You are here

Amid Record Venezuelan Arrivals, Biden Administration Embraces Border Expulsions Policy

Venezuelan migrants at a reception center in Brazil. (Photo: Ron Przysucha/U.S. State Department)

The Biden administration’s announcement of a policy to expel to Mexico some Venezuelans arriving without authorization at the U.S.-Mexico border represents a significant reversal for a president who campaigned against similar approaches by his predecessor. The action is particularly noteworthy given the Biden team’s effort to end the Title 42 expulsions policy that the Trump administration imposed at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Biden administration’s action on arriving Venezuelans marks the first invocation of the Title 42 authority not on public-health grounds, but as an immigration enforcement measure.

By pairing the expulsions with a new, narrowly defined humanitarian parole program authorizing some Venezuelans to travel to the United States, the administration is acknowledging the challenge of rising Venezuelan migration, which reached an unprecedented 188,000 border encounters in fiscal year (FY) 2022. Record spontaneous arrivals of asylum seekers and other migrants from Venezuela and a growing number of other countries represent a glaring political liability for President Joe Biden and fellow Democrats. Republicans have seized on the issue ahead of the upcoming midterm elections, labeling it the “Biden border crisis,” with a trio of GOP governors transporting migrants from Texas and Arizona to New York, Chicago, and Washington, DC in a showy political stunt.

The Venezuelan policy highlights the administration’s uneven responses to migrants seeking humanitarian protection. The Title 42 policy was never applied consistently across nationalities and, previously, Venezuelans were rarely expelled, due to the lack of formal diplomatic relations with Venezuela.

The new parole program, available to up to 24,000 Venezuelans who have a financial sponsor in the United States and arrive via airplane, was ostensibly modelled after a recent program for Ukrainians. Yet the Venezuelan program is significantly different, most importantly in that it excludes those who arrive without authorization between U.S. land border ports of entry. The Venezuelan program is also much smaller—just one-fourth the size of the Uniting for Ukraine program.

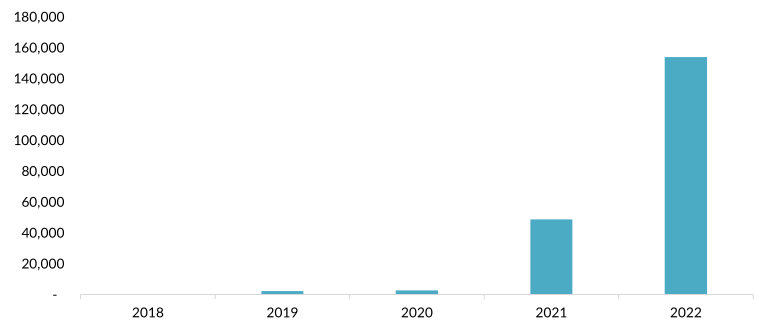

The new approach is a clear indication that the administration is encouraging Venezuelans to opt for legal migration instead of irregular routes, which typically involve a trek across the dangerous Darién Gap connecting Colombia to Panama and then through Central America. Due to ongoing political and economic instability in their country, difficult integration conditions in South American nations where most of the more than 7 million departing Venezuelans have headed since 2015, and the United States’ inability to remove many of them, Venezuelans have been arriving in increasingly rapid numbers in recent years. U.S. authorities encountered Venezuelans fewer than 100 times at the U.S.-Mexico border in FY 2018; the numbers increased to 49,000 in FY 2021 and almost 188,000 in FY 2022, with nearly 34,000 in September alone.

Figure 1. Encounters of Venezuelans at U.S.-Mexico Border, FY 2018-22

Sources: U.S. Border Patrol, “Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector,” accessed October 21, 2022, available online; U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Nationwide Encounters,” updated October 21, 2022, available online.

Unauthorized arrivals have also increased from places beyond Mexico and northern Central America, which have been the key source countries for years. For the first time ever, encounters of Cubans, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans surpassed encounters of Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans in FY 2022. In all, migrant encounters at the U.S. southern border reached an unprecedented high of 2.4 million in FY 2022. Of these, 45 percent resulted in expulsions under Title 42, which prevents individuals from being able to request asylum.

