You are here

Global Spending on Immigration Enforcement Is Higher than Ever and Rising

A double border wall leads to a boat launch in Yuma, Arizona. (Photo: Ariel G. Ruiz Soto)

The United States has in recent years spent more money on immigration enforcement than at any other point in history. For fiscal year (FY) 2024, the Biden administration has asked Congress for nearly $25 billion for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an increase of almost $800 million over the previous year and nearly equal to the entire gross domestic product (GDP) of Iceland. U.S. immigration enforcement budgets have been steadily increasing for many years, irrespective of the political orientation of the country’s federal government.

This is part of a worldwide trend, driven by the enforcement-first border and immigration policies of the Global North. The European Union's spending on border enforcement in 2023 was similarly at a record high, and border guard agency Frontex receives more money than any other single EU agency. While global spending for the sector is impossible to accurately measure, budgets for migration enforcement are on a consistent upwards slope.

Companies comprising the military and security industry are among the main beneficiaries of this spending bonanza. Building an ever more militarized and refined border infrastructure is a booming business, worth an estimated U.S. $48 billion in 2022 and on pace to grow to as much as U.S. $81 billion by 2030, according to market research agencies. Part of this growth will be driven by related industries such as biometrics and artificial intelligence, which are expected to be even larger sectors of which migration management is just one component.

This article provides an overview of spending on immigration enforcement in recent years, including on border activities and interior enforcement such as arresting and removing people found to lack authorization to remain in their country of residence. It focuses on the United States, the European Union, and Australia, which are among the top spenders in the sector; their budgets demonstrate the dramatic changes witnessed over the last three decades. While U.S. and EU budgets for immigration enforcement have risen steadily, Australia’s spending has been flatter due to the phasing out of its expensive and controversial offshore migrant detention system, among other reasons.

The Rise of Securitized Border Policies

Securitizing borders to stop irregular migration is not a new phenomenon, but only in recent decades has it risen to the top of the political agenda and budget calculations. There has been a steady upward trend in spending accompanying governments’ adoption of increasingly restrictive border policies and as they have expanded national and supranational border enforcement. With migration framed predominantly as a national security issue, irregular arrivals are often seen as threats that need to be countered with stronger enforcement, increasingly of a costly and militarized nature.

In 1986, the U.S. Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act in reaction to the increase in size of the unauthorized population from Mexico, placing more emphasis on border enforcement. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, homeland security—including border security—escalated as a priority in the United States and worldwide. In 2013, Migration Policy Institute (MPI) researchers concluded that “illegal immigration and enforcement have been the dominant concern driving immigration policymaking for more than 25 years.” With varying accents, this policy has further escalated since.

For the European Union, the 1995 establishment of the Schengen Area was a defining moment that coupled the opening of the bloc’s internal borders with robust control at its external boundary. Other events such as the war in the former Yugoslavia, the so-called Arab Spring of 2011, and in particular the European migration and refugee crisis of 2015-16 fueled politicized fears about waves of asylum seekers and other migrants coming to Europe, accelerating the process of border militarization and related spending.

In Australia, the increasing arrival of humanitarian migrants beginning in 2009 was picked up as an election issue. After a right-wing coalition formed a new government in 2013, leaders introduced Operation Sovereign Borders, a military-led patrol mission implementing a zero-tolerance policy for irregular maritime arrivals. In the following years, boats entering Australian waters were turned back and hundreds of people were transferred to offshore detention camps on Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

Box 1. Information Availability and Challenges

It is impossible to compile a complete overview of global border enforcement spending. Unlike military spending, which is largely covered by individual national defense budgets, border enforcement is often spread across multiple government agencies and departments, sometimes also at subnational levels. It can include spending on security and control at borders, on immigration enforcement within the interior of the country, detention and removal of those in the country without authorization, and border externalization efforts such as development cooperation and security assistance with migrant-origin and transit countries as part of a strategy to halt irregular migration. Moreover, as with other security policies, governments are not always transparent about their border control-related spending and may regard some elements of these budgets as classified.Trends in Spending

While it is impossible to calculate global border enforcement spending (see Box 1), it is possible to distinguish trends by looking at budgets for the major border agencies and funding instruments over the last decade.

