You are here

Immigrant Health-Care Workers in the United States

An intern examines a newborn baby in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of the Naval Medical Center San Diego. (Photo: Joseph A. Boomhower/U.S. Navy)

The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a bright light on the U.S. health-care system like no other recent crisis. Doctors, nurses, and other health-care professionals were praised for stepping up to confront the major public-health challenge. While the waning of the pandemic has relieved some pressure on the U.S. health-care system, longstanding challenges remain, including the aging of both the overall U.S. population and health-care workers, geographic mismatches between health providers and vulnerable populations, and the persistent under-representation of racial and ethnic minorities.

Immigrants account for disproportionately high shares of essential workers across the U.S. economy and were on the front lines as part of the U.S. response to the pandemic. If recent immigration, education, and health-care trends continue, immigrants’ presence in the health-care sector will only increase going forward.

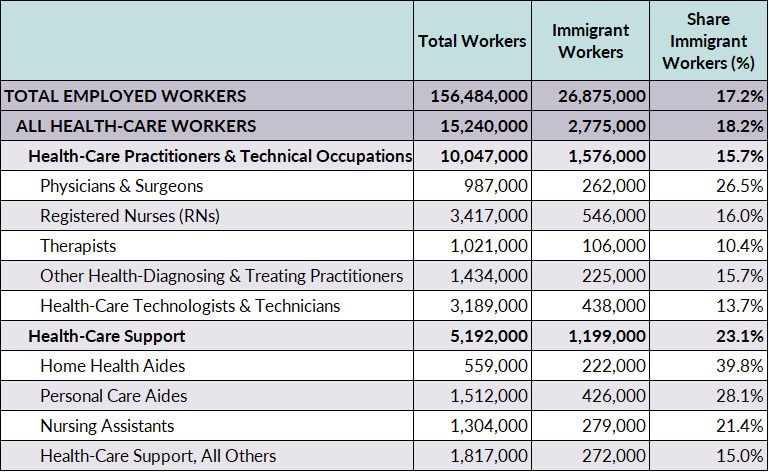

Nearly 2.8 million immigrants were employed as health-care workers in 2021, accounting for more than 18 percent of the 15.2 million people in the United States in a health-care occupation. This was slightly higher than immigrants’ share of the overall U.S. civilian workforce (17 percent) and the foreign born were especially over-represented among certain health-care occupations such as physicians and surgeons (26 percent) as well as home health aides (almost 40 percent). Approximately 1.6 million immigrants were working as doctors, registered nurses, dentists, pharmacists, or dental hygienists.

Immigrants in the health-care sector hold a variety of legal statuses; among them are naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents, temporary workers, and recipients of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Female immigrants were more likely than U.S.-born women to work in direct health-care support occupations known for low wages, such as home health aides and nursing assistants. In contrast, immigrant men were more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to be physicians and surgeons, occupations that are well compensated. Compared to all immigrant workers, those employed in the health-care field were more likely to speak English fluently, be naturalized citizens, and hold health insurance coverage.

While immigrants play a vital role at all levels of health care, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that 270,000 immigrants with a college degree in medical and health sciences and services were on the sidelines of the pandemic because of skill underutilization—that is, because they were working in lower-skilled jobs, such as registered nurses working as health aides—or were out of work. Like immigrants employed in health care overall, most of these underemployed immigrant health-care professionals are bilingual. They speak a variety of non-English languages (such as Spanish, Tagalog, Chinese, Arabic, Korean, Hindi, and Russian) also spoken by U.S. residents who are Limited English Proficient (LEP) and who may receive health-care services of lower quality because of language and cultural barriers.

This Spotlight provides a demographic and socioeconomic profile of foreign-born health-care workers residing in the United States. The data come primarily from the U.S. Census Bureau's 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). All data refer to civilian, employed workers ages 16 and older, unless otherwise noted.

Definitions

Foreign born" and "immigrant" are used interchangeably and refer to persons with no U.S. citizenship at birth. This population includes naturalized citizens, lawful permanent residents, refugees and asylees, persons on certain temporary visas (including those on student or work visas), and unauthorized immigrants.

The terms “U.S. born” and “native born” are used interchangeably and refer to persons with U.S. citizenship at birth, including those born in Puerto Rico or abroad born to a U.S.-citizen parent.

