You are here

Generations of Palestinian Refugees Face Protracted Displacement and Dispossession

A Palestinian woman in Bani Naeem, in the West Bank. (Photo: © FAO/Marco Longari)

Seventy-five years after the mass displacement of Palestinians began, approximately 5.9 million registered Palestinian refugees live across the Middle East. Palestinians comprise the largest stateless community worldwide. While they constitute the world’s longest protracted refugee situation, their plight has been eclipsed by more recent displacement crises and dismissed as unsolvable.

Among refugees, this population is unique in several ways. For one, it includes people originally displaced from Palestine between 1946 and 1948, amid the creation of the state of Israel, as well as their children and other descendants; while these younger generations would not typically be considered refugees in other displacement situations, they are counted as such by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). So while the Palestinian refugee population has grown significantly over time, it has done so because of the descendants of people displaced decades ago, rather than new displacement. And unlike other refugees, Palestinians do not fall under the mandate of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), but instead are protected by UNRWA, which was established in December 1949 to provide them direct relief and other services. Unlike UNHCR, UNRWA cannot resettle refugees; it describes its mandate as to assist and protect Palestinians “pending a just and lasting solution to their plight.” UNRWA acts solely as a service provider, primarily for education, health (including mental health), social services, emergency assistance, and microfinance. It does not administer the refugee camps where approximately one-third of all Palestinian refugees live, which are the responsibility of the host country or governing authority.

This article provides an overview of the historical circumstances that gave birth to the displacement and dispossession of Palestinian refugees and takes stock of their current situation in countries across the Middle East, especially in light of worsening regional economies. While many long-term challenges are rooted in ongoing conflict involving Israel, other factors have contributed to Palestinian refugees’ situation, including the near impossibility of obtaining citizenship in many host countries and UNRWA’s precarious funding.

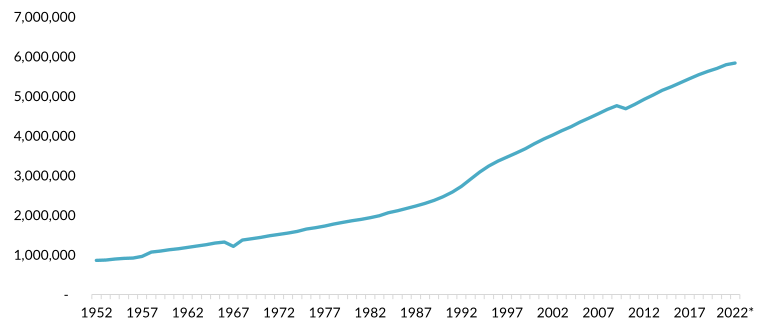

Figure 1. Number of Palestinian Refugees, 1952-2022*

* Data for 2022 are as of the middle of the year.

Note: Figure refers to Palestinians under the mandate of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA).

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Refugee Data Finder,” accessed April 27, 2023, available online.

The Creation of a Refugee Population

Colonialism set the stage for Palestinians’ dispossession. Following World War I, the League of Nations authorized the partition of the Ottoman Empire’s Middle Eastern territories by the United Kingdom and France. In the Palestine mandate, the United Kingdom was to foster a national home for Jewish people consistent with its 1917 Balfour Declaration, a goal aligned with those of the broader settler-colonial project of Zionism and opposed by Palestinian Arabs. Jews remained a minority in mandate Palestine, but their numbers increased during the 1930s as many fled Nazi persecution. Palestinian Arabs, who lacked institutional power, revolted from 1936 until 1939, leading British authorities to kill, wound, jail, or exile around one-tenth of all adult men. Following the revolt, the British government also set a limit on Jewish migration to the territory.

World War II brought cataclysmic changes. The horrors committed by Nazis and their collaborators in the Holocaust created a large displaced population, increasing pressure on British leaders to lift restrictions on Jewish migration to Palestine. Meanwhile, Zionist leaders shifted the focus of their diplomacy to the United States, where they enjoyed political and organizational support. President Harry Truman prevailed on Britain to resettle 100,000 Jewish refugees in Palestine, a proposal adopted by an Anglo-American Commission. The United Kingdom subsequently turned the question of Palestine over to the United Nations, whose Special Committee on Palestine proposed partitioning the mandate into Jewish and Arab states, with the city of Jerusalem as a separate entity. Despite their minority status, Jews were granted 55 percent of the mandate’s territory, including much of the productive agricultural land. With strong U.S. backing, the UN General Assembly adopted the partition measure on November 29, 1947.

