You are here

‘Recalcitrant’ and ‘Uncooperative’: Why Some Countries Refuse to Accept Return of Their Deportees

A migrant scheduled to be deported from the United States is escorted to a charter flight. (Photo: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement)

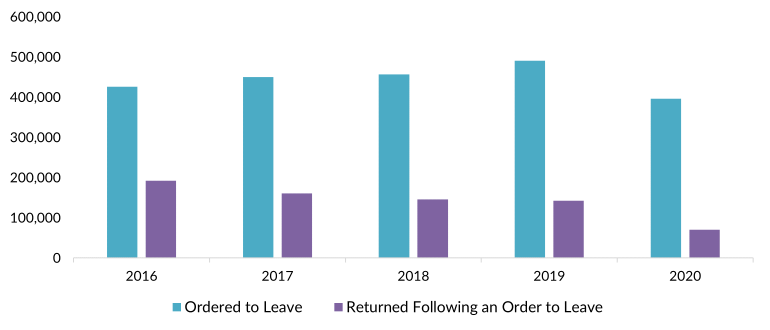

Some of the world’s most powerful countries, including the United States and those in the European Union, have had their immigration policies frustrated by smaller nations that refuse to accept their nationals designated for return. Although the United States regularly deports more than 200,000 people each year, nearly 1.2 million noncitizens who had been ordered removed had not left the country as of January 2021, according to a federal court filing; in 2020, only about 18 percent of people who had received such orders were deported. This includes cases on appeal as well as noncitizens ordered to return to China, Cuba, and other countries that the United States has labeled “recalcitrant” because they will not accept their nationals.

In the European Union, just 19 percent of non-EU citizens with orders to leave were returned to countries outside Europe during the 2015-19 period, according to European Court of Auditors estimates. Return data are notoriously flawed, given the poor quality of available EU statistics and variation in national reporting. Nonetheless, such low numbers indicate major obstacles in effectively enforcing this aspect of immigration law. A major reason for this is what the European Union terms “uncooperative” countries of origin.

Effective returns are the cornerstone of a functional and credible migration system. If irregular migrants face little risk of deportation, they have less reason to comply with orders to leave voluntarily. A nonfunctioning system can also be a lure to would-be migrants if they sense there is little risk to irregular arrival. Additionally, the failure to enforce legal orders to return might push policymakers towards more restrictive border policies. Put simply, if return policies fail, they are likely to be supplemented by nonadmission policies.

Deportation is more formally referred to in the United States and United Kingdom as “removal” and in much of continental Europe as “return.” The enforcement action is widely perceived to pit destination states against unauthorized migrants, but it also pits destination states against origin states. Destination countries cannot unilaterally send back asylum seekers whose claims are denied and other migrants without residence permits, but must depend on origin states’ willingness to readmit them and assist with their identification and travel documents. (Forced return is typically more difficult to implement than assisted return; while both might be understood as deportation, this article’s focus is on the former.)

Legally speaking, is there a duty for origin states to readmit their nationals? Most legal scholars agree that there is, according to research by Özlem Gürakar-Skribeland, even if the duty’s exact nature and scope are not precisely defined. With basic legal safeguards in place, few would dispute a government’s right to lawfully expel a non-national from its territory. As a logical corollary, one may argue, there is a corresponding duty upon the state where the national comes from to readmit them. In endorsing the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration in 2018, 163 countries committed to “ensure that our nationals are duly received and readmitted, in full respect for the human right to return to one’s own country and the obligation of states to readmit their own nationals.”

Yet origin states have political, economic, and cultural reasons not to accept their returning nationals. This article examines the reasons why countries may refuse to collaborate on returning their nationals and strategies that destination countries have taken to compel them. It draws from work supported by the Research Council of Norway’s UTENRIKS grant program, through the project Deporting Foreigners: Contested Norms in International Practice (NORMS, 2021-25).