United States

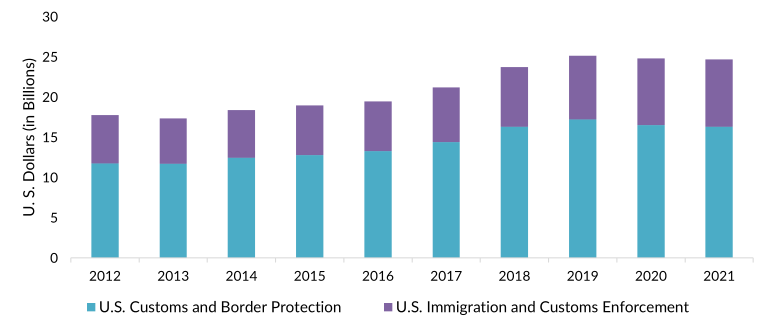

The budgets for both CBP and ICE—which are responsible for immigration enforcement at U.S. borders and in the interior, respectively—have increased virtually every year since FY 2012 (see Figure 1). The start of the Trump administration, with its emphasis on building a wall running the length of the nearly 2,000-mile border with Mexico and increasing use of detention, lifted the budget considerably. Under the Biden administration, wall construction has largely been de-emphasized and the government has shifted to other forms of border control, including so-called smart borders. The administration’s FY 2024 budget request for CBP, for example, includes $535 million for new border security technologies at and between ports of entry.

Figure 1. Budgets of U.S. Customs and Border Protection and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, FY 2012-21

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) analysis based on Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Budget-in-Brief documents, available online.

U.S. border enforcement spending is not just a federal matter. Texas, for example, spent about $4 billion on border enforcement in 2021 and 2022 for Operation Lone Star, which included funding for the state’s own border wall and to bus thousands of migrants from border towns to Democrat-led cities in the U.S. interior.

European Union

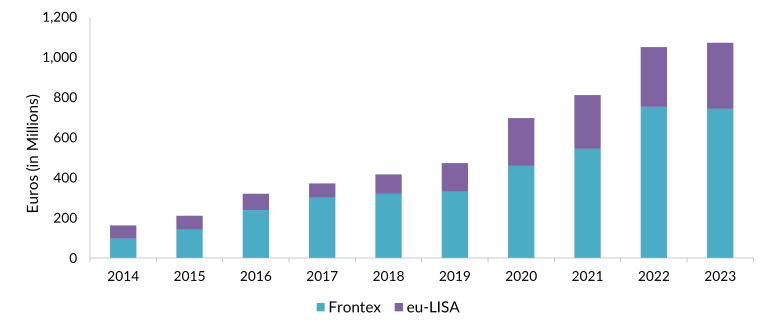

Since its establishment in 2005, the EU border guard agency Frontex has seen increasing budgets, especially since 2015. As of this writing, it had the highest budget of all EU agencies: 5.6 billion euros for the 2021-27 budget cycle. However, the 2023 budget of 744 million euros was lower than the original proposal (794 million euros), in response to ongoing concerns about Frontex's role in pushbacks of asylum seekers and other migrants crossing the Mediterranean.

In general, the agency’s growing budget has accompanied the expansion of its mandate and operational areas, including the ability to buy or lease border security equipment, the building of a 10,000-person-strong border police force, assumption of a central role in EU forced returns, and the start of operations in non-EU Member States. Meanwhile, eu-LISA, the agency that beginning in December 2012 has operated large-scale information technology systems for border enforcement (mainly biometrics databases), has also seen rapidly increasing budgets in line with the expansion of these databases and an effort to make them interoperable.

Figure 2. Budgets of Frontex and eu-LISA, 2014-23

Sources: Author’s analysis of EU annual budgets, available online.

The European Union also funds some border security efforts for its Member States. The main instrument for this in the current budget cycle is the Integrated Border Management Fund, with a nearly 7.3-billion-euro budget for 2021-27. This is much larger than its predecessors, the External Borders Fund (1.7 billion euros for the 2007-13 period) and the Internal Security Fund – Borders (nearly 2.8 billion euros for 2014-20).

