You are here

Changing U.S. Policy and Safe-Third Country “Loophole” Drive Irregular Migration to Canada

Asylum seekers cross the U.S.-Canada border at Roxham Road. (Photo: Daniel Case)

Nearly 50,000 asylum seekers entered Canada irregularly via land crossing from the United States over a two-year period beginning in spring 2017—contributing to a doubling in the overall number of asylum requests seen in 2016. Most make their way into Canada via Roxham Road, an unofficial crossing at an otherwise unremarkable country road along the New York-Quebec border.

The surge in asylum filings is the result of a few factors, perhaps most notably U.S. policy changes that have made the United States less hospitable and growing recognition of a “loophole” in the 2004 Canada-U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA). While the treaty was designed to manage asylum-seeker processing by requiring individuals to apply for protection in the first of the two countries entered, it allows those who reside in or transit through the United States to claim asylum in Canada if they enter between official ports of entry.

Box 1. Methodology

This article presents findings from semi-structured interviews with 290 asylum seekers from more than 50 countries, with a representative sample by country of origin. They had been in Canada from a period of only a few days up to two years. Interviews were conducted from December 2018 to October 2019. They took roughly one hour, and were conducted in the respondent’s language of choice at shelters and community organizations in Toronto, Hamilton, Ottawa, and Montreal.

Recruitment took place using posters and communication through social workers and volunteers. Respondents were identified by their first name only, and offered the choice to use a pseudonym. No identifying or contact information was collected.

Interviews were also conducted with two dozen lawyers, social workers, civil servants, and personnel from government and law enforcement in Canada and the United States.

The majority doing so, according to research undertaken by the author and his research team, only briefly transited the United States before crossing into Canada. Around 60 percent of the 290 asylum claimants interviewed—from a diverse mix of countries including Haiti, Nigeria, Colombia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—had spent an average of five days before moving on to Canada. The remainder had lived in the United States for an average of six years.

The increase in asylum seekers has proven a politically and morally fraught issue for the Trudeau government in the lead-up to the October 21 federal election, offering opposition parties and civil-society groups on the right and left alike reason to criticize the centrist Liberals in power. It also has placed new scrutiny in Canada on the Safe Third County Agreement, criticized by conservatives for its role in fostering more asylum claims and on the other side of the spectrum by lawyers and refugee-rights advocates who question whether the United States remains a “safe” country.

This article, which draws from the first year of the “Understanding Emergent Irregular Migration Systems to Canada” research project, presents findings from interviews to explore asylum claimants’ motivations for claiming asylum, information sources, and experiences along their journey and after arrival. It also analyzes the effects of the recent arrivals on Canada, especially regarding the political implications. The goal is to fill a research gap by providing empirical evidence for the drivers of irregular migration to Canada.

U.S. Policy Change as a Driver of Migration to Canada

Increasing irregular arrivals to Canada may be attributed to many factors, including (mis)information spread about the STCA “loophole” through social networks and international media. Insights from interviews with asylum claimants suggest that U.S. policies are a major driver of irregular migration to Canada—though the relationship is not always linear. An increase in arrivals after change in U.S. policy is not unprecedented: discrepancies between U.S. and Canadian refugee determinations in the 1980s led to a “border rush” of predominantly Central and South American asylum seekers. The ensuing backlog in Canada’s asylum system led to the creation of the country’s Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) and motivated Canada to seek an STCA in the first place.

Causes of the Recent Uptick in Asylum Seekers

The Trump administration’s decision not to extend a long-standing Temporary Protected Status (TPS) designation for some 46,000 Haitians was the catalyst for the drastic increase in asylum claims in Canada in 2017. In April 2017, just 140 Haitians crossed into Canada at Roxham Road. The following month, the number increased to 1,355, and to 3,505 that June. Roughly half of the 6,500 Haitians who arrived during the April 2017 – June 2019 period examined, were U.S. residents, with the rest arriving from Haiti and third countries, particularly Brazil. Thus an announced U.S. policy change resulted in roughly 7.5 percent of all Haitians in the United States with TPS choosing Canada rather than risking deportation, moving to a third country, or remaining unauthorized in the United States.

