You are here

The World’s Leading Refugee Host, Turkey Has a Complex Migration History

A Syrian woman in Turkey. (Photo: © ILO/Fatma Cankara)

Turkey is the world’s leading refugee-hosting country, giving shelter to approximately 3.6 million forcibly displaced people. This status has been both a source of pride for the country and a crucial geopolitical tool, as Ankara has weighed its humanitarian responsibilities with other obligations. Turkey’s hosting of the current refugee population, almost all of which comes from Syria, represents the latest development in a long and rich migration history, which in the modern era has helped shape the nation since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923.

Its refugee population is in part a testament to Turkey’s unique geographic position straddling Asia and Europe, perched between both continents at a pivotal crossroads. As such, the country has been a significant country of transit for migrants from Asia (including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan) hoping to go west. Since the European refugee and migration crisis of 2015-16, Turkey’s role as a buffer has become central to the European Union’s migration management efforts. This position was made clear with a 2016 agreement between the European Union and Turkey, in which Turkey committed to assist EU efforts to prevent irregular migration to the bloc. In years since, the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been accused of wielding its migration controls as a lever in order to extract concessions from the European Union, which it has been a candidate to join since the late 1990s.

In This Article

Turkish history has not only been one of in-migration and transit migration, however. Turkey had traditionally been viewed as a country of emigration through the 20th century. Expansive guestworker and other labor migration programs brought Turkish nationals across Europe in the decades after World War II, while more recent emigrants have tended to come from a broader cross-section of Turkish society. Attacks against Greeks in Istanbul in the 1950s, conflict in Cyprus, and the coups of 1960 and 1980 were drivers of different waves of emigration. Turkish migrants and their descendants were historically responsible for sending back significant sums in remittances, which had a major impact on Turkey’s economy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s.

On the other hand, emigration has also brought about challenges, as it gave rise to several diasporic and transnational social and political movements organized around religion and ethnicity that seeped back into Turkey. Within Turkey, the country also transitioned from a heavily agrarian model in the early 20th century to an increasingly urban one, as midcentury industrialization led to sizable domestic migration to cities.

The mass migration of Syrian refugees since 2011 briefly helped transform Turkey into a net-immigration country, though Syrians are far from the first group to move to Turkey in large numbers. From 1923 through the mid-1990s, more than 1.6 million people immigrated to Turkey, fleeing unrest and conflict in the Balkans and Iran.

The country’s location at the doorstep of the European Union, early-2000s democratization, economic growth, and Ankara’s efforts to become a regional force through soft power all made Turkey an attractive destination for immigrants and investment, although some of these factors have become more muted in recent years.

Turkey also hosts a sizable population of internally displaced people (IDPs) who are mainly Kurdish in origin and were forced to leave their rural towns either by security forces or the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) in the 1990s. Kurds account for between 12 million and 15 million Turkish residents.

This article, based in part on the author’s two decades of research in Turkey, provides an overview of the country’s present and historical migration trends, with a focus on post-World War II emigration and the recent immigration of Syrians.

Figure 1. Map of Turkey and Surrounding Countries

For most of the 20th century, Turkey was known as the origin of significant post-World War II labor migration to Europe. The movement was started by a major labor recruitment treaty signed with West Germany in 1961, as well as a smaller deal with the United Kingdom that same year. Those arrangements were followed by similar agreements throughout the 1960s and 1970s with, in order, Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Sweden, Australia, Switzerland, and Denmark, concluding in 1981 with Norway. This migration had a profound effect on the creation of the Turkish diaspora. There were more than 5 million people with Turkish ancestry in EU Member States as of 2023, according to the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, of which more than 3 million lived in Germany.

