You are here

Biden at the Three-Year Mark: The Most Active Immigration Presidency Yet Is Mired in Border Crisis Narrative

President Joe Biden signs an executive order. (Photo: Erin Scott/White House)

Editor's Note: This article was updated on January 22, 2024 to correct the agency responsible for changes to the H-1B visa lottery system.

By taking 535 immigration actions over its first three years, the Biden administration has already outpaced the 472 immigration-related executive actions undertaken in all four years of President Donald Trump’s term. Partly as result of these efforts, legal immigration is returning to and in some cases surpassing pre-pandemic levels, including refugee admissions on pace to reach the highs of the 1990s; a new border process seeking to discourage irregular arrivals has been adopted; temporary humanitarian protections have been extended to hundreds of thousands of migrants; and enforcement priorities have been focused on narrower categories of unauthorized immigrants. Combined, these changes have fulfilled some of President Joe Biden’s campaign promises, helped bolster the U.S. economy, and reduced fears of seemingly arbitrary enforcement against removable noncitizens.

Yet the border crisis confronting the Biden administration has left the most activist presidency yet on immigration accused of inaction by critics—to the extent that the House of Representatives this month launched impeachment proceedings against the administration’s Homeland Security secretary. The U.S. southern border has witnessed a record of at least 6.3 million migrant encounters at and between ports of entry since Biden took office in January 2021, according to data from the Office of Homeland Security Statistics, resulting in more than 2.4 million migrants allowed into the country. Most of these individuals are in active removal proceedings in immigration court, in which they can claim asylum as a defense against removal. Even some of Biden’s fellow Democrats have begun advocating for more stringent border control, adding a new dimension to immigration politics in a presidential election year when the issue is sure to be a defining one between the two political parties.

The speeded pace of executive actions taken by the current and last administration is, in part, a response to continued inaction in Congress, which has not passed a major immigration overhaul in nearly three decades. However, as of this writing, the president was engaged in negotiations with congressional leaders for a $110 billion package that would provide aid for Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan in exchange for tightened border controls and asylum eligibility. These talks were also partly a response to the administration’s actions, as congressional leaders were discussing limiting the president’s ability to make certain immigration changes, especially granting immigration parole, which permits temporary stay in the country and work authorization.

In This Article

-

The administration has deployed a series of carrot-and-stick measures at the border

-

A swelling number of individuals hold "twilight" legal statuses that do not lead to a green card

-

Washington has relied on partner countries in Latin America and the Caribbean

-

Refugee resettlement is on pace to be the highest in decades

-

Legal immigration is at new highs after the pandemic-induced slowdowns

-

In an election year, immigration remains a political vulnerability

The Biden administration’s 535 executive actions through January 17, as calculated the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), were issued in one of the most turbulent migration periods within the Western Hemisphere and indeed globally in recent history. As such, the actions have covered a wide spectrum. When the administration lifted the COVID-19-related Title 42 expulsions authority in May 2023, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) replaced it with a system of incentives for asylum seekers arriving at ports of entry and disincentives for those crossing between ports of entry without authorization, among other changes. Because of temporary protections, such as parole, extended to hundreds of thousands of arriving migrants, approximately 2.3 million people living in the United States hold liminal legal statuses, a ballooning population in limbo that may prove an enduring legacy of the Biden administration. Another potential sea change is increased coordination with countries in Latin America, designed to bring migration opportunities closer to individuals’ origin countries. And some, though not most, of the administration’s actions are part of an effort to undo changes introduced during the Trump administration.

This article reviews the major immigration actions during the Biden administration’s first three years, focusing on border enforcement, interior enforcement and impacts on U.S. cities, humanitarian protection, the immigration courts, and legal admissions.

The Inescapable Southwest Border

To respond to the record migrant encounters in fiscal year (FY) 2022, which were topped the following year, the Biden administration fundamentally changed its policy on border enforcement. It combined strategies to incentivize arrivals at ports of entry, use stricter enforcement and narrow access to asylum to disincentivize arrivals between official border crossings, and establish new temporary pathways for some nationality groups. One year on, the challenge has persisted; on just one day—December 19—a record 12,000 migrants arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border without authorization to enter.

