You are here

Standoff at Eagle Pass: A High-Stakes U.S. Border Enforcement Showdown Comes to a Small Texas Park

A member of the Texas National Guard faces migrants in Eagle Pass, Texas. (Photo: 1st Sgt. Suzanne Ringle/Joint Task Force Lone Star)

Escalating tension between Texas and the federal government over border enforcement is raising fears of a looming constitutional crisis and harkening back to Civil War-era questions over the division of federal and state authority on contentious policy issues. Modern-era state efforts to intervene in immigration enforcement, which were largely settled in the federal government’s favor in the early 2010s, are back in dramatic new ways. Most explosively, Texas Governor Greg Abbott in January deployed the state National Guard to block the U.S. Border Patrol from accessing a 2.5-mile-long section of the border in the city of Eagle Pass. The section includes Shelby Park, a 47-acre city park along the Rio Grande named for a Confederate general who fled to Mexico rather than surrender. Border Patrol officials had been using the park for processing encountered migrants. Now, they are effectively locked out of the park, and are mostly unable to access a heavily crossed border area to do their jobs.

In This Article

The Shelby Park episode is the latest and potentially most vexing chapter in a long-simmering standoff between Texas and the federal government, resulting in high-stakes litigation with possible repercussions not just for immigration policy but potentially other areas where federal and state authorities compete. No governor appears to have deployed the state National Guard against federal authorities since 1957, when Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus sought to block nine Black teenagers from entering the all-White Little Rock Central High School under a federal court order, leading President Dwight Eisenhower to federalize the state troops. Texas leaders seem eager for a broader fight, arguing the federal government’s failure to respond to what they deem a migrant “invasion” leaves them no choice but to step in. So far, however, the Biden administration has avoided suing Texas over access to Shelby Park, perhaps to avoid escalating an already tense conflict.

Texas, which has spent more than $10 billion to deter border crossers, now intends to build a state military base in Eagle Pass to house National Guard soldiers from Texas and other states that have pledged to send Guard members in solidarity. Already, Florida National Guard members are patrolling Shelby Park, with other states promising to deploy their forces. Twenty-five Republican governors recently issued a joint statement in support of Texas’s “constitutional right to self defense.”

The Eagle Pass standoff has raised fears of violence against immigrants and federal authorities. Abbott’s “invasion” rhetoric and his comment that “the only thing that we’re not doing is we’re not shooting people who come across the border” have been blamed for inspiring fringe actors. Extremists have made threats against a migrant processing facility in Eagle Pass they cast as a “smuggling hub” and FBI agents recently arrested a Tennessee man who they alleged was planning sniper attacks on migrants and federal agents in Eagle Pass. The “Take Our Border Back” trucker convoy that began in Virginia and ended near Eagle Pass also raised fears of vigilante violence but ended peacefully.

In the short term, the states-versus-Washington feud is likely to ramp up as immigration remains the dominant issue in the upcoming presidential election, and as the Biden administration and Republican leaders spar over the appropriate response to the border crisis. In a sign of the stakes, presumed Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and President Joe Biden planned rival appearances in Eagle Pass and Brownsville respectively on February 29.

The longer-term result of the tussle could be much broader than one election cycle, revisiting longstanding precedent over the limits of state power in immigration matters. Federal supremacy in immigration was affirmed as recently as a 2012 Supreme Court ruling, but the composition of the court is significantly different now, and justices may be willing to revisit the precedent, as they have done with issues such as reproductive rights and affirmative action. This article reviews the recent escalation in federal-state tensions over immigration enforcement and the dispute around Shelby Park.

Simmering State-Federal Animosities over Border Enforcement Come to a Boil

The Eagle Pass standoff, complete with Humvees, fencing, and armed Guard members deployed to keep the Border Patrol at bay, is the culmination of long-running tensions over control of immigration policy. Arizona had been ground zero for state-versus-federal clashes on the issue in the 2000s and early 2010s, but Texas assumed the leadership mantle in 2014, when it led a multistate lawsuit against the Obama administration’s newly announced Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) program, ultimately blocking its implementation. Since then, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has repeatedly sued the Biden administration, including its attempt to end the Migrant Protection Protocols (informally known as the Remain in Mexico program), its guidelines for exercising prosecutorial discretion in immigration enforcement, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, its halting of border fence construction, and its use of the CBP One app appointment process at the border. Beyond taking aim at the executive branch, Paxton in February set his sights on civil society, suing a religious nonprofit in El Paso that shelters border arrivals, accusing Annunciation House of fomenting unauthorized immigration.