In the civil war that erupted following the partition vote, Arab and Jewish forces clashed in anticipation of British withdrawal. Palestinian Arabs lacked the Zionists’ unity and resources and were reliant on an undersupplied Arab Liberation Army backed by regional states. In anticipation of an invasion, Jewish leaders instructed brigade commanders to empty cities and towns of presumably hostile Arab residents. Historians differ over the degree to which Zionist forces pursued ethnic cleansing as official policy, but the result was hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were expelled from their homes or fled. By the time David Ben-Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency Executive, proclaimed the establishment of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948, more than 300,000 Palestinian Arabs had been turned into refugees (although this predates the 1951 Refugee Convention, historical literature considers Palestinians who fled to have been refugees).

Israel’s establishment led to a new phase of fighting and an invasion of Palestinian territory by Arab states. Israel benefited from lack of unity among Arab countries. For instance, Zionists had previously held secret talks with King Abdullah of Transjordan envisioning his kingdom’s occupation of the geographically Arab portion of Palestine, a plan bitterly opposed by Abdullah’s rivals in the Palestinian leadership and other Arab states such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Despite UN mediation efforts, Israeli forces secured not only the area designated for the Jewish state under the partition plan but also territories such as the western Galilee and west Jerusalem. Israeli forces depopulated multiple Arab towns and villages. In all, more than 400,000 additional Palestinian Arabs fled or were driven from their homes during the war that followed Israel’s establishment.

Palestinians and other Arabs describe this dispossession as al-Nakba (“the disaster”). The term has come to refer not only to a discrete event, which is commemorated every year on May 15, but also to an ongoing process of dispossession. Despite UN General Assembly Resolution 194 calling for the right of refugees to return or be compensated for lost property, Israel prevented Palestinian refugees from returning and passed laws granting a state custodian authority over Palestinian lands. Hundreds of Palestinian villages were destroyed to prevent the return of their inhabitants and to facilitate Jewish immigration and settlement. The roughly 160,000 Arabs who remained in the territory that became Israel were citizens of the new country but nonetheless lived under a state of emergency and martial law until 1966.

Palestinian Displacement across the Middle East

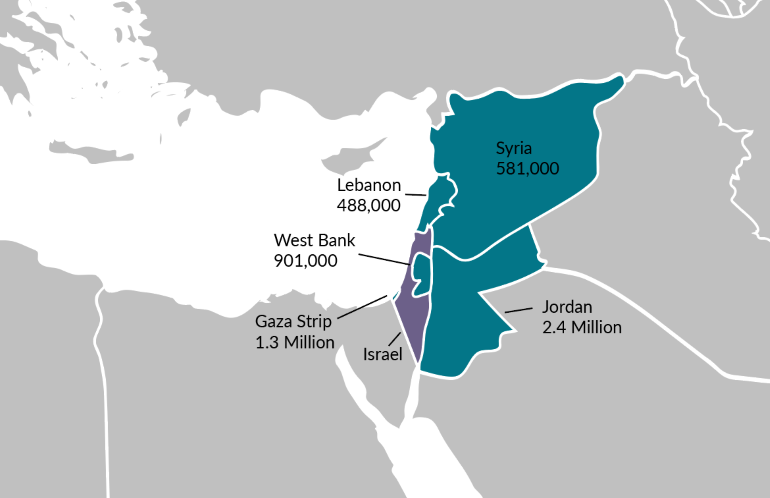

Palestinian refugees scattered across the region, and their population has grown several times over. As of 2022, 40 percent of the nearly 5.9 million registered Palestinian refugees lived in Jordan; 10 percent in Syria, although approximately one-fifth of these are believed to have fled to other countries since the start of the Syrian civil war; and 8 percent in Lebanon, according to UNRWA (see Figure 2). The remainder were in the Israeli-occupied territories of Gaza (26 percent) and the West Bank (15 percent).

Figure 2. Map of Palestinian Refugees, by Country of Residence, 2022

Note: Figure refers to Palestinians under the mandate of UNRWA.

Source: UNRWA, “UNRWA Registered Population Dashboard,” accessed April 14, 2023, available online.

Jordan: Host to the Largest Number of Palestinian Refugees

In 1949, Jordan welcomed approximately 900,000 refugees by amending the country’s 1928 Law of Nationality to grant equal citizenship to Palestinians; the 1954 Law of Jordanian Nationality later extended citizenship to Palestinians who arrived in Jordan after the 1949 addendum. Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1950, but the war in 1967 led to its loss of this territory and displaced between 250,000 and 300,000 Palestinians to the East Bank. Like those who had fled in 1948, Palestinians from the West Bank retained their Jordanian citizenship. However, Palestinians from Gaza displaced to Jordan after 1967 were not able to become Jordanian citizens. After 1988, when Jordan relinquished claims to the West Bank, the government also took steps to distinguish between so-called Palestinian-Jordanians and Transjordanians (or non-Palestinian Jordanians), and to push back against the Israeli narrative that Jordan could serve as an alternative homeland for Palestinians.