Figure 1. Number of Asylum Seeker Claims on Roxham Road, April 2017-June 2019

Source: Data provided to the author by Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) under a memorandum of understanding.

A commensurate number of TPS recipients from countries other than Haiti have not sought asylum in Canada, even as the Trump administration has also moved to end designations for Salvadorans, Hondurans, Nicaraguans, and others. The lack of similar movement may owe to a number of factors, including the fact that U.S. courts have at least temporarily blocked the upcoming terminations. Obama-era Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials, advocates, and asylum seekers interviewed also noted that Latino immigrants are more politically organized and committed to resisting Trump administration policies.

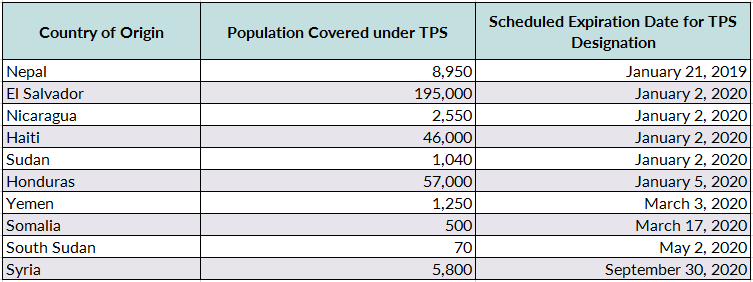

Still, more than 300,000 people risk losing TPS in early 2020, and in an environment of hostility toward asylum seekers and unauthorized immigrants, more may aim to cross irregularly into Canada, particularly if it appears the courts will not continue being a brake on Trump administration immigration actions.

Table 1. Temporary Protected Status (TPS) Populations in the United States and Expiry Dates

Note: A grant of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) provides recipients protection from removal from the United States, as well as work authorization.

Source: D’Vera Cohn, Jeffrey S. Passel, and Kristen Bialik, “Many Immigrants with Temporary Protected Status Face Uncertain Future in U.S.” Pew Research Center FactTank blog, March 8, 2019, available online.

Beyond the initial rush of Haitians in mid-2017, many others have made the journey after being in the United States for only a short period of time. Roughly 60 percent of respondents used the United States only as a transit state, spending an average of five days. They learned of the crossing from a range of sources, often through social media, YouTube, or word of mouth. Some early respondents, mostly from Nigeria, were reticent to admit that they had planned to come to Canada, and said they had no knowledge of Roxham Road before arriving in the United States. These respondents also offered similar, almost verbatim reasons for asylum. The researchers thus revised their interview structure to focus on the source of information for the Roxham Road route. Several described purchasing asylum narratives from “story sellers” or “travel agents,” typically based on persecution for gender and sexual orientation. While these types of claims are long-standing, narratives also included Donald Trump’s anti-migrant pronouncements and the specter of family separation as the reason for spontaneous transit to Canada. Thus, decisionmakers in Canada must now contend with U.S. policy in assessing claims.

However, most respondents planned to use Roxham Road from the outset. “My husband had Canada in mind for years. He wanted to do it legally, like fill out the forms online. But once he heard about Roxham Road he decided to send us,” said Hadiza, a 39-year-old woman from Niger. “It was a difficult decision. It was me and three kids. My husband had to stay behind. He sent us first and maybe he can come later.”

For these migrants, the unlikelihood of protection contributed to their choice not to remain in the United States. Roughly 20 percent had been denied visitor or skilled immigrant visas to Canada but were able to obtain or already had U.S. visitor visas. Several, predominantly from the DRC, Angola, and Pakistan, said they obtained visas by bribing U.S. consular officials. Restrictive U.S. asylum procedures, more open visa regimes, and corruption thus impact asylum claims in Canada.

Roughly 40 percent of respondents had resided in the United States for a period of years, mostly unauthorized residents who had overstayed a visa or received a negative asylum decision. Unlike many who transited through the United States in days, this group explicitly stated that their reasons were directly tied to U.S. policies.