If deterrence is the goal, initial evidence suggests the new policy may be working—at least in the short term. The week after it was announced, the average daily number of Venezuelan border encounters dropped by 86 percent from the previous week, from 1,131 per day to 154. The number of migrants crossing the Darién Gap also declined by 80 percent, Biden administration officials say. It remains to be seen, however, whether this change will hold.

Recent Venezuelan arrivals are markedly different than prior waves, who have tended to be wealthier or solidly middle class, arrived with visas, and settled mostly in South Florida. In 2021, approximately 545,000 Venezuelans lived in the United States. Those arriving in recent months tend to lack connections to U.S. communities and have increasingly relied on local governments and aid groups for basic needs such as shelter, food, and health care. This has rattled policymakers in many regions, leading to calls for more federal coordination.

This article examines the Biden administration’s new approach to Venezuelan migration and how it differs from policies towards other migrants seeking humanitarian protection.

Inconsistent Positions on Title 42

The new policy on Venezuelans represents a major shift in the use of Title 42. The authority was activated by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in March 2020, and due to ongoing litigation has continued, despite Biden administration efforts in April 2022 to end it. Although ostensibly triggered by the Trump administration because of public-health concerns, the head of the agency’s division of global migration and quarantine, Martin Cetron, recently told Congress that the order was “handed” to the CDC by Trump White House officials intent on limiting immigration.

Due to strained diplomatic relations, the government has long faced obstacles expelling Cubans, Haitians, and Venezuelans to their origin country. U.S. relations with the Maduro government in Venezuela formally ended with the Trump administration’s recognition in January 2019 of opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim president. Although the Biden administration later quietly negotiated the return to Colombia of some Venezuelans holding status there, numbers were low. In total, only about 1,300 Venezuelans were expelled under Title 42 in 2021.

The U.S. government pressed Mexico to accept them, but that country faced its own constraints in returning Venezuelans. Thus, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has for the last two years allowed most Venezuelans arriving without authorization at the southern border to enter the country and placed them in immigration court proceedings, where they can apply for asylum or other forms of relief.

Per the agreement with the United States, Mexico will accept up to 1,000 Venezuelans a day, which is about as many as were arriving daily when the Venezuelan policy was implemented. Mexico, however, has strained facilities that may not be able to accommodate tens of thousands of Venezuelans, although it has tried to increase shelter and integration capacity with support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Mexico will reportedly fly some Venezuelans back to their country. Others may be given the opportunity to remain in Mexico, either by applying for asylum or residence. Some of those who were expelled immediately after the policy was announced were given 15-day exit permits and bus rides into the interior of Mexico, likely to keep them from trying to cross the U.S. border again.

Mexican authorities encountered around 36,000 Venezuelan migrants in the first seven months of this year but returned just 466 to Venezuela, and according to reports have not sent any back since July. Newly expelled Venezuelans might therefore be pushed back into other Latin American countries, adding to the possible ripple effects across the region.

New Parole Policy for Venezuelans

To be eligible for two-year humanitarian parole status, Venezuelans must be sponsored by a U.S. citizen, someone lawfully present in the United States, or an organization. Sponsors take financial responsibility for providing housing and helping arrivals access public benefits and find employment. Venezuelans must meet security and public health requirements, including COVID-19 vaccinations.

Venezuelans are ineligible for the program if they have been ordered removed from the United States within the past five years, arrived between ports of entry without authorization, or entered Mexico or Panama irregularly after the program was announced in mid-October. Dual nationals and permanent residents of another country are also ineligible, although family members of eligible Venezuelans may be exempt from this requirement. Some Venezuelans at the border may be also excepted from expulsion and paroled into the country for humanitarian reasons, although the Biden administration has declined to offer specifics.

Venezuelans must have a valid passport and apply for the program online. Accepted applicants will be allowed to travel to the United States by air, paroled in for a period of two years, and able to apply for work authorization.

Comparison with Other Parole Policies

The Venezuelan parole program on the surface mirrors some of the administration’s approaches to people fleeing the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Overall, the administration has relied less on the refugee resettlement process, which is traditionally slow. In fact, the United States admitted fewer than 200 refugees from Venezuela in FY 2022 and about 1,600 each from Afghanistan and Ukraine.