A Brief Expansion of Title 42 Expulsions

Although Biden entered office promising to end the use of Title 42, which prevented individuals from being able to seek asylum by permitting rapid expulsions, court challenges and on-the-ground realities interfered, prompting outcry from immigrant advocates that the president’s border posture was little different than Trump’s. In late 2022 and early 2023, the administration expanded Title 42 to Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans, and paired the move with a new humanitarian parole program allowing nationals of those countries to apply for parole from outside the United States. The administration also announced that migrants would have to schedule their arrival at a port of entry through the CBP One mobile app used by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

In practice, Title 42 was used primarily for nationals of Mexico and Central America. Between January and May, just 34 percent of Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans encountered by the U.S. Border Patrol between ports of entry were subject to Title 42, compared to 68 percent of Mexicans and Central Americans. While Title 42 was in effect from March 2020 to May 2023, the Border Patrol carried out 2.8 million expulsions.

A New Approach

In May, the administration announced a second batch of carrot-and-stick policies. The post-Title 42 plan rests on a new Circumvention of Lawful Pathways rule, which incentivizes arrivals at ports of entry and disincentivizes irregular crossings by making migrants without a CBP One appointment ineligible for asylum unless they had applied for and been denied protection in another country, arrived through a parole program, or qualified for an exception under the rule.

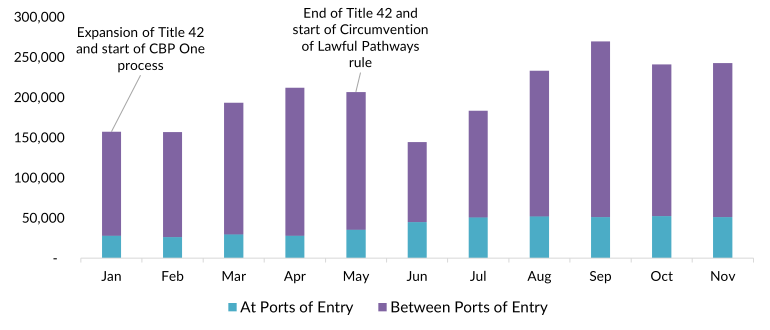

The results of these policy changes have thus far been mixed (see Figure 1). On the one hand, the use of CBP One has increased the number of migrants processed at ports of entry, up more than fourfold from 2019. In FY 2021, just 4 percent of unauthorized migrants at the southwest border were encountered at ports of entry; in FY 2023, that number rose to 17 percent. Moreover, the parole program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans has been used widely; through November, 297,000 people arrived under the program—112,000 Haitians, 76,000 Venezuelans, 60,000 Cubans, and 47,000 Nicaraguans. The program’s ability to direct unauthorized border arrivals to head to an official port of entry has varied by nationality, however. While 99 percent of Haitians encountered during FY 2023 arrived at ports of entry, just 25 percent of Venezuelans did so.

Figure 1. Migrant Arrivals at and between Ports of Entry, 2023

Note: Migrant encounters at ports of entry are managed by U.S. Custom and Border Protection’s Office of Field Operations; those between ports of entry are managed by the U.S. Border Patrol.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Nationwide Encounters,” updated December 22, 2023, available online.

On the other hand, irregular arrivals have remained high, and processing is an immense challenge for DHS, despite a huge shift of resources and personnel to the border. Application of the Circumvention of Lawful Pathways rule has been quite limited; due to capacity constraints, just 7 percent of encounters between May and September were screened under this rule. Faced with overwhelmed border processing facilities, an increasing diversity of nationalities that complicates swift removal, and more families, authorities have released many migrants into the country to undergo removal proceedings in immigration court.

U.S. Interior Feels Reverberations from the Border

When it was in place, Title 42 resulted in fewer removals by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In FY 2023, ICE removed 143,000 migrants—almost double the number in FY 2022 (72,000), but still well below the 234,000 average annual removals during Trump’s term and 344,000 average annual removals under President Barack Obama. ICE also expelled 63,000 migrants under Title 42 before the policy ended.

After Title 42 ended, DHS’s removals and returns ballooned, outpacing numbers in pre-pandemic years. From May through December, DHS carried out more than 470,000 removals or returns, mostly of migrants who crossed the southwest border without authorization. Returns to Mexico may account for some of this sharp rebound, given the country’s acceptance of up to 30,000 Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans per month. ICE’s detention capacity increased after the end of COVID-19 protocols, with average daily detention rising from 23,000 in FY 2022 to 28,000 in FY 2023.