“This word ‘illegal’ is weird to me, even if I use it about myself,” said Derrick, a 22-year-old from Gabon. “Every day people tell you to go back to your country, that if you’re struggling you should just go. That’s not a life. I’m not a criminal, I don’t hurt people. I just want to work and study.”

Among respondents’ fears were the threat of workplace immigration enforcement operations or law enforcement status checks. The most common catalysts for the decision to use Roxham Road were that a relative or community member had been incarcerated or deported, or that they were running out of funds or appeals in lengthy U.S. asylum procedures. Several said they abandoned claims because of a 2018 policy to schedule new cases in immigration court before older ones, a “last in, first out” policy DHS implemented to deal with the rapidly rising Central American caseload. Regardless, most reported a growing fear from the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant discourse, more frequent discrimination, and anxiety about the fate of their children should they be apprehended. Finally, around 3,500 U.S. citizens had crossed the border during the April 2017-June 2019 period, according to Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), signaling the displacement of mixed-status households with unauthorized immigrant parents and U.S.-citizen children.

Many who arrived in late 2018 or in 2019 had actively researched Roxham Road, which had garnered significant media attention in 2017, often through online searches and conversations with community members, but considered it a last resort. Interview questions asked respondents who resided long term in the United States where Canada ranked among options including return to their country of origin, relocation to a third country, or move elsewhere in the United States, particularly a sanctuary jurisdiction. Most were incredulous about the notion of returning to their country of origin, but would have preferred to remain in the United States were it not for the Trump administration. Canada offered the simplest and safest option.

Transnational Border Crossers

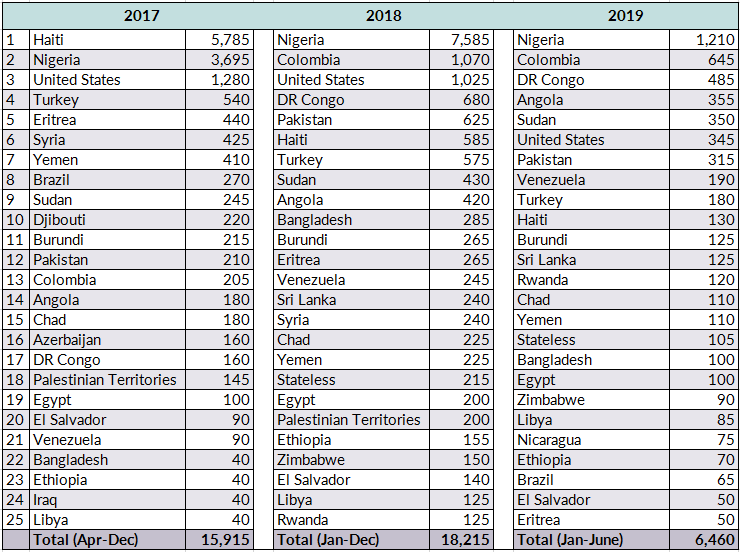

Irregular migration to Canada rapidly became more transnational after receiving attention from mainstream and social media. By late 2017, Nigeria overtook Haiti as the top country of origin, and the number of nationalities diversified significantly.

Table 2. Top 20 Countries of Origin of Roxham Road Asylum Claimants, April 2017- June 2019

Source: IRCC data provided to the author under a memorandum of understanding.

For most who transited the United States over a short period of days, the decision to seek asylum in Canada has less to do with U.S. policy and more to do with finding a solution for a precarious situation. To take one example, many claimants who are considered Yemeni, Palestinian, or Sudanese in official data were born and lived in Saudi Arabia. “Saudi-ization” policies—aimed at increasing the share of native-born Saudis in the workforce—resulted in the termination of these workers’ residence permits. For Yemenis, this means risk of deportation to a country with which they have no connection and one experiencing a humanitarian emergency. Many Palestinians would be rendered stateless. Respondents coming from these types of situations relayed how their social networks were abuzz about the U.S. route to Canada as early as May 2017, offering a new means to fulfill pre-existing desires for mobility.