The Current Chapter of Texas Activism on Border Enforcement

Abbott opened a new chapter in this state-federal jockeying in 2021, when he launched Operation Lone Star. The state immigration enforcement operation began with an emergency declaration and deployment to border counties of the state National Guard and, later, the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS). Both agencies are tasked with arresting unauthorized migrants on state charges of drug smuggling, human trafficking, and trespassing. The Border Patrol initially collaborated. For instance, Texas authorities would alert the Border Patrol when their cameras detected unauthorized crossings, and Border Patrol officials trained DPS agents on tracking migrants. The state also began collecting funds and planning to build 40 miles of border barrier. And in 2022 it installed tens of thousands of rolls of concertina wire along the border. That year, Texas also began to bus migrants from the border to Democrat-led cities such as Chicago, Denver, New York, and Washington, DC, ultimately relocating more than 100,000 individuals and adding a new political layer to the policy fight. The governor’s office claims that Operation Lone Star has led to more than 500,000 apprehensions of unauthorized immigrants and nearly 40,000 criminal arrests, reportedly mostly for trespassing.

Following complaints that Operation Lone Star was racially profiling people and holding migrants for weeks without charges, the Justice Department in 2022 launched an investigation into whether the operation violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Though that investigation has so far not led to legal action, the federal government did sue Texas last year in response to the state’s installation of 1,000 feet of large buoys separated by circular saw blades to deter Rio Grande crossings. In December, the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered Texas to remove the buoys, ruling that the state action violated a law requiring waterways be navigable. However, the ruling was stayed pending appeal, so the buoys remained in place as of this writing.

Raising the stakes, Texas in 2023 sued to block the Border Patrol from cutting state-installed razor wire, which the agency had regularly done to be able to aid or reach migrants. Texas prevailed at the appellate court, but the U.S. Supreme Court in January vacated the circuit court’s order, for the time being allowing federal officials to remove the wire—though, importantly, not mandating Texas allow them access to do so. Arguments over the buoy and razor-wire cases are winding their way through the lower courts.

Most recently, in December Abbott signed into law a trio of immigration enforcement bills that fund more border barrier construction, increase penalties for human smuggling, and make crossing the border without authorization a state crime. This third law also creates a process for Texas officials to transport to the border unauthorized migrants who have completed their incarceration on state convictions, allowing them to impose felony charges if the individuals do not leave the United States. The Justice Department has sued to block this law from taking effect in March, asserting it violates the federal government’s exclusive authority to enforce immigration laws.

Abbott’s most confrontational move yet came early last month, when the Texas National Guard seized control of Shelby Park. The mayor of Eagle Pass, which owns the park, has said the city did not give the state permission to take it over. Nonetheless, the National Guard sealed off the park with razor wire, fencing, vehicles, and armed forces, preventing the Border Patrol from entering and using the park’s boat ramp to access the Rio Grande. Texas also added additional razor wire to the 2.5-mile stretch of the border and began blocking Border Patrol officials from accessing entry points to the border along the fence. The Border Patrol contends that it can no longer use surveillance or safely access that stretch of the border, including Shelby Park.

The Del Rio border sector, which includes Eagle Pass, was one of the busiest border points last year. In December, as many as 4,000 unauthorized encounters were recorded daily in the Del Rio sector. At times, thousands of migrants waited in an open area adjacent to Shelby Park to be processed by Border Patrol agents. Last year, amid record migrant arrivals, border officials twice shut down one of the two bridges between Eagle Pass and Mexico, to the dismay of local businesses that rely on cross-border traffic. In September, the city declared a state of emergency to make city funds available for expenses related to new arrivals.

