You are here

Chasing the Dubai Dream in Italy: Bangladeshi Migration to Europe

Bangladeshi migrant workers listen to instructions at a camp near the border of Tunisia and Libya. (Photo: SebDech/Flickr)

In 2017, Bangladeshis suddenly emerged as one of the top migrant groups taking a perilous journey across the Mediterranean to reach European shores, along a route more traditionally frequented by sub-Saharan Africans. More than 8,700 Bangladeshis arrived in Italy by sea between January and August 2017, comprising roughly 9 percent of all maritime arrivals and ranking behind only Nigerians and Guineans, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Most brave this often-deadly journey in search of work, their migration paved by a complex set of factors at origin.

For several decades, Bangladeshis unable to find jobs amid uneven development at home have set out to work in countries that need their labor, primarily in the oil-rich Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region. But increasingly, brutal working conditions combined with an economic slowdown and restrictive government policies toward migrant workers in the GCC are leading some to reroute their Dubai Dream to Europe—though the numbers heading there remain a fraction of overall Bangladeshi emigration. Most arrive in Italy irregularly via Libya, seeking temporary work rather than permanent settlement.

The rising number of Bangladeshis making the journey signals an alarming new trend in the migrant labor industry: the blurring of the line between recruitment and smuggling. Young men—and sometimes women—pursue foreign jobs through recruiters, and in the process, get caught up in smuggling networks. Smugglers are now charging Bangladeshis exorbitant fees for the promise of a visa, passage, and employment in another country. But very often, a journey that begins with promises of a better life abroad turns into a harrowing ordeal involving risky passages and forced confinement. The recruits become trapped by the people who transport them. They travel through unknown lands without knowledge of local languages, and may have handed over passports and other valuables to their recruiters. Unable to escape even if they try, smuggled migrants become victims of trafficking.

This article explores the emerging phenomenon of irregular Bangladeshi migration to Europe, examining the country’s history of labor emigration more broadly, push factors at home, dangers along the journey, and government responses.

A Long History of Labor Migration

Bangladeshis are no strangers to seeking foreign employment, and the United Nations Population Division estimated that more than 7.2 million lived abroad in 2015, representing about 4.5 percent of the country’s population. Nearly 758,000 new workers set off in 2016, a 36 percent jump from a year earlier. Growing numbers of women are also choosing jobs internationally, making up 19 percent of all Bangladeshi foreign workers in 2015.

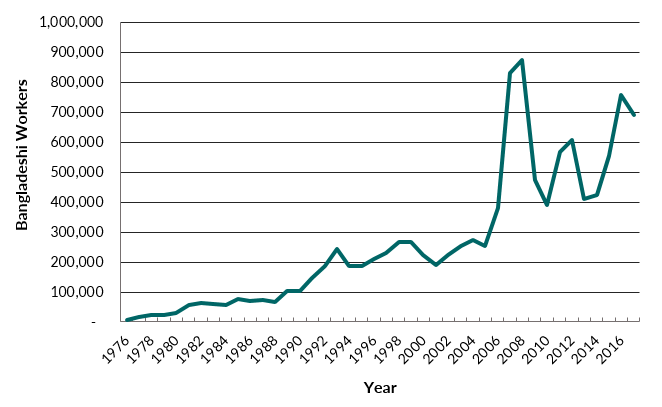

Temporary labor migration from Bangladesh began in the 1970s, intensified by the 1980s, and has continued growing since then. It has figured prominently in the country’s economic strategies, with governments pursuing development plans intended to maximize returns on available human capital. As Bangladesh gained a foothold in the international contract labor market, GCC countries became the primary destinations for workers.

Figure 1. Bangladeshis Newly Employed Abroad, 1976-2017*

* The 2017 data cover January-August.

Source: Bangladesh Bureau for Manpower, Employment, and Training (BMET), “Overseas Employment and Remittances from 1976-2017 (Up to August),” accessed October 4, 2017, available online.