While those with financial means often fly to the United States, an increasing number, predominantly from Africa, undertook multimonth and even multiyear overland journeys from Brazil, through Central America, to the United States. This comports with global findings that the first people in irregular migration systems are often those with the capital to move quickly, while those with fewer resources take more precarious routes.

The less well-heeled or those unable to secure U.S. visitor visas recounted harrowing danger, including violence and extortion by state security services, criminals, and smugglers; capsized boats on the coast of Colombia; horrific experiences in the Darien Gap jungle in Panama; predation from gangs in Mexico; and waiting in dangerous conditions at the U.S. border. “The jungle in Panama was very, very hard. You’re walking past dead bodies. You spend ten days or two weeks. You have to walk through rivers, over mountains. There are snakes and bandits… You walk for days, from the time the sun comes up until it goes down, and you sleep wherever you lay,” said Naomi, a 22-year-old from Angola. “If a child dies, the parent leaves it behind. If your husband dies, you leave them behind. Because if not, it’s you who will be left behind. It was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done.”

(Mis)Information and Social Networks

Social networks play a strong role in would-be migrants’ decision-making. In the case of Nigerian claimants, for example, Pentecostal churches play a key role planning travel and social connections once in Canada. Refugee claimants from Yemen, Colombia, and a range of African states receive detailed instructions from community members who have already arrived. Some respondents said U.S. aid organizations encourage people to move on to Canada after release from detention.

As in other irregular migration corridors, misinformation and rumors seem to have a strong influence. Whispers of impending enforcement actions in the United States served as a catalyst for several respondents. More often, rumors are spurred by minority-language media and are amplified and distorted through social media. These often have some basis in fact. Recent arrivals reported rumors that the Canadian border will be closed if the Conservatives win the October election, spurring people to hurry on their journeys.

When Trump announced a ban on refugees from certain Muslim-majority countries within days of taking office Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted: “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada.” A number of respondents cited this juxtaposition as a prominent example that Canada was “saving” refugees from the United States. “I was hearing a lot of things about the Prime Minister of Canada. My friend told me they’re welcoming people there. And I thought ‘this is the place I’m supposed to go’,” said Bilal, 25, from Yemen.

It would be disingenuous, however, to claim a tweet was the direct catalyst for migration. The irregular movements to Canada instead owed in a broader sense to the erosion of protection and retreat from norms of asylum in the United States, against which people measured their chances in Canada.

Interviews illustrate that claimants had accurate information about the route, yet little knowledge of the asylum process in Canada. Respondents were surprised by the scale of the flow, wait times for hearings, not immediately receiving housing, and the difficulties in finding child care and work. And while only a few respondents said they would have made a different decision, interviews and DHS data suggest that over the past two years dozens or hundreds of asylum seekers had either returned to their country of origin or used smugglers to re-enter the United States.

A Surprising Lack of Criminality at the Border

In comparison to other irregular migration corridors—and indeed on other legs of the journey—there is remarkably little criminality at the U.S.-Canada border. The route existed long before Roxham Road made headlines. It generally consists of transit by bus or private car to Plattsburgh, New York, and taxi companies transporting people to the border. Individuals with large families or health issues, or those who fear interactions with U.S. immigration enforcement, use a network of private drivers. None of this activity amounts to smuggling under U.S. or Canadian law, and there is very little evidence of abuse while people move within the United States.

A small number reported intimidation by taxi drivers in Plattsburgh. In the early days, taxi companies overcharged for the 25-mile drive to Roxham Road. In May 2019, the New York attorney general convicted the owner of one company of systematically overcharging. This trend has abated, and most respondents relayed either no meaningful interactions or acts of kindness from drivers, who calm agitated people and explain the process at the border.

