You are here

Ecuador Juggles Rising Emigration and Challenges Accommodating Venezuelan Arrivals

A man with potatoes in Ecuador. (Photo: ©FAO/Claudio Guzman)

Haga clic aquí para leer este artículo en español.

In the past ten years, Ecuador has emerged as a significant destination for South American migrants, a country of transit for those heading north, and a renewed source of emigration, mostly to the United States. Located adjacent to Colombia, near Venezuela, and on a popular migration route through the Americas, the small Andean country of approximately 17 million people has found itself enmeshed in the region’s evolving mobility trends and has responded to the changing circumstances with a mix of policies that have produced some unforeseen outcomes.

Dive In:

-

There have been three eras of Ecuadorian emigration, starting in the 1970s

-

Three-fourths of emigrant Ecuadorians live in the United States or Spain

-

Ecuador hosts the fourth-largest Venezuelan migrant population worldwide

-

Political turmoil and security concerns are likely to persist, compelling additional emigration

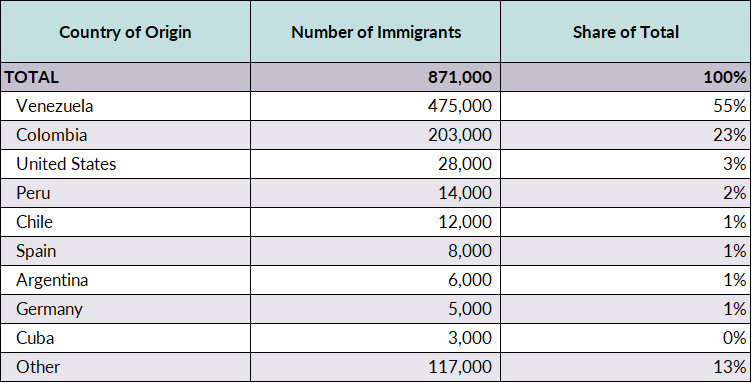

Approximately 871,000 immigrants lived in Ecuador as of the 2020-23 period, accounting for about 1 out of every 20 residents (see Table 1). Most were Venezuelans who fled their country’s economic and political crisis, and slightly more than one-quarter were Colombians, many of whom arrived during Colombia’s long-running civil war. The Venezuelan population is relatively new, mostly arriving since the late 2010s, and includes many who intended to stop only temporarily on their way to Brazil, Chile, Peru, or the United States, but who have remained. There are also a small number of lifestyle migrants, mostly from the United States, who have sought out Ecuador’s relatively high standard of living, affordability, and historical security. Other nationalities, such as Haitians and smaller numbers of Afghans, Cubans, and nationals from a variety of African countries, have also transited through Ecuador.

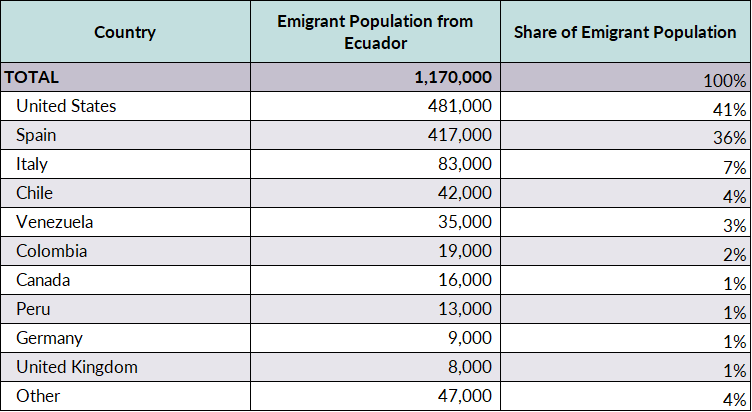

Since the early 1980s, Ecuador has experienced three major waves of emigration, and as of mid-2020 about 8 percent of its population (1.2 million Ecuadorians) lived abroad, according to UN data. These emigrants accounted for the third-largest Latin American nationality in both Italy and Spain, and one of the largest immigrant groups in metro New York. The first wave was primarily from southern Ecuador, comprised of tens of thousands of people who departed in the early 1980s and headed mainly to the United States. The second wave, commonly attributed to a banking and political crisis in the late 1990s and early 2000s, sent more than 500,000 Ecuadorians to Spain, the United States, and Italy. The current emigration period involving hundreds of thousands of Ecuadorians began in 2019 and continued as of this writing, set off by factors including an increase in violence and domestic insecurity and the lasting economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most current emigration is irregular and originates throughout the country. In a change from the past, a significant percentage is of families and a smaller number of unaccompanied children.

Table 1. Immigrants in Ecuador, by Country of Origin, 2020*

* The table relies on the most recent authoritative data available. Data are for mid-2020 except for the Venezuelan totals, which are for August 2023.

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin,” accessed September 15, 2023, available online; Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V), "Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela: August 2023," September 5, 2023, available online.

This country profile offers an overview of the historical and recent migration patterns to, from, and through Ecuador, examining policies in the country and internationally that affect migration. It also offers details about conditions in major destination countries for Ecuadorians, the role of remittances, and prospects for the future.

