing Cold War Era

Crossers at the Nicaragua-Costa Rica border. (Photo: World Bank)

Haga clic aquí para leer este artículo en español.

When Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega returned to power in 2007 after 17 years in the opposition, his first two five-year terms oversaw robust economic growth and a decrease in poverty. Even the World Bank, long a critic of Ortega’s leftist policies, lauded the country’s development, noting its market-oriented reforms and sound macroeconomic management. But Ortega’s authoritarianism grew, as he and his Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) abolished presidential term limits, cracked down on dissidents, and, in 2017, elevated his wife, Rosario Murillo, to the vice presidency. The erosion of democracy and violence against protestors sparked what has become the largest emigration in the country’s modern history, surpassing that of the Cold War era.

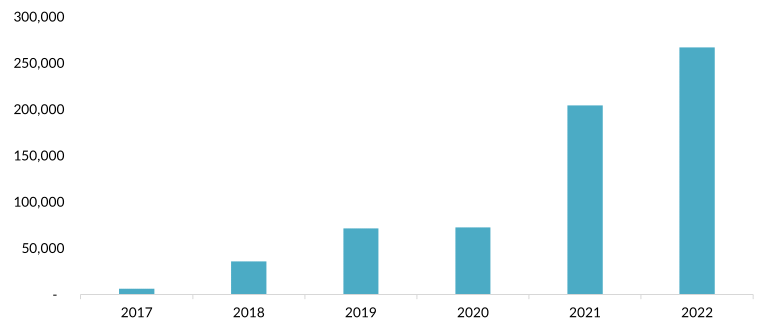

As of 2020, more than 100,000 Nicaraguans had fled the country, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). By 2022, that number approximately doubled, as Ortega cracked down on opposition politicians and political dissidents in the run up to and following November 2021 elections widely viewed as rigged.

Mostly, emigrants have gone to neighboring Costa Rica, a popular destination due to its proximity and economic and political stability. Sometimes referred to as the Switzerland of Central America, Costa Rica has historically attracted Nicaraguan immigrants, typically low-wage workers with little education. But as this migration pattern has expanded in recent years, the demographics of migrants have changed; many asylum seekers and other Nicaraguans now in Costa Rica are better educated, among them some opposition activists. The influx, meanwhile, has overwhelmed Costa Rica’s asylum system and at times prompted protests from Costa Ricans. In late 2022, the Costa Rican government imposed new restrictions for asylum seekers, who President Rodrigo Chaves said often “abused” the system.

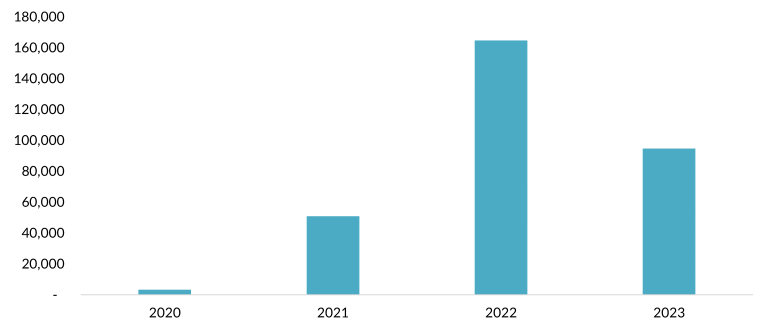

Partly as a result, many have looked toward the north, including the United States. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) encountered unauthorized Nicaraguan migrants nearly 165,000 times in fiscal year (FY) 2022, a 52-fold increase over FY 2020. Numbers increased to a monthly record high of nearly 35,500 in December, before dropping in January when the Biden administration enacted new restrictions expelling Nicaraguans arriving without authorization, while allowing some with a U.S. sponsor to enter the country on parole.

This exodus has seriously affected countries across the Americas, which are reckoning with large numbers of Nicaraguan migrants as they seek to recover from economic and other impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. For Nicaragua, which has a population of less than 7 million, the flight has proven to be a serious brain drain, depriving the country not only of political leaders but also all manner of intellectuals, artists, and academics. Its deepening political crisis has hit all walks of life, and those with the ability to flee have been among the quickest to depart.

This article provides an overview of the rapid emigration from Nicaragua since mid-2018 and puts it in historical context.

Figure 1. Map of Nicaragua

The 2018 Political Crisis

The current crisis can be traced most directly to April 18, 2018, when the Ortega government cut monthly social security pensions for the elderly by 5 percent and increased taxes for employees and employers. The policies, which were supported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, were grossly unpopular at home. Nicaragua is among the poorest countries in the Western hemisphere; a decrease in the monthly retirement pension and tax increases would have likely pushed many families deeper into poverty.