The most significant exploitation is in Canada, particularly by immigration consultants and lawyers. In several cases—in collaboration with agents in the United States—consultants from migrants’ national or linguistic community convinced individuals to come to Canada. Such consultants offer a “full-service” fee, including transportation to the border, access to a safe house in Canada (which is unnecessary), and promises to circumvent Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) wait times (which is not possible). They then extract as much money as possible before abandoning claimants. Other respondents, primarily from Latin America, have reported lawyers charging exorbitant rates for paperwork that could be covered by legal aid organizations. As Nadya, a 35-year-old woman from Colombia, explained: “The agent charged us $1,500, and put us in touch with a lawyer in Canada, [who] said it was $6,000, then $1,500 each to get a work permit. He said could get us work and we could pay him back. Once we got to Montreal there was a group of Latino lawyers, [who] explained we would get free legal aid. We asked, ‘How much do we have to pay [for] a work permit?’ It’s then we realized he was trying to take advantage of us.” Finally, there is some evidence that Mexican and Nigerian claimants arrive owing debts for passage and are immediately recruited to work under the table for temporary labor agencies.

These types of exploitation pale in comparison to the abuse and danger reported along irregular migration routes elsewhere around the globe. Most interviewees reported positive experiences with Canadian officials and consider the system fair despite long wait times. Understood in a global context, claiming asylum in Canada remains a safe process.

Impacts on Canada

The backlog at Canada’s IRB, a tribunal that hears refugee claims, had grown to more than 79,000 cases as of August 2019, with average wait time of two years for first hearings. A 2019 auditor general’s report found that wait times could increase to five years by 2024 if the number of claims remains constant. The increase has strained shelter capacity in major cities, particularly Montreal and Toronto. Polling by the Angus Reid Institute suggests that while most Canadians remain in favor of welcoming refugees and asylum seekers, they overestimate the number of refugees present, see irregular migration as a crisis, and those entering at Roxham Road as “queue jumpers” or “bogus refugees.” Attacks on shelters and demonstrations against housing asylum seekers in Toronto, and far-right protests at shelters in Montreal and on the border in Lacolle, Quebec have occurred.

The opposition Conservative Party of Canada has accused the government of losing control of the border. In late 2018, the party took a page from the playbook of Europe’s far-right populists, claiming the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration would mean ceding sovereignty to the United Nations. The Ontario Progressive Conservative Party refused to cooperate with the federal government over shelters and housing for asylum seekers, and made the unprecedented move of canceling legal aid for refugee claimants, which is a crucial part of the asylum process. The goal was to foster chaos in the lead-up to the election and shift the burden to Quebec, a crucial electoral battleground.

It has also been expensive. After lobbying from the legal and advocacy community, the federal government announced CAD $26.8 million in funding to address the legal aid shortfall. The 2018 budget allocated $72 million for capacity-building at IRB, and the 2019 budget an additional $1.2 billion over five years. Providing shelter space for asylum seekers has cost cities somewhere in the range of $150 million. The political challenge is that effective policy requires administrative solutions, while critics can mobilize narratives of economic migrants gaming the asylum system as a result of uncontrolled borders.

The government has sought to balance capacity building with restrictive policies. In 2018 it created a new Minister of Border Security and Organized Crime Reduction, appointing a tough-on-crime ex-police chief from Toronto. It also changed the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act to prevent asylum shopping by denying access for people who previously sought protection in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, or the United Kingdom. The change was roundly criticized by refugee-rights advocates and has caused significant uncertainty for both asylum seekers and the legal community. Officials interviewed on the condition of anonymity confirmed it is a pre-emptive measure in case of U.S. policies that might spur more migration, particularly in the lead-up to the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

Loophole or Safety Valve?

Much of the asylum debate in Canada has been about closing the STCA “loophole.” The left-leaning New Democratic Party and many academics, lawyers, and refugee advocates have called for Canada to suspend the accord, on grounds the United States is no longer a safe country for asylum seekers. Amnesty International and the Canadian Council for Refugees are challenging its constitutionality. The Conservative Party has taken the opposite position, promising to extend the agreement to what has been long heralded as the “world’s longest undefended border.”

Applying the agreement between ports of entry would require vast new funding for federal police, who would be tasked with apprehending and detaining thousands of people. The result would create more criminalized smuggling markets, make migrants vulnerable to trafficking, create precarious undocumented populations, and push people to more dangerous routes. It would also fundamentally damage Canada’s global identity.