Table 2. Top Destinations for Ecuadorian Emigrants, 2020*

* Data are for 2020 except for the United States, which reflect 2021 totals.

Sources: UN DESA Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin;” U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimate, accessed September 15, 2023, available online; Spain's Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE), “Población (españoles/extranjeros) por País de Nacimiento, sexo y año,” accessed September 15, 2023, available online.

Historical Immigration Patterns

Ecuador is an ethnically diverse country, due in part to its varied migration patterns among Africans, Europeans, Middle Easterners, and Indigenous people since the pre-colonial era. Although the lack of mining and significant export crops (except for cocoa) prevented Ecuador from being a locus of European settlement during the colonial era, it was nonetheless home to sizable population movements.

Pre-Colonial and Colonial Era

The population of what is now Ecuador witnessed considerable disruption before and during Europeans’ arrival. The Inca invaded from modern-day Peru during the latter half of the 15th century and Spanish conquerors arrived in 1534. As a result of introduced diseases, abuse, and the enslavement that followed, more than 70 percent of the Indigenous population had died by the end of the 16th century.

After the initial Spanish arrivals and imposition of authority under the Spanish crown, few Spaniards or other Europeans immigrated to Ecuador during the colonial era, which lasted until military victory secured the country’s independence in 1822. The arrival of a few English migrants, some Spanish traders, and a handful of other Europeans was the exception.

There was a small but significant population of enslaved people from Africa. During the 16th and 17th centuries, colonial authorities in Quito, the capital, arranged for the shipment of enslaved Africans, who were put to work in the cities of Ibarra, Guayaquil, and the gold mines of modern-day Colombia’s Popayán. A smaller number of enslaved Africans were taken to Quito, Cuenca, and other urban areas. Up to 12,000 enslaved Africans lived in the colonial district of Quito, which extended into what is now southern Colombia. There was also a notable number of enslaved people and their descendants in what is now Esmeraldas Province, along the Colombian border. This population formed in the mid-16th century, when at least two Peru-bound ships carrying enslaved Africans from Panama wrecked on the shores; Africans established a maroon society and maintained autonomy during much of the colonial era.

Post-Independence

With the exception of Spaniards who became traders, Ecuador received few of the Europeans who migrated elsewhere in Latin America during the 19th and early 20th centuries. An 1890 census of Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city, recorded fewer than 5,000 immigrants, more than half of whom were from neighboring Peru.

Ecuador’s cocoa export boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the arrival of Arab-speaking, predominantly Christian immigrants with ancestry traced to modern-day Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria. Now generally categorized as “Lebanese,” these individuals tended to become merchants and traders in Guayaquil. It is unknown how many migrated to Ecuador starting in the 1870s, but the economic and political influence of their descendants has surpassed their numbers. Some of the most successful business families in Ecuador are of “Lebanese” descent. Two presidents in the 1990s were of Arab descent (Abdalá Bucaram and Jamil Mahuad), as is Otto Sonnenholzner, vice president from 2018 to 2020 and a 2023 presidential candidate.

In 1940, approximately 6,000 Germans lived in Ecuador, half of whom were Jewish refugees. About 463 of them were deported at the behest of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), as part of a U.S. strategy to contain what it perceived to be Germany’s war efforts in Latin America.

Emigration: Economic Crises and Three Eras of Departures

Ecuadorian emigration prior to the 1960s was minimal. A small number of people migrated to Venezuela and, by the 1940s, to the United States. Between 1930 and 1959, approximately 11,000 Ecuadorians became U.S. lawful permanent residents, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). By the 1960s, small communities of Ecuadorians could be found in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York.

First Period of Emigration

The southern provinces of Azuay and Cañar around Cuenca, Ecuador’s third-largest city, formed the core migrant-sending zone in Ecuador in the 1970s and 1980s. The main sending communities practiced subsistence agriculture and had a tradition of women weaving Panama hats for export to New York, as well as male seasonal migration to the Ecuadorian coast. When the Panama hat trade declined in the 1950s and 1960s, pioneering migrants, mainly young men, used industry connections to migrate to New York, mostly without authorization. Many worked in restaurants as busboys or dishwashers, and a smaller number worked in factories or construction.

Migration remained slow but persistent during the 1970s and grew rapidly during the “lost decade” of the 1980s, when a debt crisis, hyperinflation, and subsequent austerity programs were particularly onerous on working-class Ecuadorians. Among those most affected were small farmers, thousands of whom opted to emigrate.

Most migrants paid intermediaries—coyotes or document forgers—for clandestine passage to the United States, overwhelmingly to metro New York, but also to Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, and Minneapolis. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 allowed more than 16,000 Ecuadorians to gain legal permanency residence (also known as getting a green card), which let them sponsor the legal immigration of family members. The Ecuadorian population in the United States increased from about 37,000 in 1970 to more than 143,000 in 1990.

Second Emigration Period

Ecuador’s second emigration wave began in the late 1990s, when the country experienced economic and political crisis anew. Low oil prices (a problem for the crude-exporting country), political instability, and financial mismanagement led unemployment to rise and the poverty rate to reach 64 percent of the population by the end of 1999. In 2000, Ecuador adopted the U.S. dollar as its national currency. Millions of people lost money in the banking crisis that enveloped the country.