Most analyses in this article divide health-care occupations into the following occupational groups:

Health-Care Practitioners and Technical Occupations

- Physicians and surgeons

- Registered nurses (RNs)

- Therapists (including occupational therapists, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and speech-language pathologists)

- Health-care technologists and technicians (including clinical laboratory technologists and technicians, dental hygienists, emergency medical technicians and paramedics, licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses, pharmacy technicians, and radiologic technologists and technicians)

- Health practitioners and technical occupations, all others (including dentists, nurse practitioners and nurse midwives, optometrists, pharmacists, physician assistants, podiatrists, and veterinarians).

Health-Care Support Occupations

- Home health aides

- Personal care aides

- Nursing assistants

- Health-care support, all others (including dental assistants, massage therapists, medical assistants, phlebotomists, and physical therapist assistants and aides)

Click on the bullet points below for more information:

- Historical Trends and Projections

- Number and Share Nationally and by State

- Gender

- Region and Country of Birth

- Education, Naturalization, and Language Proficiency

- Visa Pathways

- Health Insurance Coverage

Historical Trends and Projections

Approximately 15.2 million native-born and immigrant workers were employed in health-care occupations in 2021, up from 12 million in 2010. Health-care occupations are projected to account for about 2 million of the 8.3 million jobs expected to be created in the United States between 2021 and 2031, according to BLS estimates.

Health-care jobs fall into two broad categories: health-care practitioners and technical occupations (accounting for about 10 million workers in 2021), and health-care support occupations (5.2 million). Health-care support occupations are expected to grow by 18 percent between 2021 and 2031, the fastest of the 22 broad occupational groups analyzed by BLS. The number of health-care practitioners and technical occupations is projected to increase by about 9 percent, while overall U.S. employment is expected to grow by 5 percent.

Several factors explain these upward projections. The aging and longer life expectancy of the U.S. population is driving the demand for care and treatment of chronic illnesses. So is the aging and retirement of current health-care workers and those who teach in medical and nursing schools. For example, about 18 percent of physicians, surgeons, and registered nurses are within ten years of expected retirement (meaning they were between ages 55 and 64) as of 2021. The lengthy time needed to acquire education and on-the-job training in health-care occupations makes it harder to switch between professions in response to new job opportunities, while professional licenses often restrict geographic mobility and, for those trained internationally, access to the profession.

Click here for more information about the BLS employment projections methodology.

Number and Share Nationally and by State

Immigrant professionals have long played an important role in the U.S. health-care workforce and make up disproportionate shares of both certain high- and low-skilled health-care workers. For instance, the foreign born accounted for 26 percent of the 987,000 physicians and surgeons practicing in the United States in 2021 and almost 40 percent of the 559,000 home health aides (see Table 1).

Table 1. Civilian Employed Workers (ages 16 and older) and Health-Care Workers, by Occupational Group and Nativity, 2021

Note: The estimates of health-care workers here refer to their numbers by occupation, regardless of their industry of employment (many occupations can span several industries).

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2021 American Community Survey (ACS).

The immigrant share of the health-care workforce was roughly twice the national level in New York (37 percent) and California (35 percent). Other states with high shares in 2021 were New Jersey (32 percent), Florida (30 percent), Maryland and Hawaii (26 percent each), and Nevada (24 percent).

In a number of states, immigrants make up much higher shares of physicians and surgeons than of all health-care workers or all workers in general. In Michigan, for example, immigrants accounted for only 8 percent of all workers and 9 percent of health-care workers in 2021, but 28 percent of physicians and surgeons. Other places relying heavily on foreign-born physicians and surgeons include New Jersey (37 percent); Florida (35 percent); New York (33 percent); and California, the District of Columbia, and Maryland (32 percent each).

State-Level Data on Immigrant Health-Care Workers

Click here to access detailed information on the immigrant share among health-care workers overall and by select occupation for all 50 states.Several states also have high shares of registered nurses (RNs) who are immigrants. Nationwide, the foreign born account for 16 percent of RN jobs, but the numbers are much higher in California (37 percent), Nevada (34 percent), New Jersey (32 percent), and Florida and the District of Columbia (29 percent each).

