You are here

Antiquated U.S. Immigration System Ambles into the Digital World

USCIS employees at work. (Photo: USCIS)

Notorious for its reliance on antiquated paper files and persistent backlogs, the U.S. immigration system has made some under-the-radar tweaks to crawl into the 21st century, with the COVID-19 pandemic serving as a catalyst. Increased high-tech and streamlined operations—including allowing more applications to be completed online, holding remote hearings, issuing documents with longer validity periods, and waiving interview requirements—have resulted in faster approvals of temporary and permanent visas, easier access to work permits, and record numbers of cases completed in immigration courts.

While backlogs have stubbornly persisted and even grown, the steps toward modernization at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the State Department have nonetheless led to a better experience for many applicants seeking immigration benefits and helped legal immigration rebound after the drop-off during the COVID-19 pandemic. Swifter processes in the immigration courts have provided faster protection to asylum seekers and others who are eligible for it, while also resulting in issuance of more removal orders to those who are not.

Yet some of these gains may be short-lived. Some short-term policy changes that were implemented during the pandemic have ended and others are about to expire, raising the prospect of longer wait times for countless would-be migrants and loss of employment authorization for tens of thousands of immigrant workers. Millions of temporary visa applications may once again require interviews starting in December, making the process slower and more laborious for would-be visitors. This reversion to prior operations could lead to major disruptions in tourism, harm U.S. companies’ ability to retain workers and immigrants’ ability to support themselves, and create barriers for asylum seekers with limited proficiency in English.

The recent changes have been a boon to many immigrants, short-term visitors, U.S. employers, and Americans petitioning for loved ones to join them; they have also brought some transparency to often opaque government processes. At the same time, some operational shifts may have created challenges for vulnerable populations including those with limited access to or familiarity with technology. This article reviews the recent changes in U.S. immigration operations and greater reliance on internet-enabled operations.

New Flexibilities to Accommodate Pileups of Applications

In the face of massive processing backlogs that ballooned during the pandemic, USCIS and the State Department modified some operations, including waiving interview requirements for many temporary visas and extending work permits for longer periods. This had a marked effect on the U.S. immigration system by reducing visa bottlenecks and helping tens of thousands of noncitizens stay employed, but some temporary changes have already started to be reversed.

Waivers of Interview Requirements for Temporary Visas

Delays for visa interviews abroad mounted after U.S. consulates closed for most in-person services in early 2020, with the arrival of the pandemic and widespread disruption to government services. Even after offices reopened, social distancing measures and local restrictions severely limited processing capacity in many places. By December 2021, temporary visa appointment wait times stretched to more than a year in Toronto, for example, and were available only on an emergency basis for some of the busiest U.S. consulates in India, including Kolkata, Mumbai, and New Delhi.

Under pressure from businesses eager for foreign workers, the State Department in August 2020 began waiving in-person interviews for certain applicants renewing temporary visas that had expired within the prior 24 months. (In March 2021, waivers were extended to those whose visas had expired in the prior 48 months.) Starting in December 2021, consular officers could also waive interviews for certain temporary work, student, and exchange visitor visas (F, H, J, L, M, O, P, and Q) for individuals who had previously without incident been issued any kind of U.S. visa or travelled to the country through the Visa Waiver Program, had never been denied a visa (or the denial was overturned), and had no apparent ineligibility. (Nationals of countries designated by the United States as state sponsors of terrorism cannot have their interviews waived.) This interview waiver authority is set to expire at the end of December.

Through these waivers, 48 percent of the 6.8 million nonimmigrant visas issued in fiscal year (FY) 2022 were approved without an in-person interview. Wide use of interview waivers helped reduce the very long waits at U.S. consulates abroad. The average wait across consulates for a temporary worker requiring an in-person interview was 30 days at this writing, and 28 days for an international student.

If the authority to waive visa interviews is not renewed, wait times could again balloon, affecting foreign-born workers and their sponsoring employers. Further, consular offices busy interviewing would-be temporary workers and students would likely deprioritize interviews for business visitors and tourists, creating a domino effect that reduces U.S. tourism and its economic benefits.