Still, changing realities and finite resources have strained operations. In FY 2023, there were 6.2 million cases on ICE’s docket of nondetained migrants, up from 4.8 million in FY 2022. ICE monitors individuals on this docket through check-ins and the use of alternatives to detention (ATD) technology, such as restricted-use cellphones or ankle monitors. Yet ICE’s use of ATDs, after years of expansion, decreased by 39 percent in FY 2023, due in part to court orders and a lack of resources.

DHS also established the Family Expedited Removal Management (FERM) program in May in response to rising numbers of arrivals of families, who must be handled differently than single adults (822,000 individuals arrived as part of families at and between ports of entry at the southwest border in FY 2023, a 47 percent increase over the 561,000 in FY 2022). Under the FERM program, ICE places families on electronic monitoring and processes them for expedited removal after they have reached their U.S. destination. Families that cannot show a credible fear of persecution or torture are quickly removed. But FERM and other case management programs have so far had minimal impact, due to resource and capacity constraints. As of September, only about 1,600 families had been enrolled in the program.

Interior Cities Feel the Impact

With most migrants moving onward from the border after release, states and localities in the interior have begun to acutely feel the fiscal impact of high migrant arrivals. In cities such as New York, Chicago, and Denver, mayors and governors from Biden’s own party have become increasingly supportive of more stringent border controls and critical of the lack of federal coordination and reimbursement. Across the United States, a lack of affordable housing has pushed public shelter systems well over capacity, with border arrivals only adding to the pressures. Additionally, costs associated with education, health care, and access to legal services have further strained municipal budgets.

To address the mounting demand to expedite work permits for recent arrivals, the administration has granted liminal or “twilight” statuses such as parole and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) that provide temporary relief from removal and eligibility for work authorization, sped the processing of applications at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and extended validity periods for work permits issued to asylum seekers, among other steps.

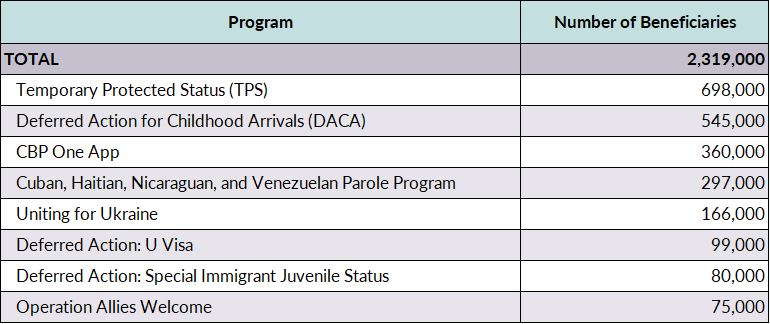

In October, DHS announced that it would redesignate and grant TPS to Venezuelans who entered the country before July 31, 2023, making approximately 472,000 more people eligible for the status. The announcement capped a year of multiple TPS designations and extensions, leading to the highest-ever population of TPS holders: an estimated 698,000 as of September. Potentially hundreds of thousands more are eligible.

The administration also continued other programs that provide migrants with temporary protection from deportation and work authorization. These include Uniting for Ukraine, for people fleeing Russia’s invasion; Operation Allies Welcome (which has transitioned to Operation Enduring Welcome), for Afghans fleeing the Taliban; and deferred action programs for certain vulnerable populations awaiting visas from inside the United States. The administration also launched a new deferred action program to benefit unauthorized immigrants engaged in labor disputes with their employers; DHS received more than 2,000 requests through the program in 2023.

In September, a federal district court again found the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program unlawful, but allowed current DACA holders to maintain their status while appeals are ongoing. Migrants processed at the border via the CBP One app and parolees through the aforementioned program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans also receive temporary protection from deportation and eligibility for work authorization.

Table 1. U.S. Immigrants with Twilight Statuses, 2023

Notes: Table shows the number of holders of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) as of September 2023. Numbers for the CBP One app and the parole program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans are through November 2023. CBP One numbers are for successfully scheduled appointments made through the app; not every appointment results in an individual being processed into the country. The Uniting for Ukraine number is through November 8, 2023. Numbers for the two types of deferred action indicate the number of people initially granted deferred action. Deferred action for U Visa applicants shows the number of holders as of September 2023. Deferred action for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status shows the number of holders as of April 2023. The number of Afghans assisted through Operation Allies Welcome is as of March 2023. Some grantees may have obtained a different immigration status, including asylum, TPS, or lawful permanent residence.