In several states, immigrants account for large shares of low-skilled health-care workers, such as home health aides. New York had the highest share of immigrant home health aides in 2021 (74 percent), followed by Florida (60 percent), Maryland (55 percent), and New Jersey (54 percent).

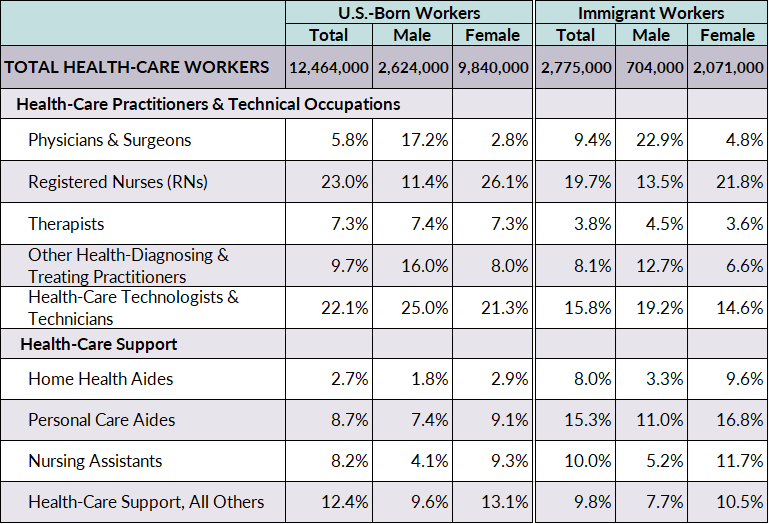

Regardless of nativity, women are more likely than men to be employed as RNs and in health-care support occupations and less likely to be physicians and surgeons (see Table 2). Both immigrant men and women employed in health-care occupations in 2021 were more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to work as physicians and surgeons; 23 percent of foreign-born men and 5 percent of foreign-born women employed in health care worked in these professions, compared to 17 percent of native-born men and 3 percent of native-born women.

Foreign-born health-care workers overall are also more likely than their native-born peers to work as nursing assistants, personal care aides, and home health aides. Among the foreign born, 38 percent of women and 19 percent of men worked in these occupations in 2021, compared to 21 percent of U.S.-born women and 13 percent of U.S.-born men.

Table 2. Occupational Distribution of Civilian Employed Health-Care Workers (ages 16 and older), by Nativity and Sex, 2021

Note: The estimates of health-care workers here refer to their numbers by occupation, regardless of their industry of employment (many occupations can span several industries).

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2021 ACS.

Regardless of nativity, most health-care occupations rely on female workers. Women accounted for 75 percent of the 2.8 million immigrant health-care workers in 2021, and 79 percent of the 12.5 million U.S.-born health-care workers. Women represented the lion’s share of both foreign- and native-born registered nurses (83 percent and 90 percent, respectively). Similarly, foreign- and native-born women accounted for approximately 86 percent and 89 percent, respectively, of home health aides, who tend to be low-paid. In contrast, 38 percent of both foreign- and U.S.-born physicians and surgeons were women.

Region and Country of Birth Data on Immigrant Health-Care Workers

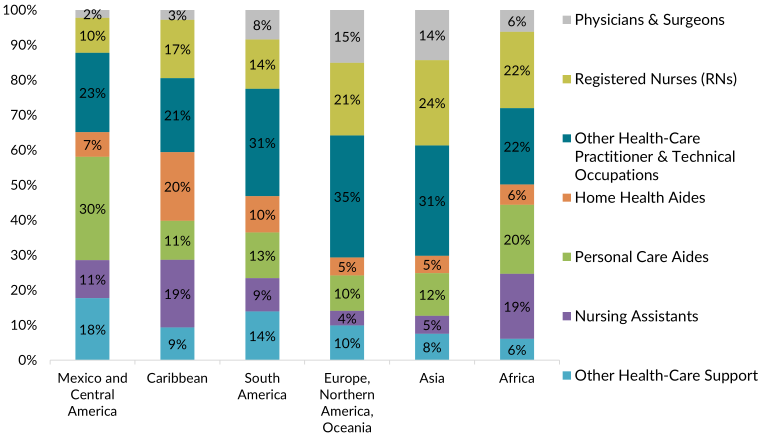

Click here to access information on the immigrant share among health-care workers overall and by select occupation for regions and countries of birth.Asia was the leading region of birth for immigrant health-care workers in 2021, accounting for 39 percent, followed by the Caribbean (16 percent); Mexico and Central America (15 percent); Africa (13 percent); Europe, Northern America, and Oceania (12 percent collectively); and South America (6 percent).