Instead, the administration has provided different forms of humanitarian protections to different nationality groups. In the wake of the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, DHS granted humanitarian parole to about 70,000 Afghans under Operation Allies Welcome. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Uniting for Ukraine program (U4U) has allowed for more than 87,000 Ukrainians to be approved to travel to the United States via parole as of September. (Nearly 25,000 Ukrainians also arrived at the U.S. southern border after the February invasion and many were granted parole). DHS has extended Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to Afghans and Ukrainians living in the United States before March 15 and April 19, 2022, respectively, making them eligible for work authorization. These programs come with relief from deportation and various degrees of public assistance. Afghans and Ukrainians can access refugee benefits, which include medical and food assistance, job training, and English classes; Venezuelans on humanitarian parole cannot access these benefits.

In January 2021, recognizing the ongoing Venezuelan crisis and the fact that a large number of Venezuelans lacked lawful U.S. status, the outgoing Trump administration granted them Deferred Enforced Departure (DED), another form of temporary relief from deportation. That March, the Biden administration made Venezuelans eligible for TPS; as of this June, 110,000 Venezuelans had received the status. But only Venezuelans who entered before March 8, 2021 are eligible, and the current TPS designation for Venezuela expires on March 10, 2024, at which time DHS must decide whether to renew it based on conditions in Venezuela.

What Is Different?

While Operation Allies Welcome and U4U are explicitly humanitarian in nature, DHS’s stated purpose for the Venezuelan policy is to “reduce the number of people arriving at our Southwest border and create a more orderly and safe process for people fleeing the humanitarian and economic crisis in Venezuela.” The relatively low cap of the Venezuelan parole program—24,000 people—is also dramatically lower than the numbers admitted through the U4U program, which has no cap.

The policy’s exclusion of Venezuelans arriving without authorization at the U.S. border or who irregularly entered Mexico or Panama is also unlike any prior parole program, and likely bars access to many migrants already en route. Since Mexico imposed visa requirements on Venezuelans in January (largely at the insistence of the U.S. government), thousands of Venezuelans have trekked on foot across the Darién Gap, a notoriously dangerous stretch of 67 roadless miles of jungle. Nearly 108,000 Venezuelans crossed the jungle in the first nine months of this year, including more than 38,000 in September. Thousands more have gathered in Necoclí, Colombia, waiting to cross the Darién Gap.

The denial of parole to dual nationals or permanent residents of another country also sets the Venezuelan program apart. Millions of displaced Venezuelans have been living elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean, and some have been granted various forms of temporary residence or work permits. While the details of the U.S. policy have not been fully spelled out, it seems possible that some Venezuelans will be excluded based on having received legal residence in another country, a condition that did not apply to Ukrainians.

Growing Numbers in Limbo

Venezuelans paroled into the United States will face the same issues as recent Afghan and Ukrainian arrivals. Their parole is valid for two years and does not provide a path to permanent lawful residence (also known as obtaining a green card). Thus, for more durable status, eligible Venezuelans will need to apply for asylum or other relief from deportation.

Since FY 2018, more than half of Venezuelan asylum cases have resulted in a grant of asylum. But more than 144,000 Venezuelan asylum cases remain pending in backlogged U.S. immigration courts and wait times for decisions can be years. Furthermore, recent Venezuelan arrivals who have permanent residence in another country may be ineligible for asylum under U.S. law..

Therefore, unless their parole is extended or Congress passes legislation authorizing paroled Venezuelans to adjust their status, many may not be able to stay lawfully, adding to an expanding pool of noncitizens with precarious legal status. As of February, nearly 355,000 people from 15 countries had TPS. Adding parolees from the Afghan, Ukrainian, and Venezuelan programs, there will be more than 500,000 noncitizens who must apply for asylum or other forms of relief to be eligible for U.S. lawful permanent residence. Legislation has been introduced in Congress to allow Afghan parolees to obtain a green card, but it has not received a vote.