Because about three-quarters of Palestinians in Jordan are Jordanian citizens, they are fairly integrated into its society and economy, though Palestinians from Gaza remain barred from citizenship and are excluded from most rights and services, forced to turn to UNRWA for education and health care. Gazans also must renew their travel documents every two years, obtain special permits to work in the private sector, and pay double the tuition fees to access public schools and universities.

Palestinian refugees who had been living in Syria but later fled to Jordan after the Syrian civil war started in 2011—of whom there were more than 19,000 as of June 2022—also face challenges. Lacking Jordanian citizenship, they cannot work and access government services. And unlike other refugees from Syria, they are excluded from UNHCR assistance—which is more robust in acute displacement situations—and forced to instead turn to UNRWA. According to UNRWA, a trifecta of factors—the COVID-19 pandemic, increases in commodity prices, and the economic fallout of the Russia-Ukraine war—have recently exacerbated the impoverishment of Palestinian refugees from Syria, 80 percent of whom depended on UNRWA assistance as their main source of income as of 2022.

Lebanon: Life in Camps and Limited Rights

Unlike many of those in Jordan, the nearly 488,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon cannot become citizens and have very limited access to public health care, education, or the formal economy. While refugees' presence can be politically contentious everywhere, the permanent settlement of Palestinians in Lebanon (known as tawteen) evokes fears about upending the delicate balance of Lebanon’s confessional political system, which institutionalizes the division of power among religious communities. Historically, Lebanese politicians and many Palestinians have objected to anything thought to encourage tawteen. Until 2005, the Lebanese government prohibited Palestinian refugees from accessing the formal labor market, forcing them to work in the informal economy, where they received lower wages. Now, Palestinians born in Lebanon who have registered with UNRWA and the Ministry of Interior can obtain work permits and access 70 occupations.

Still, many challenges remain. Palestinians cannot access public health insurance and remain barred from numerous professions in the fields of law, engineering, and public health care. More alarmingly, approximately 210,000 Palestinians—close to 45 percent of the total Palestinian refugee population in the country—live in outdated camps where conditions tend to be poor.

In 1968, Palestinians obtained autonomous governance within camps in Lebanon under the Cairo Agreement. These camps had played a vital role as locations for political and military mobilization during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon and throughout the Lebanese civil war, and so their independence was reined in with the 1991 Taif agreement. Simultaneously, new laws prohibited Palestinians from residing outside camps or owning land or housing. Since then, the population in Lebanon’s Palestinian camps has grown, but the land allocated to them has remained practically the same, leading to overcrowding and unsafe construction. Recent economic and financial crises, impacts of the pandemic, and the Beirut Port explosion in August 2020 have fallen particularly hard on refugees in Lebanon; 93 percent of Palestinian refugees in the country lived in poverty as of 2022, according to UNRWA. The price of a food basket in refugee camps increased more than fivefold between October 2019 and July 2022, leaving many families unable to afford basic items.

Syria: New Displacement for Many amid Civil War and Natural Disaster

Syria meanwhile received a large number of Palestinian refugees in both the 1940s and the 1960s. Palestinians in Syria could not gain citizenship but otherwise could access employment, education, and health care on par with Syrian nationals. However, the civil war beginning in 2011 had a severe impact on Palestinian refugees. The camps of Dera’a, Yarmouk, and Ein el Tal—which combined hosted more than 30 percent of Palestinian refugees in the country—were nearly destroyed. About 120,000 Palestinians fled to other countries, meaning that about 438,000 of the 575,000 refugees who were registered with UNRWA remained in Syria as of 2022; of these, 40 percent were internally displaced.

Syria’s civil war has become localized over time, but the humanitarian situation remains dire and has been exacerbated by the economic downturn, declining agricultural production due to climate change, and health issues. Two earthquakes also hit Turkey and northwest Syria in February 2023, leaving tens of thousands dead and affecting Palestinian refugees in Aleppo, Latakia, and Hama in northern Syria. Close to 47,000 Palestinian refugees were affected and thousands were again displaced.