On the other hand, suspending the Safe Third Country Agreement would likely result in more asylum claimants, given peoples’ decisions have been significantly affected by ever-more hardline U.S. policies and rumors of more open Canadian ones. Those arriving at regular ports of entry would still increase IRB backlogs. And the move would likely backfire politically, with voters potentially rewarding anti-refugee political platforms, as in Europe and the United States.

Restrictive policies are unlikely to stem the flow of people, and Canada has no leverage in negotiations with the White House over the STCA. Likewise, unilaterally suspending participation in the accord risks riling the U.S. government at a time when the Trump administration is limiting access to asylum and attempting to compel other states to take on the responsibility for hosting refugees.

While perhaps counterintuitive, the status quo with regards to the Safe Third County Agreement is a viable option. Roxham Road is well managed. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) conduct routinized security screening and first-line admissibility checks. The majority of interviewees took pains to mention they were treated humanely, in sharp contrast to experiences at other borders. Volunteers who monitor the crossing relayed that while there were instances of intimidating behavior by the RCMP in 2017, they are now rare because of the standardization of procedures, permanent infrastructure, and observation by volunteers. People arrive safely, and without criminal networks.

While politically fraught in the current context, Canada receives a small number of asylum seekers in comparison to other refugee-receiving countries. It has an established and well-funded settlement sector, and refugee-status determination procedures are largely fair. Staying the course until the 2020 U.S. elections would allow for capacity-building and long-term planning that bucks the global trend of reactionary policies in liberal democracies.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a research project, “Understanding Emergent Irregular Migration Systems to Canada,” funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and hosted by the Centre for Refugee Studies at York University and the Global Migration Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto.

Sources

Angus Reid Institute. 2019. “Immigration: Half Back Current Targets, but Colossal Misperceptions, Pushback over Refugees, Cloud Debate,” 17 October, 2017. Available Online.

Bergeron, Claire. 2014. Temporary Protected Status after 25 Years: Addressing the Challenge of Long-Term “Temporary” Residents and Strengthening a Centerpiece of U.S. Humanitarian Protection. Journal of Migration and Human Security 2 (1): 22-43.

Castles, Frank. 2004. Why Migration Policies Fail. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 27 (2): 205-27.

Cohn, D’Vera, Jeffrey S. Passel, and Kristen Bialik. 2019. Many Immigrants with Temporary Protected Status Face Uncertain Future in U.S. Pew Research Center FactTank blog, March 8, 2019. Available online.

Collyer, Michael. 2010. Stranded Migrants and the Fragmented Journey. Journal of Refugee Studies 23 (3): 273-93.

Cowger, Sela. 2017. Uptick in Norther Border Crossings Places Canada-U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement under Pressure. Migration Information Source, April 26, 2017. Available online.

Elash, Anita, Diana Swain, Tara Carmen. 2017. “Similarities in Nigerian Asylum Claims based on Seual Orientation have Legal Aid Ontario Asking Questions,” CBC News. 8 Nov, 2017. Available online.

Forrest, Maura. 2019. Asylum Backlog Will Likely Reach 100,000 by End of 2021, IRB Head Tells MPs. National Post, May 28, 2019. Available online.

Garcia, Maria Christina. 2006. Canada: A Northern Refuge for Central Americans. Migration Information Source, April 1, 2006. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM), Global Migration Data Analysis Center. 2017. Measuring Global Migration Potential, 2010-15. Data Briefing Series, Issue 9, IOM Global Migration Data Analysis Center, Berlin, July 2017. Available online.

Lapierre, Matthew and Jeff Gray. 2019. “Ottawa Announces Immigration, Refugee Legal Aid Funding for Ontario, Slamming Ford Cuts”. The Globe and Mail, August 12, 2019. Available online.

Menjívar, Cecilia. 2017. Temporary Protected Status in the United States: The Experiences of Honduran and Salvadoran Immigrants. Center for Migration Research, the University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, May 2017. Available online.

Passel, Jeffrey S. and D’Vera Cohn. 2009. A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. Available online.

Watson, Ben. 2019. Local Taxi Owner Pleads Guilty to Overcharging Refugees. Press-Republican, May 9, 2019. Available online.