You are here

Bangladesh’s Economic Vitality Owes in Part to Migration and Remittances

A returned migrant with his family in Bangladesh. (Photo: IOM)

Bangladesh has a long and complex history of migration. Over the last century, the country split from India and then Pakistan, each moment of independence corresponding with a rush of migration into and out of its territory. Amid sustained economic growth and rising living standards after Bangladesh declared its independence in 1971, labor migration—particularly to the Middle East—has grown in recent decades, due in part to an unstable domestic labor market. Emigration is largely the result of economic and social drivers, while natural disasters and environmental insecurity have accelerated internal migration; given its largely delta geography, most of the country is less than five meters (16.5 feet) above sea level. Bangladesh’s population density is also among the world’s highest, with 1,301 people per square kilometer (approximately 3,370 people per square mile) in 2021, according to UN estimates, nearly triple the density of neighboring India.

In This Article

-

Bangladesh's migration history can be divided into five phases

-

Most Bangladeshi migrants work in low- or semi-skilled sectors

-

Poverty has been gradually falling on the back of sustained economic growth

-

Remittances have been among the most powerful tools in Bangladesh’s economic outlook

-

The country will likely remain an origin for labor migrants for years

Since independence, emigration has been instrumental for improving the standard of living and social status of residents in Bangladesh, a country of 171 million people. Millions have taken short-term contracts abroad, with a record 1.3 million leaving in 2023 alone. In addition, an unknown but large number of Bangladeshis have taken unofficial overseas contracts that are not registered with the government. The nature of labor migration from Bangladesh is mainly short-term, based on unskilled or semi-skilled work. More than 7.4 million Bangladesh-born individuals lived abroad as of 2020, according to UN estimates.

The money these migrants and others send back—$21.9 billion via official remittance channels in 2023, according to the government—is a major source of development for Bangladesh. Aside from India, Saudi Arabia has long ranked as the largest origin of official remittances to Bangladesh, accounting for $4.1 billion in 2022, followed by other Gulf countries. Most Bangladeshi emigrants are men, although more women have been leaving, particularly to go to the Middle East and East Asia. However, they do not always secure a stable income or safe residence; many have been victims of torture and violence, including sexual exploitation, and have returned to Bangladesh.

The foreign-born population has grown dramatically since 2015, due to the influx of forcibly displaced Rohingya from Myanmar (also known as Burma); there were nearly 1 million Rohingya in Bangladesh at this writing. Other foreign nationals are drawn to the technology and construction sectors, as well as the garment sector. Still, while there were approximately 2.1 million immigrants overall in Bangladesh as of 2020, according to UN estimates, net migration has generally declined in recent years and stood at a rate of minus 2 per 1,000 people as of 2024.

This country profile reviews migration trends from and to Bangladesh and the impact of emigration, particularly using remittances as an indicator of the developmental potential of migration. It focuses chiefly on the period since the country’s independence from Pakistan.

The territory that was once a part of the British colony of India and after the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 became known as East Pakistan was recognized as an independent country on December 16, 1971. The migration history of what is now the People’s Republic of Bangladesh is divided into five important phases.

In the precolonial era, there is ample historical evidence that the region once known as East Bengal experienced frequent international and internal migration, which helped make it famous for tea cultivation. In a second phase, during the British colonial period (1858-1947), many people especially from Bangladesh’s northeastern Sylhet district moved to England and worked in British shipyards and other sectors. A third phase occurred amid the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947. As many as 20 million people moved between and within both countries, with religion often a motivating factor; many Muslim people left India and settled in Pakistan, while Hindus went in the opposite direction.

The nine-month 1971 war of independence triggered Bangladesh’s fourth phase of migration, with approximately 10 million people displaced from Bangladesh across the Indian border, many of whom—particularly Hindus—did not return afterwards. Moreover, many people living in Pakistan since 1971 have been unable to return to their native Bangladesh, while people in Bangladesh with Pakistani roots, called Biharis, have sought to be repatriated to Pakistan.

The current and fifth phase began after independence. Bangladesh’s fragile economy had limited job opportunities, resulting in large numbers of semi-skilled and unskilled male workers moving temporarily for employment in the Middle East, particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Many of these patterns began in 1973, when oil prices rose and several Gulf countries had a rapid demand for new infrastructure. The heterodox migration process continues to this day, even as the world’s eighth most populous country has been touted as a model of development and an economic miracle, in part because of the reliance on exports as a driver of domestic growth.

