You are here

Roxham Road Meets a Dead End? U.S.-Canada Safe Third Country Agreement Is Revised

A border checkpoint between Canada and the United States. (Photo: iStock.com/mphillips007)

Amid a rise in unauthorized crossings at the U.S.-Canada border, the Canadian and U.S. governments over the past year quietly agreed to revisions to the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) to address the practice of individuals crossing without authorization to request asylum in each other’s country. By extending the agreement to the entire 5,525-mile border, the two governments are seeking to put a halt to people trekking to Roxham Road, a rural path that has drawn international headlines as an unofficial crossing for those wanting asylum in Canada.

While revision of the STCA was sought by the government of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the intent of the change—to disincentivize unauthorized border crossings—matches the United States’ own recent asylum policy shifts at the U.S.-Mexico border. Thus, for the United States, there is now a convergence in its border policies at its southern and northern borders.

Changes to the STCA, which were secretly agreed in 2022, were announced on March 24 during U.S. President Joe Biden’s first official visit to Canada and took effect that midnight. With most northbound unauthorized border crossers headed to Quebec, the Trudeau government had been facing growing demands from provincial authorities to address the rising numbers of arrivals.

Implemented in 2004, the STCA mandates that asylum seekers from abroad make their claim in the first of the two countries they reach. It was built on the assumption that both Canada and the United States, with robust asylum systems, are safe destinations for all asylum seekers. As originally negotiated, the requirement applied only to crossings at ports of entry, and not between, thus creating the loophole that led to Roxham Road becoming an unofficial entry point for a growing number of asylum seekers from around the world—and a flashpoint in Canadian domestic politics. More than 39,500 asylum seekers entered Canada last year via unofficial crossings—a more than eightfold increase over the 4,200 in 2021—the vast majority at Roxham Road.

The new STCA modification makes migrants who cross the U.S.-Canada border without authorization ineligible for asylum and other humanitarian protections if they are apprehended or present themselves to authorities within 14 days of crossing. Instead, they are turned back to the country they crossed from, to seek protection there. In conjunction with the alteration, Canada has committed to legally admit 15,000 additional migrants from the Western Hemisphere, without providing details about the admissions pathway.

The announcement of the modified STCA surprised many watchers in the two countries, especially after it was revealed that the expansion had been agreed back in spring 2022. The change was kept secret while both countries prepared the legal framework for implementation, so as not to spur a rush to the border in either direction.

Proponents of the STCA revision contend that it will remove the incentive the original agreement created for irregular border crossings, relieve pressure on Canada’s asylum system, and reduce the burden on public and private services in Quebec, thus lowering the political tension between the province and the national government. In fact, the number of migrants caught crossing into Quebec dropped from about 1,000 per week in December through February to about 100 per week in the first two weeks after the change was made. However, critics argue that the United States is not a safe destination for all migrants who seek asylum—a contention currently before Canada’s Supreme Court—and that the changes will push border crossers to more dangerous locations where they can cross undetected.

The expansion of the STCA comes just before proposed changes at the U.S.-Mexico border will go into effect—expected to coincide with the lifting of the pandemic-era Title 42 expulsions policy on May 11. Beyond disincentivizing irregular crossings, the two developments mark a shift in U.S. asylum policy toward greater reliance on neighboring countries and more restricted access to U.S. protection. Under the southern border plans, non-Mexican migrants arriving without authorization between U.S. ports of entry will be presumed ineligible for asylum if they did not apply first in Mexico and were denied. While falling short of a safe third country agreement, this move would shift some protection responsibility to Mexico, just as the STCA with Canada shifts responsibility northward.

This article reviews the creation of the Safe Third Country Agreement, legal challenges to the accord, its recent revision, border crossing trends, and the evolution of asylum policy at both borders.

The Origins of the Asylum Accord

The original U.S.-Canada Safe Third Country Agreement was signed in 2002 and implemented in December 2004, capping more than a decade of negotiations and asylum law developments in both countries. The call for the agreement came originally from Canada, but after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States it was seen to be mutually beneficial.