Australia

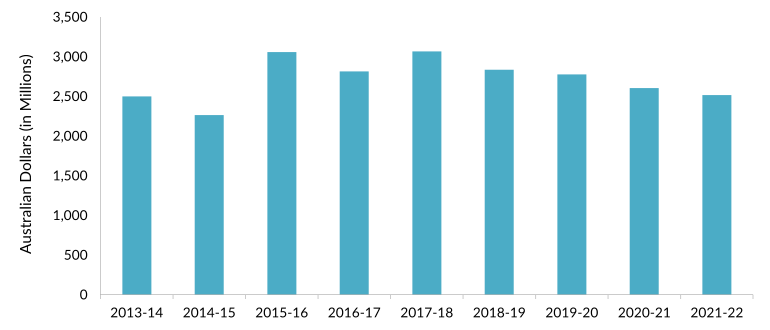

Australia's national budget is divided along program lines instead of agencies, which makes it difficult to compare individual years. Nonetheless, the budget for border enforcement aspects of the Australian Border Force has remained about the same or shown a small decline in recent years, unlike for counterparts in the United States and the European Union. The Border Force did get a boost after 2013, mainly because of the purchase of a fleet of patrol boats between 2013 and 2015. A second purchase of boats, also meant for border security, was carried out by the Navy and hence does not appear in the Border Force’s budget.

While Australia's controversial offshore migrant detention system was very expensive—amounting to A$12.1 billion since 2013—it is now in the last part of phasing out. In coming years, Australia plans to spend billions on its Future Maritime Surveillance Capability project, including an investment of up to A$1.3 billion in a new drone development program.

Figure 3. Australian Government Border Enforcement Spending, FY 2013-22

Source: Author’s analysis of Australian Department of Home Affairs annual reports, available online.

Spending Abroad

These data provide only a snapshot of total spending by these governments on efforts to limit spontaneous migration. The figures do not include assistance for other countries’ migration management, for example, which has become an increasing focus as top migration-destination governments seek to externalize border control by recruiting transit countries to assist with halting irregular migration before it arrives. On the whole, European border enforcement spending from 2014 to 2016 amounted to at least 1.7 billion euros for measures within the continent and 15.3 billion euros for migration-related efforts beyond the continent, according to the Overseas Development Institute. Of the European Union’s 80-billion-euro Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI)—its main development cooperation tool—10 percent has been dedicated to supporting recipients’ migration management and governance.

Partly because of these efforts, many countries outside the Global North have increased their migration enforcement spending or at least kept it stable. While no comprehensive figures are available, forecasts by market research companies often predict an annual market growth of around 7 percent for border security by 2028. This is slightly higher than the year-over-year increase in the last few years, which the firm Technavio has estimated at just under 7 percent as of 2023. Some parts of the border enforcement market can expect much higher growth, such as aspects related to automated border control and biometric technologies, in which the development and refining of new technologies and applications has spurred government programs with increasing budgets.

Major Benefits for Companies

For governments worldwide, enforcement spending has occurred through purchases of equipment such as helicopters and patrol vessels as well as radar, night vision equipment, drones, and other monitoring technologies. Other common spending areas include recruitment of personnel and costs associated with detention and deportation. A sizable amount of money is spent on outsourcing operations to companies that operate detention centers, perform surveillance, and provide audit and consultancy services, among other areas.

The security industry has been a main beneficiary of these policies. Mirroring the leading role played by Western countries in boosting migration control as a topic of global concern, firms based in Australia, Europe, Israel, and the United States are the most important corporate players in this field. Among them are some of the world's major arms-producing companies, such as Airbus, Elbit Systems, Leonardo, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Thales.

Some companies are big players in specific niches of the border security and control industry. For instance, the Spanish firm European Security Fencing was long the sole provider of concertina razor wire used for border walls and fences across Europe. Dutch shipbuilder Damen has provided border patrol vessels to the United Kingdom as well as many Mediterranean countries—including Libya and Turkey. In the United States, GEO Group and CoreCivic run private detention centers, including for immigration purposes.

Compared to the global defense market, which rose to U.S. $2.2 trillion in 2022, the border security field remains quite small, at about $48 billion. However, military contractors often consider migration-related business important for their bottom line. For one, it offers an opportunity to diversify their portfolios—an important strategy amid a temporary decline in global military spending post-Cold War. Companies and governments also regularly use borders as testing grounds for new security technologies since migration control may be less likely to stir controversy.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted countries particularly in Europe to increase military spending, but it remains to be seen how this development will influence the border security industry. Large companies may shift attention to their core military business, or they may decide to keep border and other security markets as important components of their operations.