Current Migration Trends and Characteristics

Currently, Bangladesh is primarily a country of migrant origin, although it has also recently become home to a growing number of immigrants, especially refugees from Myanmar. Studies show that economic factors, social considerations, and the policy context in Bangladesh and destination countries are key drivers of migration, although family and cultural forces also have a significant impact. Moreover, higher standards of living are a strong pull factor, especially to countries in Europe and North America.

Although most Bangladeshi migrants work in low- or semi-skilled sectors abroad, they are driven in part by a mismatch between Bangladesh’s educational offerings and job prospects. As a result of a massive increase in educational institutions in Bangladesh, the number of educated people has risen, including in rural areas, yet there are not sufficient employment opportunities for them. Much of the economy relies on agriculture and the booming garment sector. And due to factors such as economic insecurity, depressed wages, and the absence of a robust social safety net, there is a growing interest among the educated population in emigrating rather than local entrepreneurship. Environmental vulnerability also contributes to the drivers of migration, especially when combined with poverty and poor labor market conditions, providing a strong impetus for seeking work abroad.

Emigration for Employment

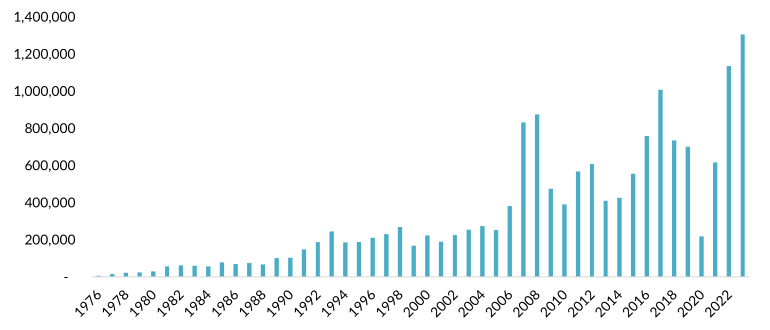

Bangladesh is the sixth largest migrant-sending country globally, and the eighth largest remittance-receiving country, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). According to Bangladesh government statistics, workers have taken nearly 16.1 million short-term labor contracts in 164 countries around the world from 1976 through 2023, with the overwhelming majority in the Persian Gulf (see Figure 1). Some may have returned to Bangladesh after their contract ended; others were forced to return for a variety of reasons, such as unsuccessful health tests or poor job performance. Moreover, some migrants die while abroad—including more than 1,000 Bangladeshis who reportedly died in Qatar during the decade-long build-up to the 2022 FIFA World Cup. And many return after their contract ends.

Figure 1. Departures from Bangladesh for Overseas Employment, 1976-2023

Notes: Figure shows new overseas employment and numbers are not cumulative. Data do not include unofficial employment contracts that are not registered with the government.

Source: Bangladesh Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET), “Foreign Employment and Remittances from 1976 to 2023,” updated January 27, 2024, available online.

Of the more than 7.4 million Bangladeshi migrants abroad as of 2020, approximately 1.3 million were in Saudi Arabia, 1.1 million in the United Arab Emirates, and 380,000 in Kuwait, with smaller numbers elsewhere in the region, according to UN statistics.

Migration has been increasing to other Asian countries such as Malaysia (home to 416,000 Bangladeshis as of 2020), Singapore (80,000), and South Korea (12,000). Nearly 2.5 million Bangladeshis are believed to live in neighboring India, many likely without authorization. Irregular migration between the two countries is a controversial topic given their history.

Immigration

A significant number of foreign born in Bangladesh are Rohingya Muslims who were forcibly displaced from their native Myanmar as part of a government campaign that multiple organizations and governments have termed a genocide and ethnic cleansing. Rohingya have been living as refugees in various countries including Bangladesh since 1978; episodes of violence occurred in the early 1990s and in larger numbers since 2015. As of March 2024, more than 978,000 Rohingya lived as refugees in Bangladesh’s southeastern Cox’s Bazar district, mainly in the Ukhia and Teknaf subdistricts, where the Kutupalong refugee camp is believed to be the world’s largest. Since 2021, approximately 34,000 Rohingya have been relocated to a low-lying island in the Bay of Bengal called Bhasan Char in order to reduce stress in Cox’s Bazar. Advocates have criticized the Bhasan Char location, noting those on the island could be at serious risk during monsoon season because of inadequate storm and flood protection. Bangladesh is the largest destination country for Rohingya and other people fleeing Myanmar; more than 320,000 Rohingya and other Burmese refugees lived in Malaysia, Thailand, and India as of mid-2023, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Figure 2. Map of Bangladesh

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) artist rendering.