In Canada, concerns about the burden of asylum claims emerged when the Supreme Court of Canada in 1985 established asylum seekers’ right to an oral hearing of their protection claims before being removed. The court’s ruling led to a mounting asylum backlog, which incentivized 1987 legislation reforming Canada’s treatment of asylum seekers. Among other changes, the law gave the government the right to return asylum seekers to an intermediate safe state, to have their claims heard there.

The United States and Canada began discussing a safe third country agreement in the early 1990s, but finalization of a 1995 draft was delayed by asylum law debates in both countries. The United States, via a 1995 regulation, allowed adjudicators to deny asylum claims where asylum and other protections were available in a third country. This bar was codified in the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act in 1996, which allows the United States to return asylum seekers to a third country with which it has an agreement, so long as the individuals would not face persecution on protected grounds there and they could access “full and fair” asylum procedures.

The 9/11 attacks revived the U.S.-Canada negotiations. In December 2001, the two countries signed the Smart Border Declaration to enhance border security. That agreement included migration-related initiatives, including an intention to develop the STCA, which the countries signed in December 2002.

Until 2019, neither the United States nor Canada pursued safe third country agreements with other countries. In fact, when the original STCA was being developed, U.S. officials asserted they had no intention to seek similar agreements with other countries. As explained below, in 2019, the United States signed agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to return asylum seekers there; only the Guatemala agreement was ever used, and these agreements have been ended. Canada has not signed a safe third country agreement with any other country.

Operation of the STCA

The United States implements the STCA with Canada primarily through the expedited removal process. Migrants arriving at the northern U.S. border without prior authorization are placed into expedited removal unless they can prove they have been in the United States for at least 14 days. Once in expedited removal, individuals asserting a protection claim receive a threshold screening where an asylum officer determines whether they are eligible for an exception to the STCA. If not, and a supervisor concurs, the asylum seekers are turned back to Canada to seek protection there. These determinations cannot be reviewed by an immigration judge. If found to be eligible for an exemption, migrants get a credible fear screening for their asylum claim and, depending on the outcome, are either placed into immigration court proceedings or removed. Migrants who entered without authorization and can demonstrate at least 14 days of U.S. presence are placed into removal proceedings in immigration court rather than in expedited removal.

Similarly, for migrants found crossing into Canada, Canadian immigration authorities conduct a threshold screening interview. Those deemed ineligible for an STCA exemption are returned to the United States; those who qualify can file for asylum at a port of entry or online. Migrants wishing to contest a finding of ineligibility can request leave to seek review by the Federal Court of Canada. Those found eligible to apply for asylum have their claims referred to the Immigration and Refugee Board.

Revision of the STCA

The fact that the STCA expansion beyond ports of entry applies only to those who make protection claims within 14 days of arrival seems to come from the United States’ intention to implement the revised agreement through the use of expedited removal. Current U.S. regulations limit the use of expedited removal to migrants encountered within 100 miles of the border who cannot prove at least 14 days of U.S. presence.

The modified STCA, like the original, grants exceptions in four types of situations: unaccompanied children, those with a broad set of qualifying family members in the destination country, individuals with a valid visa to the destination country or who can enter through a visa waiver program, and those who should be exempted in the public interest (at the discretion of each government and, in Canada’s case, those who would face the death penalty in the United States or elsewhere).

The STCA was originally applied only at ports of entry for practical considerations, based on international experience. The European Union’s Dublin Regulation allows for the return of asylum seekers to another signatory country through which they passed, to seek asylum there, on the principle that asylum seekers should apply for asylum in the first safe country they reach. Dublin implementation has been challenging due to difficulties proving migrants’ travel itineraries, leading to complicated negotiations between countries over responsibility for individual asylum claims. Applying the U.S.-Canada STCA only at ports of entry avoided the Dublin complications, the State Department said during a 2002 congressional hearing, because government officials would have visual confirmation that a migrant was crossing from one country to the other.