Abbott’s use of the National Guard against the federal government has drawn comparisons to the 1957 standoff in Little Rock. Some observers alleged that Abbott was openly defying the Supreme Court by blocking the Border Patrol from cutting the concertina wire, although the court’s order did not require Texas to do anything, but simply removed the lower court’s block on the Border Patrol cutting razor wire. The high court’s ruling, therefore, leaves room for the Border Patrol to cut Texas-installed razor wire and also for Texas to install more wire.

The consequences could be severe. On January 12, Mexican officials reported to the Border Patrol that two migrants were in distress in the river near Shelby Park, and three—including two children—had already died. The agency relayed the message to Texas National Guard members at the Shelby Park gates but were denied access to conduct a rescue. The next day, Mexican officials confirmed that they had rescued the two migrants and recovered three bodies. Texas officials said they had searched the river after receiving the Border Patrol’s alert but did not find the migrants—presumably because Mexico had already come to their rescue. While it is unclear whether the outcome would have been different if the Border Patrol had been able to access the river via the park, the episode underscored the potentially life-and-death stakes at the border. Following this incident, Texas has said it allows the Border Patrol to access the boat ramp and the border generally when migrants are in distress.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has demanded Paxton allow Border Patrol officials back into the park and nearby borderlands, and threatened to refer the matter to the Justice Department. Paxton refused, in a hotly worded response provocatively arguing that the Border Patrol’s access to borderlands, established under federal law, is limited to patrolling to “prevent the illegal entry of aliens into the United States,” and that the Border Patrol is instead facilitating migrants’ entry. Despite Texas’s refusal to back down, the Justice Department has not yet taken legal action.

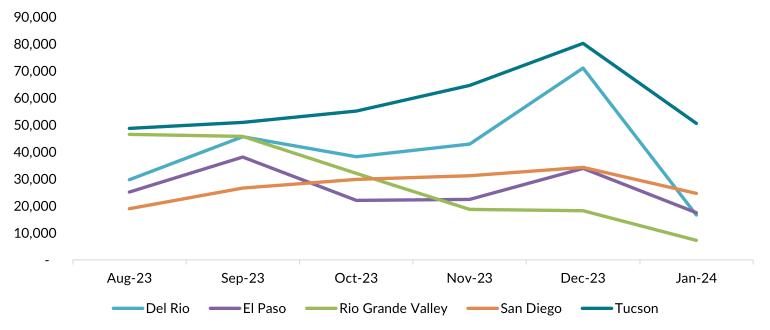

Migrant encounters along the Texas-Mexico border plunged in January. While apprehensions throughout the border fell sharply that month, the dropoff was sharpest in the Del Rio sector (see Figure 1). Biden administration officials attributed the drop to seasonal trends and Mexican authorities’ efforts to slow northward migration after a diplomatic meeting in December, however Texas leaders have credited their restrictive policies.

Figure 1. U.S. Border Patrol Encounters in Select Border Sectors, August 2023-January 2024

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) analysis of data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Nationwide Encounters—FY20 – FY23 Nationwide Encounters by Area of Responsibility,” updated Feb 13, 2024, available online.

A Small Park Takes on Outsized Symbolism

Shelby Park has emerged as a symbol of state antagonism toward the federal government and broader national frustration with the Biden administration’s handling of record encounters at the Southwest border. In early February, several hundred protesters convened for the “Take Our Border Back” rally in nearby Quemado, Texas, which despite initial concerns ended up as a relatively staid gathering of a few hundred people featuring musical performances and speeches bemoaning unauthorized immigration.

The day after the rally, Abbott convened 13 Republican governors in Eagle Pass for a press briefing, surrounded by razor wire and National Guard members. Abbott reiterated his state’s claim to “defend itself and its citizens” from “an invasion” of migrants.

While the Biden administration asserts that immigration enforcement in general—and particularly at the U.S.-Mexico border—is the domain of the federal government, Texas has drawn upon an obscure legal theory to justify its efforts to keep the Border Patrol away. Article 1, Section 10, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution allows states to conduct foreign policy and engage in war without consent of Congress if they are “actually invaded, or in such imminent danger as will not admit of delay.” Abbott and his supporters claim that provides sufficient legal justification for taking action.