The migrant labor industry—at first well regulated, with well-paying and responsible employers—brought remittances that contributed significantly to the country’s economic growth. It visibly changed the rural economy: The best homesteads typically belonged to families with at least one son working in the Middle East. By the 1980s, many young men aspired to work abroad for a few years and come home with enough money to pave the way for a good life. These men started leaving to work in GCC countries—and eventually, in Malaysia and Singapore—all the while maintaining strong relationships with their families back home.

Today, Bangladesh’s economy continues to rely heavily on remittances. In 2015, the country ranked ninth among top remittance recipients, taking in nearly $15.4 billion—around 8 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP).

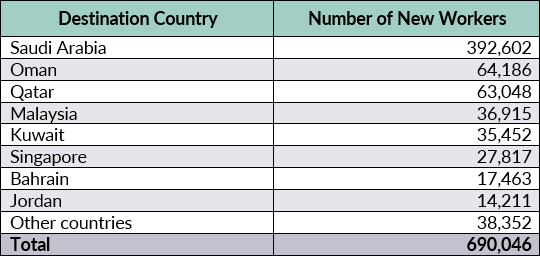

The majority of Bangladeshi migrant laborers still work in the GCC region. Meanwhile, most of the estimated 10 million unskilled and semi-skilled migrants employed in the region are from South and Southeast Asia, primarily Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka, according to a 2009 International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

Table 1. Top Destinations of New Bangladeshi Migrant Workers, 2017*

* The 2017 data cover January-August.

Source: BMET, “Overseas Employment in 2017,” accessed September 18, 2017, available online.

With Malaysia and Singapore growing in popularity as destinations, an additional smuggling route has emerged across the Bay of Bengal, with travel in both directions. As Bangladeshi nationals venture out seeking work in Southeast Asian countries, persecuted Rohingya refugees from Myanmar head toward Bangladesh and Thailand. More than 500,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh since late August 2017 in an attempt to escape violence and persecution at the hands of Myanmar’s army, in what United Nations officials have called a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Bangladeshis also migrate to India, reflecting another trend: migratory movements between low- or middle-income countries. While the numbers are not reflected in official data, India’s government estimated in 2016 that there were some 20 million Bangladeshis living in India illegally, which would make this migration corridor the largest in the world. Some are Hindu refugees, while others are trafficked for sex or forced labor.

Internal migration within Bangladesh has also increased. People from rural villages seek work in cities, due to declining demand for agricultural labor and a need for workers in the urban informal sector. Cities are bursting at the seams, with growing numbers of people arriving to work in the construction, transportation, and ready-made garments industries. Those seeking work are perfect targets for recruiting agencies.

Dalals: Recruiters or Smugglers?

For Bangladeshis, it is almost impossible to get work abroad—legal or otherwise—without a dalal, an agent who promises a visa and employment in exchange for exorbitant fees. Interviews with recently landed Bangladeshi migrants in Sicily reveal that many paid between US $4,000 and $5,000 on average to dalals who promised them work visas, according to IOM—an immense sum considering the average low-skilled worker in Bangladesh earns around $1,070 a year, according to the ILO. The recruiter fees could be as high as $15,000 for Bangladeshis seeking work in Europe, according to 2013 European Union estimates.

Dalals form an intricate, informal network at home, in destination countries, and at points of transfer in between. In Bangladesh, the agents recruit potential migrants, while in Italy, they help unauthorized arrivals apply for visas, and work with migrants and families to secure passage for their dependents.

Workers typically connect with dalals through personal networks. By the time migrants are en route to their destination, they have drained most of their resources to finance the trip. Families dip into their savings, sell assets, or take massive loans to send a child abroad in the hope that he or she will eventually provide for the family in the form of remittances. Very often, workers owe smugglers for these expenses, debts they are expected to repay as they work.