Rising Border Crossings Usher in STCA Modification

Northward unauthorized crossings of the U.S.-Canada border have always been more common than southward ones, but rising numbers since 2017 provided the main impetus for revising the STCA. While the U.S. economy remains a pull factor for many migrants, faster access to work authorization, greater access to social services, and higher asylum grant rates for some national-origin groups make Canada an appealing destination.

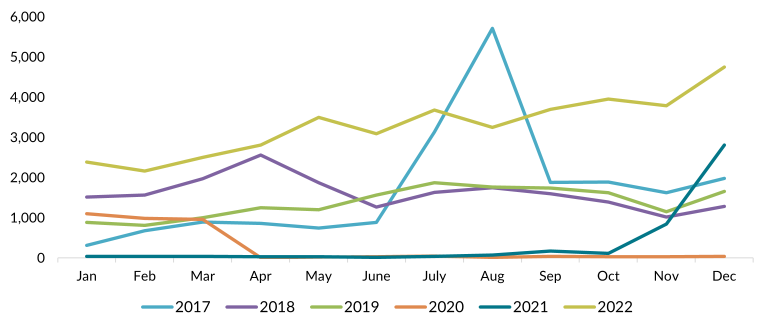

Leading up to the signing of the original STCA, between 8,000 and 13,000 asylum claimants a year passed through the United States to Canada, while typically just a few hundred sought asylum via the reverse trip. Asylum claims at Canadian ports of entry fell after the agreement was signed, to the level of 3,000-7,000 a year in 2011 through 2016. However, as the agreement inadvertently incentivized crossings between ports of entry, unauthorized crossings began to rise in 2016. Border officials in Quebec had intercepted fewer than 50 unauthorized crossers per month between 2011 and 2015, but that number rose to 300 in December 2016. In August 2017 alone, nearly 6,000 migrants were intercepted entering Canada, almost all in Quebec. Between 2017 and 2022, 96 percent of unauthorized encounters took place in Quebec.

The 2017 spike in arrivals was principally driven by the northward migration of some Haitians who had lived in the United States for extended periods of time. In May 2017, the U.S. government announced its intention to end Temporary Protected Status for about 46,000 Haitians. Fearing a loss of U.S. legal status, Haitians headed to French-speaking Quebec, in hopes of obtaining protection there. Most went through Roxham Road, with crossings routinized as taxis provided regular service from the bus station in Plattsburgh, NY to a cul-de-sac near the informal border crossing.

Another upswing in northward border crossings occurred in spring 2018, also principally at Roxham Road. This time it was driven by Nigerians fleeing difficult economic and security conditions, traveling on U.S. tourist visas that were easier to obtain than Canadian ones.

Irregular migrant crossings fell during the COVID-19 pandemic, but climbed again in late 2021 and 2022, exceeding 39,500 in 2022, more than double the 2019 level.

Figure 1. Migrant Interceptions by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police between Ports of Entry, 2017-22

Source: Government of Canada, “Refugee Claims by Year,” updated February 20, 2023, available online.

The sharp spike in crossings led to rising complaints in Quebec about the costs of supporting migrants awaiting their asylum hearings. Provincial officials pushed the national government to close Roxham Road, designate it an official crossing point so the STCA could hold force, or expand the agreement to apply between ports of entry. The Trudeau government began relocating some asylum seekers to other parts of Canada. Still, irregular border crossings became a hot-button issue and a source of ongoing tension between Quebec and the federal government.