Between 500,000 and 1 million Ecuadorians went overseas between 1998 and 2006. The United States and Italy were major destinations, as was Spain, where few Ecuadorians had lived previously and where they could enter visa-free as tourists (the law changed in 2003). This migration was much more geographically and socioeconomically diverse than the previous period of emigration. Emigrants came from every province and were more urban and better educated than in the past; they also came from various ethnicities, including several Indigenous groups.

Spain offered plentiful low-skilled work. Most Ecuadorian women worked in domestic services such as cleaning and child and elderly care, while men found employment in the construction, agriculture, and service industries. By 2005, as many as 487,000 Ecuadorians resided in Spain, and for a few years they comprised the largest immigrant group there.

Emigration from southern Ecuador mostly targeted the United States. Thousands of Ecuadorians traveled to Mexico or Guatemala on their way north, often via fishing trawlers or other boats. Between fiscal year (FY) 1999 and FY 2006, more than 8,000 Ecuadorians were detained by the U.S. Coast Guard, likely representing a small percentage of all migrants taking to the seas. Travel via this dangerous maritime route ended soon thereafter; the Coast Guard detained fewer than 20 Ecuadorians in the period between 2007 and 2015.

After the peak of this emigration era subsided, a considerable number of Ecuadorians followed to join family members in the United States and Spain. From 2010 to 2021, an estimated 121,000 Ecuadorians received a U.S. green card (an average of more than 10,000 annually), more than 80 percent through family-based pathways. Similarly, in 2005 Spain implemented a sweeping regularization law (Real Decreto 2393/2004) that granted legal status to nearly 200,000 Ecuadorians, many of whom received Spanish nationality, which allowed them to bring family members to Spain.

Third Period of Emigration

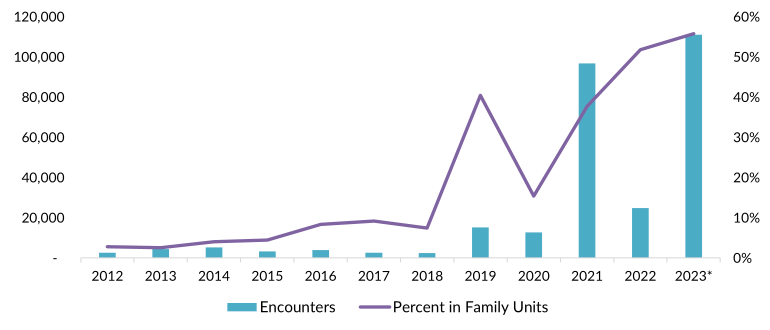

Irregular migration to the United States continued through the 2000s and 2010s, but in considerably smaller numbers than during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Between FY 2012 and FY 2018, for example, an average of nearly 3,600 Ecuadorians were apprehended annually by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). In 2019, however, an uptick in irregular migration began. The number of CBP encounters of Ecuadorians jumped to more than 15,000 in FY 2019, before dipping during the pandemic in FY 2020 and rebounding dramatically to nearly 97,000 in FY 2021. After dropping in FY 2022, more than 104,000 Ecuadorian encounters were on pace to be recorded in FY 2023 (see Figure 1). These data are of episodes, not individuals, and a fair number are repeat crossers. Still, the trend points to a clear increase since FY 2019.

Figure 1. U.S. Customs and Border Protection Encounters of Ecuadorian Migrants and Share Encountered as Families, FY 2012-23*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 are projected based on data through August, the most recent month available at this writing.

Note: The term encounters is used by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to encompass apprehensions as well as the expulsions that occurred under the pandemic-era Title 42 policy, which began in March 2020 and was lifted in May 2023.

Sources: Data for FY 2012 through FY 2021 are from Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Border Patrol Arrests,” accessed September 15, 2023, available online; data for FY 2022 and FY 2023 are from CBP, “Nationwide Encounters,” updated September 22, 2023, available online.

Importantly, about half of these encounters are of “family units,” the CBP term for parents or other guardians arriving with minor children. Ecuadorian families accounted for less than 10 percent of all encounters prior to FY 2019, but their share has risen significantly since then.

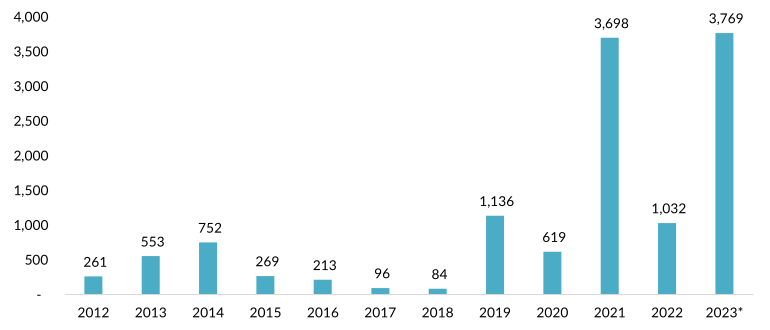

There has also been a similar increase in encounters of unaccompanied Ecuadorian children. Although unaccompanied minors accounted for less than 5 percent of encounters of Ecuadorians in recent years—much lower than rates of unaccompanied minors from Mexico and northern Central America—the numbers nonetheless increased dramatically compared to previous years.