Refugees in Gaza and the West Bank

In addition to the 3.4 million registered Palestinian refugees living in host countries, nearly 2.5 million Palestinians live in the occupied territories of Gaza and the West Bank. Refugees comprise about 67 percent of Gaza’s population. They live in difficult socioeconomic conditions stemming from the land, air, and sea blockade imposed by Israel since 2007, when Hamas took political control of Gaza, as well as violence and political instability. As a result, 80 percent of the population depended on humanitarian assistance as of 2021. Poverty rates are extremely high (nearly 82 percent) and the unemployment rate is among the highest in the world, at nearly 47 percent as of August 2022.

The humanitarian situation in the West Bank is less severe, but Palestinian refugees nonetheless face numerous challenges such as Israeli-imposed closures and movement restrictions as well as conflict-related violence. Checkpoints and the unreliability of access to permits to enter and to work in Israel prevent many from accessing jobs, education, and health care, and can seriously impact their mental health. Israeli security forces frequently raid refugee camps in the West Bank—an average of 14 times per week as of October 2022, according to UNRWA—during which they have used tear gas, destroyed property, and harassed residents. Palestinians continue to be expelled from their homes in the West Bank, leading to further displacement. In 2022, 953 Palestinian-owned structures were demolished or seized across the West Bank, the most since 2016, and 1,031 individuals were displaced as a result.

Challenges for UNRWA

The UN General Assembly’s Resolution 194 (III) from 1948 set forth that Palestinians “wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their [neighbors] should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date,” which has been interpreted in international law as the right of return. This principle has had profound implications for the operations of UNRWA, which is seen as a temporary custodian of Palestinians in exile, as well as possible solutions to Palestinians' 75-year plight.

UNRWA is often thought of as a quasi-state, since it provides state-like services to Palestinians such as education, health care, and other assistance. Yet unlike a state that can collect taxes, UNRWA is almost entirely dependent on donor funding (which accounts for 93 percent of its budget), leading to chronic budget shortfalls and leaving it subject to political headwinds. Some argue that UNRWA’s mandate has grown too significant over time, making the organization financially unsustainable. Yet the number of Palestinians has grown significantly as additional generations have been born into statelessness. The United States has historically been UNRWA's top donor, contributing between U.S. $300-350 million per year, but under the Trump administration aid fell to U.S. $60 million in 2018 and was eliminated in 2019, before a restoration to U.S. $338 million in 2020. With the election of a Republican-controlled House of Representatives in 2022, UNRWA once again faces an uphill battle for funding, and agency staff fear that U.S. financial support could stop altogether if a Republican retakes the presidency in 2024.

The services and assistance UNRWA provides Palestinians are inextricably linked to the question of their return. Those arguing for defunding or dismantling the organization also often advocate for Palestinians to be absorbed into host societies. Yet most Palestinians lack full economic and social rights in these countries, and there is little appetite from either host-country politicians or Palestinians themselves to fully integrate, for fear that doing so means abandoning hope of return to their ancestral land. In addition to the repercussions for individual Palestinians, such a move would also be a profound shock to much of the Arab world, which has rallied around their cause for decades, despite a thaw in relations between some Arab governments and Israel via normalization agreements.

75 Years Gone, and What Next?

A resolution for Palestinian refugees would require a political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and refugees’ return to their ancestral lands or restitution for lost property. Such a solution has been debated for decades but seems dimmer than ever after the election of Israel’s far-right government in December 2022. Benjamin Netanyahu returned as prime minister after his party formed a coalition with parties regarded as extremist, generating the most right-wing government in the country’s history. Several members of the cabinet committed to strengthening the Israeli settler movement across the West Bank, despite findings that these settlements are illegal under international law, violate Palestinians’ human rights, and will lead to further Palestinian displacement. Minister of National Security Itamar Ben Gvir was previously convicted for inciting racism against Palestinians, and Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich has consistently called for expanding Israel’s territory and further expulsions of Palestinians. Violence rapidly escalated between Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank in 2023, including at the Jenin refugee camp, which Israeli forces raided in January, killing 10 Palestinians and wounding 20 more, including both militants and civilians.

Still, other reforms might be more attainable and could improve Palestinians’ access to services and increase opportunities for mobility. For one, although UNRWA does not have a mandate to resettle Palestinian refugees, the international community and receiving states could increase their use of complementary pathways such as existing work and study visa channels, in line with the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees. While historically many Palestinians—including political leaders—have feared resettlement would fragment and dilute their cause, Palestinians abroad can still retain their identity and need not concede the right to return. Increased opportunities for mobility are especially important for refugees in Gaza and the West Bank who have faced stringent barriers to exit from Israeli authorities.