Even still, interview wait times in some locations remained longer than elsewhere over recent years, due to varying levels of demand and reduced consular capacity. Consulates in India, a major sending country of U.S. high-skilled temporary workers and international students, have experienced particularly long wait times; in November 2022, would-be temporary workers had to wait 351 days for an interview in Mumbai. The State Department responded by allocating more staff to U.S. consulates in India and extending hours for interviews, including to Saturdays. It also redistributed backend visa processing work around the world, such as by shifting some tasks to consular officers in places including China, where pandemic-linked travel restrictions sharply reduced visa applications.

The State Department is also likely to resume revalidating visas inside the United States. Typically, when temporary visa holders wish to travel abroad, they must renew their visas at a U.S. consulate abroad before re-entering the United States. Prior to 2004, they were able to renew their visas inside the United States. This option was paused due to logistical challenges related to new biometrics collection requirements, but beginning in January a limited pilot program will allow 20,000 H-1B visa holders to renew their visas stateside.

Longer Extensions of Work Permits

Approximately 1.6 million applications for employment authorization documents were sitting in a backlog at USCIS as of October 2023, more than double the 676,000 pending in March 2020. A larger number of noncitizens than before are eligible for work permits, including certain spouses of temporary workers, asylum applicants, humanitarian parolees, and beneficiaries of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) programs. Granting work permits to recent migrants has been a major priority for politicians in Massachusetts, New York City, and other places contending with the record numbers of asylum seekers and other migrants coming from the U.S.-Mexico border. Yet delays adjudicating renewals in recent years have meant that many work permits expired, forcing employers to terminate immigrants’ employment or place them on furlough. Some workers had to endure months without income, even as the U.S. economy faced severe labor shortages, particularly in the immigrant-heavy health-care and child-care sectors.

Since September, USCIS has increased the validity length of work permits for asylum applicants, refugees and asylees, and those applying for lawful permanent residence (a green card) from within the United States, among others. New work permits for these applicants are now valid for up to five years, compared to either one or two years in the past. In addition to offering more certainty to immigrants, the move reduces the fees they need to pay for renewals and reduces the USCIS workload.

For many years, USCIS auto-extended work permits for many applicants by 180 days, so long as they had filed a renewal application on time. But in May 2022, approximately 87,000 renewal applications were past or nearing their 180-day auto-extension period, and predictions suggested at least 14,500 additional applicants were on track to lose their work authorization in each successive month. Therefore, the agency increased auto-extensions to 540 days, allowing tens of thousands of workers to return to their jobs or seek new employment while their renewal applications proceeded. That policy change was temporary, and auto-extensions for applicants filing after October 26, 2023 have reverted to 180 days. It remains to be seen whether the reversion means thousands of immigrants lose work authorization every month, or if USCIS can process renewal applications on time. Processing times vary based on type of applicant, but as of this writing, the agency was taking 16 months (more than 480 days) to process renewal work permit applications for asylum seekers. USCIS has indicated it is considering increasing auto-extension lengths again, if necessary.

A Belated Move into the Digital Age

In addition to making accommodations for the many people stuck in limbo, U.S. immigration agencies were forced by the pandemic into accelerating a long-overdue technological transformation by allowing for more online services instead of in-person interviews and paper-based applications. Although some changes have been abandoned, many seem likely to remain in place for the long run.

A Shift towards More Online Filing

The USCIS transition to online immigration forms has been painfully slow. In 2020, just ten of the dozens of USCIS forms could be filed online, and agency staff were still processing many paper applications by hand. But the digital shift is gaining momentum; as of this writing, applicants can file 17 forms online, including more common applications such as those to apply for work permits (in some categories), asylum, DACA, and TPS. However, dozens of other forms are still available only on paper, including applications for fee waivers, which are used by many low-income applicants.