Figure 2. Encounters of Unaccompanied Migrant Children from Ecuador at the U.S.-Mexico Border, FY 2012-23*

* Data for FY 2023 are projections based on data through the first 11 months of the fiscal year.

Sources: Data for FY 2012 through FY 2021 are from TRAC, “Border Patrol Arrests;” data for FY 2022 and FY 2023 are from CBP, “Nationwide Encounters.”

Irregular migration to the United States was facilitated by a Mexican policy that allowed Ecuadorians to travel to Mexico without a visa. Since August 2021, however, Mexico has required a visa from Ecuadorians, and this route has become less accessible. Instead, migrants have hired smugglers to lead them to northern Mexico, where they attempt to cross the border or turn themselves into U.S. authorities. Some do so by first flying to Nicaragua or Panama on a tourist visa and then proceeding through Central America. Others migrate in small groups without a coyote and use smartphones as guides, crossing into Colombia and through the Darien Gap to Panama. The number of Ecuadorians crossing the treacherous Darien Gap jungle skyrocketed after Mexico imposed the visa requirement, from fewer than 400 in 2021 to more than 29,000 in 2022 and in excess of 48,000 in just the first nine months of 2023. In both 2022 and 2023, Ecuadorians comprised the second-largest group of Darien crossers, after Venezuelans.

Several factors have contributed to the current emigration. Consequences of the pandemic undoubtedly played a large part; the economy was already struggling when the disease infected more than 1 million Ecuadorians and killed at least 36,000. Unemployment increased and the poverty rate, which had been declining for most of the decade, shot up to 33 percent in 2020. Although the country’s economy has recovered as global oil prices have risen, this has not translated into better living conditions for millions of low-wage workers.

Another factor has been the frustration and despair stemming from persistent corruption, increasing crime and political violence, the growing power of narcotraffickers, and the government’s inability to address these issues. Ecuador had previously been largely spared the trafficking-related violence that afflicted Colombia for decades, but has recently become a battleground for criminal organizations seeking to transport cocaine to the United States and Europe. Ecuadorian gangs (Los Choneros and Lobos) apparently have worked with Mexican criminal groups such as the Sinaloa and Jalisco Nueva Generación cartels to export tons of cocaine from Ecuador’s ports, including Esmeraldas, Manta, and especially Guayaquil. Albanian groups have also been involved, helping export cocaine to Europe. The growing role of organized crime was made clear with the assassination of Manta’s mayor in July 2023, and the killing of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio in Quito a few weeks later. Villavicencio had been an anti-corruption crusader and had a good chance to advance in the election.

There has been a widespread sense that police cannot stop the increase in crime and extortion. The homicide rate more than quadrupled from 5.8 per 100,000 people in 2017 to 25.9 in 2022. Although gang violence has tended to be centered in Guayaquil, it has nonetheless shaken the whole country. Feelings of personal insecurity have given rise to neighborhood watch groups and vigilante justice, even in places such as Cuenca, which had been spared much of the violence.

Finally, family reunification has been a major migration driver, especially for Ecuadorians with family members in the United States. Many Ecuadorians believe that migrants with children will be allowed into the United States, a belief that followed the repeal of President Donald Trump’s “zero-tolerance” policy that resulted in thousands of children being separated from their parents. In FY 2022, nearly 18,000 Ecuadorians applied for asylum in the United States, a five-fold increase from the year before.

Ecuadorians Abroad: Trends in Main Destination Countries

Of the 1.2 million Ecuadorians living abroad as of 2020, more than three-quarters were in the United States or Spain. Most of the rest of the population is dispersed across South America and Europe.

Ecuadorians in the United States

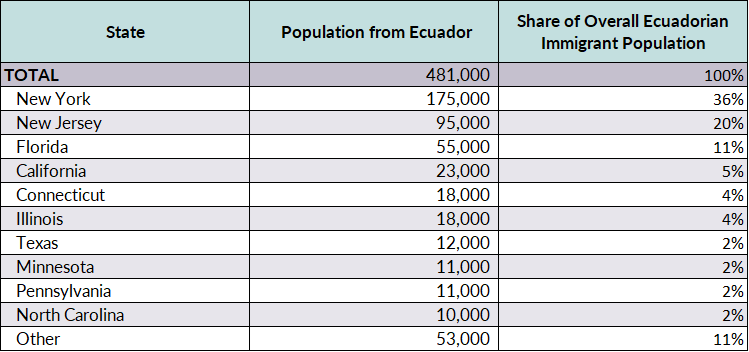

The number of Ecuadorians in the United States has increased steadily from an estimated 429,000 in 2013 to more than 481,000 in 2021. Ecuadorians remain heavily concentrated in the New York metro area, where about 55 percent live and where they comprise the third-largest Latin American immigrant group, behind Dominicans and Mexicans. An estimated 77,000 Ecuadorians lived in the borough of Queens, long considered the first destination for many Ecuadorian immigrants, as of the 2017-21 period. Another 11 percent lived in Florida (primarily metro Miami), and about 5 percent in California (primarily metro Los Angeles). The Ecuadorian diaspora in the United States, estimated at 947,000 in 2021 by Migration Policy Institute (MPI) calculations, is divided evenly between those born in Ecuador and those who identify as having Ecuadorian ancestry or heritage.