The Bihari Muslim minority, also known as trapped Pakistanis, is another major immigrant group in Bangladesh. Although many Biharis have assimilated into the local population, some have migrated to Pakistan and others have settled in refugee camps across Bangladesh. Since 2008, Biharis have been able to obtain citizenship in Bangladesh, yet many have face challenges and discrimination. At least 250,000 Biharis have been estimated to live in urban areas of Bangladesh in recent years, many in slums. The largest is in the Mohammadpur area of Dhaka, in a place known as Geneva Camp, where more than 25,000 people lived as of 2021.

Among the non-humanitarian immigrant population, there are many Asians, including Malaysians (200,000 as of 2020) and people from China (160,000), Indonesia (150,000), Laos (86,000), and India (34,000). There are no reliable estimates on irregular migrants in Bangladesh, although the number of people who pay fines for violating immigration laws are often from high-income countries in Europe and North America, as well as Australia.

Internal Migration and Displacement

Internal migration in Bangladesh has been increasing rapidly, especially from rural villages to urban areas such as in and around Dhaka. Interest in urban employment has risen, particularly among women and girls, stretching the boundaries of the country’s generally conservative social order.

There is also significant internal displacement due to natural disasters and environmental degradation including river erosion and flooding. River erosion destroys people’s habitats and livelihoods, while floods jeopardize homesteads and financial resources. These impacts can increase poverty and drive people towards urban centers and may also contribute to economic drivers compelling emigration.

Socioeconomic Context of Migration

The river systems that flow through Bangladesh, which sits in the Ganges Delta, are an essential source of its diverse livelihoods such as traditional monsoon rice farming and fishing. Yet a combination of changing climate conditions and the intensification of human activities is expected to lead to more climate-induced migration internally and, potentially, internationally. More than one-quarter of the population was under 15 years old as of 2022, according to the World Bank, putting pressure on current and future employment opportunities and creating a strong push factor for emigration. Young workers may choose to pursue careers abroad because the local job market is limited.

Since independence, the number of Bangladesh’s educational institutions (both public and private) and graduates have increased significantly at all levels. Most notably, where women once lagged in educational attainment, they have made dramatic gains in the past decade, especially in higher education. However, the country’s educational standards still lag behind international levels.

Poverty has been gradually falling on the back of sustained economic growth over the past two decades. The beginning of the millennium saw almost half of the population living below the international poverty line of $2.15 per day, but national poverty has since shrunk. However, there has been little progress in reducing urban extreme poverty. As urbanization has increased in recent years, so too has extreme poverty in urban areas. Moreover, the country's unemployment rate reached an all-time high of 6.9 percent in November 2021, according to the government, as Bangladesh was buffeted by economic headwinds resulting from the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, although unemployment has since declined.

Impacts of Emigration and Remittances

The vast amount of money sent back by emigrants and others as remittances has been among the most powerful tools in Bangladesh’s economic outlook, contributing to improving the living standards of families and spurring development. Although the country’s domestic garment sector is said to be the highest foreign income earner, accounting for nearly $47 billion in 2023 (more than 10 percent of gross domestic product [GDP]), remittances are likely more important. This is because a significant amount of garment export earnings covers the cost of importing raw materials, thereby reducing net income. Therefore, official remittances, which added up to nearly $21.9 billion in 2023, are likely the top income-generating economic sector for Bangladesh.

International remittance flows have generally risen swiftly since Bangladesh’s independence, increasing from $1 billion in 1993 to $12.8 billion in 2013 and $18.4 billion in 2019 (see Figure 3). During the COVID-19 outbreak, fewer Bangladeshi workers were able to travel overseas and many analysts predicted remittances would decline significantly in Bangladesh and other major remittance-receiving countries. However, recorded remittance transfers to Bangladesh remained resilient, and rose to $21.8 billion in 2020—a 19 percent increase over the previous year.

Figure 3. Remittances to Bangladesh, 1976-2023

Source: BMET, “Foreign Employment and Remittances from 1976 to 2023.”

