You are here

Amid an Unfolding Humanitarian Crisis in Syria, the European Union Faces the Perils of Devolving Migration Management to Turkey

Turkish and EU flags (Photo: Ian Usher )

Facing escalations in violence and unprecedented levels of displacement in northern Syria’s Idlib province, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has upended the unstable EU-Turkey agreement, using the threat of refugees and migrants pouring into Europe as leverage to gain support from Brussels in response to the unfolding humanitarian crisis. After years of threatening to “open the gates” between Turkey and Europe, the Turkish government introduced overnight an open-door policy in late February 2020, encouraging tens of thousands of asylum seekers and other migrants in Turkey to head towards European borders.

The immediate result was stark scenes of violence at the Greek-Turkish border, with thousands of migrants pushed back by Greek police and military patrols with tear gas, water cannons, and stun grenades. There were also reports of individual asylum seekers being detained, assaulted, robbed, stripped, and forced back across the border. This chaos culminated in a meeting March 17 between Erdoğan and European leaders to renegotiate the EU-Turkey agreement, one of the key factors that curbed the mass movement of refugees and migrants to Europe witnessed in 2015 and 2016.

Under terms of the 2016 agreement, EU leaders promised billions of euros in economic support, visa liberalization, and increased resettlement of Syrian refugees in exchange for Turkey’s agreement to prevent the onward movement of migrants across the Aegean to the Greek islands. Erdoğan has complained bitterly that Europe has not upheld its end of the bargain, including a lack of movement on reviving Turkey’s stalled EU accession bid, updating its customs union with the European Union, allowing Turks to visit the bloc without visas, and not delivering on all the promised funds. While he threatened to keep allowing migrants to reach European borders until his demands were met, there were signs in mid-March that Turkey was winding down its open-door policy.

European leaders have demonstrated their interest in keeping the deal alive. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President Charles Michel met in Brussels on March 9 with Erdoğan, with von der Leyen pledging to “fill in the missing pieces” originally pledged. A week later, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, French President Emmanuel Macron, and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson confirmed their commitment to the EU-Turkey agreement during a videoconference with Erdoğan, with Merkel saying she was willing to increase EU funds to help care for Syrians who have sought refuge in Turkey. Macron also pledged a further 50 million euros for the refugees in Turkey and Syria’s Idlib province, the scene of the recent fighting by Syrian government forces and its Russian ally. The leaders also discussed ways in which to combat the Russian threat inside Syria, as well as the risk of coronavirus (COVID-19) spreading to refugee camps bordering Syria, including those in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey.

This article examines the reasons behind the recent tensions surrounding the EU-Turkey deal, the broader EU approach to working with third countries to achieve migration management objectives, and recent refugee policies that may be a violation of the spirit of the international humanitarian and refugee law and conventions to which Turkey and the European Union are signatories.

Pushing Borders Out

The asylum seekers and other migrants recently massed at the Greek-Turkish border are at the center of a high-stakes political and diplomatic battle, in which Erdoğan is seeking NATO support and the enforcement of a no-fly zone after escalating military tensions in Syria. He also wants additional relief as his country hosts well more than half of the 5.6 million Syrians who have fled their war-torn country.

The plight of refugees and migrants on both sides of the border are also the visible result of the European Union’s decision to outsource its external border management to third countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region, including Libya, Morocco, and Egypt. After the relative success of the EU-Turkey deal, the European Union in mid-2016 announced a mix of financial and logistical support to countries including Mali, Niger, Jordan, and Senegal under the Migration Partnerships Framework. In 2017, the Malta Declaration included a series of EU interventions in Libya, offering support to local authorities and other groups there in exchange for reducing the number of migrants setting off from the Libyan coast across the Mediterranean. Similarly, the European Union granted 60 million euros to Egypt for a program meant to curb irregular migration to Europe. These deals have prompted widespread criticism that EU leaders are offshoring their responsibilities to governments that have starkly different views of human rights, resulting in the mistreatment and, in some cases, detention or deaths of migrants.

Tensions Surrounding the EU-Turkey Deal

The EU-Turkey Statement and Action Plan inked in 2016, which pledged 6.6 billion euros worth of resources to help Turkey cope with its heavy humanitarian burden, falls short of the global, multilateral solution needed to resolve the Syrian conflict, of which mass Syrian displacement across the Turkish border is one byproduct.