Sources: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Count of Active DACA Recipients as of September 30, 2023,” accessed January 2, 2024, available online; USCIS, “Number of Form I-918 Petitions for U Nonimmigrant Status By Fiscal Year, Quarter, and Case Status, Fiscal Years 2009-2023,” accessed January 3, 2024, available online; CBP, “CBP Releases November 2023 Monthly Update” (press release, December 22, 2023), available online; U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman, Annual Report 2023 (Washington, DC: DHS, 2023), available online; DHS, “Weekly Partner Update: Uniting for Ukraine (U4U)” (November 8, 2023); Jill H. Wilson, Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2023), available online; the Special Immigrant Juvenile Status number comes from panel discussion at the spring conference of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, Washington, DC, April 27-28, 2023

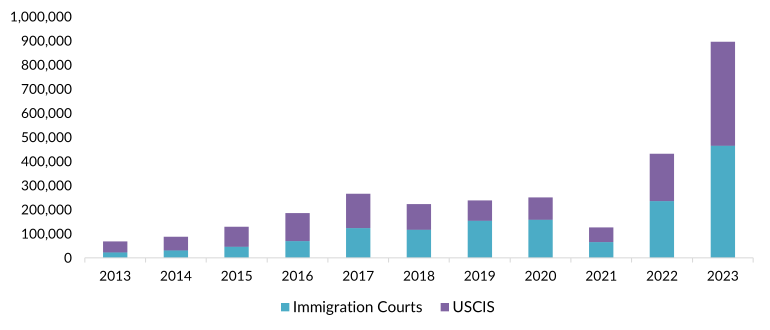

Together, these initiatives have provided approximately 2.3 million people with liminal statuses. The designations do not have a path to permanent U.S. residence; thus, many immigrants will likely end up applying for asylum. This swelling population is one reason why asylum cases are at record highs (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Asylum Applications by Location of Filing, FY 2013-23

Notes: Data represent the number of applications filed; a single application can cover multiple individuals. The U.S. immigration court system is generally responsible for asylum seekers applying at the border or who file claims after being apprehended as an unauthorized immigrant. USCIS is responsible for cases filed by individuals with a visa or already present in the United States. Under a May 2022 asylum officer rule, USCIS may also decide certain asylum claims from apprehended migrants.

Sources: Andorra Bruno, Immigration: U.S. Asylum Policy (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2019), available online; Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), Defensive Asylum Applications, (Washington, DC: EOIR, 2023), available online; USCIS, Affirmative Asylum Statistics FY 2019 (Washington, DC: USCIS, 2023), available online; USCIS, Asylum Quarterly Engagement (Washington, DC: USCIS, 2023), available online; USCIS, Number of Service-Wide Forms Fiscal Year to Date by Quarter and Form Status Fiscal Year 2020 (Washington, DC: USCIS, 2020), available online; USCIS, Number of Service-Wide Forms Fiscal Year to Date by Quarter and Form Status Fiscal Year 2021 (Washington, DC: USCIS, 2021), available online; USCIS, Number of Service-Wide Forms by Quarter, Form Status, and Processing Time July 1, 2022 – September 30, 2022 (Washington, DC: USCIS, 2022), available online.

In 2023, DHS pulled personnel and resources to screen applicants at the border rather than adjudicate asylum claims at offices inside the country. As of November, 1.1 million asylum cases were in a backlog at USCIS, and another 938,000 applications were pending at the immigration courts. Of the 431,000 asylum applications filed at USCIS in FY 2023, 62 percent came from nationals of Latin American and Caribbean countries; Venezuelans (22 percent), Cubans (18 percent), Colombians (8 percent), Nicaraguans (8 percent), and Haitians (6 percent) were the largest nationalities. Nationality data are not available for asylum applications filed at immigration courts.

Responding to record migration from elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere, the Biden administration has relied on partner countries in Latin America and the Caribbean to slow movement and accept returns of their citizens. The State Department negotiated with countries in the region to open Safe Mobility Offices (SMOs) designed to provide lawful migration pathways to a limited number of eligible migrants, thus discouraging dangerous journeys and irregular border arrivals. Since June, SMOs have opened in Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Guatemala, jointly run by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). SMOs only cater to migrants who are otherwise eligible to enter the United States through existing channels such as family reunification or employment sponsorship, or as refugees (the offices also provide migration pathways to Canada and Spain). While DHS initially estimated that the SMOs would process 5,000 migrants per month, operations remain nascent. As of January, about 3,000 refugees in total had arrived in the United States via the SMOs, with another 9,000 approved for admission to the United States.