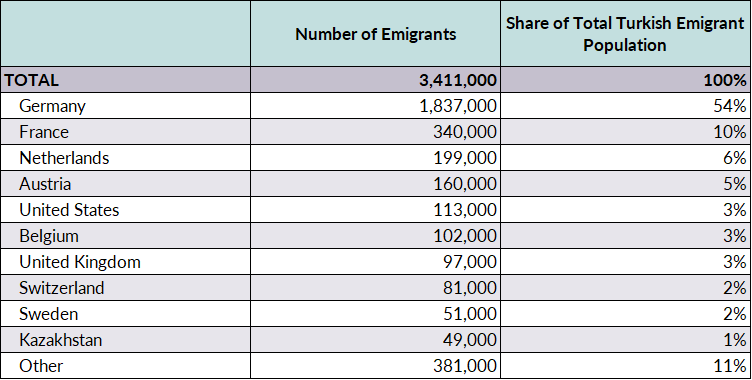

Germany originally signed these guestworker (Gastarbeiter) agreements with the anticipation that the migrants would stay for two years and then return home, typically to rural areas. However, the migrants often extended their stays to benefit from the West’s social, economic, and political development. This dynamic caused some friction, and these programs were discontinued amid the mid-1970s oil crisis and economic turmoil. By the end of the guestworker program in 1973, more than 600,000 Turks had migrated to Germany. Large return migration from Germany followed, with around 300,000 Turks returning in 1984 and 1985. Nonetheless, despite an often inhospitable environment, many former guestworkers decided to stay in Germany, and were joined by subsequent generations of immigrants arriving through family reunification and humanitarian protection routes, rather than labor pathways. As of 2020, Germany was home to more than half of all 3.4 million international migrants from Turkey, according to UN data (see Table 1).

Table 1. Emigrants from Turkey by Country of Residence, 2020

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin,” 2020, available online.

Protests in 2013, centered in Istanbul’s Gezi Park, opposing authoritarian tendencies of the Turkish government and police brutality against environmental groups marked the beginning of a new wave of migration from Turkey to Western Europe, as government dissidents and others left. This new wave is often depicted as heterogeneous, as its composition extends well beyond the traditional cleavages in Turkey. Secular, liberal, highly educated members of the middle class and those from the LGBTQ+ community were among this recent wave, as were members of religious and ethnic minority groups and followers of religious-political factions such as the Gülen movement and others criminalized by the government.

Evolving Views of the Diaspora

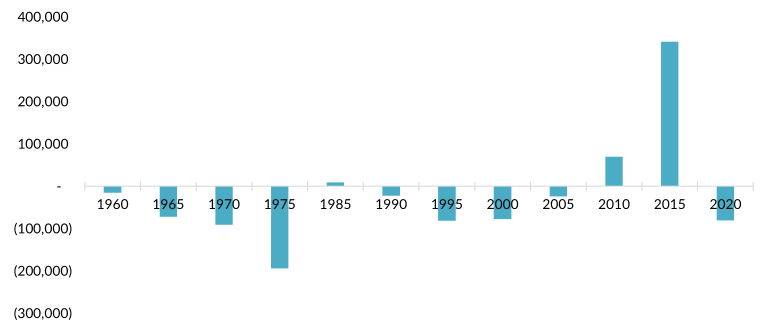

Turkey’s approach to its emigrants has changed by period. During the guestworker era, from the 1960s to the 1980s, emigrants were seen as economic agents providing Turkey with financial remittances, a major source of external financing that helped offset trade deficits. In 1974, remittances sent via formal channels accounted for about 4 percent of Turkey’s gross domestic product (GDP), according to the World Bank (see Figure 2). Yet in recent years, amid economic crises, remittances sent via formal channels have generally shrunk both in absolute terms and relative to GDP, accounting for only about 0.1 percent of GDP in 2022. Documented remittance flows to Turkey have been adversely affected by weak economic conditions. When public confidence in the economy is drastically reduced, migrants might prefer to send remittances through impossible-to-analyze unofficial channels or simply not send any at all. The decline may also be related to the growing number of migrants’ children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren who comprise the diaspora; these individuals may have weaker ties to the homeland and are thus less likely to send remittances.

Figure 2. Remittances to Turkey, Total and as a Share of Gross Domestic Product, 1974-2022

Sources: World Bank, “Personal Remittances, Received (% of GDP),” accessed July 31, available online; World Bank “Personal Remittances, Received (Current US$), accessed October 2, 2023, available online.

The positive view of emigrants changed. From the 1980 coup to the early 2000s, migrants came to be viewed as political agents acting as an extension of the Turkish state to defend its interests abroad against opposition groups and individual critics. This period also marked the beginning of skilled Turks’ migration to new destinations such as the United States and Canada.

Since the early 2000s, as Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) ascended to power, Turkey has embraced market liberalism and European integration, and tended to perceive emigrants as active lobbyists for the state’s interests abroad. Emigrants form a critical voting bloc, and as such are electoral constituents who can be mobilized and incorporated into the national electorate.

Such groups have been activated by the AKP as part of campaign activities. During elections following a quickly aborted 2016 attempt to topple Erdoğan, governments in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and other countries blocked AKP campaigning, on the basis that they disrupted public order. Erdoğan responded by claiming that such policies were “not different from the Nazi practices of the past.” Those comments worsened relations with EU Member States.