Legal scholars have warned that watering down the constitutional threshold for what constitutes an invasion could have dangerous ramifications. It is unclear that irregular migrants, many of whom have travelled thousands of miles to reach the border to seek protection, constitute an invasion. Furthermore, three courts of appeals—the Second, Third, and Ninth—rejected arguments by officials in New York, New Jersey, and California in the late 1990s that a rise in unauthorized border arrivals qualified as an invasion for constitutional purposes.

The Texas legal theory also directly conflicts with the supremacy clause of the Constitution and the recognition by the Supreme Court since the 1880s that the federal government has exclusive authority over immigration matters. The court most recently and pointedly in 2012 reaffirmed that principle in its ruling invalidating much of Arizona’s 2010 SB 1070 law, which would have created new state-level crimes for unauthorized presence and working without federal authorization, as well as allowed local police to arrest anyone they believed to be in the country without status, among other measures. New laws in Florida and Texas aimed at unauthorized immigrants have led to speculation that Republican officials believe a different, more conservative-leaning Supreme Court could revisit the court’s position.

Abbott has further argued the federal government has “broken the compact between the United States and the states,” compelling Texas to defend itself. The claim that the Constitution is a compact between states and the federal government harkens back to the Civil War era, when Southern states argued that Northern states had violated the compact, justifying their secession from the union. This interpretation of the Constitution was ruled incorrect by the Supreme Court after the Civil War.

What might Washington do? Some observers on the left have questioned the Justice Department’s reluctance to sue Texas to restore the Border Patrol’s full access to the border. It is possible the Biden administration is not eager to add to the existing legal fights it is already waging with Texas, or to further heighten political tensions surrounding the issue. The federal government could also federalize the Texas National Guard, as Eisenhower did in Little Rock in 1957. Yet some have urged restraint, arguing that all legal options should be exhausted before considering a step that would further inflame the situation.

On the right, commentators have compared Texas’s actions to “sanctuary” policies issued by states and localities, which they say likewise impede federal immigration enforcement. However, while California and other jurisdictions limit cooperation with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), they do not outright block ICE from arresting removable noncitizens in their jurisdictions or carrying out their basic duties.

Court rulings on the buoy and razor-wire cases remain pending, and the lawsuit against the new Texas immigration laws is in early stages. All this litigation is likely to be protracted, and the losing side is sure to appeal adverse rulings. The Justice Department could sue Texas over Operation Lone Star generally, following its civil-rights investigation, or over the state’s actions at Shelby Park, but so far it seems uninterested in doing so.

Texas may have myriad goals in its antagonism of Washington. The Biden administration’s border management challenges have become a key weakness for Democrats in this election year. Abbott may want to keep immigration high on the national agenda to support fellow Republicans and may see conflict with the administration as helpful to his own political ambitions. Alternatively, state leaders may be simply fed up with the challenges created by high numbers of migrant arrivals for Texas cities and the state, and are using every means they can to try to reduce the numbers. In either case, it is reasonable to expect more state-led enforcement, litigation against federal actions perceived as encouraging high migration, and pressure on the administration through loud rhetoric and continued media coverage.

The administration faces two choices. It could be more forceful in trying to restore the Border Patrol’s access to the border, although this could escalate the conflict, thereby drawing more national attention and hardening opposition. Or it could remain quiet, in the hopes that media coverage dries up and Texas eventually backs off.

While the politics play out, the lawsuits, if they end up overturning or revising well-established legal precedents, may have a much deeper impact on the balance between state and federal authority. Future rulings that support state intervention in what has traditionally been primarily the province of the federal government could embolden state leaders—of varied political persuasions—who have already shown an interest in acting on hot-button issues including reproductive rights, environmental protection, marijuana legalization, gun control, and public education.

Sources

Abbott, Greg. 2024. X post. January 24, 2024, 2:14 pm. Available online.

Ainsley, Julia. 2024. Why Isn’t the Biden Administration Suing Texas for Taking Over the Job of Border Patrol? NBC News, February 6, 2024. Available online.