Table 3. Ecuadorian Immigrant Population in the United States, by State, 2021

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimate.

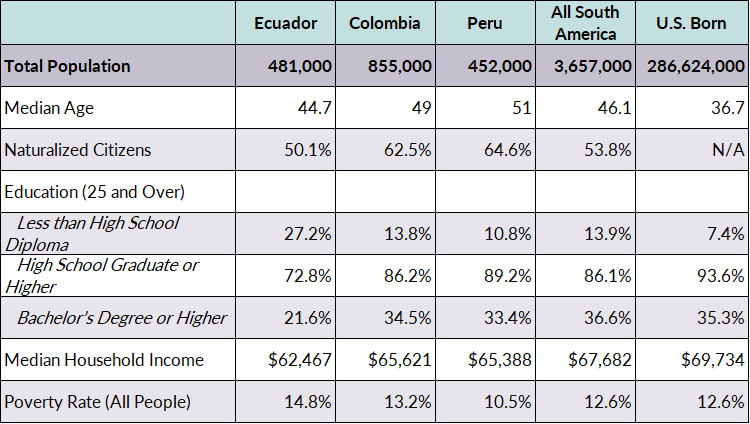

While there is little social research on Ecuadorians in the United States, the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) provides some important indicators (see Table 4). Their educational attainment and median household income tends to be lower than that of the native-born population and all South Americans, while their poverty rate is higher.

Table 4. Socioeconomic Indicators of the U.S. Population, by Origin, 2021

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimate.

An estimated 162,000 Ecuadorians in the United States lacked legal status as of 2021, according to estimates from MPI, making them the 11th largest unauthorized population. From FY 2017 to FY 2021, an average of more than 2,000 Ecuadorians were removed from the United States per year, about half of whom had a criminal conviction.

Ecuadorians in Spain

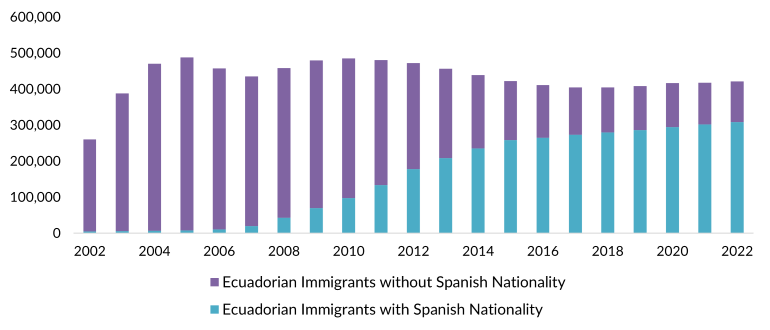

The number of Ecuadorians in Spain has declined slightly since its peak in the early 2000s, although nearly 243,000 Ecuadorians acquired Spanish nationality between 2005 and 2013 (see Figure 3). This total, however, masks notable population movements. Nearly 156,000 Ecuadorians migrated legally to Spain between 2008 and 2021, and, because of the nature of the European Union’s free-movement regime, an unknown number subsequently went elsewhere in the bloc. Ecuadorian immigrants remain concentrated in metro Madrid (31 percent as of 2022) and Barcelona (21 percent), as well as the agricultural provinces of Murcia and Valencia (21 percent combined). The most recent National Immigrant Survey, from 2007, showed that men worked primarily in construction, agriculture, and industry, while women were concentrated in domestic service, hotel work, and commerce.

Figure 3. Ecuadorian Immigrants in Spain, by Nationality, 2002-22

Source: INE, “Población (españoles/extranjeros) por País de Nacimiento, sexo y año.”

During the Great Recession of 2008-09, economic pressures and Spanish policies incentivized immigrants to return to their origin countries. Spain’s “pay-to-go” programs coincided with efforts by Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa (in office from 2007 to 2017) to reach out to Ecuadorians abroad through a program called Welcome Home: For a Voluntary, Dignified and Sustainable Return (Plan Bienvenid@ A Casa: Por un regreso voluntario, digno y sostenible). The program encouraged return migration for families by helping with their transition, including making them eligible for start-up funds for certain investments. Yet between 2009 and 2013, fewer than 6,500 Ecuadorians took advantage of these incentives to return, far fewer than anticipated.