A Complex Relationship with the European Union

Tensions have continued to ripple and intersect with Turkey’s growing role as a buffer state for the European Union, which faced the arrival of 2 million asylum seekers in 2015 and 2016, many via Turkey. In March 2016, the bloc struck a deal with Turkey to return migrants crossing in irregular fashion to the Greek islands from Turkey. In exchange, the European Union agreed to help Turkey accommodate and integrate Syrian refugees and resettle them in EU Member States on a one-to-one basis, return to discussions about Turkey’s accession to the European Union, and make other concessions.

Rights advocates have criticized the 6-billion-euro deal, alleging that Turkey is not a truly safe place for refugees and that the agreement has made it harder to protect vulnerable individuals. But leaders have tended to stand by it. Both sides have also accused the other of failing to live up to tenets of the deal, although its central premise has held and been an inspiration for similar EU migration management pacts with other countries.

Importantly, Turkish officials have seemed to recognize their position as holding critical leverage over the European Union and have at times threatened to change policy or allow large numbers of refugees to cross into the West. Just a couple days prior to the first anniversary of the Turkey-EU deal in March 2017, amid a dust-up over AKP campaign activities in Europe, Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu threatened to send to Europe “15,000 refugees each month.” In 2020, during another moment of heightened tensions just before the COVID-19 pandemic erupted in March, Turkish authorities briefly carried through on the threat, temporarily allowing thousands of migrants to leave Turkish soil and pass into Greece.

From a Country of Emigration to One of Immigration

Anatolia, Turkey’s large West Asian peninsula, has been exposed to several migration periods since the Byzantine era when Constantinople (now Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire. Jews, dissident nationalists, and others fleeing persecution in Europe came to the empire in droves over the centuries, as did traders, scholars, and a host of other migrants. The country became increasingly Muslim around the turn of the 20th century, when the Ottoman Empire shrank rapidly, and as Circassian and Crimean Muslims were exiled from the Russian Empire in the late 1800s. The founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923 coincided with the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Turks from Eastern Europe, as Turkish leaders proactively sought to form a national identity for their new country.

In modern times, the first wave of refugees to arrive in Turkey was from Iran, following the 1979 revolution. As many as 1.5 million Iranians entered Turkey in the years after the revolution, typically bound for other parts of the world, but some remained through the 1980s and a minority eventually became Turkish citizens. Approximately 60,000 Kurds escaped into Turkey from Iraq in 1988, and about 500,000 did the same in 1991. Bulgaria’s “Revival Process”—an assimilation campaign against minorities—which started in 1984 saw almost 310,000 ethnic Turks traveling to their ancestral homeland, especially in 1989. And during the Balkan wars, Turkey granted asylum to 25,000 Bosnians and 18,000 Kosovars.

Its geographical location has made Turkey a crucial waystation on irregular migration routes towards Europe, especially for migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan since the 1990s. At the same time, Turkey has been a country of destination for immigrants mainly from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, who see the country as a gateway to a new life and a stepping-stone to employment in the West.

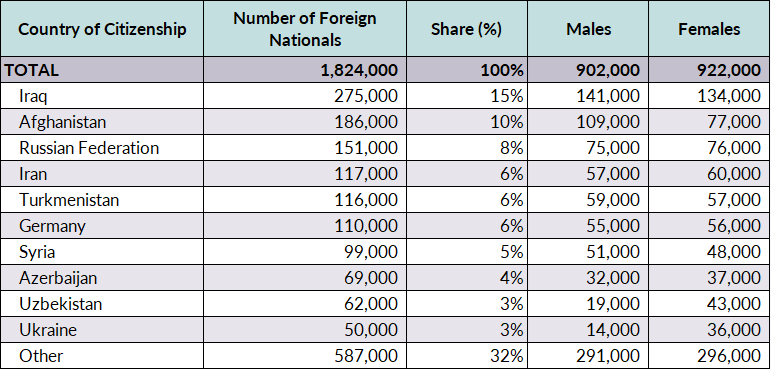

The democratization and Europeanization of Turkey in the early 2000s, along with huge Syrian arrivals, briefly caused a period of positive net migration (see Figure 3). However, since the 2013 Gezi protests, an increasing number of young, skilled people have left to escape Turkey’s rising Islamization, authoritarianism, and de-Europeanization. Since about 2016, more migrants have left Turkey than have arrived.

Figure 3. Net Migration in Turkey, 1960-2020

Source: World Bank, “World Development Indicators,” updated July 25, 2023, available online.

In line with Turkey´s desire to become a greater regional power, policymakers have authorized visa-free travel with neighboring and nearby countries, since 2005 signing deals with Jordan, Lebanon, Russia, and Syria, among others. At the expense of taking its visa regulations out of alignment with EU legislation and de-Europeanizing its foreign policy, Turkey was motivated by economic gains from more regional integration.