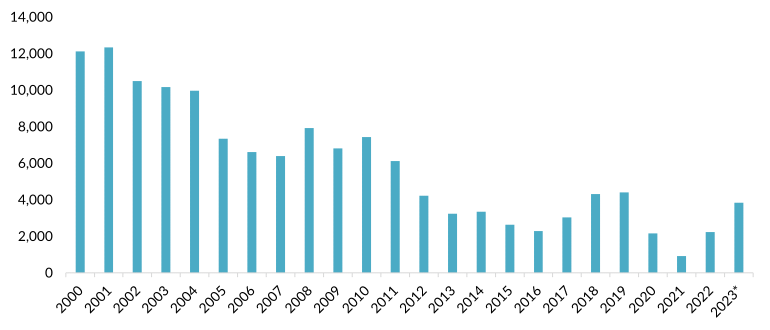

From the U.S. side, the northern border attracted political attention only recently, as irregular crossings rebounded after a pandemic low. Apprehensions between ports of entry were relatively high in the early 2000s, exceeding 12,000 per year, but fell to an average of just over 3,000 per year in fiscal years (FY) 2012-19. After a pandemic dip, the numbers rose quickly, reaching 3,800 in the first six months of FY 2023, leading to calls for more enforcement. In February, 28 House Republicans formed a Northern Border Security Caucus to raise attention to human and drug trafficking along the northern border. The recent rebound in unauthorized northern border crossings was driven primarily by Mexicans, whom U.S. Border Patrol encountered 1,999 times in the first six months of FY 2023, more than double the 882 a year earlier. In response, the United States began flying migrants from the northern to the southern border for processing under Title 42.

Figure 2. U.S. Northern Border Encounters of Migrants between Ports of Entry, FY 2000-23*

* Fiscal year (FY) 2023 numbers span October 2022 through March 2023.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol, “Nationwide Encounters,” updated April 14, 2023, available online; U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Total Illegal Alien Apprehensions By Month,” FY 2000-FY 2020, accessed April 19, 2023, available online.

Legal Challenges in Canada

The STCA has long been controversial in Canada. Shortly after the agreement was implemented, its legality was challenged by Amnesty International, the Canadian Council for Refugees, and the Canadian Council of Churches, which argued that the United States does not fully comply with the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1984 Convention Against Torture, and thus Canada violated its laws by returning migrants to the United States. They pointed, in particular, to the one-year U.S. time limit on filing asylum claims, low bars for disqualifying asylum seekers who are classified as supporting terrorists, and the fact that domestic violence survivors may not be eligible for asylum. A Canadian federal court upheld the challenge, but the Federal Court of Appeals overturned the ruling, stating that the federal government had met its statutory requirements, and the Canadian Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal.

That left the STCA as settled law in Canada until the same groups brought a fresh challenge in 2017. The litigants argued that changes to U.S. policy under President Donald Trump, including increased use of immigrant detention, rising prosecutions for illegal entry, and the so-called Remain in Mexico policy, among other changes, all undermined access to U.S. protection. A federal court agreed with the argument that the STCA violated Canadian and international law, but the appellate court overturned that ruling. In October 2022, the Supreme Court of Canada heard arguments in the appeal. Its decision, which could affect the original and modified STCA, is pending. The new modifications may have bolstered the challengers’ argument before the court.

Other U.S. Safe Third Country Agreements

In 2019, the United States signed accords with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (officially called Asylum Cooperation Agreements) using the same framework as the U.S.-Canada STCA, allowing U.S. authorities to send asylum seekers to request protection in one of those countries. The only exemptions were for unaccompanied children and those who could demonstrate they were more likely than not to experience persecution or torture in the country where they were to be sent. These agreements came despite serious concerns about the safety for asylum seekers in these countries and the capacity of their asylum systems.

The Guatemala agreement was the only one to be implemented. Between November 2019 and March 2020, U.S. officials sent more than 900 Salvadoran and Hondurans migrants to Guatemala. Only a few reportedly received protection screening there, and most opted not to seek asylum or remain in Guatemala; as of January 2021, none had received asylum. The agreement was paused in March 2020 due to the pandemic, and the Biden administration ended the three agreements after taking office in 2021.

In 2019, the Trump administration hinted at a forthcoming safe third country agreement with Mexico, but the Mexican government insisted no such deal was in the works. Instead, that July, the Trump administration announced that migrants who arrived in the United States after passing through a third country that was a signatory to international refugee agreements, and did not seek to obtain asylum there, would be ineligible for U.S. asylum. This amounted to something like a unilateral safe third country agreement with Mexico. While the rule was initially blocked by lower courts, the Supreme Court allowed it to take effect in September 2019, without ruling on the merits. Ongoing litigation meant the policy was in effect on and off until its use was ended by a court injunction in February 2021.