Asia-born health-care workers and those from Europe, Northern America, and Oceania were more likely than their counterparts from other regions to work as physicians and surgeons and, along with those born in Africa, as RNs (see Figure 1). In contrast, 65 percent of immigrant health-care workers from Mexico and Central America, 59 percent from the Caribbean, 50 percent from Africa, and 47 percent from South America were employed in health-care support occupations.

Figure 1. Immigrant Civilian Employed Health-Care Workers (ages 16 and older), by Region of Birth and Occupation, 2021

Note: The estimates of health-care workers here refer to their numbers by occupation, regardless of their industry of employment (many occupations can span several industries).

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2021 ACS.

Immigrants from the Philippines accounted for 27 percent of the 546,000 immigrants working as registered nurses, followed by those from India (7 percent), Mexico and Jamaica (5 percent each), and Nigeria and Haiti (4 percent each). Among the 262,000 immigrant physicians and surgeons, Indians were the top group with 21 percent, followed by those from China/Hong Kong (6 percent), Pakistan and Canada (5 percent each), and the Philippines (4 percent). Among 222,000 immigrant home health aides, the top countries of origin were the Dominican Republic (19 percent), China/Hong Kong (10 percent), Mexico (9 percent), Jamaica (8 percent), and Haiti (5 percent). Mexico (22 percent), the Philippines (11 percent), China/Hong Kong and Nigeria (4 percent each) were the top four countries of birth of the 426,000 immigrants who worked as personal care aides.

Education, Naturalization, and Language Proficiency

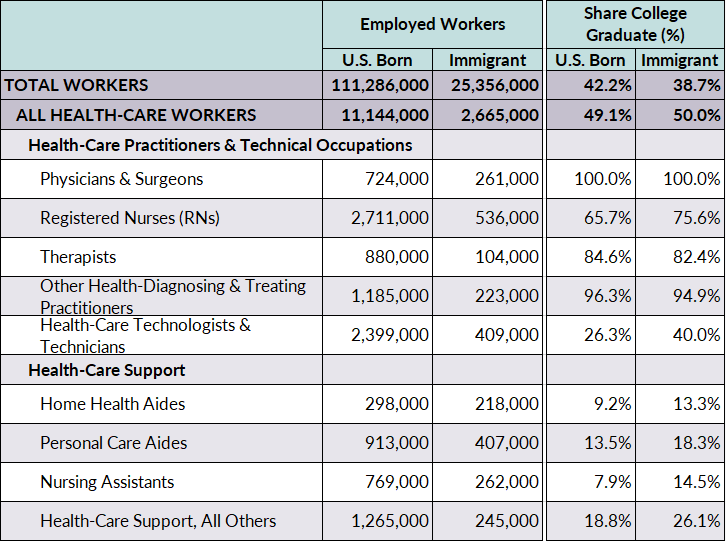

Overall, immigrant workers ages 25 and older in health-care occupations were roughly equally as likely as their native-born counterparts to have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher; about half of both populations were college graduates. The nativity differences in educational attainment are more pronounced in some occupations: Immigrant health-care workers employed as registered nurses, health-care technologists and technicians, and health-care support occupations were particularly more likely to have received a four-year college education than their U.S.-born counterparts (see Table 3).

Table 3. Educational Attainment for Overall Civilian Employed Population (ages 25 and older) and Health-Care Workers, by Occupational Group and Nativity, 2021

Note: The estimates of health-care workers here refer to their numbers by occupation, regardless of their industry of employment (many occupations can span several industries).

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2021 ACS.