Table 2. Foreign Nationals Residing in Turkey, by Country of Citizenship and Gender, 2022

Note: Data do not include Syrians under temporary protection or individuals with visas or residence permits valid for durations of less than three months.

Source: Turkish Statistical Association (TÜİK), “Türkiye’de ikamet etmeye başladığı yıla, cinsiyete ve vatandaşlık ülkesine göre yabancı uyruklu nüfus, 2022” updated July 24, 2023, available online.

A clear sign of the country’s recent immigration aspirations can be seen in the 2013 Law on Foreigners and International Protection, which is discussed in more detail below. The law was partly designed to attract more well-educated immigrants, including international students, and was an outgrowth of the decade-long process of Europeanizing Turkey’s migration and asylum policies.

Current Population of Refugees and Other Forced Migrants

The Syrian crisis prompted the Turkish government to pivot much of its foreign and immigration policy, ushering in an open-door policy for Syrians. Former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu has described the Arab Spring as a regional political earthquake. Since the Syrian civil war broke out in 2011, Turkey has provided Syrians with temporary protection, no forced returns to Syria (although it has faced some allegations of reneging on this promise), and unlimited duration of stay. Turkey first introduced a temporary protection regulation in 2014, granting Syrians similar social and civil rights to those of refugees in Western countries. Still, researchers and rights groups have documented cases in which promises of protection were not fulfilled on the ground, as refugee children were barred from schools, adults faced difficulties securing work permission, and other cases.

Initially, Turkey rejected international assistance for its humanitarian efforts, as it wanted to prove that it could deal with the situation on its own. Internationally, accommodating the refugee flow was supposed to be a sign of Turkey’s strength and its status as a model country in the Middle East. But quickly, the demands became unsustainable. Still, the government sought to avoid the perception that all Syrians presented a threat, with Erdoğan and Davutoğlu calling them “guests” and “brothers” who would one day return to their homeland.

Turkey’s approach remains novel in comparison with the worldwide norms for the treatment of refugees—as well as with its past responses to similar refugee movements—that tend to involve a securitization lens and demands for burden-sharing. Turkey’s shift from a security-centred approach to a rather humanitarian one seems related to its assertive foreign policy as well as to the AKP’s Muslim character, which resonates throughout the region. This has allowed Turkey to assert a leadership role in the neighborhood, where it can play mediator and position itself as a leader able to confront humanitarian problems through diplomacy.

However, Turkish leaders mistakenly assumed that the regime of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad would soon collapse and refugees would quickly return to Syria. During the early days of the open-door policy, Turkish officials were estimating that at most 100,000 Syrians would come to Turkey. As the conflict escalated and stretched on for years, the government has been forced to confront a new reality in which Syrian refugees are a permanent fixture.

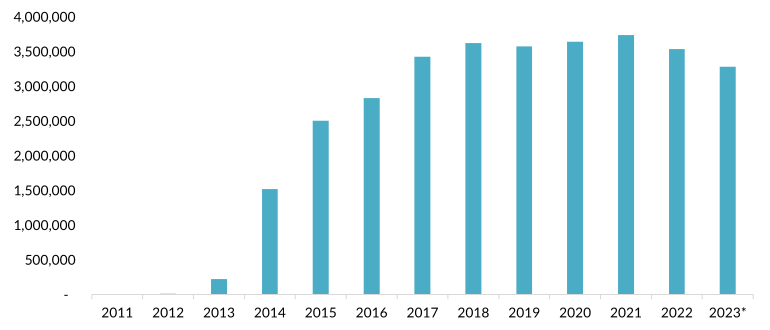

Figure 4. Syrian Refugees in Turkey, 2011-23*

Note: Data for 2023 are as of September 21, 2023.

Source: Turkish Ministry of Interior, Presidency of Migration Management, “Geçici Koruma,” updated September 21, 2023, available online.

With the Syrian war now in its second decade, the number of Syrians in Turkey has levelled off and even begun to decline. According to the Interior Ministry, nearly 527,000 Syrians had returned to Syria as of October 2022.

As of July, more than 3.3 million Syrians lived in Turkey. The vast majority (98 percent) lived in cities, according to the nonprofit Refugees and Asylum Seekers Assistance and Solidarity Association, many in Turkish border provinces. Approximately 201,000 had secured Turkish citizenship.

Box 1. Internal Migration

The increase in Turkey’s population over the last century accompanied increasing urbanization. The relative size of the urban population was rather stable until after World War II, but increased from 25 percent of the total population in 1950 to 44 percent in 1980, 80 percent in 2010, and 93 percent in 2021. The vast majority of rural-to-urban migrants are involved in the informal sector.