Remittance inflows through formal channels have remained relatively stagnant since 2020. The World Bank predicts that remittances to South Asian countries in general will slow down somewhat in 2024, although the region is projected to receive the most remittances among those sent to low- and middle-income countries. India, Bangladesh’s neighbor, is the world’s largest remittance recipient (with an estimated $125 billion in remittances via formal channels in 2023) and Pakistan is also a major remittance receiver ($24 billion in 2023). However, it is impossible to calculate precisely how much money comes to Bangladesh and other countries via all forms of remittances, due to the large sums believed to travel through unofficial channels. Because of currency devaluation and exchange rate management policies, among other factors, many people sending money to Bangladesh do so through informal channels such as the hawala system or via gifts and goods that migrants bring with them on their return.

In recent years, Bangladesh’s economy has been steadily growing, with favorable government spending, foreign aid declining as a share of gross national income (GNI), low external debt, and many other positive signs. Not many developing countries have enjoyed such macroeconomic stability for such a long time in recent years. Even when the pandemic arrived, economic stability was not severely affected and the government was able to run a large stimulus package. Remittances have played a significant role in this economic condition.

Social and Other Impacts of Remittances

Remittance-receiving households in Bangladesh tend to be better off financially and socially than others. Families often spend remittances on consumer goods such as food, clothing, education, medical care, and shelter, and this is especially true for poor urban and rural households. This income thereby improves households’ standards of living. Moreover, remittance-receiving households may use a significant portion of the inflows to purchase land and (for agricultural households) improve farming techniques such as by making investments in modern machinery. Because Bangladesh is incredibly vulnerable to natural disasters, remittances place recipient households in a stronger position to bear future risks. This in turn enables private savings, diversified livelihoods, and investment in small businesses.

Remittance-prompted investments in land, agriculture, and housing also boost local markets and stimulate rural economies. These transformations can increase mechanization of agriculture, cash crops, and fisheries, directly contributing to local community development. Remittances can make it easier for receiving households to become self-employed in these sectors and to hire other workers. When households use remittances to construct, expand, or improve their homes, they increase the demand for labor and raw materials, thereby contributing significantly to local employment. Remittance senders also tend to contribute to the public life of their communities of origin by making donations to local schools, colleges, libraries, religious institutions, and other facilities.

Bangladeshi migrants’ opportunities for permanent residence abroad tend to be quite limited. It is mainly for this reason that they remit large amounts, except for what is necessary for their daily expenses. Even migrants who live in destination countries long term often maintain some level of involvement in their community of origin, such as through hometown associations. Emigration and remittances therefore also increase the social standing of receivers, such as by creating opportunities for women to make decisions in the absence of male household heads. Over the long term, this can empower women in patriarchal social systems. And because emigrants tend not to work in fields requiring specialized skills, emigration rarely has the negative impact that brain drain could engender.

Negative Impacts of Migration and Remittances

For the time being, emigration of Bangladeshi laborers does not have significant negative consequences for the country. However, there can be risks to individuals (and their families) who bear the predeparture costs of migration—which are often excessive—meaning migrants must spend time abroad to recoup their money, and workers who cannot complete their contracts may lose sizable sums.

Over the long term, Bangladesh’s dependence on remittances may pose future risks, increasing the need to diversify the country’s fiscal situation. Otherwise, the economy may become vulnerable to headwinds outside of its control. While remittances sent via formal channels did not drop as expected during the pandemic, transfers could still be affected by future events. A potential decline in remittances requires innovative policies that reduce the country's dependence and increase domestic sources of revenue. Since most remittances come from unskilled and semi-skilled laborers, a skilled workforce and new labor markets could lead to employment for different occupations and more resilience to remittance-related challenges.

Bangladesh’s migration governance is multidimensional. The country has made significant progress in priorities such as ensuring the well-being of migrants, protecting their rights, and responding to crises, although there remain some critical problems. For instance, the national framework has focused on labor migration at the expense of other forms of cross-border human mobility, such as humanitarian migration, which may have complicated the government’s efforts to respond to the population of Rohingya refugees. Bangladesh has no law specifically governing refugee and asylum issues, and the government has maintained that the Rohingya population is only temporary.