Bringing the U.S. Borders Closer into Alignment

This January, Biden announced his administration would again implement a policy rendering some who crossed through another country on their way to the United States ineligible for U.S. asylum. This time, the policy will apply only to migrants who arrive without authorization at the Mexico border between ports of entry. Asylum seekers are directed to make appointments to pursue an asylum claim at ports of entry through the CBP One app. This new version of a transit country rule would establish a presumption of ineligibility rather than a ban on those who had transited through Mexico and entered without authorization, and would also have more exemptions. Unaccompanied children, migrants with an acute medical emergency, and those facing an imminent and extreme threat to life or safety or who were victims of severe forms of human trafficking would be exempt from the presumption of ineligibility. Migrants found ineligible for asylum because they passed through Mexico could potentially be eligible for lesser protections under the Convention Against Torture or withholding of removal, if they meet a higher standard of showing they are more likely than not to face persecution or torture in their origin country.

The proposed policy would achieve two main U.S. goals of a safe third country agreement with Mexico: Pushing responsibility for adjudicating many asylum claims on Mexico and disincentivizing irregular migration. However, there is a key difference. Migrants found ineligible for asylum or other protection under the new transit rule would likely be removed to the country they originally fled rather than sent to pursue asylum in Mexico. Critics argue that while Mexico is a signatory to the Refugee Convention, it is not safe due to high rates of crime and kidnapping in many areas, particularly targeting vulnerable migrants. And Mexico’s asylum system, while growing in capacity, received 119,000 applications last year—just a small fraction of the number of unauthorized arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border last year.

Litigation is almost inevitable. If and when this policy change takes effect, migrants at the U.S. southern and northern borders alike will find it difficult to prove their eligibility for U.S. asylum, unless they meet a specific exemption or, at the southern border, they can make an appointment at a port of entry to present their claim there.

STCA Implementation Challenges Ahead

Revising the U.S.-Canada STCA closes what was widely seen as a loophole that incentivized crossings between ports of entry. Roxham Road’s notoriety as an easy journey to seek asylum in Canada led to high numbers of claims, challenging Canada’s asylum adjudication capacity and placing a heavy burden on Quebec and other providers supporting asylum seekers. While most attention was drawn to irregular crossings moving north, the hypothermia deaths of an Indian family in January 2022 and of a Haitian man in January 2023 trying to cross into the United States spotlighted the dangers of unauthorized movement in either direction.

The STCA revision is likely to push migrants to even more remote crossing routes, increasing the risks. In fact, within the first two weeks of the change, eight migrants drowned trying to cross the St. Lawrence River from Canada to the United States. The 14-day limit on asylum claims by irregular border crossers may lead migrants to cross and lay low for two weeks before making a protection claim.

Other safe third country agreements, such as the Dublin system, were predicated on harmonized asylum systems between signatories. The U.S.-Canada accord brings no such harmonization, meaning the fact that some migrants may fare better under Canada’s asylum system than the United States’ seems likely to remain a draw for some. This may be even more the case as the United States restricts access to asylum at its southern border. Planned U.S. changes would place asylum out of reach for many who cross the U.S.-Mexico border without authorization. While some will be subjected to expedited removal and unable to lodge an asylum claim, manpower and detention space limitations may mean that many migrants will still be released into the United States with notices to appear in immigration court, but will be unable to seek asylum in those proceedings as long as the new rule remains in effect. Such migrants, particularly those who believe they have a strong asylum claim, may find a northward journey to Canada a better option for seeking protection.

The planned U.S.-Mexico border changes, along with the revised U.S.-Canada STCA, signals a clear direction in U.S. asylum policy: relying more heavily on neighbors to handle asylum claims for those who traversed those countries first. While Mexico is unlikely to sign a safe third country arrangement with the United States anytime soon, U.S. policy is nonetheless edging towards leaning more on Mexico’s asylum system to share or bear the responsibility for processing the rising number of migrants from around the world reaching North America in search of protection.

