You are here

The Impact of Mexican Maternal Migration on Children’s Future Ambitions

Of the children surveyed in Puebla, Mexico, girls were more likely than boys to express a desire to continue their schooling, regardless of parental migration status. (Photo: Curt Carnemark/World Bank)

Most of the research on migration from Mexico to the United States, which has long represented the world’s largest migration corridor, has been about why people migrate, what their lives are like in the host country, and the U.S. policies and conditions in Mexico that shape these flows. Though Mexican women comprise a significant share of the flow, there has been less focus specifically on their movement and the effects of their departure on those left behind.

Historically, Mexican migration has been predominantly male, especially among the unauthorized. There has been a dramatic increase in the number of Mexican women in the United States over the past few decades, however, amid rising overall migration during the 1990s and early 2000s and as the female share of Mexican migration has ticked up. While men still represent the majority of Mexican immigrants to the United States, accounting for 52.6 percent in 2014, that share is down from 55.4 percent in 2000.

In recent years, Mexican women have been more likely to migrate alone, leaving behind children in the care of relatives or friends. While family separation among Mexican migrant households is typical of the cross-border experience, it is now likely to be between mothers and children. These periods of separation are also more likely to be of longer duration. The hardening of the U.S.-Mexico border and the increasing risks and costs of migration hinder the abilities of migrants to regularly exit and re-enter the United States.

As more women migrate, there are potential educational consequences for their children left in Mexico with substitute caregivers. This article explores the impact of rising numbers of female Mexican migrants on the educational experiences and aspirations of the children left behind. The article is informed by survey data from a study of school children in Puebla, Mexico.

Female Mobility and Transnational Motherhood

The term “feminization of migration” was coined to point to the increased movement of women migrating independently to look for jobs rather than to reunite with their husbands. Often moving from poor to industrialized countries to work in low-skilled jobs, many women—as the principal wage earners for their families—are driven to migrate in search of a living wage, leaving their families and children behind. Worldwide, women comprised 52 percent of the international migrant stock in advanced industrialized countries in 2015, up from 51 percent from 1990, the United Nations reports.

The rising number of female migrants has prompted interest in “transnational motherhood,” a term first used by Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo and Ernestine Avila in 1997 to describe the practice of mothers living and working in different countries from those of their children, thus resulting in a “care deficit” in many nations in the global south.

Mexican migration to the United States exemplifies the trend of growing numbers of women moving internationally. The female Mexican immigrant population in the United States grew from 1.9 million in 1980 to 5.6 million in 2014, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates. A 2006 report from the Confederación Nacional Campesina (CNC) in Mexico reported that rural women comprised 20 percent of all Mexicans crossing the border into the United States, up from 5 percent during the 1980s.

Many of these migrants are parents who have left their children behind. In a 2005 survey of Mexican immigrants at Mexican consulates throughout the United States, researchers found that 18 percent had at least one child between the ages of 0 and 18 still living in Mexico. Another study found that of all Mexican immigrants in the United States, 38 percent of men and 15 percent of women had a son or daughter living in Mexico.

With about half of all Mexican immigrants living in the United States without authorization, illegal migration has been, and continues to be, a complex issue of enormous sociopolitical and economic consequence for Mexican women who migrate to the United States. It also holds deep consequences for the ability of these families to see each other occasionally or reunite more permanently, as long-held patterns of circularity seen in earlier migration waves have been disrupted by the major increases in enforcement manpower and resources at the U.S.-Mexico border since the mid-1990s.

In Focus: Educational Aspirations of Children in Puebla

Isolating the impact of maternal migration on the future ambitions of children left behind is difficult in a country with such long-standing migration ties to the United States. To determine how maternal migration affects school experience and the educational aspirations of boys and girls in Mexico, the author conducted surveys with 225 children between the ages of 7 and 16 in four schools in the Tlapanalá municipality in the state of Puebla. The surveys were conducted in three secundarias, or junior high schools (185 students) and one primaria, or elementary school (40 students) in June 2012.

The two factors used to examine educational experience were homework completion and desire to continue studying in the future. During extensive ethnographic research in Puebla, the author found that parental migration influenced the educational aspirations of youth in a gendered manner. Even though both boys and girls reported experiencing feelings of resentment and love for their absent mothers, they responded differently when the issue at stake was academic performance and schooling experiences.

The data presented here represent a small slice of a larger multisite ethnographic study that sought to follow the people in communities with high rates of migration in Puebla state.