Why Origin States May Not Want to Collaborate

The simple and predominant explanation for why origin states may not want to collaborate on return and readmission is that the costs of doing so are high and that they lack appropriate incentives. For political elites in origin countries, the issue is often highly sensitive. Collaboration—which may sometimes be interpreted as subservience—likely serves neither their country’s economic interests, as it cuts off remittances, nor their own political interests, as it alienates the electorate.

Accepting returnees may be seen as a security risk. For instance, taking back emptyhanded and frustrated young men, who are sometimes stigmatized as failed migrants and criminals, may be seen as risky by politicians in fragile states. Whether deportees do indeed pose a risk to the state varies, but at least in some cases these fears may be valid.

In the 1990s, for instance, U.S. deportations to Central America contributed to the regional rise of Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), a major gang and transnational criminal organization founded in the United States by Central American migrants. In recent years, Gambians have protested high volumes of planned returns from the European Union. Many criticized the proposal as inhumane and putting pressure on a nascent democracy struggling to move on from the two-decade dictatorship of Yahya Jammeh; in response, the government refused to accept returns from the European Union. During the COVID-19 pandemic, removals from the United States were seen by the government in Guatemala and opposition politicians in Jamaica as potential public-health hazards that could strain local health-care systems.

Figure 1. Non-EU Citizens Ordered to Leave and Returned Following an Order to Leave, 2016-20

Note: Figure refers to orders to leave EU territory and includes returns to non-EU Member States on the European continent. The return rate is much lower for countries outside Europe. Data also do not include the United Kingdom, a former EU Member State. For a more general critical reflection on the return rate and its analytical shortcomings, see Philipp Stutz and Florian Trauner.

Source: Eurostat, “Third Country Nationals Ordered to Leave – Annual Data (Rounded),” updated September 14, 2022, available online; Eurostat, “Third Country Nationals Returned Following an Order to Leave - Annual Data (Rounded),” updated September 14, 2022, available online; Philipp Stutz and Florian Trauner, “The EU's “Return Rate” with Third Countries: Why EU Readmission Agreements Do Not Make Much Difference,” International Migration 3, no. 60 (2022): 154-72, available online.

Geopolitical Elements

These are perceived strategic costs for origin states (and transit states, too, although this article focuses primarily on dynamics between destination and origin countries). Yet it would be misguided to explain their reluctance only in terms of a rationalist cost-benefit analysis. Broader and deeper issues also are at play.

Deportation is a symbol of international power. Electorates in origin states may view readmission as a kind of betrayal, in which their government sides with a foreign country rather than its own nationals. Immigration policies sort individuals into desirables and undesirables, and the removal process expresses this dramatically and visibly. To allow in migrants from one country but not another is to express a geopolitical dynamic, and to deport undesirable migrants can be seen as adding insult to injury. Geopolitical tensions, such as between the United States and Cuba, exacerbate this issue and therefore complicate return. In April 2022, U.S. and Cuban officials met to discuss the possible resumption of removal flights to Cuba; in exchange, Cuba has pressed for the United States to honor a suspended commitment to issue 20,000 green cards annually for Cubans. Inversely, good diplomatic relations facilitate return, as evidenced by EU Member States’ bilateral ties and agreements to facilitate return, weakening the bloc’s collective bargaining power.

There is a postcolonial power dynamic to this as well. Colonial-era logic continues to guide mobility patterns, and removal often sends poor migrants back to former colonies. The lowest return rates for the European Union as of the 2008-18 period were to sub-Saharan Africa; just 10 percent of people ordered to return to West African countries had been returned as of 2018, the rate was 17 percent for those ordered returned to Eastern and Central Africa, 38 percent for those with orders to return to Central and South Asia, and 41 percent for those ordered returned to the Middle East and North African region.

The case of Morocco is illustrative: Moroccan officials may see EU visa policies and return of their nationals as an affront to civic pride, even if they do not say so formally, according to research by Nora El Qadim. Government officials also do not necessarily agree that the people they are requested to readmit are in fact Moroccan, given that it can be difficult to verify a migrant’s identity. Declaring whether someone is a citizen is, for the origin country, an expression of sovereign control, much like removing an unauthorized migrant is for a destination country.