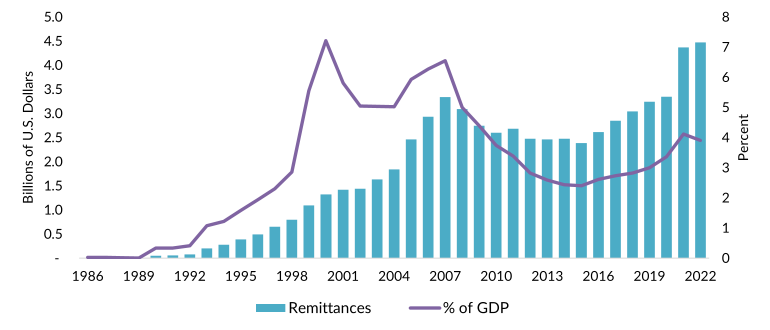

Ecuadorians overseas generate billions of dollars of remittances annually, which help numerous households and boost the Ecuadorian economy. Remittances sent via formal channels increased quickly in the early 2000s with the second wave of emigration, reaching U.S. $3.3 billion in 2007 (see Figure 4). They declined somewhat until 2015, when they began a steady increase and topped $4.4 billion in 2022. This growth was likely due to increasing financial help from migrants and others concerned about people in Ecuador during the pandemic, but also as new emigrants remitted money to cancel debts acquired for migration. The importance of remittances, measured as percent of gross domestic product (GDP), has fluctuated based on the strength of the Ecuadorian economy. As oil revenues and Ecuador’s GDP increased during the 2010s, the relative contribution of remittances to the overall economy declined to a low of 2.4 percent in 2014 and 2015, but rebounded to about 4 percent in 2022.

Figure 4. Remittances to Ecuador, Total Volume and as a Share of GDP, 1986-2022

Source: World Bank, “Personal Remittances,” updated September 15, 2023, available online.

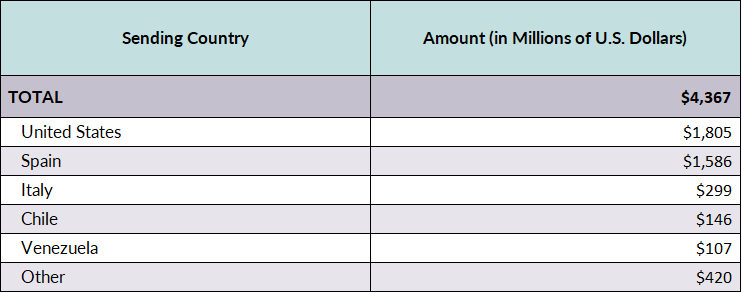

The vast majority of remittances originate from the countries hosting the largest emigrant populations: the United States, Spain, and Italy.

Table 5. Remittances Received in Ecuador, by Sending Country, 2021

Source: Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD)/World Bank Group, “Bilateral Remittance Matrix,” updated December 2022, available online.

Ecuador as a Country of Transit and Destination

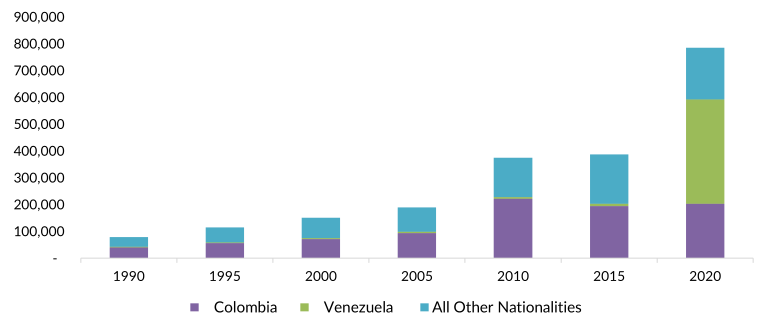

The immigrant population in Ecuador has grown substantially in the past 25 years, most remarkably since 2015 (see Figure 5). In 2000, the 227,000 immigrants living in Ecuador made up less than 2 percent of the total population of about 12.6 million; most had fled conflict in Colombia, but there were also a small number of Peruvians and lifestyle migrants from North America. As of 2023, an estimated 871,000 immigrants comprised approximately 5 percent of the overall population, an increase explained mostly by the arrival of migrants from Venezuela since 2015, when that country’s political and economic crisis worsened. The 475,000 Venezuelans in Ecuador as of August 2023 comprised about 6 percent of the population of 7.7 million emigrant Venezuelans, and the fourth-largest Venezuelan emigrant population worldwide, after those in Colombia, Peru, and Brazil.

Figure 5. Immigrant Population in Ecuador by Origin, 1990-2020

Source: UN DESA Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin.”

In addition to those who settled in Ecuador, it is likely that another 1.2 million Venezuelans have passed through the country since 2017, heading to places such as Peru, Brazil, and Chile. Use of Ecuador as a transit country is not new. From 2008 until 2010, the Correa administration eliminated visa requirements for all nationalities, before changing course and requiring visas for some arrivals, which encouraged travelers from around the world to use Ecuador as a pit stop on their way to the United States, Canada, or elsewhere.

Many Venezuelans arrived in the wake of Ecuador’s 2017 Human Mobility Law (Ley Orgánica de Movilidad Humana), which granted substantial protection for humanitarian migrants and victims of human smuggling and trafficking. The law allows immigrants to legally work and access the social security system, provides a pathway for legal status and integration opportunities, and commits Ecuador to the international principle of nonrefoulement (which forbids returning a person to a place where they would be in danger). This law was consistent with other treaties Ecuador had signed and with its 2008 constitution, which recognizes migration and human mobility as rights and requires the government to safeguard migrants’ rights.