Additionally, USCIS has been expanding the utility of its myUSCIS online system, allowing applicants to check the status of their case and sometimes even see case timeline predictions, update their address, and reschedule biometrics appointments, rather than filling out paperwork by hand or calling a contact center.

The online portal is also critical for applicants for humanitarian parole programs such as Uniting for Ukraine, created after vast Ukrainian displacement following Russia’s invasion. Once an application submitted by a U.S.-based sponsor is approved, the sponsored migrant enters their information into myUSCIS and awaits travel authorization. Unlike people applying for visas or refugee resettlement, Uniting for Ukraine applicants do not undergo in-person interviews and complex inadmissibility screenings, although they do receive background checks. As a result, applications can be approved within a few weeks. A similar process is in place for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans applying for an immigration parole program unveiled in late 2022 and expanded in early 2023.

The Biden administration applied this online-only process to its new family reunification parole programs for Colombians, Ecuadorians, Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans who are awaiting a family-sponsored green card. (Under these parole programs, individuals can enter the United States while awaiting final processing of their green card.) And the administration recently modified pre-existing family reunification parole programs for Cubans and Haitians, moving to a fully online model instead of asking family sponsors to complete paper applications and requiring beneficiaries to wait for in-person interviews at U.S. embassies abroad. This demand for in-person interviews had been especially problematic given disruptions to U.S. government operations in both countries due to strained U.S. diplomatic relations with Cuba and security challenges in Haiti.

And this year, USCIS opened a fully virtual center dedicated to processing certain humanitarian applications. The Humanitarian, Adjustment, Removing Conditions, and Travel Documents (HART) Service Center aims to reduce processing times for applications for waivers of certain immigration inadmissibility bars (601A waivers), among other goals. The administration plans to employ nearly 480 people for the center, which does not have a physical government office but is connected to existing USCIS facilities when needed for processing paper applications.

CBP One App

One of the more visible uses—and early missteps—of technology in immigration processing in recent years has surrounded the CBP One app. Released in 2020, the app was originally used by migrants accessing their U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) arrival record (I-94 forms) and by truck drivers scheduling cargo inspections at a U.S. port of entry. In 2021, the app was first used for migrant processing, allowing those subject to the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, also known as Remain in Mexico) to apply for permission to enter the United States. Its use was expanded in 2022 to migrants in Mexico looking for appointments at official U.S. border crossing points to request exceptions to the pandemic-era Title 42 expulsions policy. Since Title 42 ended in May 2023, asylum seekers and other migrants seeking to enter at a U.S. port of entry without prior authorization are required to use the app to request an appointment at a border post. Currently, 1,450 appointments are available each day through the app. Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan parolees also must submit biographical information through the app before U.S. arrival, as must those arriving through the family reunification parole programs described above.

At first, the app was plagued with challenges. It was only available in English and Spanish, gave error messages only in English, was riddled with glitches, would get quickly overloaded each morning, and the facial recognition feature reportedly did not work well for darker skin tones, among other issues. Over time, the functionality has improved. Haitian Creole has been added as a language and CBP has switched from a first-come, first-served system (which benefitted applicants with better internet access) to a daily drawing model that gives migrants more time to access the app each day when they are able.

Remote Hearings and Interviews

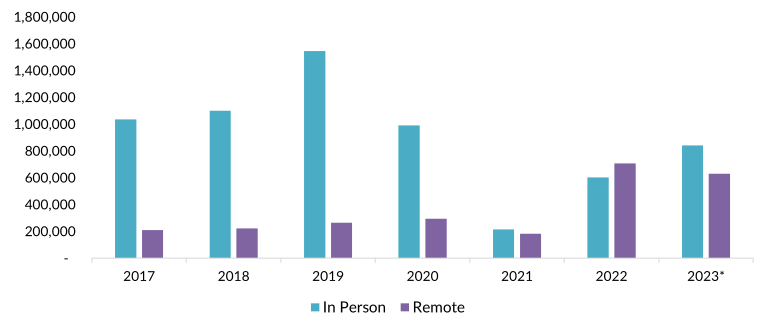

Over the past few years, immigration courts have greatly increased their use of video teleconferencing and internet-based hearings in which applicants, lawyers, and judges are not all together in a physical immigration court. In FY 2019, immigration courts conducted 264,000 remote hearings (including telephonic hearings), a number that more than doubled to 707,000 in FY 2022 and stood at 629,000 in the first nine months of FY 2023. Remote hearings can benefit noncitizens who live far from immigration courts or who wish to hire a lawyer living far from the court.