Internal movements can be divided into four categories: pre-1950 migration, during which political leaders tried to recruit rural laborers to support the early industrialization process; 1950-85 migration, a period of both rural-urban migration and migration between cities; 1985-2000s, a period of internal displacement driven by armed conflict in the southeast; and more recent movement since February 2023, when two devastating earthquakes destroyed a very large area covering 11 cities in the east and southeast, impacting around 15 million people in Turkey and Syria.

Migration Politics and Policies

Turkey officially does not grant refugee status to those coming from places other than Europe. The 1934 Law on Settlement was adopted for the arrival of ethnic Turks, and was the main law dealing with immigration for decades. It drew a distinction between people of Turkish descent, non-Turkish Muslims, and other immigrants. For instance, immigrant Bulgarian Muslims, Turkomans, Uighurs, and Uzbeks who are ethnically Turkish are identified as “migrants” (göçmen) in official documents as well as in everyday life. Kurds, Syrians, and others from outside Europe who are Muslim but do not have Turkish roots are referred to as “guests” (misafir). And people who fit in neither of the above categories are considered “foreigners” (yabancı).

With the adoption of the Regulation on Asylum in 1994, Turkey began handling asylum cases directly, rather than leaving the responsibility to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The 1994 regulation identified two types of asylum seekers: those granted protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention, and non-European asylum seekers aiming for resettlement in a third country. As refugee determination procedures had previously been carried out by UNHCR, however, the Turkish authorities lacked experience, hence refugee status was often denied when applicants failed to meet arbitrary formal requirements without further evaluation of the merits.

Since the late 1990s, Turkish authorities have worked to sign readmission agreements with several countries of origin and destination. UNHCR has played a central role in this process, especially in Turkey´s current asylum policy. In addition to being the main agency overseeing Turkish asylum policy and ensuring the resettlement of refugees from Turkey during the Cold War, it was responsible for providing basic assistance and accommodation for asylum seekers and refugees in Turkey. However, relations between Turkey and UNHCR gradually worsened after the massive entry of refugees into Turkey following the end of the Gulf War in 1991. Deteriorating security conditions in southeastern Turkey resulting from the activities of the PKK adversely influenced Turkish officials´ attitude towards asylum seekers entering irregularly, as reflected in the 1994 Asylum Regulation. The government briefly ceased cooperation with UNHCR, and initial implementation of the regulation led to criticism from human-rights and refugee advocates.

The Law on Foreigners and International Protection

Refugee protection in Turkey has typically been ad hoc, with authorities offering different treatment by location. The 2013 Law on Foreigners and International Protection is the first domestic law regulating asylum practices, representing a vast step forward towards the transformation and regulation of asylum and migration since ratification of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Management of the Turkish asylum system was taken over by the Ministry of Interior and a standardized practice was established across the country.

Among other things, the law seeks to better integrate foreign-born workers, such as by making it easier for foreign students and refugees with legal status to obtain work permits. And it clarifies that long-term residents including refugees can obtain permanent residence.

EU Discussions

As part of its complicated efforts to join the European Union, Turkey since 2000 has been forced to balance the bloc’s demand that it tighten its entry regime with the economic and tourist benefits that come from a liberal visa policy. While Turkey has increasingly added visa requirements for nationals of more than 20 countries, many can still obtain visas on arrival. The European Union has also sought for Turkey to apply a uniform visa policy towards all EU citizens and tighten its eastern borders with Armenia, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, and Syria.

The European Union’s impact is very visible in the readmission agreements Turkey signed with 15 countries to return their nationals. Despite the ongoing asymmetrical character of Turkey-EU relations, Turkey has transformed its migration and asylum system in the last decade and largely harmonized it with EU law. Combating irregular migration has been a part of this process. A readmission agreement with the European Union was signed in December 2013 and could be seen as part and parcel of the country’s efforts to become a Member State of the union; consequently, it is directly linked to the country’s aim for a visa-free regime for its citizens visiting EU Member States. Three years after the signing of the readmission agreement, the EU-Turkey refugee statement reiterated both sides’ support and intention for Turkish citizens to have the right to visa-free travel into the European Union. However, the failed coup attempt in July 2016, followed by a two-year state of emergency, interrupted the visa liberalization process.