The United States and the European Union and its Member States also sometimes return non-nationals to transit countries, merely on account of them having passed through. Transit countries are typically reluctant to accept the migrant, and the legal basis for the transaction is somewhat unclear. When, for instance, the European Union wanted to deport unauthorized migrants to Morocco following a surge in arrivals to Spain’s Canary Islands in 2020, Morocco rejected the request, insisting that it is not responsible for nationals from other countries. Partly as a result, governments have taken to securing agreements with transit countries such as Libya and Turkey, at times trading economic and other assistance for support on migration enforcement.

How Countries Resist Accepting Returnees

It is comparatively rare for origin states to openly refuse to take back a documented national. Iran is one of few to flatly refuse forced returns from at least some EU Member States (although notably not from Germany), citing the Iranian constitution as its legal basis and its preference for assisted return programs. As mentioned above, the Gambia previously enacted a public moratorium on forced returns from EU Member States, citing security. But these are exceptional cases.

More typically, nonresponse or bureaucratic obstacles make returns difficult, if not impossible. If, for instance, the U.S. government approaches an origin country’s embassy to request assistance in verifying identification and issuing travel documents as part of a removal, that country has various tools at its disposal to complicate the return. It can simply not respond, or else impose such a high bar for verifying identification that it would be nearly impossible to prove that the deportee is in fact one of its nationals. Alternatively, it can blame delays on a lack of administrative capacity and inadequate national registries.

These challenges can be real, but they can also be convenient measures to avoid cooperation. For instance, some origin states prefer deportations via commercial flights over special charter flights, partly because the latter is a more visible embarrassment and partly because a sudden inflow of returnees can cause logistical problems. Moreover, it is not an easy task to ascertain whether someone is a citizen if they hold a fabricated ID or have no paperwork and, importantly, do not want to be identified. The challenges occur on both sides: the United States has in recent years accidentally detained or deported hundreds of U.S. citizens, and the UK Home Office likewise unlawfully detained and deported Commonwealth citizens who arrived from Caribbean countries between 1948 and 1971 as part of the Windrush generation.

No origin state wants to accept a noncitizen by mistake. And no public official wants to be pressured to do so by agents from a foreign state, who themselves may be under political pressure to increase returns. Lean too heavily on that public official with too weak a case, and goodwill and trust dissipate, further sanding the wheels of readmission. As such, it can be difficult for returning states to know what and who is behind the lack of collaboration.

Policy Dilemmas for States Carrying Out Removals

The resultant opacity leaves deporting states in a conundrum. Politically motivated noncollaboration requires a different response than a simple dysfunctional bureaucracy.

For policymakers, the ultimate question is therefore bewilderingly complex: Why is the return rate to a specific origin state low? Flawed presumptions can lead to costly overreactions. It is therefore not straightforward for destination countries to know how much political capital to invest in carrying out removals. Yet declining to enforce a deportation likely means detaining someone for months, demanding huge administrative resources, or releasing them, which comes with a domestic political cost. It also generates concerns over public safety when noncitizens—some with criminal convictions—become effectively undeportable.

Officials can bypass the embassy and contact the origin country government directly, but this comes with diplomatic risks. Alternatively, they can exercise political leverage by naming and shaming countries that refuse to cooperate—or escalate further by halting issuance of some visas to nationals of so-called recalcitrant or uncollaborative countries.