Litigation Could Upend the Policy

In relying on Title 42, the Biden administration has tied its Venezuelan policy to the outcome of two ongoing court cases. When the administration first sought to terminate the use of Title 42 in April, 24 states sued, arguing in Arizona v. CDC that the move violated the Administrative Procedures Act. The following month, a federal district court in Louisiana granted a preliminary injunction keeping Title 42 in place temporarily. The federal government appealed and the case is now under review at the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Elsewhere, in Huisha-Huisha v. Mayorkas, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has challenged the government’s use of Title 42, arguing it was arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedures Act. While the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia found in March that using Title 42 against families was unlawful, it has yet to rule on the legality of the program as a whole—including, presumably, for Venezuelans.

Depending on the outcomes of these cases, it is possible that there will be two conflicting federal court decisions, suggesting the matter could end up at the Supreme Court.

The political reaction to the new policy has been swift. Migrant advocates and some Democratic leaders have pointed out the discordance of the Biden administration seeking to end use of the policy on the one hand, and dramatically expanding it on the other. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Menendez (D-NJ) strongly criticized the expanded use of Title 42, pointed out the disparate treatment for Ukrainians, and called for increases in refugee resettlement.

Some Democrats, however, including New York Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul, welcomed the policy, hoping that it will stem migrant arrivals. Biden critics, including Texas Governor Greg Abbott (R), suggested they had been vindicated and urged the administration to expand the policy and offer more assistance to border areas. Other conservatives called it an election-season attempt at appearing tough on immigration enforcement and criticized the use of parole to allow people into the country.

Root Causes and Regional Solutions

In announcing the approach, the Biden administration stressed its efforts to address migration push factors, including the government-wide Strategy for Addressing the Root Causes of Migration and the hundreds of millions of dollars it has pledged under the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection, a regional pact with countries in the Americas. Of the $817 million in foreign aid the United States has announced since September, $376 million is dedicated to humanitarian assistance for people affected by the Venezuelan crisis. As a part of the agreement with Mexico to accept Venezuelans, DHS this year also increased the number of H-2B seasonal nonagricultural visas—which are mostly used by Mexicans—by 65,000.

Critics from the region have pointed out that the U.S. government’s actions, particularly the parole program for 24,000 Venezuelans, pale in comparison to the reception provided by other countries. Indeed, 84 percent of the 7.1 million displaced Venezuelans remain in Latin America and the Caribbean, with others in Europe and Canada.

In the medium term, the Biden administration might be hoping for an improved economic and governance situation in Venezuela, which could stem the exodus and encourage some returns. There are reports Washington is considering lifting sanctions imposed by the Trump administration, giving the Venezuelan economy a boost. Such an act may be part of a broader rapprochement with the Maduro government. Mexico has hosted negotiations between Venezuela’s political opposition and government, and senior U.S. officials have expressed hope that an agreement could help address the humanitarian crisis. Access to U.S. markets for Venezuelan oil and Caracas accepting its removed nationals could also be up for discussion.

The authors thank Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh and Ari Hoffman for their research assistance.

Sources

Associated Press. 2022. Mexico Requires Visas for Venezuelans in Migrant Crackdown. Associated Press, January 6, 2022. Available online.

Baugh, Ryan. 2022. Annual Flow Report: Refugees and Asylees 2021. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security. Available online.

Bernal, Rafael. 2022. Menendez Comes Out against Biden’s Venezuelan Immigration Plan. The Hill, October 13, 2022. Available online.

Buschschlüter, Vanessa. 2022. Venezuela Crisis: 7.1m Leave Country Since 2015. BBC News, October 17, 2022. Available online.

Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc. (CLINIC). 2021. Updated Practice Advisory: Firm Resettlement Considerations in the Wake of the “Migrant Protection Protocols” Wind-Down. Washington, DC: CLINIC. Available online.

Cheatham, Amelia, Diana Roy, and Rocio Cara Labrador. 2021. Venezuela: The Rise and Fall of a Petrostate. Council on Foreign Relations, December 29, 2021. Available online.

Cohen, Luc. 2019. How Venezuela Got Here: A Timeline of the Political Crisis. Reuters, January 28, 2019. Available online.