Findings on Parental Migration

Of the children surveyed, 58 percent (131) were female. An overwhelming majority (93 percent) of participants reported having at least one family member living in the United States—with 33 percent saying one or more parents were U.S. residents.

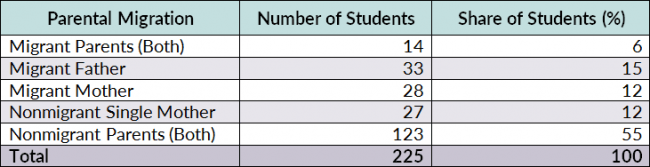

In a region such as Puebla with long-standing ties to the United States, male migration has long been the norm. History and geography have contributed to this flow: from building railroads to harvesting crops under the Bracero guestworker program, Mexican men have been working in the United States for more than a century. In recent years, however, women have begun following the well-worn migration corridor between Puebla and the United States. Thus, while most participants who reported having a parent living in the United States had a migrant father, 18 percent reported a mother who had migrated within the past decade (see Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of Parental Migration among Students Surveyed in Tlapanalá, Mexico, 2012

Source: Author’s tabulation of children’s survey responses in Tlapanalá, Puebla, Mexico.

The children reported the occupations of their parents while in Mexico as predominantly stay-at-home for the mothers (78 percent) and campesino, or farmer, for the fathers (44 percent). Survey participants reported their mothers’ occupations in the United States were the same, whereas they described their fathers as working largely in the service industry. Even though some migrant women work outside the home, many do not—often because of care-giving responsibilities in the home and limited English proficiency or access to transportation. The increased migration of women brings to the forefront a potential change in established gender roles; however, this research instead reveals a struggle between ideologies. To say that women become “empowered” through the process of migration because of a new breadwinner status that some experience is to disregard the constant internal tug-of-war they face about what a good mother and a good woman “should” be. At the same time, to state that women only reproduce the gender roles present in the host society is to ignore the active and creative ways in which mothers engage in their roles between these two extremes.

Findings on Educational Experience

Research over the last three decades has shown a correlation between time children spend completing homework and a positive experience with learning and schooling. Other studies on youth with immigrant parents have looked at academic performance through grades and interviews about aspirations to understand their future plans. An earlier study in which the author observed children in 2nd-grade and 10th-grade classrooms in Mexico found that children were motivated to finish homework in order to participate in class activities. Homework completion also reflects in part how much time students have at home to dedicate to school-related assignments. Of concern is not whether the homework is done correctly, but the effort and importance placed on completing the assignment. The author’s research showed that children sometimes struggled to complete homework in households where there were many people to care for or where their labor was needed for income. Thus, making time to do homework signaled an effort to do better in school. In the Tlapanalá survey responses, children who reported finishing their homework also showed aspirations to stay in school. For example, many survey respondents took pride in showing off their completed homework to the author as well as to parents who were away.

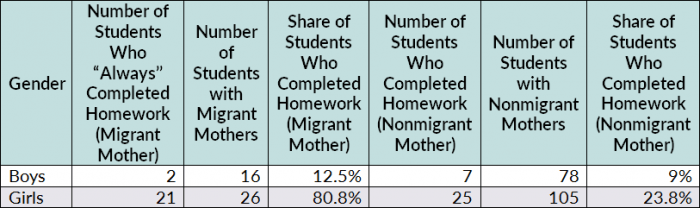

Rates of homework completion among participants with migrant mothers and fathers demonstrate a sharply gendered finding (see Table 2).

Table 2. Homework Completion by Gender and Mother’s Migration

Source: Author’s tabulation of children’s survey responses in Tlapanalá.

Eighty-one percent of girls with migrant mothers reported always doing their homework, compared to 24 percent of girls with mothers at home. The variation for boys was smaller, as they mostly reported not finishing their homework regardless of whether their mothers were migrants.

Previous studies have demonstrated a gender inequality regarding educational achievement, finding that boys generally underperform relative to girls in schools throughout the industrialized world. Some see the gender gap as largely biological in origin. Others find schools a demasculinized learning environment and with an alleged tendency to evaluate boys negatively for fitting into this environment less well than girls. Yet the true impact of school context on the size of the gender gap in academic performance remains controversial.

Girls with migrant mothers in Tlapanalá responded more positively about homework completion than boys with migrant mothers. The following narratives may be linked to girls’ superior educational performance: 1) educational attainment serves as a path to reunification with mothers. Girls did well in school in order to live up to their mothers’ expectations and with the hope that their mothers would reward them by bringing them to the United States; 2) Girls performed well in school with the expectation of receiving material gifts; and 3) school offered a space to forget about family or personal problems.