In response, protests mushroomed across the country. Nicaraguans of all political leanings took to the streets, giving birth to the Movement of April 19 (Movimiento de 19 de abril). The government’s response was swift: Dissent was met with violence and opposition figures were imprisoned. By that August, more than 300 protesters had been killed and thousands had been wounded. Prisons swelled with political prisoners. Although the government rescinded the law, it failed to quell the opposition. National strikes and protests increased.

Ortega and his government were condemned by 14 Latin American countries. For many, Ortega was no longer a revolutionary hero who had helped overthrow dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle, but instead an aging autocrat embracing violence to clumsily ensure his grip on power.

This dynamic became clear as the weeks and months progressed. At the March of the Flowers (la Marcha de las Flores), one of the largest protests in 2018, Ortega allies injured and killed multiple protesters. In academic literature, these paramilitary groups are often referred to as violent specialists: loosely affiliated individuals outside of the formal military or police who commit acts of terror to support specific leaders and movements.

To be sure, the opposition movement also carried out acts of political violence. Anti-government forces burned down the New Radio Ya, an Ortega-friendly media outlet, while also attacking university and government offices and harassing Ortega supporters. A number of police officers were kidnapped and killed. Two Ortega supporters were burned in the streets while onlookers applauded. The area of the University of Central America, once a bustling urban center, resembled a war zone.

That June, an umbrella group of opposition movements known as the Nicaraguan Civic Alliance for Justice and Democracy organized a national strike. Protestors installed barricades (tranques) around Managua, Nicaragua’s capital and most populated city, cutting off exits and entrances into town.

Protesters even took over Masaya, a Sandinista stronghold southeast of Managua. Ortega’s support proved vital in reclaiming the main police precinct there, after protesters had barricaded themselves for more than two weeks. This military success, led by former guerrilla and experienced military tactician General Glauco Robelo, who had proved integral in the 1979 offensive against Somoza, was a major win for the government.

Who Is on Which Side?

Although Ortega supporters such as Robelo are Sandinista, the broad-based movement and political party that overthrew Somoza, the current dynamic is more complex than a Sandinista government versus an anti-Sandinista opposition. Much of the opposition has come from dissident Sandinistas who have fought Ortega’s stranglehold on the party.

The legendary guerrilla Dora María Téllez, for example, who oversaw the successful Operation Chanchera that took over the Somocista National Congress in 1978, has become a key player against Ortega. Imprisoned by the government in June 2021, she was found guilty of political conspiracy in 2022. Other prominent figures include Ana Margarita Vijil, a lawyer and human-rights activist, and Lester Alemán, a university student who became famous for calling Ortega an “assassin.” Alemán was convicted alongside Téllez in 2022.

Many lesser known and younger government opponents identify with Ortega’s party even as they rebel against him. One man interviewed by the author in Nicaragua in 2018 identified himself as “100 percent” Sandinista yet harbored such hatred for the president that he hoped someone would kill him.

What Is Driving Migration?

With such a broad-based opposition movement, the country was teetering on the verge of collapse. Businesses shuttered and gross domestic product (GDP) decreased sharply. The loss of work affected every corner of Nicaragua, from the working class to the elite. And while the government insisted its efforts to battle the COVID-19 virus have been successful, independent analysts have accused it of hiding the disease’s true toll.

A renewed government crackdown ahead of 2021 presidential elections was far more impactful in driving emigration. The election, which ushered in Ortega’s fourth consecutive win (his fifth overall) and guaranteed his party a supermajority in the National Assembly, was denounced as a sham by the European Union, the United States, and other governments. Ahead of the vote, major opposition candidates were imprisoned.

In response, the United States and European Union imposed sanctions against Ortega and his inner circle. Meanwhile, the economic fallout from the pandemic pushed the country into its third consecutive year of recession in 2020, although the economy subsequently rebounded.

Figure 2. Humanitarian Migrants from Nicaragua, 2017-22*

* Data for 2022 run through the middle of the year.

Note: Figure includes Nicaraguan refugees, asylum seekers, and others identified by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to be of concern.

Source: UNHCR, “Refugee Data Finder,” accessed March 3, 2023, available online.

A Swelling Population of Asylum Seekers in Costa Rica

Following age-old migration patterns, the bulk of Nicaraguans have gone to neighboring Costa Rica, which is experiencing a record level of humanitarian migration. Nicaraguans sought asylum in Costa Rica just 67 times in 2017, but numbers increased dramatically to 23,000 in 2018 and continued to rise precipitously. As of June 2022, Costa Rica hosted 205,000 asylum seekers—89 percent of them from Nicaragua—in addition to 11,000 refugees. Despite Costa Rica’s modest population, the country received the fourth largest number of asylum applications globally in 2021, behind only the United States, Germany, and Mexico, according to UNHCR.

