You are here

Reliant on Labor Migration, the Global South Forges a New Social Contract with Its Citizens

A migrant from Nepal in Qatar. (Photo: © ILO)

The realities of South-South migration remain misunderstood. In popular discourse, migrants’ countries of origin are often inaccurately viewed as weak and migrants themselves are seen as devoid of agency, as stories abound of workers’ harassment and abuse, deportations, and xenophobic violence. But rather than being pushed around by the changing whims of the global economy, labor migrants from the Global South are participating in a complicated geopolitical dance involving countries of origin and destination in other parts of the world. In the process, labor migration is part of the emergence of a new version of the social contract between individuals and their countries.

In This Article

International mobility has become part and parcel of the development strategies of many Global South nations that are responsible for building a robust government that provides services to its citizens but have neither the financial means nor institutional capacity to do so. These countries have embraced migration—and particularly to other countries in the Global South, which has become the most popular type of migration worldwide—as, among other things, a way of offering citizens the opportunity to afford services for them and their loved ones that the governments would have been unable to provide. Yet by linking citizens’ access to basic health care, education, and other services to the ability of individuals and their family members to migrate and work abroad—and bring back money and other resources—governments have contoured their populations’ socioeconomic and political behavior, both domestically and internationally.

In other words, countries across the Global South are witnessing the emergence of a novel manner of state-society relations, which the authors have dubbed the “transnational social contract,” as remittances sent by diasporas step in to finance multiple functions that states historically provided. This situation is exemplified by the emergence of migration management institutions, which signify the centrality of migration in government policymaking, as well as the widening gap between migrants’ remittances and government spending on services such as health care and education in the origin countries. The dynamic has distinct repercussions for labor migration and world politics, as it affords countries of origin and destination a gatekeeper role that helps prevent sociopolitical unrest—at home or abroad. This article explains how South-South migration trends are reimagining the complex relationship between states and their citizens.

The Build-Up and Breakdown of the Social Contract in the Global South

In the aftermath of the process of decolonization in the mid-20th century, newly independent states across the Global South were confronted with the daunting task of nation-building. Central to that process was the construction of ambitious agendas expanding social and political rights to a newly defined citizenry. In India, Indonesia, Tanzania, and other countries, leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Sukarno, and Julius Nyerere rose to power with the desire to fight socioeconomic inequality while maintaining the authority of the new government.

This involved state-sponsored welfare schemes to assist the poor, members of minority ethnic groups, and others. Protectionist industrialization, welfare distribution, and expansive state employment policies were distinguishing characteristics of many new countries. For instance, Malaysia introduced popular quota systems to provide access to public-sector employment and education to ethnic Malays and bhumiputeras (“sons of the soil,” a term referring to certain Indigenous people). Egypt made university education free for all citizens, while guaranteeing state employment to any graduate. India offered rations of food, kerosene, and other essentials to the poorest of the poor. For citizens, the bargain implicit in this social contract was clear: embrace the new nation’s politics, and the government will offer an education, employment, or other material benefits.

Over time, these policies would become increasingly ineffective and costly. Yet any attempt at a top-down reform risked shaking the very foundations of post-independence stability. Tunisia’s decision to lift protective tariffs in the early 1980s led to the “bread riots” in which dozens of people were killed. This revolt paved the way for the 1987 fall of President Habib Bourguiba, who had been in power for 30 years and orchestrated the country’s independence. More recently, in 2020, India’s efforts at amending the ration system providing food and other items to the poor at subsidized rates resulted in widespread protests and riots, leading to hundreds of deaths. By the end of 2021, the Indian government abandoned efforts at reform.

Filling the Void: Emigration Management Institutions and Remittance-Welfare Gaps

Just as the social contract began to fray, labor emigration emerged as a source of domestic development. Over time, access to foreign labor markets gave rise to much-coveted remittances sent back by individual migrants and others abroad to their family members and loved ones. These funds, which worldwide now triple the size of all official foreign aid, began to supplement and substitute for domestic welfare programs across much of the Global South. States developed emigration management institutions to encourage and govern these large emigration flows. Government agencies worldwide have emerged to manage diaspora relations, safeguard emigrants in distress, and otherwise maintain the origin country’s connections with its nationals abroad.