Erdoğan’s abrupt decision in February to open the doors and allow asylum seekers to reach the Greek border—in some cases via officially organized buses—came after dozens of Turkish troops were killed in a surprise airstrike by the Syrian government, and hundreds of thousands of Syrians were newly displaced to the Syrian-Turkish border due to the escalating violence. Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Turkey has taken in more than 3.6 million refugees from Syria and has cited the impossibility of accepting more. However, since December 2019, more than 1 million Syrian civilians in Idlib province have been systematically displaced northward as the Syrian government and its Russian ally attempt to capture the last armed opposition stronghold. This has resulted in devastating conditions and mounting pressure along the Syrian-Turkish border, as hundreds of thousands of people are landlocked between the impending military offensive and the closed Turkish border. Turkey has felt particularly alone in its response to protect its borders from the Syrian government offensive, as well as mitigating the flood of Syrian civilians fleeing the violence.

As a result, Turkey’s decision to break its agreement with the European Union and permit onward movement has led to the arrival at the Greek border in recent weeks of tens of thousands of hopeful refugees from Syria and Afghanistan, as well as migrants from Bangladesh, Iran, Morocco, Pakistan, South Sudan, and various East African countries. The result incited fear of a repeat of the 2015-16 flows, when Europe received more than 2 million asylum seekers and other migrants, resulting in a defensive and reactionary response from EU leaders and ill will regarding upended policies and agreements.

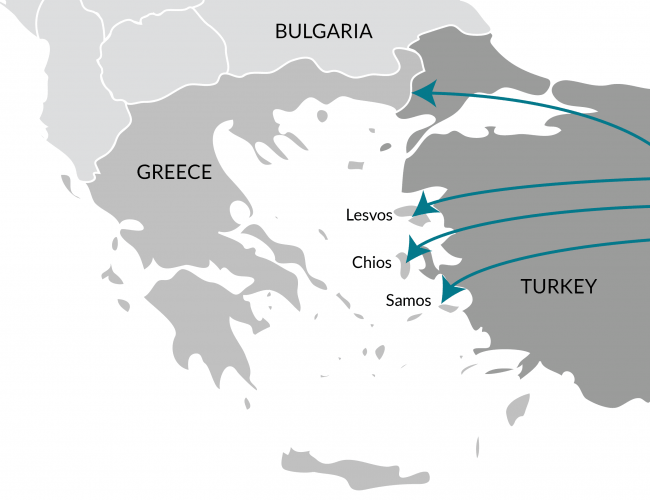

Figure 1. Key Routes through Turkey to Greece

Turkey has openly accused Europe and the international community at large of not sharing the burden of the Syrian crisis. "After we opened the doors, there were multiple calls saying, 'Close the doors’," Erdoğan said in a televised address. "I told them, 'It's done. It's finished. The doors are now open.' ... Hundreds of thousands have crossed, soon it will be millions."

A Retrenchment from Long-Held European Values?

The European response has been nothing less than stringent. One migrant who arrived at the Greek border said, “We were expecting compassion, but the Greeks are treating us like animals.” Photos and videos have emerged of Greek officials taking forceful action against recent arrivals, including the deliberate capsizing of boats holding men, women, and children. And Greece suspended asylum applications for a month, saying it had prevented more than 42,000 migrants from entering the European Union illegally over a two-week period.

EU-wide fears of a repeat of the 2015-16 crisis have resulted in a hardened stance by politicians across the political spectrum, with significant support for Greece’s actions to repel unauthorized arrivals. During a recent visit to Greece, von der Leyen praised the country as “Europe’s shield” and emphasized the shared responsibility of all EU countries to protect Europe’s external borders. The European Union pledged 700 million euros in aid to Greece and the deployment of a Frontex rapid border intervention team that would offer aircraft, patrol vessels, and 100 border guards to assist Greek authorities.

By repelling asylum seekers at the Greek and Bulgarian borders, European leaders are using drastic measures beyond anything that has been done to date; these actions may violate human rights and refugee law outlined in the UN Geneva Convention on Refugees. “Neither the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees nor EU refugee law provides any legal basis for the suspension of the reception of asylum applications,” the UN High Commissioner for Refugees said in response to Greece’s decision to suspend asylum applications.

Pivoting from the Fragile EU-Turkey Deal

The reactionary approach by the EU and the lack of preparedness for the worst-case scenario incited by Turkey has demonstrated the fragility of agreements put in place with third countries to stem unwanted migration to Europe.

A spokesman for the EU executive said that the bloc had no advance warning that Turkey’s open-door policy about-face was coming. "I would like to stress that there was no official announcement from the Turkish side about any changes in their asylum seeker, refugee or migrant policy," the official told a news briefing, demonstrating the gap in communication and coordination between Ankara and Brussels in the days leading up to Turkey’s surprise action.