Figure 1. Hearings in U.S Immigration Courts, by Type, FY 2017-23*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 are for the first nine months of the year.

Source: Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), “Adjudication Statistics: Hearings Adjournments by Medium and Fiscal Year,” July 13, 2023, available online.

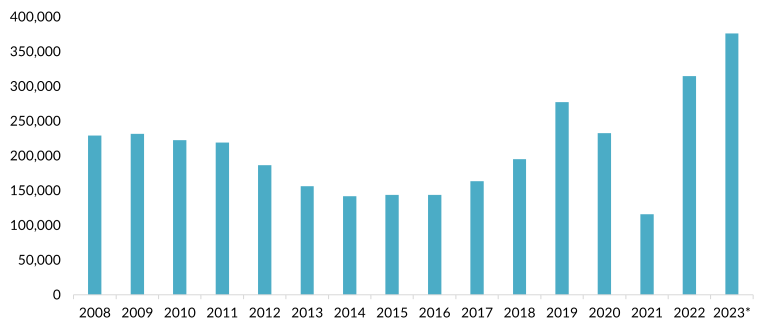

Use of remote hearings, along with increased closure of low-priority cases, may have contributed to increased court efficiency. A record 314,000 cases were completed in FY 2022 and 376,000 in the first nine months of FY 2023 (see Figure 2). However, some immigrant-rights advocates have expressed concerns that video feeds fail to properly convey nonverbal signals, tone, and other nuanced cues, and that remote hearings are not appropriate for vulnerable populations such as children and people with disabilities, or those with limited access to technology or limited familiarity.

Figure 2. Cases Completed in U.S. Immigration Courts by Year, FY 2008-23*

* FY 2023 data are for the first nine months of the year.

Source: EOIR, “Adjudication Statistics: New Cases and Total Completions,” July 13, 2023, available online.

Remote processes have also been used for resettling refugees from abroad. The Biden administration has sought to rebuild resettlement in part by using remote interviews with refugees to supplement those occurring in person. This option was particularly helpful during COVID-19 public health restrictions and travel constraints. For remote interviews, refugees have to be at a U.S. government facility, where their identity is verified, but USCIS refugee officers conduct the interview from elsewhere. Remote interviews were conducted with refugees in 17 countries in the first nine months of FY 2023. While remote interviews may not necessarily be more efficient, they allow the agency to reach individuals in places with few other refugees or where it is difficult to send refugee officers.

Government-Provided Interpreters at USCIS Asylum Interviews

People applying for asylum from within the United States and not in removal proceedings can submit their applications to USCIS, a process involving an in-person interview with an asylum officer. (Those applying defensively in removal proceedings have their cases adjudicated by the immigration courts.) Previously, asylum applicants not fluent in English were required to provide their own interpreter, but starting in September 2020 they were instead required to use government-provided telephonic interpreters. This move saved asylum seekers the trouble—and often cost—of providing their own interpreter, and ensured that people needing interpretation received it. However, it also made migrants dependent on the government to find an interpreter who spoke their language and dialect.

This policy ended in September. Asylum applicants now must once again bring their own interpreter, at their own expense, to their USCIS interview, creating challenges for those who do not know someone who can interpret for them or who are unable to hire a professional. However, USCIS has indicated that based on feedback from advocates and others it may be open to reinstating government-provided interpreters.

Has the Digital Age Come at Last?