The influx has strained Costa Rica’s systems, leading to lengthy processing backlogs and making it difficult for many applicants to access formal asylum. Some Costa Rican officials have suspected many Nicaraguans are seeking economic opportunities and would not be truly at risk of harm in their native country. In 2022, Chaves’s government enacted some restrictions on the country’s famously welcoming policy, requiring new applicants to register their case within a month of arrival and enroll in the social security system, and removing the promise of an expedited work permit. Migrants from Nicaragua (along with Cubans and Venezuelans) who offered to drop their asylum case also became eligible for temporary work permits, which may have prompted many to opt out of the asylum system.

Destination Panama and North America

Partly as result of the changing situation in Costa Rica, other countries have also begun attracting Nicaraguans. Many have gone to Panama or embarked on an often dangerous journey north, hoping to cross the U.S.-Mexico border. This has put transit and receiving countries in a delicate position—and Nicaraguans in an even more precarious one.

Take Mexico for example, where Nicaraguans have repeated sought to transit the country to reach the United States, at times in large caravans. Unlike earlier caravans of mostly Honduran migrants during Semana Santa of 2017, recent years have seen increasing numbers of Nicaraguans moving through the country.

The arrivals are not always welcomed. Mexican authorities have increasingly sought to break up groups of migrants, including memorably attacking and gassing some along the Suchiate River bordering Guatemala in early 2020. In general, Nicaraguans often say they experienced prejudice in Mexico.

Still, some Nicaraguans have decided to stay in Mexico. In the first 11 months of 2022, more than 8,700 Nicaraguans requested asylum in Mexico, a more than tenfold increase over the 800 who sought protection in 2020. Since 2013, about 65 percent of those whose cases have been decided received refugee status or another form of protection.

One Nicaraguan in Mexico is Alejandra Gonzalez, a former journalist for the Nicaraguan newspaper La Prensa, who said she feels comfortable in the country. Another is José Adiak Montoy, a successful Nicaraguan author, who told the author he lost his job at a cultural center in Managua and fled to Mexico.

Yet for many northbound Nicaraguans, the goal is the United States. But those lucky enough to land in el norte face new challenges.

Figure 3. U.S. Customs and Border Protection Encounters of Unauthorized Nicaraguan Migrants, FY 2020-23*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 cover the first four months of the fiscal year, which begins on October 1.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Nationwide Encounters,” updated February 6, 2023, available online.

Because of limited diplomatic relations between the United States and Nicaragua, U.S. authorities previously rarely rapidly expelled Nicaraguans under the pandemic-era Title 42 policy. But increasing arrivals have prompted a more restrictive approach. In early 2023, the Biden administration announced a policy allowing it to expel to Mexico monthly up to 30,000 Nicaraguans, Cubans, Haitians, and Venezuelans. The policy was paired with a new system allowing up to 30,000 nationals of these four countries to enter the United States on humanitarian parole, so long as they apply from outside the United States, have a U.S. sponsor, and meet other qualifications.

In recent years, many Nicaraguan asylum seekers have been temporarily detained in U.S. facilities and then released into the country to await immigration court proceedings. However, during the Trump administration and early Biden period, some were subjected to the now-ended Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, informally known as the Remain in Mexico program), which allowed U.S. authorities to send asylum seekers and other irregularly arriving migrants to Mexico to wait out the duration of their proceedings.

The likelihood of release into U.S. territory has been described as a lure for asylum seekers, given that lengthy immigration court backlogs mean that migrants might wait for years for their case to be resolved. As a whole, 43 percent of Nicaraguans receiving a decision on asylum through U.S. immigration courts in FY 2022 received some form of protection.

Historical Overview: Cold War-Era Migration Patterns

The current exodus from Nicaragua can be contextualized in a broader history of strongman politics and migration since the early 20th century, particularly amid U.S. intervention in Central America that brought conflict, misery, and poverty. In 1909, President William Howard Taft sent warships to Nicaragua as a sign of support for the coup against liberal dictator José Santos Zelaya, who was opposed to U.S. regional interests. Afterwards, Washington built up a military presence in the country until opposition from forces led by Nicaraguan nationalist Augusto Sandino prompted a U.S. withdrawal. Shortly thereafter, the U.S.-supported head of the Nicaraguan National Guard, General Anastasio Somoza García, ordered the assassination of Sandino and oversaw a coup installing himself in power. The Somoza dynasty ruthlessly governed the country for the next four decades.

As resistance grew against the Somozas’ dictatorship, so did war and suffering. When Somoza’s son, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, was deposed by Sandinistas in 1979, his ouster was accompanied by a wave of migration to the United States and, to a lesser extent, Costa Rica. Many of these migrants were individuals who had been associated with the Somoza government, including an economic and military elite.

Second and third waves of emigration began in 1982 and 1985, as President Ronald Reagan increased U.S. support for anti-Sandinista rebels known as the Contra. As the war increased and economic crisis deepened, many poorer and middle-class citizens fled.