In tandem with the announcement of the SMOs, DHS revealed plans for family reunification programs for Colombians, Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans. Existing programs for Cubans and Haitians were also streamlined, and a program for Ecuadorians was added the same day the country agreed to host an SMO. These programs allow family members with existing family sponsorship applications to travel to the United States with parole while waiting in line for a green card. Thus, unlike the other parole programs, these provide a pathway to permanent U.S. residence. As of January, approximately 3,000 individuals had arrived through these programs.

Restored Prosecutorial Discretion Guidelines and Streamlined Courts

While record encounters at the southwest border have dominated the headlines, the Biden administration’s success in advancing its interior enforcement agenda has received minimal attention. This change is one area which has perhaps had the most impact on the daily lives of immigrants and their families in the United States.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court revived a major administration policy by allowing the use of enforcement guidelines that prioritize the arrest and removal of noncitizens who pose a threat to public safety, national security, or border security. The guidance gives authorities discretion to consider mitigating and aggravating factors in cases, and to suspend enforcement actions against low-priority individuals who have been in the country for a long period. The prosecutorial discretion guidelines, issued in September 2021, had been blocked by the courts for a year. During that time, ICE attorneys nonetheless exercised discretion on a case-by-case basis and agreed to the dismissal or pause of 119,000 cases in FY 2023.

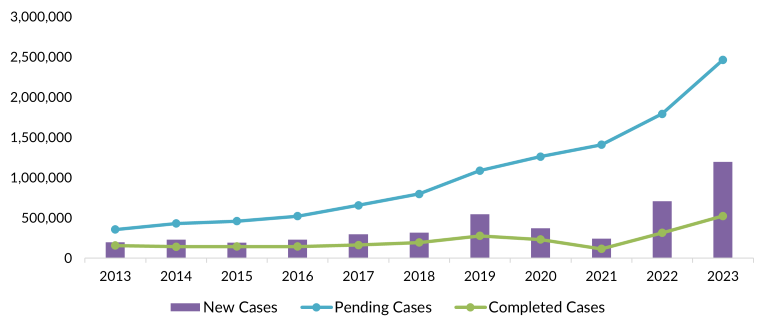

On a parallel track, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) has sought to address huge backlogs by allowing immigration judges to take nonpriority cases off the docket. In FY 2023, 208,000 removal cases were dismissed or terminated. These docket management strategies seem to have been particularly applied in asylum cases, which as of October made up more than one-third of the courts’ 2.5 million cases (see Figure 3). In FY 2023, 154,000 asylum cases were closed or paused, up from 110,000 in FY 2022. Still, the courts received 1.2 million new cases in FY 2023, many from recent border arrivals, meaning judges will remain overwhelmed in the years ahead unless significant policy changes or vast new resource infusions occur. Given the pressures, it is notable that the courts completed a record 523,000 cases in FY 2023.

Figure 3. Completed, New, and Pending Cases at the Executive Office of Immigration Review, FY 2013-23

Source: EOIR, Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions (Washington, DC: EOIR, 2023), available online.

Refugee Resettlement on the Rebound

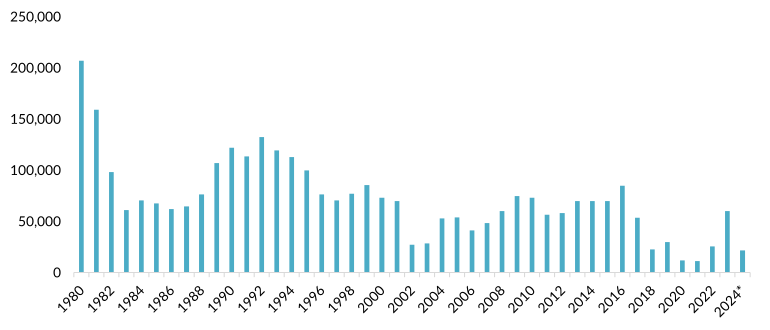

Since taking office, the Biden administration has rebuilt the refugee resettlement system after admissions hit record lows under Trump. Progress was initially slow, with just 25,500 refugees resettled in FY 2022 out of a target of 125,000. In FY 2023, 60,000 refugees were resettled—the most since Obama’s final year in office, when 85,000 refugees arrived. The system is on track to pass that number in FY 2024 and reach the largest refugee admissions since the mid-1990s. To achieve that goal, the United States has expanded its network of nonprofit partners that refer refugees, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean, from where the administration aims to admit up to 50,000.