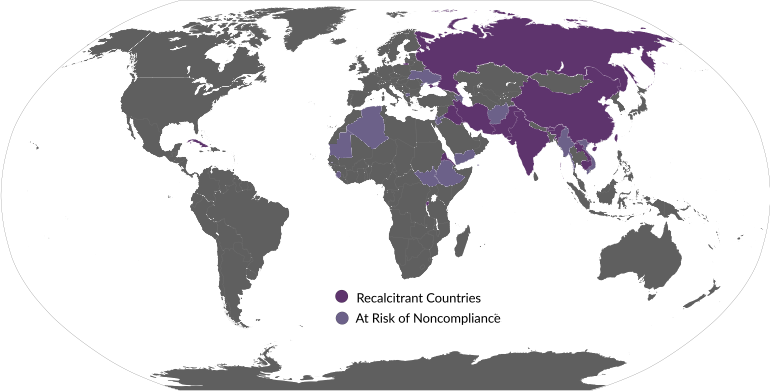

The United States has long taken an assertive approach. As of mid-2020, it considered 13 countries and territories recalcitrant: Bhutan, Burundi, Cambodia, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Hong Kong, India, Iran, Iraq, Laos, Pakistan, and Russia. Several more were publicly identified as being at risk of the classification (see Figure 2). Varying degrees of visa sanctions were as of this writing in effect for eight countries: Cambodia, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Laos, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Sierra Leone. In previous years, the United States has imposed visa penalties against Burundi, Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, and Guyana. The fact that some countries have moved off the sanctions list could be read as indication of at least partial success of the pressure campaign.

Figure 2. Countries Identified by the United States as Uncooperative on Removals, 2020

Note: Figure includes countries the U.S. government has labeled “recalcitrant” as well as those at risk of noncompliance, meaning they demonstrate only partial cooperation.

Source: Jill H. Wilson, Immigration: “Recalcitrant” Countries and the Use of Visa Sanctions to Encourage Cooperation with Alien Removals (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2020), available online.

At times, countries identified as being uncooperative have been the origins for a sizable share of unauthorized migrants. In 2016, slightly more than one-quarter of the 954,000 noncitizens in the United States with outstanding orders of removal were from countries deemed recalcitrant or otherwise uncooperative, according to then-Sen. Jeff Sessions (R).

Not all deporting states have the geopolitical muscle of the United States, however, nor the desire to be confrontational. Canada, for instance, has long refrained from naming and shaming. It is unclear whether this is due to a desire to avoid stigmatizing specific national groups, a preference for quiet diplomacy, or lack of political commitment to ensure return.

In the European Union, A Shift Towards Conditionality

The European Union has sought to take a harder line on uncollaborative countries, even if it struggles to combine a multilateral approach, geopolitical muscle, and the bilateral ties between some Member States and origin countries. For roughly two decades, the bloc has poured financial and political investments into formal readmission agreements and, increasingly, more informal and legally nonbinding readmission arrangements, combined with more use of conditionality.

Seemingly inspired by the United States as well as mounting domestic political pressure, Brussels has increasingly made cooperation on returns a condition for receiving various types of support. Attaching conditions for development aid and other assistance is nothing new, but these strings have intensified amid low return rates and high levels of migrant arrivals in recent years, especially following the spike in migration in 2015-16.

One example is the Global Europe: Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI), the main financing mechanism for external cooperation, which ties some support to migration-related cooperation. Through NDICI, the European Union has earmarked 79.5 billion euros for collaboration with third countries from 2021 to 2027.

The European Union also has more recently experimented with visa sanctions for certain countries deemed uncooperative, though in a somewhat more limited and narrow scope than the U.S. actions. In 2019, the visa code’s Article 25(a) was revised to link the EU short-stay visa policy to countries’ cooperation on readmission. As a result, the European Union identified Bangladesh, the Gambia, and Iraq as uncooperative in July 2021, and threatened to impose temporary restrictions on short-stay visas for their citizens. This measure was imposed on the Gambia, prompting it to lift its moratorium on forced return in March 2022, although EU restrictions remained in place as of October. But enhanced cooperation by Bangladesh and Iraq allowed their nationals to avoid visa sanctions. As in the United States, this could indicate at least partial success of the strategy.