Irregular migrants and Syrians in Turkey continue to be an instrument of bargaining between Turkey and the European Union. In 2020, Turkey announced it would open its borders to let refugees head towards the bloc, prompting buses, taxis, and cars full of asylum seekers to speed towards the border with Greece. In the back and forth that followed, EU leaders offered 500 million euros to support Turkey and announced that they would reconsider restarting the visa liberalization and visa facilitation talks. After meetings in Brussels, Erdoğan called for the borders to close once again. Clearly, the incident paid dividends for Turkey’s foreign policy objectives, at least for the short term, although many migrants caught in the middle have paid a higher price.

Turkey’s long-sought accession to the European Union suffered another blow in September 2023, when the European Parliament adopted a report calling for the European Union to explore a “parallel and realistic framework” with Turkey that falls short of EU accession unless Turkey takes a “drastic change of course.” Erdoğan responded by raising the prospect that Turkey could abandon its EU membership bid and “part ways” with the European Union.

Issues on the Horizon

As it hosts the most refugees in the world, Turkey is likely to continue to struggle with accommodating them, particularly amid increasing societal and political polarization and following devastating earthquakes in early 2023.

Since the early days of the mass migration of Syrians, the AKP government has embraced an Islamic term, Ansar spirit, referring to the people who supported the Prophet Mohammad and accompanying Muslims migrating from Mecca to Medina. Following the implementation of the temporary protection regulation, national approaches have begun to recognize the potentially permanent nature of Syrians’ stay, as evidenced by the offering of work permits in early 2016, incorporation into public schools, creating quotas for Syrian students in higher education institutions, and granting them citizenship.

However, discourse about refugees’ return has become more widespread since 2018, as hostility against Syrians escalated amid socioeconomic and political unrest. Researchers and rights groups have documented cases in which large numbers of refugees were pressured to return to Syria, particularly in the weeks surrounding the 2023 presidential election. The change in discourse has also fostered hostile sentiments against the refugees, leading to further exploitation and placing them in precarious situations in the labor market. Refugees have increasingly become vulnerable because they have been perceived as cheap labor. The COVID-19 pandemic and earthquakes have worsened the situation of refugees—as well as native-born Turkish citizens. And the near future is likely to unfold in ways that may lead to further obstacles for migrants.

A key challenge is that local municipalities lack administrative capacity and adequate resources to integrate arrivals, leaving them with few legal tools to formulate and implement policies. Municipal authorities do very little to challenge national immigration regimes that are increasingly marginalizing Syrians and irregular migrants. City and local district sanctuary policy is also limited by jurisdictional mismatch between governments and neoliberal competition for services.

Turkey is geographically and strategically located in a very fragile zone that is exposed to flows of people across continents, as well as to various environmental and demographic challenges including deforestation, drought, depopulation, aging, and lack of investment in rural and mountainous areas. These challenges became all the more pressing during the pandemic, as agricultural production declined and it became obvious that Turkey was no longer agriculturally self-sufficient.

Given these geographical, environmental, economic, and demographic constraints, policymakers in Turkey could consider more welcoming strategies with regard to migration and integration, using a rights-based approach rather than religious and political forms of benevolence. Turkey’s long and storied history has featured virtually every type of migration, and it is only likely that its future will be just as defined by the movement of people as its past.

Sources

Abadan-Unat, Nermin. 2011. Turks in Europe: From Guest Worker to Transnational Citizen. New York: Berghahn Books.

Adaman, Fikret and Ayhan Kaya. 2012. Social Impact of Emigration and Rural-Urban Migration in Central and Eastern Europe: Turkey. Cologne: European Commission Director General of Employment, Social Affairs, and Inclusion. Available online.

Aksel, Damla. 2019. Home States and Homeland Politics: Interactions between the Turkish State and its Emigrants in France and the United States. London: Routledge.

Arkılıç, Ayca. 2020. Empowering a Fragmented Diaspora: Turkish Immigrant Organisations’ Perceptions of and Responses to Turkey’s Diaspora Engagement Policy. Mediterranean Politics 27 (5): 1–26. Available online.

Aydemir, Nermin. 2022. Framing Syrian Refugees in Turkish Politics: A Qualitative Analysis on Party Group Speeches. Territory, Politics, Governance 11 (4): 658-76.

Brubaker, Rogers. 2017. Between Nationalism and Civilizationism: The European Populist Moment in Comparative Perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 40 (8): 1191-226.

Castles, Stephen and Mark J. Miller. 2009. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. London: Guilford Press.

Davutoğlu, Ahmet. 2010. Turkey’s Zero-Problems Foreign Policy. Foreign Policy, May 20, 2010. Available online.

---. 2013. Dışişleri Bakanı Sayın Ahmet Davutoğlu’nun Diyarbakır Dicle Üniversitesinde Verdiği “Büyük Restorasyon: Kadim’den Küreselleşmeye Yeni Siyaset Anlayışımız” Konulu Konferans, 15 Mart 2013, Diyarbakır. March 15, 2013. Available online.