The European Union and its Member States now find themselves in the same place they were in the thick of the 2015 crisis: with a Common European Asylum System (CEAS) badly in need of reform, and with some migration management offshored to partners that can use the deals as leverage at pivotal moments. In addition, the threat of COVID-19 spreading within and across European borders has also led to more severe mobility-limiting measures. On March 18, Germany closed its borders to all non-EU citizens, including refugees, placing a temporary hold on an informal resettlement program with Turkey. Humanitarian activists are warning that the pandemic is lessening support for refugees and migrants across Europe. They also are raising fears about the health and wellbeing of refugees in crowded camps, in particular young and unaccompanied children. In the absence of consensus among EU Member States on how to equitably share responsibility for asylum seekers, the Greek islands have been used as holding centers, leaving refugees and other migrants in often inhumane conditions.

On a global scale, these unprecedented events not only demonstrate the fragility of the EU-Turkey deal, but also the overall shortcomings of the international refugee response. Turkey, which has carried the burden of a massive humanitarian response with limited international solidarity, engaged in a risky strategy by acting out against the European Union. The brinksmanship has showcased the limited capacity the international community has in mitigating the use of vulnerable populations as leverage for political and diplomatic battles between countries. It also has served as a stark reminder that durable refugee solutions—including resettlement from countries of first asylum—remain options for only a tiny fraction of those who are displaced. Finally, the unyielding displacement from Syria as a result of an endless conflict represents only the latest evidence of the need for a more comprehensive solution to address the root causes of human suffering on Europe’s frontiers.

Sources

Agence France Presse. 2020. Erdogan Warns Europe It Will Have to Share Migrant “Burden.” Agence France Presse, March 2, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Germany Halts Refugee Program with Turkey to Combat Coronavirus. Agence France Presse, March 18, 2020. Available online.

BBC News. 2020. Greece Suspends Asylum Applications as Migrants Seek to Leave Turkey. BBC News, March 1, 2020. Available online.

Collett, Elizabeth. 2018. Turkey-Style Deals Will Not Solve the Next EU Migration Crisis. Migration Policy Institute commentary, March 2018. Available online.

Daragahi, Bourzou. 2020. Coastguard Seen Apparently Trying to Capsize Boat Full of Refugees Before Attacking Them with Stick, as Child Drowns Off Coast. The Independent, March 2, 2020. Available online.

Deutsche Welle. 2020. Syrian Airstrikes Kill Dozens of Turkish Troops in Idlib—As It Happened. Deutsche Welle, February 28, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Erdogan Warns ‘Millions’ of Refugees Heading to Europe. Deutsche Welle, March 2, 2020. Available online.

---. EU-Turkey Migrant Deal Still Intact, Germany’s Merkel Says. Deutsche Welle, March 17, 2020. Available online.

European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies. 2015. EU Cooperation with Third Countries in the Field of Migration. Brussels: European Union. Available online.

---. 2019. Legislative Train Schedule Towards a New Policy on Migration: EU-Turkey Statement and Action Plan. Last updated September 20, 2019. Available online.

Jamieson, Alastair, Kirsten Ripper, and Alasdair Sandford. 2020. Greece Is “Europe’s Shield” in Migrant Crisis, Says EU Chief von der Leyen on Visit to Turkey Border. Euronews, March 4, 2020. Available online.

Kampouris, Nick. EU Vows to Revive 2016 Migrant Deal with Turkey. Greek Reporter, March 10, 2020. Available online.

Kelly, Annie, Harriet Grant, and Lorenzo Tondo. 2020. NGOs Raise Alarm as Coronavirus Strips Support from EU Refugees. The Guardian, March 18, 2020. Available online.

Reuters. 2020. Turkey’s President Accuses Greece of Using ‘Nazi’ Tactics to Turn Away Asylum Seekers. Reuters, March 12, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. EU Says Expects Turkey to Uphold Commitments on Migrant Flows. Reuters, February 28, 2020. Available online.

Rothwell, James. 2020. France Announces Further €50m for Syrian Refugees amid Turkey Tensions. The Telegraph, March 17, 2020. Available online.

Stevis-Gridneff, Matina and Patrick Kingsley. 2020. Turkey Steps Back from Confrontation at Greek Border. The New York Times, March 13, 2020. Available online.

Tsourapas, Gerasimos. 2018. Egypt: Migration and Diaspora Politics in an Emerging Transit Country. Migration Information Source, August 8, 2018. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. UNHCR Statement on the Situation at the Turkey-EU Border. Press release, March 2, 2020. Available online.