Industry Lobbying

Corporations have played an active role in shaping border and migration policies. Lobbyists and other industry officials regularly meet with policymakers and authorities, join official government advisory committees, publish influential proposals, and showcase their work at fairs and conferences around the world. Research has shown, for example, an increasing closeness between Frontex and the military and security industry in the European Union in recent years, where Frontex's growing budget to purchase or lease its own border security equipment has led to an expanding dialogue with corporations. Large companies also have regular meetings with the European Commission. In the United States and Australia, campaign contributions and other financial support for political candidates are also an important means by which companies can influence lawmakers. During the 2020 campaign, U.S. candidates in both parties were supported by more than U.S. $40 million in contributions from political action committees and individuals associated with companies active in border enforcement.

Industry lobbyists tend to push the security narrative, as described above, to secure militarized migration policies, increased use of autonomous systems and artificial intelligence (AI), and bigger enforcement budgets. At times, governments and border authorities seem to treat company representatives as policymaking partners rather than profit-driven contractors. In some instances, such as the 2015 EU regulation expanding Frontex’s mandate, government policies have reflected industry proposals.

Consequences and Future Developments

Experts have pointed to the negative consequences that increased securitization of migration have for people on the move. Rather than halting irregular migration, border militarization often diverts migrants to other crossing points, particularly more dangerous ones, while making them more dependent on smuggling and increasing migration costs. Irregular migration routes across the Mediterranean and at the U.S.-Mexico border are amongst the deadliest in the world; in 2022, more than 3,000 migrants were recorded as having died or going missing along these routes, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Moreover, the number of displaced persons globally has steadily increased over the years, suggesting that the push factors for migration are rising concurrent with enforcement budgets. There were more than 42 million refugees and asylum seekers worldwide as of 2022, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The global increase in migration enforcement has been predominantly driven by the continuous push for ever-more-secure borders, in response to narratives that unauthorized migration is by and large a security threat. There are no indications that this will change in the near future.

Sources

Akkerman, Mark. 2019. The Business of Building Walls. Amsterdam: The Transnational Institute (TNI), Stop Wapenhandel, and Centre Delàs. Available online.

---. 2021. Financing Border Wars: The Border Industry, Its Financiers and Human Rights. Amsterdam: TNI and Stop Wapenhandel. Available online.

American Immigration Council. 2021. The Cost of Immigration Enforcement and Border Security. Washington, DC: American Immigration Council. Available online.

Australian Department of Home Affairs. 2018. Securing Australia's Borders for the Future. Press release, October 29, 2018. Available online.

Cosgrave, John et al. 2016. Europe's Refugees and Migrants: Hidden Flows, Tightened Borders and Spiralling Costs. London: Overseas Development Institute. Available online.

de Haas, Hein. 2015. Don't Blame the Smugglers: The Real Migration Industry. World Bank blog post, September 24, 2015. Available online.

Douo, Myriam, Luisa Izuzquiza, and Margarida Silva. 2021. Lobbying Fortress Europe: The Making of a Border-Industrial Complex. Corporate Europe Observatory, February 5, 2021. Available online.

Jones, Chris, Jane Kilpatrick, and Yasha Maccanico. 2022. At What Cost: Funding the EU's Security, Defence, and Border Policies, 2021-2027. Amsterdam: Statewatch and TNI. Available online.

Meissner, Doris, Donald M. Kerwin, Muzaffar Chishti, and Claire Bergeron. 2013. Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Miller, Todd and Nick Buxton. 2021. Biden's Border: The Industry, the Democrats and the 2020 Elections. Amsterdam: TNI, Mijente, and American Friends Service Committee. Available online.

Miller, Todd, Nick Buxton, and Mark Akkerman. 2021. Global Climate Wall: How the World’s Wealthiest Nations Prioritise Borders over Climate Action. Amsterdam: TNI. Available online.

Refugee Council of Australia. 2023. Offshore Processing Statistics. March 7, 2023. Available online.

Technavio. 2022. Border Security Market by Platform, Component, and Geography - Forecast and Analysis - 2023-2027. N.p.: Technavio. Available online.

Vantage Market Research. 2022. Border Security Systems Market - Global Industry Assessment & Forecast – 2023-2030. N.p.: Vantage Market Research. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. UNHCR: Ukraine, Other Conflicts Push Forcibly Displaced Total Over 100 Million for First Time. Press release, May 23, 2022. Available online.

White House. 2023. Fact Sheet: President Biden’s Budget Strengthens Border Security, Enhances Legal Pathways, and Provides Resources to Enforce Our Immigration Laws. White House fact sheet, March 9, 2023. Available online.