Deutsche Welle. 2020. Turkey Wants a New Refugee Deal in March. Deutsche Welle, March 10, 2020. Available online.

Dimitriadi, Angeliki and Ayhan Kaya. 2021. EU Turkey Relations on Migration: Transactional Partnership. In Turkey and the European Union: Key Dynamics and Future Scenarios, eds. Beken Saatcioglu and Funda Tekin. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

Elitok, Seçil Paçac. 2019. Three Years On: An Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal. MiReKoc Working Papers, Istanbul, April 2019. Available online.

Erdoğan, Murat. 2015. Türkiye’deki Suriyeliler. Istanbul: Istanbul Bilgi University Press.

Erdoğan, Murat and Ayhan Kaya, eds. 2015. 14. Yüzyıldan 21. Yüzyıla Türkiye’ye Göçler. Istanbul: Istanbul Bilgi University Press.

European Commission. 2015. European Agenda on Migration. COM/2015/240 final. Available online.

---. 2015. Memo: EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan. MEMO/15/5860. October 15, 2015. Available online.

---. 2016. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the State of Play of Implementation of the Priority Actions under the European Agenda on Migration. COM/2016/85 final. Available online.

---. 2016. Managing the Refugee Crisis: EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan. Implementation Report. Brussels: European Commission. Available online.

Frontex. 2015. Risk Analysis Report: Western Balkans Quarter 2 April-June 2015. Warsaw: Frontex. Available online.

Gökalp Aras, N. Ela and Zeynep Şahin-Mencutek. 2015. The International Migration and Foreign Policy Nexus: The Case of Syrian Refugee Crisis and Turkey. Migration Letters 12 (3): 193-208. Available online.

González Levaggi, Ariel. 2015. Forced Humanitarianism: Turkey’s Syrian Policy and the Refugee Issue. Caucasus International 5 (1): 39-49. Available online.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2016. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics and the Real Life of States, Societies and Institutions. New York: Routledge.

Hönekopp, Elmar. 1990. Zur beruflichen und sozialen reintegration türkischer Arbeitsmigratiten in Zeitverlauf. Nuremberg, Germany: Bundesanstaltfuer Arbeit Institut für Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung.

İçduygu, Ahmet. 2003. Irregular Migration in Turkey. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM). Available online.

---. 2009. International Migration and Human Development in Turkey. UN Development Program, Human Development Research Paper 2009/52, New York, October 2009. Available online.

---. 2015. Turkey’s Evolving Migration Policies: A Mediterranean Transit Stop at the Doors of the EU. Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Working Paper 15/31, Rome, September 2015. Available online.

İçduygu, Ahmet and Damla B. Aksel. 2013. Turkish Migration Policies: A Critical Historical Retrospective. Perceptions 18 (3): 167-90. Available online.

Inalcik, Halil. 1994. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600. London: Phoenix Press.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2015. Addressing Complex Migration Flows in the Mediterranean: IOM Response Plan, Spotlight on South-Eastern Europe. Vienna: IOM Regional Office for South-Eastern Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Available online.

Kale, Başak, Angeliki Dimitriadi, Elena Sanchez-Montijano, and Elif Süm. 2018. Asylum Policy and the Future of Turkey-EU Relations: Between Cooperation and Conflict. FETURUE Working Paper 18, Cologne, April 2018. Available online.

Karaçay, Ayşem Biriz. 2017. Shifting Human Smuggling Routes Along Turkey’s Borders. Turkish Policy Quarterly 15 (4): 97-108.

Kaya, Ayhan. 2009. Islam, Migration and Integration: The Age of Securitization. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

---. 2013. Europeanisation and Tolerance in Turkey: The Myth of Toleration. London: Palgrave.

---. 2018. Turkish Origin Migrants and their Descendants: Hyphenated Identities in Transnational Space. London: Palgrave.

---. 2020. Migration as a Leverage Tool in International Relations: Turkey as a Case Study. Uluslararasi Iliskiler 17 (68): 21-39. Available online.

---. 2023. The Neoliberal Face of the ‘Local Turn’ in Governance of Refugees in Turkey: Participatory Action Research in Karacabey, Bursa. Journal of International Migration and Integration, Special Issue on Welcoming Spaces: 1-28. Available online.

Kaya, Ayhan and Ferhat Kentel. 2004. Euro-Turks: A Bridge, or a Breach, between Turkey and the European Union? Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies. Available online.