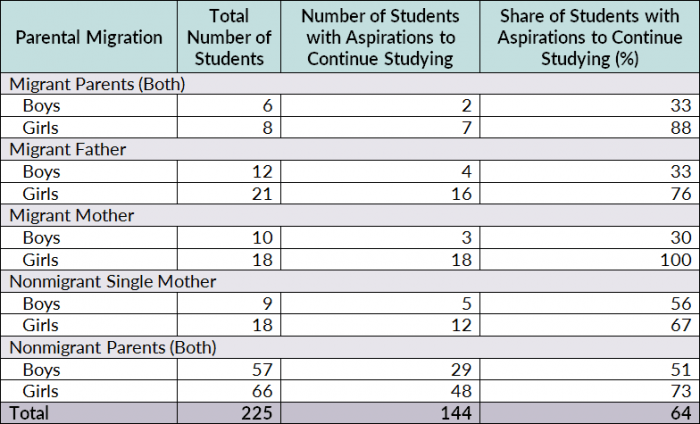

Turning to the second factor studied, future aspirations, survey participants were asked: What would you like to do after you finish secundaria? Girls were more motivated than boys to continue their studies regardless of having a migrant mother, but the level was even higher when mothers had migrated. All the girls with an absent mother and 96 percent of girls with either a migrant mother or two migrant parents planned to continue their studies, compared to 72 percent of girls with mothers at home (see Table 3).

Table 3. Student Aspirations to Continue Studying by Gender and Parental Migration

Source: Author’s tabulation of children’s survey responses in Tlapanalá.

On the other hand, 30 percent of boys with a migrant mother planned to continue studying, compared to 56 percent with a mother at home—showing that maternal migration may influence their aspirations. This finding is consistent with other studies in Mexico that describe children of migrant parents, particularly boys, as having a greater propensity to drop out of school than their peers with parents at home. Traditionally, male migration has dominated the U.S.-bound flow from Mexico, thus men and young male adults may be more inclined to migrate than their female counterparts. The normalized idea of male migration may influence boys to leave school in order to migrate.

Division of Labor in the Home

In addition to homework and educational aspirations, the survey reviewed responsibility for household duties. This section focuses on respondents in junior high school. The chores included in the survey were: cooking, cleaning, taking care of siblings, feeding the family, helping with homework, and feeding the animals.

In a follow-up survey of migrant mothers from Puebla now living in New York, mothers expressed a desire for their daughters to excel both to justify why they left Mexico and so their daughters could experience a life that they themselves did not have. These expectations, however, did not change the fact that gender roles were asserted within the household and that female-led migration actually had the effect of overburdening girls with household labor. Though girls were more affected than boys by the absence of their mothers in having to do housework, they still outperformed boys at school.

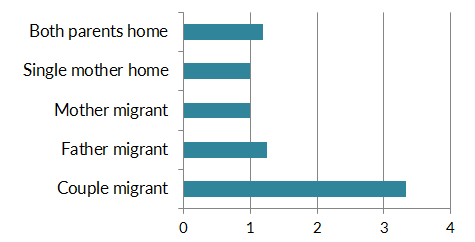

The housework of male respondents increased significantly only when both parents were gone (see Figure 1). Girls, on the other hand, had a significant increase when the mother was the one gone, as they took over many of the responsibilities of the mother.

More than half of girls (56 percent) reported cleaning the house as their primary responsibility, while 48 percent of boys reported feeding the animals as their primary duty. The only housework boys overwhelmingly reported not doing was cooking, reflecting the gendered division of labor. According to the survey, the average time of separation between children and parents surveyed was six years; it is therefore possible that household division of tasks and educational aspirations changed over the time of separation.

Figure 1. Number of Household Chores Accomplished by Boys, by Parental Migration

Source: Author’s tabulation of children’s survey responses in Tlapanalá, Puebla, Mexico.

Figure 2. Number of Household Chores Accomplished by Girls, by Parental Migration

Source: Author’s tabulation of children’s survey responses in Tlapanalá.

Remittances: Gifts and Money

The children were further surveyed about remittances. First, participants were asked if anyone in their family lived in the United States, followed by a question on who the family members were and how long they had been gone. The survey then asked if the students had received any gifts other than money from family members abroad and to specify which relative had sent the gifts. Finally, participants were asked which family members abroad had provided money. The results showed that migrant mothers and fathers were frequent remitters, but that material goods were more commonly sent than money.