Figure 4. U.S. Refugee Admissions, FY 1980-24*

* FY 2024 data are for the first three months of the fiscal year, through December 2023.

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) Migration Data Hub, “U.S. Annual Refugee Resettlement Ceilings and Number of Refugees Admitted, 1980-Present,” accessed January 10, 2024, available online.

The State Department had set a 2023 goal of admitting 5,000 refugees through its new Welcome Corps initiative, but just 85 refugees had entered through the program in calendar 2023. Welcome Corps allows U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents to sponsor and support refugees in the place of traditional resettlement agencies, so long as they raise $2,425 per refugee, pass background checks, and submit an assistance plan.

Post-Pandemic, Legal Immigration at New Highs

Following sharply depressed legal immigration due to COVID-19 restrictions, legal immigration admissions to the United States soared in FY 2023. Initial data suggest that nearly 1.2 million immigrants became lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green-card holders) in FY 2023, exceeding the 1.1 million annual average over the decade before the pandemic. The State Department issued 10.4 million nonimmigrant visas that year, the most since 2015 and up from 6.8 million in FY 2022. Additionally, 883,000 immigrants naturalized in FY 2023, down slightly from the 964,000 in FY 2022 but otherwise the most since FY 2008.

Pandemic-driven adaptations accelerated modernization of the immigration system and facilitated the high numbers of visa issuances. Increasing the types of applications that can be filed online, holding remote hearings, waiving interviews, and extending documents’ validity periods have all resulted in faster visa approvals.

Nonetheless, enormous backlogs remain and wait times for some applications stretch for years, in part due to the focus on processing applications for recent border arrivals and would-be parolees. The total green-card backlog reached 7.6 million in November, according to estimates from the Bipartisan Policy Center, due to processing delays as well as annual visa caps set by Congress. At USCIS, more than 9 million applications were waiting to be processed for a range of benefits when FY 2023 ended.

To curb fraud, DHS announced changes in October to the H-1B visa lottery for specialty workers, whereby employers will no longer be advantaged for putting in applications for multiple workers, and workers will have more freedom to pick among employers willing to sponsor them. Additionally, a State Department pilot program launching this month will allow 20,000 H-1B visa holders to renew their visas stateside, without having to return to a consulate in their origin country.

Immigration Remains an Election-Season Vulnerability

The Biden administration entered office with an activist and ambitious immigration plan. By drawing a strong distinction with the Trump administration’s signature restrictive immigration agenda, Biden’s team had created an expectation of a more welcoming immigration policy, including fewer blanket border restrictions. While the administration has had considerable success in providing protection to hundreds of thousands of migrants already in the country and in returning the United States to its previous levels of legal admissions (including resettled refugees), its ability to manage growing border challenges has been sorely tested.

Global push factors including war, violence, instability, human-rights abuses, natural disasters, poverty, and economic spirals triggered by the pandemic reached unprecedented levels in 2023 and were reflected in the number of migrant arrivals to the United States. The ability of social media to direct migrants' travel and smuggling organizations’ sophisticated operations and ability to propagate information (both factual and not) have also been formidable challenges. Pull factors include a U.S. labor market with millions of job openings as well as difficulties speedily returning migrants ineligible to stay due to overwhelmed border processing and the inability to decide asylum cases in a timely manner.

U.S. laws and enforcement resources were largely developed for a different era, and are no match for today’s border arrivals, which are more diverse in nationality, arriving as families in greater numbers, and with unprecedented protection needs. Existing court mandates, new lawsuits, and the constant threat of litigation limit the administration’s options. Looming in the background is this year’s presidential election—likely a rematch of 2020—in which immigration will once again play an outsized role. The Biden administration has struggled to draw attention to its significant immigration successes, instead contending with the ever-present pressures at the border. Changing the national narrative may be its most difficult challenge to confront.

The authors thank Faith Williams and Julian Montalvo for research assistance.

Sources

American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA). 2023. Featured Issue: Prosecutorial Discretion. August 28, 2023. Available online.

Bruno, Andorra. 2019. Immigration: U.S. Asylum Policy. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Kathleen Bush-Joseph. 2023. Biden at the Two-Year Mark: Significant Immigration Actions Eclipsed by Record Border Numbers. Migration Information Source, January 26, 2023. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Julia Gelatt. 2023. Antiquated U.S. Immigration System Ambles into the Digital World. Migration Information Source, November 29, 2023. Available online.

Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). Defensive Asylum Applications. Washington, DC: EOIR. Available online.

---. 2023. FY 2023 Decision Outcomes. Washington, DC: EOIR. Available online.

---. 2023. Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions. Washington, DC: EOIR. Available online.

---. 2023. Total Asylum Applications. Washington, DC: EOIR. Available online.

Hesson, Ted and Mica Rosenberg. 2023. New US Refugee Program Lets Americans Choose Who to Sponsor. Reuters, December 19, 2023. Available online.

Law360. 2023. H-1B Visa Cap Reached For 2024. Law360, December 13, 2023. Available online.

M.A et al v. Alejandro Mayorkas. 2023. Declaration of Blas Nuñez-Neto, Assistant Homeland Security Secretary, Border and Immigration Policy. U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia, October 2023.

Malde, Jack, Theresa Cardinal Brown, and Ben Gitis. 2023. Green Light to Growth: Estimating the Economic Benefits of Clearing Green Card Backlogs. Washington, DC: Bipartisan Policy Center. Available online.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI) Migration Data Hub. N.d. U.S. Annual Refugee Resettlement Ceilings and Number of Refugees Admitted, 1980-Present. Accessed January 10, 2024. Available online.

Salomon, Gisela and Colleen Long. 2024. A New Immigration Policy that Avoids a Dangerous Journey Is Working. But Border Crossings Continue. Associated Press, January 5, 2024. Available online.

Stern, Paul. 2023. End-of-Year Reflection on the State Department’s FY23 Visa Processing Achievements and What Needs to Be Done Next. Think Immigration, December 5, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2020. Number of Service-Wide Forms Fiscal Year to Date by Quarter and Form Status Fiscal Year 2020. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2021. Number of Service-Wide Forms Fiscal Year to Date by Quarter and Form Status Fiscal Year 2021. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2022. Number of Service-Wide Forms by Quarter, Form Status, and Processing Time July 1, 2022 - September 30, 2022. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2023. Asylum Quarterly Engagement. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2023. Extension and Redesignation of Venezuela for Temporary Protected Status. Federal Register 88, no. 190. October 3, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Family Reunification Parole Processes. Updated January 2, 2024. Available online.

---. 2023. Number of Service-Wide Forms by Quarter, Form Status, and Processing Time July 1, 2023 - September 30, 2023. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2024. Asylum Division Monthly Statistics Report. Fiscal Year 2024. November 2023. Updated January 3, 2024. Available online.

---. N.d. Count of Active DACA Recipients as of September 30, 2023. Accessed January 2, 2024. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2023. CBP Releases November 2023 Monthly Update. Press release, December 22, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Nationwide Encounters. Updated December 22, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2023. DHS Conducts Removal Flights to Venezuela and Central America. Press release, December 27, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. DHS Continues to Prepare for End of Title 42; Announces New Border Enforcement Measures and Additional Safe and Orderly Processes. Press release, January 5, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Operation Allies Welcome: Afghan Parolee and Benefits Report: Fiscal Year 2022 Report to Congress. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

---. 2023. Weekly Partner Update: Uniting for Ukraine (U4U). November 8, 2023.

---. 2024. 2023 Year in Review: Secretary Mayorkas Champions Department-Wide Efforts to Save Lives and Prepare for 21st Century Security Challenges. Press release, January 9, 2024. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman. 2023. Annual Report 2023. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2023. ICE Annual Report: Fiscal Year 2023. Washington, DC: ICE. Available online.

---. 2023. ICE Releases Fiscal Year 2023 Annual Report. News Release, December 29, 2023. Available online.

U.S. State Department. 2023. Fact Sheet – Launch of Welcome Corps- Private Sponsorship of Refugees. Fact sheet, January 19, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Remarks: Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas at a Joint Press Availability. Press release, April 27, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Visa Operations Bring Record Achievements Worldwide. Press release, November 28, 2023. Available online.

---. 2024. World Visa Operations: Update. Updated January 2, 2024. Available online.

U.S. State Department, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), Refugee Processing Center (RPC). 2024. Refugee Admissions Report. Updated January 5, 2024. Available online.

Wilson, Jill H. 2023. Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

White House. 2023. Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Border Enforcement Actions. Fact sheet, January 5, 2023. Available online.