The authors thank Viola Pulkkinen, Susan Fratzke, and Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh for their assistance.

Sources:

Canadian Council for Refugees and Amnesty International Canada. 2017. Contesting the Designation of the US as a Safe Third Country. Montréal: Canadian Council for Refugees and Amnesty International Canada. Available online.

Chapman, Cara. 2023. Rejected by Canada, Asylum Seekers Plot Their Next Steps at a Plattsburgh Gas Station. North Country Public Radio. April 19, 2023. Available online.

Chesoi, Madalina and Robert Mason. 2022. Overview of the Canada–United States Safe Third Country Agreement. Ottawa: Library of Parliament. Available online.

Cowger, Sela. 2017. Uptick in Northern Border Crossings Places Canada-U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement under Pressure. Migration Information Source, April 26, 2017. Available online.

Esposito, Anthony and Nelson Renteria. 2019. Mexico Says Dodges Bullet on 'Safe Third Country' Talks with U.S. after Stemming Migrant Flows. Reuters, July 21, 2019. Available online.

Fratzke, Susan. 2019. International Experience Suggests Safe Third-Country Agreement Would Not Solve the U.S.-Mexico Border Crisis. Migration Policy Institute (MPI) commentary, June 2019. Available online.

Government of Canada. 2002. Final Text of the Safe Third Country Agreement. Washington, DC: Government of Canada. Available online.

---. 2022. Final Text of the Additional Protocol to the Safe Third Country Agreement. Ottawa: Government of Canada. Available online.

---. 2023. Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement. Updated March 27, 2023. Available online.

Harrington, Ben. 2020. Safe Third Country Agreements with Northern Triangle Countries: Background and Legal Issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

House Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Immigration, Border Security, and Claims. 2002. United States and Canada Safe Third Country Agreement. 107th Cong., 2nd sess., October 16, 2002. Available online.

Krauss, Clifford and Robert Pear. 2004. Refugees Rush to Canada to Beat an Asylum Deadline. The New York Times, December 28, 2004. Available online.

Martinez, Didi and Julia Ainsley. U.S. Starts Flying Migrants Caught Crossing Canadian Border South to Texas. NBC News, March 23, 2023. Available online.

Masis, Julie. 2017. Way More Migrants Are Now Sneaking Across the US-Canada Border. The World, January 12, 2017. Available online.

Panetta, Alexander. 2023. U.S. Republicans Are Now Warning: Migration from Canada Is a Problem. CBC News, February 28, 2023. Available online.

Pierce, Sarah and Jessica Bolter. 2020. Dismantling and Reconstructing the U.S. Immigration System: A Catalog of Changes under the Trump Presidency. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Shear, Michael D. and Maggie Haberman. 2019. No Secret Immigration Deal Exists with U.S., Mexico’s Foreign Minister Says. The New York Times, June 10, 2019. Available online.

Smith, Craig Damien. Changing U.S. Policy and Safe-Third Country “Loophole” Drive Irregular Migration to Canada. Migration Information Source, October 16, 2019. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). 2019. Implementing Bilateral and Multilateral Asylum Cooperative Agreements under the Immigration and Nationality Act. Federal Register 84, no. 223. November 19, 2019. Available online.

U.S. Representative Mike Kelly. 2023. Reps. Kelly, Zinke Lead 28 House Republicans Announcing 'Northern Border Security Caucus' to Combat Human & Drug Trafficking Along U.S.-Canadian Border. Press release, February 28, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Democratic Staff. 2021. Cruelty, Coercion, and Legal Contortions: The Trump Administration’s Unsafe Asylum Cooperative Agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, A Democratic Staff Report Prepared for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate. Washington, DC: U.S. Senate. Available online.

Walsh, Marieke. 2023. U.S., Canada Kept Migrant Crossing Deal a Secret to Avoid Rush at the Border. The Globe and Mail, March 26, 2023. Available online.

White House. U.S.-Canada Smart Border/30 Point Action Plan Update. Fact sheet, December 6, 2002. Available online.