Calderon, Ricardo E. 2023. City of Eagle Pass Declares Local State of Disaster Due to Migrant Surge. Eagle Pass Business Journal, September 22, 2023. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Jessica Bolter. 2021. Texas Once Again Tests the Boundaries of State Authority in Immigration Enforcement. Migration Information Source, June 29, 2021. Available online.

Coronado, Acacia. 2024. What to Know as Republicans Governors Consider Sending More National Guard to the Texas Border. Associated Press, February 1, 2024. Available online.

De La Rosa, Pablo. 2024. Texas Is Building a Base to House National Guard Troops to Police the Border. National Public Radio, February 19, 2024. Available online.

Department of Homeland Security v. State of Texas. 2024. No. 23A607. Supreme Court of the United States, Supplemental Memorandum Regarding Emergency Application to Vacate the Injunction Pending Appeal, January 12, 2024. Available online.

Flores, Rosa, Holly Yan, Sara Weisfeldt, and Devan Cole. 2024. What We Know about the Drownings of 3 Mexican Migrants Near Eagle Pass, Texas. CNN, January 16, 2024. Available online.

García, Uriel J. 2023. Gov. Greg Abbott Signs Bill Making Illegal Immigration a State Crime. The Texas Tribune, December 18, 2023. Available online.

Herrera, Jack. 2024. Border Patrol and Texas Troopers Were Once the Best of Friends. What Happened? Texas Monthly, February 1, 2024. Available online.

McCullough, Jolie. 2022. Texas’ Border Operation Is Meant to Deter Cartels and Smugglers. More Often, It Imprisons Lone Men for Trespassing. The Texas Tribune, ProPublica, and The Marshall Project, April 4, 2022. Available online.

Molestina, Ken. 2024. Governor Abbott's Operation Lone Star Touts Thousands of Arrests, $10 Billion Cost. CBS News Texas, January 22, 2024. Available online.

Montoya-Galvez, Camilo. 2023. Migrants Cross U.S. Border in Record Numbers, Undeterred by Texas' Razor Wire and Biden's Policies. CBS News, December 24, 2023. Available online.

---. 2024. Biden Administration Warns It Will Take Action if Texas Does Not Stop Blocking Federal Agents from U.S. Border Area. CBS News, January 15, 2024. Available online.

---. 2024. Migrant Crossings Fall Sharply along Texas Border, Shifting to Arizona and California. CBS News, February 8, 2024. Available online.

Office of the Texas Governor. 2024. America’s Governors Band Together to Support Operation Lone Star. Press release, February 9, 2024. Available online.

---. 2024. Texas Upholds Constitutional Right to Defend Itself from Invasion. Press release, February 23, 2024. Available online.

Paxton, Ken. 2024. Letter from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton to General Counsel of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Jonathan E. Meyer. January 17, 2024. Available online.

---. 2024. Letter from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton to General Counsel of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Jonathan E. Meyer. January 26, 2024. Available online.

Republican Governors Association. 2024. Republican Governors Band Together, Issue Joint Statement Supporting Texas’ Constitutional Right to Self-Defense. Press release, January 25, 2024. Available online.

Somin, Ilya. 2024. Texas Is Wrong to Equate Immigration and Drug Smuggling with "Invasion.” Reason, August 10, 2023. Available online.

Stern, Mark Joseph. 2024. GOP Governors Invoke the Confederate Theory of Secession to Justify Border Violations. Slate, January 26, 2024. Available online.

Trevizo, Perla. 2022. Justice Department Is Investigating Texas’ Operation Lone Star for Alleged Civil Rights Violations. The Texas Tribune and ProPublica, July 6, 2022. Available online.

Villagram, Lauren. 2023. Ken Paxton: 6 Times the Now-Suspended Texas AG Sued over Immigration Policies. El Paso Times, July 13, 2023. Available online.

Vladeck, Stephen. 2024. Governor Abbott’s Perilous Effort at Constitutional Realignment. Lawfare, January 29, 2024. Available online.

---. 2024. What’s Really Happening in Biden vs. Abbott vs. the Supreme Court. The New York Times, February 1, 2024. Available online.

Zimmer, Thomas. 2024. Texas' Border Defiance Might Be the First Volley in a New Civil War. The UnPopulist, February 5, 2024. Available online.