For host societies, the lack of citizenship for many Palestinian refugees and other integration challenges are continual obstacles. Even without citizenship, legal changes allowing Palestinians to own land or seek employment in certain professions in Lebanon, for instance, could ultimately benefit both Palestinians and host-state societies and economies.

Finally, UNRWA’s dependance on individual donor countries is a major challenge. Some experts have suggested a shift to multiyear allocations rather than annual funding, which would allow UNRWA to better plan operations and reduce time spent on fundraising.

Seventy-five years into multigenerational and multicountry Palestinian displacement, soon no refugees will themselves have fled directly from their ancestral land before 1948. Instead, the international community has allowed generations of Palestinians to be born into refugee status, a fate shared by no other refugee group. This extraordinary position has transformed Palestinians into an emblem of wider geopolitical tensions but has failed to yield a meaningful resolution to their plight.

Sources

Amnesty International. N.d. Seventy+ Years of Suffocation. Accessed April 5, 2023. Available online.

Anera. 2022. Who Are Palestinian Refugees? Anera, August 19, 2022. Available online.

Berg, Kjersti G., Jørgen Jensehaugen, and Åge A. Tiltnes. 2022. UNRWA, Funding Crisis and the Way Forward. Bergen, Norway: Chr. Michelsen Institute. Available online.

Barron, Robert. 2023. For Israelis and Palestinians, a Tragic Spiral Reemerges. United States Institute of Peace commentary, February 1, 2023. Available online.

Erakat, Noura. 2019. Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Frost, Lillian. Forthcoming. Beyond Citizenship: Host State Relations with Protracted Refugees. In Forced Migration, Reception Policies and Settlement Strategies in Jordan, eds. Valentina Napolitano, Jalal Al Husseini, and Norig Neveu. London: I.B. Tauris.

Halabi, Zeina. 2004. Exclusion and Identity in Lebanon’s Palestinian Refugee Camps: A Story of Sustained Conflict. Environment and Urbanization 16 (2): 39-48. Available online.

Hourani, Albert. 2005. The Case against a Jewish State in Palestine: Albert Hourani’s Statement to the Anglo-American Commission. Journal of Palestine Studies 35: 80-90.

Human Rights Watch. 2022. Treatment and Rights in Arab Host States. Human Rights Watch, April 23, 2002. Available online.

Irfan, Anne. 2017. Rejecting Resettlement: The Case of the Palestinians. Forced Migration Review 54. Available online.

Janmyr, Maya. 2017. No Country of Asylum: ‘Legitimizing’ Lebanon’s Rejection of the 1951 Convention. International Journal of Refugee Law 29 (3): 438–65. Available online.

Khalidi, Rashid. 2020. The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Kurtzer-Ellenbogen, Lucy. 2023. What Does Israel’s New Government Mean for the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict? United States Institute of Peace commentary, January 5, 2023. Available online.

Morris, Benny. 2008. 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pappe, Ilan. 2006. A History of Modern Palestine. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rogan, Eugene L. and Avi Shlaim, eds. 2007. The War for Palestine. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shiblak, Abbas. 2006. Stateless Palestinians. Forced Migration Review 26: 8-9. Available online.

Shlaim, Avi. 1988. Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

UN Habitat. 2022. Palestinian Refugees Return to Their Homes in Refugee Camp in Syria after More than Ten Years. Press release, August 23, 2022. Available online.

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). 2023. West Bank Demolitions and Displacement | December 2022. New York: UNOCHA. Available online.

UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). 2022. Hitting Rock Bottom – Palestine Refugees in Lebanon Risk Their Lives in Search of Dignity. Press release, October 21, 2022. Available online.

---. 2022. Syria, Lebanon and Jordan 2022 Emergency Appeal Progress Report. Amman: UNRWA. Available online.

---. 2022. Where We Work: Syria. Updated August 2022. Available online.

---. 2023. Occupied Palestinian Territory Emergency Appeal 2023. Amman: UNRWA. Available online.

---. 2023. Syria, Lebanon and Jordan Emergency Appeal 2023. Amman: UNRWA. Available online.

---. 2023. Updated UNRWA Flash Appeal - Emergency and Early Recovery Response in Support of Palestine Refugees in Syria and Lebanon Affected by the Earthquakes and Aftershocks February - August 2023. Amman: UNRWA. Available online.

---. N.d. How We Are Funded. Accessed April 11, 2023. Available online.

Zhou, Yang-Yang, Guy Grossman, and Shuning Ge. 2023. Inclusive Refugee-Hosting Can Improve Local Development and Prevent Public Backlash. World Development 166: 106203. Available online.

Zurayq, Qustantin. 1956. Ma‘na al-Nakba. Beirut: Khayat.