Government of Mexico, Secretariat of Foreign Relations. 2022. México coordina con EE.UU. nuevo enfoque para una migración ordenada, segura, regular y humana en la región. Press release, October 12, 2022. Available online.

Herrero, Ana Vanessa. 2019. After U.S. Backs Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s Leader, Maduro Cuts Ties. The New York Times, January 23, 2019. Available online.

Human Rights First. 2022. Over 100 Groups Decry Linking Venezuelan Parole Plan to Title 42. Press release, October 14, 2022. Available online.

Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V). 2021. Recognized Refugees from Venezuela. Updated December 31, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Total Pending Asylum Claims Per Country. Updated December 31, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. RMNA 2022 - Refugee and Migrant Needs Analysis. N.p.: R4V. Available online.

---. 2022. Residence Permits and Regular Stay Granted. Updated August 5, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. R4V Latin America and the Caribbean, Venezuelan Refugees and Migrants in the Region - Sept 2022. N.p: R4V. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. Recent Migration Trends in the Americas. Buenos Aires and San José, Costa Rica: IOM. Available online.

Isacson, Adam. 2022. Weekly U.S.-Mexico Border Update: Title 42 for Venezuelans, Darién Gap, Foreign Ministers, Mexico Militarization, Texas. Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), October 14, 2022. Available online.

Kitroeff, Natalie and Anatoly Kurmanaev. 2022. With Migration Surging, U.S. Considers Easing Sanctions on Venezuela. The New York Times, October 12, 2022. Available online.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI), Migration Data Hub. N.d. U.S. Immigrant Population by State and County. Accessed October 14, 2022. Available online.

Miroff, Nick. 2021. Venezuelan Migrants Are New Border Challenge for Biden Administration. The Washington Post, November 23, 2021. Available online.

National Migration Service of Panama. N.d. Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por país según orden de importancia: Año 2022. Accessed October 25, 2022. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2021. Asylum Filings in Immigration Court by Hearing Location and Attendance, Representation, Nationality, Custody, Month and Year of Filing and Outcome. Updated November 2021. Available online.

---. 2022. Asylum Decisions by Custody, Representation, Nationality, Location, Month and Year, Outcome and More. Updated September 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Border Patrol Arrests. Accessed Updated July 2022. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation. Updated October 19, 2022. Available online.

---. N.d. Refugee Data Finder. Accessed October 17, 2022. Available online.

---. N.d. Venezuela Situation. Accessed October 14, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2022. CDC Public Health Determination and Termination of Title 42 Order. Media statement, April 1, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2022. DHS Announces Re-Registration Process for Current Venezuela Temporary Protected Status Beneficiaries. Press release, September 7, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Process for Venezuelans. Updated October 14, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2022. Nationwide Encounters. Updated September 14, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2020. Control of Communicable Diseases; Foreign Quarantine: Suspension of Introduction of Persons into United States from Designated Foreign Countries or Places for Public Health Purposes. Federal Register 85, no. 57. March 24, 2020. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response. 2022. Renewal of Determination that a Public Health Emergency Exists. October 13, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2021. Secretary Mayorkas Designates Venezuela for Temporary Protected Status for 18 Months. Press release, March 8, 2021. Available online.

---. 2022. Department of Homeland Security Operation Allies Welcome Afghan Evacuee Report. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

---. 2022. DHS Announces Extension of Temporary Protected Status for Venezuela. Press Release, July 11, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. DHS Announces New Migration Enforcement Process for Venezuelans. Press release, October 12, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Implementation of a Parole Process for Venezuelans. Federal Register 87, no. 201. October 19, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Legal Immigration and Adjustment of Status Report Fiscal Year 2022, Quarter 2. Updated October 7, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Operation Allies Welcome. Updated September 29, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Refugees and Asylees. Accessed October 17, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. 2022. 2020 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

U.S. Department of Justice. 2022. Executive Office for Immigration Review Adjudication Statistics: Total Asylum Applications. Washington, DC: Department of Justice. Available online.

Wilson, Jill H. 2022. Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Wolfe, George. N.d. Where Are Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees Going? An Analysis of Legal and Social Contexts in Receiving Countries. New York: Center for Migration Studies. Available online.