For participants with absent mothers, 97 percent who received gifts also received money. In households with mothers present, the percentage of children receiving gifts and money dropped to 71 percent. When both parents were home, 69 percent of children reported receiving gifts and money from other relatives in the United States. In addition, when the father was a migrant, 76 percent of children receiving gifts from the United States also received money.

It is difficult to isolate the impact of remittances on educational experiences and aspirations, as 93 percent of those surveyed received gifts in the form of material things or money from a family member in the United States. The data indicate that when mothers are absent children and youth receive money and gifts at a higher rate than when they are home.

Although most studies agree that women are increasingly migrating to provide for their families, the question of how much remittances and migration help migrant families in Mexico is a matter of debate. Remittances can exacerbate economic inequalities in the migrant-sending society, according to a 2005 study by Robert Smith. Others have asserted that families with migrant members enjoy economic advantages. Mexican children with a migrant parent in the United States have better grades than children in nonmigrant households, potentially associated with an increase in overall financial resources for such families, according to 2001 research by Kandel and Kao. However, parental migration takes an emotional toll. In a separate 2001 study, depression levels were found to be higher among immigrant children in the United States who experienced separation prior to migration than those who migrated with their parents. Research in 2009 from Heyman et al found that in Mexican states with a long-standing tradition of U.S. migration, the migration of a caregiver, including the mother, was associated with academic or behavioral problems and emotional difficulties among children.

Gendered Impact of Maternal Migration

First and foremost the analysis of the surveys mentioned above demonstrated gendered results. In the same way that the gender of the migrating parent is important for the educational experiences of children, the gender of the child left behind matters: girls and boys experienced separation in different ways. The aspirations of girls to continue in school grew as their mothers migrated, while those of boys fell.

Additionally, maternal migration increases the amount of housework girls are expected to perform. Even though girls reported always completing their homework, more time spent on household chores could mean less time to do school assignments, potentially impacting academic performance. The housework responsibilities of boys did not change dramatically when mothers migrated.

Many studies have shown mothers to be more consistent remitters than fathers. Even though a higher share of mothers sent money and gifts, fathers were also consistent. The link between the gender of migrant parents, remittances, and educational experience is one that merits further study.

Though these and other factors affect children’s schooling, the results from Tlapanalá demonstrate gendered implications for transnational motherhood and the educational experiences and aspirations of the children left behind.

Editor's Note: The research presented here is drawn from the author’s PhD dissertation, aspects of which were previously published in Refugees, Immigrants, and Education in the Global South: Lives in Motion.

Sources

Confederación Nacional Campesina (CNC). N.d. Accessed October 13, 2016. Available online.

Dreby, Joanna. 2010. Divided by Borders: Mexican Migrants and Their Children. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Garcia-Zamora, Rodolfo. 2006. “Un pasico: Mujeres y niños en comunidades de alta migración internacional en Michoacán, Jalisco y Zacatecas, México.” In Las remesas de los migrantes Mexicanos en Estados Unidos y su impacto sobre las condiciones de vida de los infantes en México. Unpublished UNESCO field report, 2006.

Heymann, Jody, Francisco Flores-Macias, Jeffrey A. Hayes, Malinda Kennedy, Claudia Lahaie, and Alison Earle. 2009. The Impact of Migration on the Well-being of Transnational Families: New Data from Sending Communities in Mexico. Community, Work & Family 12 (1): 91–103.

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierette and Ernestine Avila. 1997. I’m Here, but I’m There: The Meanings of Latina Transnational Motherhood. Gender & Society 11 (5): 548-60.

Kandel, William and Grace Kao. 2001. The Impact of Temporary Labor Migration on Mexican Children’s Educational Aspirations and Performance. International Migration Review 35 (4): 1205-31.

Smith, Robert C. 2005. Mexican New York: Transnational Lives of New Immigrants. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Suárez-Orozco, Carola and Marcelo M. Suarez-Orozco. 2001. Children of Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2016. International Migration Report 2015. New York: United Nations. Available online.

Zong, Jie and Jeanne Batalova. 2016. Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source, March 17, 2016. Available online.

Zúñiga, Victor and Edmund T. Hamann. 2009. Sojourners in Mexico with U.S. School Experience: A New Taxonomy for Transnational Students. Comparative Education Review 53 (3): 329-53. Available online.