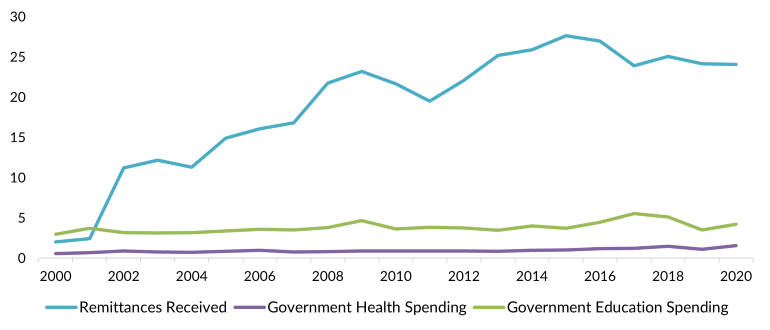

In countries such as Tajikistan, Lebanon, and Nepal, remittances accounted for more than one-quarter of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023, according to the World Bank. In many cases, remittance inflows have outpaced state spending on social projects such as education and health care, a remittance-welfare gap that in many cases is growing ever wider. Nepal, the origin of approximately 2.6 million migrants (many of them in the Middle East), received more than $8 billion in remittances sent through formal channels in 2020. That year, nearly one-quarter of Nepal’s GDP came from remittances, while the government spent just 6 percent of GDP on education and health care (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nepal Government Spending on Education and Health Care, and Remittances Received, as Shares of Gross Domestic Product, 2000-20

Source: World Bank, "World Development Indicators,” updated December 19, 2023, available online.

Together, these elements have combined to form a new transnational social contract, in which origin and destination governments alike simultaneously are able to use the prospect of access to migration (and migration-related remittances) to encourage citizens’ acquiescence to state authority.

How does this operate in action? Countries of origin with weak social welfare systems are able to regulate employment opportunities abroad for their citizens. In Nepal, for instance, the government has played a sizeable role in selecting people to work abroad, distributing recruitment licenses to employers, and has even offered loans to conflict-affected individuals so they would emigrate rather than participate in a Maoist domestic insurgency. Countries of destination, such as those in the Gulf Cooperation Council, enable immigrants’ access to their labor markets but in a precarious state, without granting citizenship or permanent residency. Thus, the transnational social contract grants sending and host states a unique gatekeeper role that mitigates against sociopolitical protest or unrest at home or abroad. Given that emigration is still tightly regulated across many countries of the Global South—including Singapore, Syria, and Taiwan—the prospect of a higher income afforded by an individual’s migration may be foreclosed by demanding more expansive social and political rights in either country of origin or destination. This may present a dilemma pitting one’s hope for a well-paying job against aspirations for greater rights.

Benefits for Countries of Origin and Destination, with Migrants in the Middle

For countries of origin, the transnational social contract serves as a way of immunizing local elites against economic crises, while strengthening citizens’ dependence by regulating their ability to leave and earn money. The infusion of labor migration in evolving state-society relations across the Global South enables government leaders to neglect state welfare services and direct funds elsewhere. As research on remittance sending has demonstrated, this has the potential to strengthen authoritarianism. The transnational social contract has historically enabled autocratic regimes in countries reliant on remittances, such as Egypt, to allocate more state funds towards patronage and domestic security.

Regionally, the transnational social contract enables novel processes of migration diplomacy, as migrants become part and parcel of states’ foreign policy agendas and geopolitical calculations. In particular, it allows countries of origin to leverage their sizable workforce in negotiations with host nations. For instance, in 2022, Saudi Arabia agreed to provide $532 million in back pay to approximately 10,000 Filipino migrants who had been working for Saudi companies that went bankrupt. The agreement followed a dramatic move by the Philippines to temporarily halt deployment of all migrant workers to Saudi Arabia, which relies on approximately 700,000 Filipinos to construct buildings, clean houses, and perform various other jobs. Similar earlier attempts by the Philippines against Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates also proved successful, demonstrating the complex power dynamics of South-South migration.