The progressive legislation and reception for Venezuelans was challenged starting in 2018 by the administration of President Lenín Moreno (in office from 2017 to 2021), when the scope of inflows became a humanitarian crisis. Moreno declared a state of emergency in three provinces in 2018 as nearly 30,000 Venezuelans crossed into Ecuador in just one week in August. The administration required Venezuelans have a valid passport to enter, and in 2019 implemented visa requirements that left thousands stuck in Colombia and elsewhere. Others were forced to cross into Ecuador irregularly, and many were unable to work legally. These restrictive policies coincided with a rise in public animosity towards Venezuelans and Colombians.

At the same time, the country sought to accommodate some of the new arrivals. In 2019, Ecuador began a regularization program known as VERHU (Visa De Excepción Por Razones Humanitarias, or Exception Visa for Humanitarian Reasons), which offered two years of legal status to migrants in irregular status, but stringent and expensive requirements meant only about 50,000 could benefit. In 2022, the administration of President Guillermo Lasso began a much more comprehensive regularization program that applied to virtually all irregular immigrants. As of August 2023, approximately 202,000 immigrants had enrolled in the program and 62,000 had received a residency visa, known as VIRTE (Visa de Residencia Temporal de Excepción, or Exception Temporary Residence Visa).

Ecuador faces several major migration-related challenges. The ongoing third era of emigration is likely to continue and may diversify to new destinations with the increase in narcotrafficking violence, crime, a sluggish economy, and despair about the future. Since most emigration will likely be irregular, many Ecuadorians are sure to acquire debt to pay for coyotes and risk their well-being traveling dangerous routes through the Darien Gap and northern Mexico. Ecuadorian leaders may decide to work with the United States and other governments to restrict emigration, but as long as there are powerful incentives to migrate there is a limit to how effective these policies can be. Policies such Mexico’s requirement that Ecuadorians obtain a visa will likely push people to travel irregularly, through more treacherous and expensive routes. Efforts to stem the flow will likely only be successful when individuals see a safer, more prosperous future in their own country.

Another major challenge is Ecuador’s continued role as a transit and destination country for some migrants. Ecuador has wavered on its commitment to protect forcibly displaced people from Colombians and Venezuela, pushing them into difficult circumstances. Yet the ongoing regularization program is a hopeful sign that Ecuador may change course.

Finally, the political turmoil in Ecuador, punctuated by the assassination of a presidential candidate, is likely to persist. Daniel Noboa will take office in late 2023 with numerous economic and security issues on the agenda. Managing Ecuador’s ongoing era of emigration, working to protect Ecuadorians abroad, and regulating its status as a destination and transit country for migrants will be part of the challenges ahead.

Sources

Ayala Mora, Enrique. 2005. Resumen de Historia Del Ecuador. Quito: Corporación Editora Nacional.

Becker, Marc. 2018. The FBI's Role in Expelling Germans from Ecuador during the 1940s. Bulletin of Latin American Research 37 (3): 306-20.

Bernardi, Fabrizio, Luis Garrido, and Maria Miyar. 2010. The Recent Fast Upsurge of Immigrants in Spain and Their Employment Patterns and Occupational Attainment. International Migration 49 (1): 148-87.

Beyers, Christiaan and Esteban Nicholls. 2020. Government through Inaction: The Venezuelan Migratory Crisis in Ecuador. Journal of Latin American Studies 52 (3): 633-57.

Boccagni, Paolo and Francesca Lagomarsino. 2011. Migration and the Global Crisis: New Prospects for Return? The Case of Ecuadorians in Europe. Bulletin of Latin American Research 30 (3): 282-97.

Brey, Elisa and Mikolaj Stanek. 2013. Analysis of Existing Quantitative Data on Family Migration: Spain. Oxford, UK: The Impact of Restrictions and Entitlements on the Integration of Family Migrants (IMPACIM). Available online.

Bryant, Sherwin. 2006. Finding Gold, Forming Slavery: The Creation of a Classic Slave Society, Popayán, 1600-1700. The Americas 63 (1): 81-112.

Carrasco Carpio, Concepción and Carlos García Serrano. 2011. Inmigración y mercado de trabjo. Informe 2011. Madrid: Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social. Available online.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics. 2022. 2021 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. Available online.

Ecuador Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo. N.d. Población y Demografía. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

Freeman, Will. 2023. A Surge in Crime and Violence Has Ecuador Reeling. World Politics Review, June 9, 2023. Available online.

Freier, Luisa Feline and Kyle Holloway. 2019. The Impact of Tourist Visas on Intercontinental South-South Migration: Ecuador’s Policy of “Open Doors” as a Quasi-Experiment. International Migration Review 53 (4): 1171-208. Available online.

Furst-Nichols, Rebecca and Karen Jacobsen. 2012. Refugee Livelihoods in Urban Areas: Identifying Program Opportunities: Case Study Ecuador. Sommerville, MA: Tufts University Feinstein International Center. Available online.

Glatsky, Genevieve and José María León Cabrera. 2023. How Nacro Traffickers Unleashed Violence and Chaos in Ecuador. The New York Times, August 17, 2023. Available online.

Guglielmelli White, Ana. 2011. In the Shoes of Refugees: Providing Protection and Solutions for Displaced Colombians in Ecuador. Research paper 217, UNHCR Policy Development and Evaluation Service, Washington, DC, August 2011. Available online.