Both the NDICI and the revised visa code have been controversial in Europe, with much of the disagreement centering on the effectiveness and legitimacy of using conditionality to make origin states collaborate. Both policies are part of the migration-development nexus. NDICI’s direct link with that nexus raises questions about how the bloc can promote ownership over developmental interventions and an equitable developmental partnership through a carrot-and-stick policy. The revised visa code is not presented as part of the migration-development nexus, but it constrains mobility to the European Union and likely limits the developmental impact for origin states such as the Gambia. On the other hand, using mobility as a bargaining chip could be perceived as more legitimate by origin states, in that its tit-for-tat logic is straightforward. It could therefore potentially be easier for political elites in origin states to communicate this to voters as an appropriate bargain.

Towards a New Policy and Research Agenda

Few would argue that countries do not have the fundamental right to regulate the entry of foreign nationals. Likewise, few origin states protest deportations openly and as a matter of principle. Those that resist readmission most commonly do so by failing to respond to a country’s request or erecting cumbersome bureaucratic hurdles. Bureaucracy, in this context, is the weapon of the weak.

Scholars and policymakers alike too often understand the situation as a simple matter of costs and benefits, prompting efforts to create better incentives and harsher sanctions and exploring the effectiveness of such a carrot-and-stick approach. Yet to understand why origin states are recalcitrant, it is worth exploring more constructivist approaches too. Far away from Washington and Brussels, return is often politically fraught in poorly understood ways, and the normative duty to readmit collides with other legal, political, and cultural norms, as sketched out above.

Drawing on an analytical framework developed by James G. March and Johan P. Olsen, the rationalist “logic of consequences” complements and interacts with the “logic of appropriateness” in the field of return and readmission. Within the former logic, the question of whether to readmit is merely about national interests and hard power. Within the latter, readmission takes place if it is viewed as natural, rightful, expected, and legitimate. Neither logic is sufficient alone but using both brings about a better understanding of a normatively charged issue and a complicated dynamic.

Sources

El Qadim, Nora. 2014. Postcolonial Challenges to Migration Control: French-Moroccan Cooperation Practices on Forced Returns. Security Dialogue 45 (3): 242-61.

---. 2018. The Symbolic Meaning of International Mobility: EU–Morocco Negotiations on Visa Facilitation. Migration Studies 6 (2): 279-305.

European Commission. 2022. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Report on Migration and Asylum. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

European Court of Auditors. 2021. EU Readmission Cooperation with Third Countries: Relevant Actions Yielded Limited Results. Luxembourg: European Court of Auditors. Available online.

Gürakar-Skribeland, Özlem. 2022. Forced Return of Migrants to Transit Countries: A Case of Competing Sovereigns. Doctoral dissertation, the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, Oslo, University of Oslo.

Kessler, Glenn. 2022. Mayorkas’s Claim that Undocumented Immigrants Are ‘Promptly Removed.’ The Washington Post, May 5, 2022. Available online.

March, James G. and Johan P. Olsen. 2004. The Logic of Appropriateness. Oslo: Arena.

Reuters. 2020. Morocco Rebuffs EU Request to Re-Admit Third-Country Migrants. Reuters, December 15, 2020. Available online.

Stutz, Philipp and Florian Trauner. 2022. The EU's “Return Rate” with Third Countries: Why EU Readmission Agreements Do Not Make Much Difference. International Migration 60 (3): 154-72. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2022. Visa Sanctions Against Multiple Countries Pursuant to Section 243(d) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Updated August 17, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Senator Jeff Sessions. 2016. 242,772 Aliens with Final Removal Orders from Recalcitrant and Non-Cooperative Countries Remain in the United States. Press release, October 19, 2016. Available online.

Wilson, Jill H. 2020. Immigration: “Recalcitrant” Countries and the Use of Visa Sanctions to Encourage Cooperation with Alien Removals. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Zanker, Franzisca, Judith Altrogge, Kwaku Arhin-Sam, and Leonie Jegen. 2019. Challenges in EU-African Migration Cooperation: West African Perspectives on Forced Return. Kiel, Germany: Mercator Dialogue on Migration and Asylum (MEDAM). Available online.