Still, the balance is weighted towards countries of destination, which can exercise significant veto power over foreign workers’ employment security. In Hong Kong, foreign-born domestic helpers are often subject to abuse, exploitation, and frequent deportations. In fact, across much of the Global South, employment visas and contracts are sometimes unilaterally cancelled or revoked, and there are reasons to be concerned about migrant workers’ rights, as investigations into the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar and other events have demonstrated. This translates to foreign policy, as powerful host states are much more able to engage in coercive migration diplomacy against weaker sending states by depriving them of the opportunity for nationals to seek employment and produce much-needed remittances. For instance, Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in Libya was notorious for deporting migrant workers when bilateral relations with neighboring Arab regimes deteriorated.

Migrants, stuck in the middle, may benefit when origin countries intervene on their behalf, such as in the Philippine cases described above. But they may also be subject to coercion from their countries of origin and destination alike. This is evident in places such as Myanmar, where the government has facilitated migration to other parts of the Global South. With high-interest loans often necessary to cover the cost of emigration, migrants from places such as Myanmar and Nepal can fall prey to debt bondage and other forms of abuse before they even arrive in a country of destination. Governments may also demand a cut of migrants’ paychecks, as was the case for 3,000 North Koreans working in Qatar ahead of the World Cup who were able to keep only about 10 percent of their wages; the remaining funds were sent to North Korean recruitment companies that are part of Kim Jong Un's regime.

Relations between states and individuals are constantly being reshaped, as are relations between states. The emergence over the last half-century of countries relying on South-South migration to spur development is linked to a transnational social contract in which individuals accept a tacit bargain of acknowledging the state’s authority in order to reap the material benefits of migration—at origin and destination. This understanding helps explain why citizens of remittance-dependent countries may be uninterested in viewing their situation as a sign of government failure to provide for their needs.

This analysis is part of a process of viewing “migration from below,” meaning recentering the politics of origin countries. Still, governments may renege on the postcolonial social contract, as many did during the COVID-19 pandemic. Temporary bans on movement worldwide risked sparking political unrest, as many governments proved unable either to secure their citizens’ employment abroad or provide robust domestic services at home. The dramatic increase in movement since the pandemic suggests that the situation may be returning to normal. Yet going forward, individuals may continue to reconsider their relations with the state, with unknown consequences.

Sources

Aben, Ellie. 2022. Philippines Lauds Saudi Move to Compensate Unpaid Filipino Migrant Workers. Arab News, November 19, 2022. Available online.

Adhikari, Jagannath. 2016. Labour Emigration and Emigration Policies in Nepal: A Political-Economic Analysis. In South Asia Migration Report 2017: Recruitment, Remittances, and Reintegration, ed. S. Irudaya Rajan. New Delhi: Routledge India.

Echeverri-Gent, John and Kamal Sadiq, eds. 2020. Interpreting Politics: Situated Knowledge, India, and the Rudolph Legacy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD)/World Bank Group. 2023. Remittance Inflows. Updated December 2023. Available online.

Malit Jr., Froilan T. and Gerasimos Tsourapas. 2021. Weapons of the Weak? South–South Migration and Power Politics in the Philippines–GCC Corridor, Global Studies Quarterly 1 (3). Available online.

Sadiq, Kamal. 2017. Postcolonial Citizenship. In The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, eds. Ayelet Shachar, Rainer Bauböck, Irene Bloemraad, and Maarten Vink. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Sadiq, Kamal and Gerasimos Tsourapas. 2021. The Postcolonial Migration State. European Journal of International Relations 27 (3): 884-912. Available online.

---. 2023. Labour Coercion and Commodification: From the British Empire to Postcolonial Migration States. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies: 1-20. Available online.

---. 2023. The Transnational Social Contract in the Global South. International Studies Quarterly 67 (4): sqad088. Available online.

Tsourapas, Gerasimos. 2021. Global Autocracies: Strategies of Transnational Repression, Legitimation, and Co-Optation in World Politics. International Studies Review 23 (3). Available online.

---. 2022. Migration Diplomacy Gets Messy and Tough. Mixed Migration Centre, December 6, 2022. Available online.

World Bank. World Development Indicators. Updated December 19, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Nepal Development Update: October 2023. Kathmandu: World Bank. Available online.