Hayes, Matthew. 2018. Gringolandia: Lifestyle Migration under Late Capitalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Herrera, Gioconda. 2019. From Immigration to Transit Migration: Race and Gender Entanglements in New Migration to Ecuador. In New Migration Patterns in the Americas: Challenges for the 21st Century, eds. Andreas E. Feldmann, Xóchitl Bada, and Stephanie Schütze. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Herrera, Gioconda Mosquera, María Isabel Moncayo, and Alexandra Escobar García. 2012. Perfil Migratorio del Ecuador 2011. Quito: International Organization for Migration (IOM). Available online.

Hiemstra, Nancy. 2019. Detain and Deport: The Chaotic US Immigration Enforcement Regime. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

---. 2023. The Value of Illegality: Venezuelan Migrants in Ecuador and the (Re) Entrenchment of Neoliberal Capitalism. International Migration Review: 01979183231182679.

Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V). 2023. Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela: August 2023. September 5, 2023. Available online.

Jokisch, Brad. 2007. Ecuador: Diversity in Migration. Migration Information Source, February 1, 2007. Available online.

---. 2014. Ecuador: From Mass Emigration to Return Migration? Migration Information Source, November 24, 2014. Available online.

Jokisch, Brad and David Kyle. 2005. Las transformaciones de la migración transnacional del Ecuador, 1993-2003. In La migración ecuatoriana: transnacionalismo, redes, e identidades, eds. Gioconda Herrera, Maria Cristina Carrillo, and Alicia Torres. Quito: FLACSO-Plan Migración, Comunicación y Desarrollo.

Jokisch, Brad and Jason Pribilsky. 2002. The Panic to Leave: Economic Crisis and the New Emigration from Ecuador. International Migration 40 (4): 75-102. Available online.

Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD)/World Bank Group. 2022. Bilateral Remittance Matrix. Updated December 2022. Available online.

Kyle, David. 2001. Transnational Peasants: Migration, Networks and Ethnicity in Andean Ecuador. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lane, Kris. 2002. Quito 1599: City and Colony in Transition. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Levinson, Amanda. 2005. The Regularisation of Unauthorized Migrants: Literature Survey and Country Case Studies. Oxford, UK: Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford. Available online.

Malo, Gabriela. 2022. Between Liberal Legislation and Preventive Political Practice: Ecuador’s Political Reactions to Venezuelan Forced Migration. International Migration 60 (1): 92-112.

Margheritis, Ana. 2011. Todos Somos Migrantes (We Are All Migrants): The Paradoxes of Innovative State-Led Transnationalism in Ecuador. International Political Sociology 5: 198-217.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI). N.d. Top Diaspora Groups in the United States, 2021. Accessed September 18, 2023. Available online.

Miller, Sarah and Daphne Panayotatos. 2019. A Fragile Welcome: Ecuador’s Response to the Influx of Venezuelan Refugees and Migrants. Washington, DC: Refugees International. Available online.

Morales, Laura and Katia Pilati. 2014. The Political Transnationalism of Ecuadorians in Barcelona, Madrid and Milan: The Role of Individual Resources, Organizational Engagement and the Political Context. Global Networks 14 (1): 80-102.

Newland, Kathleen, Elizabeth Collett, Kate Hooper, and Sarah Flamm. 2016. All at Sea: The Policy Challenges of Rescue, Interception, and Long-Term Response to Maritime Migration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Newson, Linda A. 1995. Life and Death in Early Colonial Ecuador. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Panama National Migration Service (SNM). N.d. Estadísticas. Accessed October 12, 2023. Available online.

Ramírez, Jacques. 2020. From South American Citizenship to Humanitarianism: The Turn in Ecuadorian Immigration Policy and Diplomacy. Estudios fronterizos 21. Available online.

Ramos, Cristina. 2021. Searching for Stability: Onward Migration and Pathways of Precarious Incorporation in and out of Spain. International Migration 59 (6): 77-92.

Roberts, Lois J. 2000. The Lebanese Immigrants in Ecuador. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Sánchez Bautista, Consuelo. 2017. The Promise of a Welfare State: The Ecuadorian Government Strategy on Emigration and Diaspora Policies between 2007–2016. In Emigration and Diaspora Policies in the Age of Mobility, ed Agnieszka Weinar. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Simanski, John F. 2014. Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2013. Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. Available online.

Spain Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE). N.d. Adquisiciones de nacionalidad por nacionalidad en relación al país de nacimiento. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. Flujo de inmigración procedente del extranjero por año, país de nacimiento y nacionalidad (española/extranjera). Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, comunidades, Sexo y Año. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. Población por comunidades y provincias, país de nacimiento, edad (grupos quinquenales) y sexo. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. Población residente por fecha, sexo, grupo de edad y país de nacimiento. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). Border Patrol Arrests. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

UN Population Division. N.d. International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Census Bureau. N.d. 2021 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimate. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2023. Nationwide Encounters. Updated September 22, 2023. Available online.

Van Hook, Jennifer, Julia Gelatt, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto. 2023. A Turning Point for the Unauthorized Immigrant Population in the United States. MPI commentary, Washington, DC, September 2023. Available online.

World Bank. 2023. Personal Remittances. Updated September 15, 2023. Available online.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2023. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Updated September 13, 2023. Available online.