Aside from these waves, Nicaraguan emigration had been relatively limited, at least until 2018. Nicaraguans accounted for just 7 percent of Central American immigrants in the United States in 2019, and less than 1 percent of all U.S. immigrants.

Comparison with the Present

Migration during the Cold War era was significant but has been dwarfed in both absolute and relative terms by the current crisis. An estimated 46,000 Nicaraguan migrants were in Costa Rica due to the war in the 1980s, amounting to about 1 percent of Nicaragua’s then-population of roughly 4 million. Meanwhile, 169,000 Nicaraguans were residing in the United States, according to the 1990 U.S. census.

Today, the more than 192,000 Nicaraguan asylum seekers and refugees in Costa Rica represent nearly 3 percent of Nicaragua’s population of nearly 7 million and nearly 4 percent of Costa Rica’s population of 5.2 million. Those numbers do not include the sizeable number of Nicaraguans living in Costa Rica with other legal status or who are unauthorized. Meanwhile, 257,000 Nicaraguans lived in the United States as of 2021.

Unlike in the past, today’s emigration from Nicaragua has occurred swiftly, in just a few years, and continues to grow.

Future Outlook

This February, Ortega’s government sent 222 former political prisoners to the United States, in a move that a Nicaraguan judge described as a mass deportation. The dissidents, most of whom had been imprisoned in the infamous El Chipote detention center, immediately lost their Nicaraguan citizenship. Among them was Téllez, the revered former guerrilla, who was shocked to find herself on a plane heading north. The release occurred, she said, because Ortega failed to break the prisoners' will. “Every day that I didn’t hang myself,” she told journalists after months in solitary confinement, “was a victory over Ortega.” The U.S. State Department stated there was no negotiation with the Nicaraguan government ahead of time; the flights, though welcomed by supporters, were unilateral. Many of these individuals have found themselves in the Washington, DC area, with little certainty for the future.

In the end, the Ortega government won against the protesters. Barricades set up during the 2018 unrest are now cleared, dissidence has been largely curbed, and Ortega and Murillo seem set to govern for life. In November 2022, Ortega’s FSLN took control of all 153 municipalities, effectively completing the task of transforming the country into a one-party state.

For the average Nicaraguan, history repeats itself. Emigration seen under the brutal Somoza family dynasty has resumed again as Ortega, the heroic guerilla who helped overthrow that regime, has created a family dynasty of his own. As such, it is unlikely that emigration will end any time soon.

Sources

Cordoba, Javier. 2022. Costa Rica Tightens Overwhelmed Asylum System. Associated Press, December 14, 2022. Available online.

Diaz Lopez, Karen. 2021. Nicaraguans Migrate to Costa Rica Despite Covid and Barriers. Havana Times, February 21, 2021. Available online.

Fulwood III, Sam. 1990. INS Would Encourage Nicaraguans to Depart. The Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1990. Available online.

Government of Mexico. 2022. Solicitudes. Government of Mexico fact sheet, Mexico City, December 2022. Available online.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). 2018. IACHR Confirms Reports of Criminalization and Legal Persecution in Nicaragua. Press release, August 2, 2018. Available online.

Pierre Mora, Jean. 2021. Nicaraguans Strive to Support Themselves in Exile in Costa Rica. UN High Commissioner for Refugees, February 12, 2021. Available online.

Reporters without Borders. 2018. Press Freedom in Great Danger after Bad Month in Nicaragua. Press release, December 5, 2018. Available online.

Romero, Simon, J. David Goodman, and Eileen Sullivan. 2022. Mass Migrant Crossing Floods Texas Border Facilities. The New York Times, December 12, 2022. Available online.

Sandoval García, Carlos and Karina Fonseca Vindas. 2020. The Pandemic Reminds Us of Our Interdependence with Nicaragua. Envío, July 2020. Available online.

Seisdedos, Iker and Wilfredo Miranda. 2023. Dora María Téllez and Her 605 Nights of Hell: ‘Every Day that I Didn’t Hang Myself Was a Victory Over Ortega.’ El País, February 12, 2023. Available online.

Selser, Gabriela and Aamer Madhani. 2023. Nicaragua Frees 222 Opponents of Country’s Leader Ortega, Sends Them to U.S. Associated Press, February 9, 2023. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2022. Asylum Decisions. Updated October 2022. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Costa Rica. UNHCR fact sheet, San José, Costa Rica, September 2022. Available online.

UN News. 2020. Nicaragua: After Two Years of Crisis, More than 100,000 Have Fled the Country. UN News, March 10, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2022. Nationwide Encounters. Updated February 6, 2023. Available online.

World Bank. 2022. The World Bank in Nicaragua. Updated October 4, 2022. Available online.