Kirişçi, Kemal. 2004. Asylum, Immigration, Irregular Migration and Internally Displacement in Turkey: Institutions and Policies. Euro-Mediterranean Consortium for Applied Research on International Migration working paper, European University Institute, Florence, March 2004. Available online.

---. 2011. Turkey’s “Demonstrative Effect” and the Transformation of the Middle East. Insight Turkey 13 (2): 33-55. Available online.

---. 2014. Syrian Refugees and Turkey’s Challenges: Going Beyond Hospitality. Washington DC: Brookings Institution. Available online.

Koc, Ismet and Isil Onan. 2004. International Migrants’ Remittances and Welfare Status of the Left-Behind Families in Turkey. International Migration Review 38 (1): 78-112.

Koser Akcapar, Sebnem. 2010. Re-Thinking Migrants’ Networks and Social Capital: A Case Study of Iranians in Turkey. International Migration 48 (2): 161–96. Available online.

Mandel, Ruth. 2008. Cosmopolitan Anxieties: Turkish Challenges to Citizenship and Belonging in Germany. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Maritato, Chiara. 2021. Islam, the Homeland, and the Family: Diyanet’s Narrative and Practices Aimed at Shaping a Loyal Muslim Turkish Diaspora. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 21 (2): 121-38.

Mitrovic, Olga. 2015. Used During the Balkan Crises, the EU’s Temporary Protection Directive May Now Be a Solution to Europe’s Refugee Emergency. London School of Economics blog post, December 22, 2015. Available online.

Nurtsch, Ceyda. 2019. ‘New Istanbul’ in Berlin: Turkish Brain Drainers versus Guest Workers. Qantara.de, March 6, 2019. Available online.

Oezcan, Veysel. 2004. Germany: Immigration in Transition. Migration Information Source, July 1, 2004. Available online.

Öktem, Kerem and Karabekir Akkoyunlu. 2018. Exit from Democracy: Illiberal Governance in Turkey and Beyond. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Oltermann, Philip. 2017. Erdoğan Ratchets Up Anti-Dutch Rhetoric Despite German Verbal Ceasefire Plan. The Guardian, March 15, 2017. Available online.

Özden, Şenay. 2013. Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Florence: Migration Policy Centre. Available online.

Özyürek, Esra. 2014. Being German, Becoming Muslim: Race, Religion, and Conversion in the New Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pusch, Barbara and Julia Splitt. 2013. Binding the Almancı to the “Homeland”- Notes from Turkey. Perceptions 18 (3): 129-66. Available online.

Refugees Association. 2023. Number of Syrians in Turkey July 2023. August 22, 2023. Available online.

Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. N.d. Turkish Citizens Living Abroad. Accessed October 30, 2023. Available online.

Şahin-Mencütek, Zeynep, N. Ela Gökalp-Aras, Ayhan Kaya, and Susan Beth Rottmann. 2023. Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Between Reception and Integration. Switzerland: IMISCOE Springer Press. Available online.

Schinkel, Willem. 2018. Against ‘Immigrant Integration’: For an End to Neoliberal Knowledge Production. Comparative Migration Studies 6 (31): 1-17. Available online.

Seeberg, Peter. 2017. Managing the Refugee Crisis: New Approaches. IEMed. Mediterranean Yearbook 2017. Available online.

Şenay, Banu. 2013. Beyond Turkey's Borders: Long Distance Kemalism, State Politics and the Turkish Diaspora. London: I.B. Tauris.

Slominski, Peter and Florian Trauner. 2018. How Do Member States Return Unwanted Migrants? The Strategic (Non-)Use of ‘Europe’ during the Migration Crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 101-18.

Toygür, İlke and Bianca Benvenuti. 2016. The European Response to the Refugee Crisis: Angela Merkel on the Move. Istanbul Policy Center-Sabancı University-Stiftung Mercator Initiative working paper, Istanbul, June 2016. Available online.

Turhan, Ebru. 2016. Europe’s Crises, Germany’s Leadership and Turkey’s EU Accession Process. CESifo Forum 2/2016: 25-29. Available online.

Turkish Statistical Association (TÜİK). 2023. Türkiye’de ikamet etmeye başladığı yıla, cinsiyete ve vatandaşlık ülkesine göre yabancı uyruklu nüfus, 2022. Updated July 24, 2023. Available online.

Vukasinovic, Janja. 2011. Illegal Migration in Turkey EU Relations: An Issue of Political Bargaining or Political Cooperation? Journal on European Perspectives of the Western Balkans 3 (2): 147-66.

Wintour, Patrick and Helena Smith. 2020. Erdoğan in Talks with European Leaders over Refugee Cash for Turkey. The Guardian, March 17, 2020. Available online.