U.S. immigration agencies’ adoption of flexible policies and belated embrace of technology and distributed work came in response to long-standing inefficiencies, the demand for social distancing, and enormous processing backlogs. The flexibilities have resulted in gains for U.S. employers, U.S. citizens and green-card holders seeking to reunite with loved ones, foreign-born workers, visitors, and individuals seeking humanitarian protections.

The overdue recalibration holds promise for greater efficiency in the future. Technological changes have made some USCIS applications and communication much simpler and introduced speedier processing. Partly through use of remote hearings, immigration courts have hit new highs in case completions. And the State Department has been able to better allocate its visa processing workload around the world. Many applicants prefer online processes, especially as internet forms and video chats have become the norm in other parts of their lives. But defaulting to internet-based operations can disadvantage people with less digital literacy, limited access to technology, or facing other barriers.

Meanwhile, the recent expiration of some pandemic-era flexibilities—and the likelihood that more will end in coming weeks—shows that improvements can be reversed and lessons of the past few years may be forgotten. USCIS has indicated it is open to restoring these flexibilities if needed. If it does, and if the State Department does the same, the enhancements that grew out of the COVID-19 crisis would not have been wasted.

Sources:

Anderson, Stuart. 2022. State Department Defends Visa Wait Times. Forbes, November 18, 2022. Available online.

Kreighbaum, Andrew. 2023. H-1B Worker Domestic Visa Renewal Pilot to Start in January. Bloomberg Law, November 28, 2023. Available online.

Monyak, Suzanne. 2021. Limited Operations at US Consulates Keep Visa Holders on Edge. Roll Call, December 22, 2021. Available online.

Neufeld, Jeremy, Amy Nice, and Divyansh Kaushik. 2023. Visa Interview Waivers after COVID. Washington, DC: Institute for Progress. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2023. Outcomes of Immigration Court Proceedings. Updated September 2023. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2022. Fiscal Year 2022 Progress Report. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.

---. 2023. Automatic Employment Authorization Document (EAD) Extension. Updated October 18, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Certain Renewal Applicants for Employment Authorization to Receive Automatic 180 Day Extension. Press release, October 27, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Employment Authorization Document Validity Period for Certain Categories. Policy Alert, PA-2023-27, September 27, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Temporary Final Rule: Asylum Interview Interpreter Requirement Modification Due to COVID-19. March 15, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. USCIS Announces End of COVID-Related Flexibilities. Press release, March 23, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. USCIS Customer Experience Online Tools, National Stakeholder Engagement. USCIS webinar presentation, October 31, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. Check Case Processing Times. Accessed November 16, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. USCIS Opens the Humanitarian, Adjustment, Removing Conditions and Travel Documents (HART) Service Center. Accessed November 16, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2022. Temporary Increase of the Automatic Extension Period of Employment Authorization and Documentation for Certain Renewal Applicants. Federal Register 87, no. 86 (May 4, 2022): 26614-26652. Available online.

---. 2023. Fact Sheet: CBP One Facilitated Over 170,000 Appointments in Six Months, and Continues to be a Safe, Orderly, and Humane Tool for Border Management. Press release, August 3, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Embassy and Consulates in India. 2023. U.S. Mission to India Surpasses One Million Visas Processed in 2023, Indians Made Over 1 in 10 Visa Applications Worldwide. September 28, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Justice Department, Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). 2023. Adjudication Statistics: Hearings Adjournments by Medium and Fiscal Year. July 13, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Adjudication Statistics: New Cases and Total Completions. July 13, 2023. Available online.

U.S. State Department. 2021. Expanded Interview Waivers for Certain Nonimmigrant Visa Applicants. Press release, December 23, 2021. Available online.

---. 2022. Addressing U.S. Visitor Visa Wait Times. Press release, November 17, 2022. Available online.

U.S. State Department, Bureau of Consular Affairs. 2022. Important Announcement on Waivers of the Interview Requirement for Certain Nonimmigrant Visas. Updated December 23, 2022. Available online.