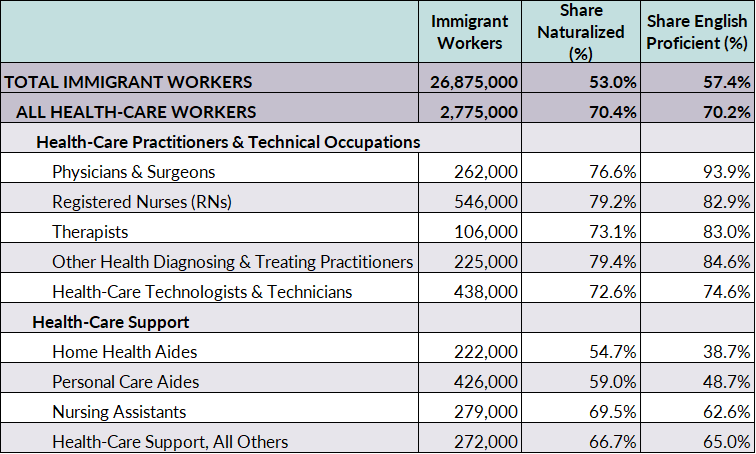

About 70 percent of immigrant health-care workers were U.S. citizens in 2021, compared to 53 percent of all immigrants in the U.S. workforce. The share varies by occupation, ranging from about 79 percent for RNs and other health-diagnosing and treating practitioners, 77 percent for physicians and surgeons, and 55 percent for home health aides (see Table 4).

Table 4. Naturalization Share and English Proficiency of Immigrant Health-Care Workers (ages 16 and older), by Occupational Group, 2021

Notes: The term “English proficient” refers to workers who reported speaking English exclusively or "very well." The estimates of health-care workers here refer to their numbers by occupation, regardless of their industry of employment (many occupations can span several industries).

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2021 ACS.

Approximately 70 percent of foreign-born health-care workers reported speaking English proficiently (meaning exclusively or "very well"), which was markedly more than among all civilian employed foreign-born workers (about 57 percent). Most immigrants in the health-care practitioners and technical occupations reported high degrees of English proficiency. However, less than half of home health aides and personal care aides were fully English proficient.

Foreign-born health-care workers are admitted to the United States under a variety of temporary and permanent visa categories. Temporary visa categories include H-1B (for those in specialty occupations), TN (for Mexican and Canadian professionals under the North American Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA]), J-1 (for exchange visitors), O-1 (for persons with "extraordinary ability or achievement"), and E-3 (for workers from Australia in specialty occupations). As is the case with other immigrants, those in the health-care sector can be admitted through permanent immigration channels (also known as getting a green card) based on family, employment, or humanitarian protection routes.

It is hard to assess how many foreign-born health professionals arrive annually, whether via temporary or permanent visa channels, because, for the most part, visa data are not broken down by occupation. Since most health-care occupations require a professional license, relatively few foreign nationals meet the requirement unless they obtain a U.S. degree and complete the necessary postgraduate training. Some doctors with foreign degrees are able to apply for a J-1 visa to complete a medical residency in the United States.

Despite the key role immigrants play, the U.S. immigration system has typically not prioritized attracting foreign-born health-care professionals. Less than 5 percent (or 5,800) of the 123,400 H-1B petitions approved for initial employment in fiscal year (FY) 2021 went to workers in health-care and medicine occupations, including 2 percent (or 2,800) for physicians and surgeons. The lion’s share (61 percent) of approved H-1B petitions for initial employment in FY 2021 went to workers in computer-related occupations, according to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Most workers employed in health-care occupations had health insurance in 2021, regardless of their occupation or nativity. Immigrants employed in health-care occupations were much less likely to be uninsured (9 percent) than those in other occupations (21 percent).

While nearly all physicians, surgeons, and RNs had coverage regardless of nativity, about 13 percent of immigrant and 11 percent of U.S.-born health-care support workers lacked health insurance.

Sources

American Medical Association. 2019. New Policy Aimed at Increasing Diversity in Physician Workforce. Press release, June 12, 2019. Available online.

Batalova, Jeanne and Michael Fix. 2022. Leveraging the Skills of Immigrant Health-Care Professionals in Illinois and Chicago. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Batalova, Jeanne, Michael Fix, and José Ramón Fernández-Peña. 2021. The Integration of Immigrant Health Professionals: Looking Beyond the COVID-19 Crisis. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2022. Employment Projections: Occupational Projections and Worker Characteristics. Updated September 8, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. 2021 American Community Survey. Accessed from Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Matthew Sobek, Danika Brockman, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, and Megan Schouweiler. IPUMS USA: Version 13.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2022. Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers: Fiscal Year 2021 Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC: USCIS. Available online.