Abroad, Bangladeshi labor migrants are often exposed to risks such as low and unpaid wages, workplace abuses, and scams, which can reduce the benefits of emigration. To mitigate these risks, Bangladeshi diplomatic missions have sought to ensure access to channels where migrants can seek protection and assistance. The government has set an ambitious target of earning a cumulative $150 billion through remittances as part of its Eighth Five-Year Plan (running from mid-2020 to mid-2025). To reach this target, the Ministry of Expatriates' Welfare and Overseas Employment has been tasked with creating an overseas employment market expansion roadmap. The target was part of a ten-point agenda that includes initiatives for institutional and legal reforms, skills development, access to finance, and protection of rights and well-being. Bangladesh has formal and informal remittance service providers and a regulatory framework for managing remittances at home and abroad by state and non-state institutions. Among these are commercial banks, money transfer operators, and foreign exchanges.

Several ministries are primarily responsible for managing Bangladesh's labor migration, return, and integration processes: the Ministries of Home Affairs, Foreign Affairs, Finance, Civil Aviation and Tourism, and Expatriate Welfare and Overseas Employment. These ministries work through various embassies, high commissions, and directorates, and are generally seen to be effective in protecting the rights of expatriate Bangladeshis.

A Forecast of Continual Growth

Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world and its population growth shows little sign of slowing down, so it will likely remain a country of origin for labor migrants for many years to come—not least because the country’s enviable economic growth over recent decades has been conditioned in part on migration. Currently driven by unskilled and semi-skilled expatriate labor, the dynamics of migration and remittances could be strengthened through policies that push labor migrants into higher-skilled sectors, making them less vulnerable to changing economic conditions abroad. Increasing population density, haphazard planning, and the impacts of climate change are likely to increase the vulnerability of many households across Bangladesh, particularly as the risks of tidal flooding and salinization are expected to increase.

The country’s economy has expanded at a significant pace in recent years, helping it achieve lower-middle income status in 2015 and put it on a path to graduate off the United Nations’ list of least developed countries in 2026. Remittances are one of the strongest foundations of this economic development. As such, policymakers would be wise to take steps to reduce migration vulnerabilities, especially excessive costs and risky journeys. Particularly as a rising number of Bangladeshi women leave to work abroad, gender-sensitive policy, legal, and protection frameworks could help ensure migrants achieve the greatest benefit from their employment and travel through safe, orderly, regular, and responsible processes. Finally, because emigrants still tend to be male household heads and other men, policymakers should be conscious of potential problems and opportunities that may arise as families experience social change when women who stay behind gain new social status due to their investing and managing of remittances. Far-reaching plans would help ensure that current emigrants do not suffer financial risks and insecurities when they return to the country, and let future migrants follow safely in their footsteps.

Sources

Bangladesh Bureau of Manpower, Employment, and Training (BMET). 2024. Foreign Employment and Remittances from 1976 to 2023. Updated January 27, 2024. Available online.

Central Bank of Bangladesh. 2024. Yearly Data of Wage Earner's Remittance. Updated March 2024. Available online.

Chowdhury, Mamta B. and Fazle Rabbi. 2014. Workers’ Remittances and Dutch Disease in Bangladesh. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 23 (4): 455-75.

Government of Bangladesh and UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Joint Government of Bangladesh – UNHCR Population Factsheet (as of 31 March 2024). Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh and UNHCR. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021. Migration in Bangladesh: A Country Profile 2018. Geneva: IOM. Available online.

Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD)/World Bank Group. 2023. Remittance Inflows. Updated December 2023. Available online.

Mannan, Kazi Abdul and Khandaker Mursheda Farhana. 2023. Motivational Factors of Migration from Bangladesh to Italy. In Routledge Handbook of South Asian Migrations, ed. Ajaya K. Sahoo. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

Moniruzzaman, Md. and Md. Masud Parves Rana. 2016. History, Factors, and Trends of Migration in Bangladesh. Journal of Life and Earth Science 11: 31-6. Available online.

Pattisson, Pete et al. 2021. Revealed: 6,500 Migrant Workers Have Died in Qatar since World Cup Awarded. The Guardian, February 23, 2021. Available online.

Ratha, Dilip, Vandana Chandra, Eung Ju Kim, Sonia Plaza, and William Shaw. 2023. Migration and Development Brief 39: Leveraging Diaspora Finances for Private Capital Mobilization. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Operational Data Portal: Myanmar Situation. Updated January 31, 2024. Available online.

UN Population Division. 2020. International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin. Available online.

---. 2022. World Population Prospects 2022: File GEN/01/REV1: Demographic Indicators by Region, Subregion, and Country, annually for 1950-2100. Updated July 2022. Available online.