The journey often takes migrant workers from GCC countries or Turkey to Libya; in fact, the more than 4,600 Bangladeshis who arrived in Italy by sea between January and April 2017 departed from Libya. Before journeying across the Mediterranean, many Bangladeshis spent several years in Libya, where traffickers often seize migrants’ travel documents and force them into labor. Some end up in Libyan detention centers, living in horrific conditions.

Since the fall of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi and subsequent unraveling of Libyan governance, violence and difficulty finding employment there have prompted many foreign workers to attempt a further journey to Europe. Between 50,000 and 80,000 Bangladeshis were working in Libya when Gaddafi was ousted in 2011. Most lost their jobs, but only a few had the resources to return to Bangladesh. As Libya has lacked a functional government to control its borders, the Libya-to-Italy corridor has become a lucrative route for smugglers.

Dubai Dream Deferred

Despite the dangers of the journey, increasing unemployment and political instability at home are leading more young Bangladeshis to seek employment abroad, whether in Europe or elsewhere. This path does not always have a happy ending. The men and women who build and maintain the glamorous cities in the GCC region often experience difficult and unsafe working conditions. In many cases they cannot leave, as they are trapped in debt from making the journey and employers confiscate their passports. On average, it takes workers 17 months to recoup their recruiter fees and travel costs to Saudi Arabia, around 11 months for the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Oman, and roughly ten months for Bahrain, Libya, and Qatar.

Unsafe, and sometimes deadly, working conditions exact an even greater toll, typically on young men. In 2016, the bodies of 3,481 dead migrants were repatriated to Bangladesh—a rate of nine and ten arriving daily at the airports, on average.

Beyond harsh working conditions, the economic slowdown resulting from falling oil prices and government policies designed to promote the employment of native-born workers are causing the shine to wear off GCC destinations for some Bangladeshis. Amid its “Saudization” campaign to shift the labor force balance toward Saudi nationals, the Saudi government in 2008 paused the migration of male workers, reinstating visas for Bangladeshis only in early 2017. Because much recruitment of Bangladeshis happens through informal networks and word of mouth, the return of migrants from Saudi Arabia signals to potential recruits that the country is no longer a lucrative option.

Still, international labor markets have become all the more important for young Bangladeshi men who see no future at home. Imagined foreign destinations become a hopeful place. And Europe has emerged as an attractive alternative to the Gulf, at least in people’s thinking.

Destination: Italy

Italy has long been a destination of interest for Bangladeshis. In 2009, 84,000 Bangladeshi immigrants lived in Italy and a report issued that year, the Fifteenth Italian Report on Migration, forecast the number would reach 232,000 by 2030. Many are unauthorized, with estimates ranging from 11,000 to 74,000. Bangladeshis working in Italy are mostly single men who send money home and split their time between the two countries. They are integrated into Italian communities and doing fairly well economically, earning money by running restaurants and selling goods in the streets.

Bangladeshi migration to Italy began in the 1980s and 1990s, when many arrived from other European countries after learning of Italy’s relatively liberal immigration policies. Others have since arrived through family reunification visas. In 2002, Italy passed an immigration law that led to the regularization of more than 700,000 immigrants. The law introduced a quota system that allowed migrants to stay if they could find an employer willing to support their legalization through a complicated bureaucratic procedure. Since 2006, 3,000 Bangladeshis have been able to work in Italy legally under the new law. This prompted an influx of unauthorized entries, under the assumption that they too would be legalized.

But Italy has since modified its policy, reducing visa numbers for Bangladesh and other countries, and it is no longer easy to gain documentation. Meanwhile, smugglers have continued to transport migrants through unauthorized means, most reaching Italy by traveling from Libya to the island of Lampedusa, south of Sicily.

Once in Europe, some Bangladeshis file for asylum. The number of Bangladeshi asylum applications has nearly tripled, from roughly 6,000 for all of Europe in 2008 to more than 17,000 in 2016. Italy received the most asylum applications from Bangladeshis in 2016, with 6,665; followed by France with 3,155 and Germany with 2,655. While some Bangladeshis are able to demonstrate valid grounds for asylum—for example being a member of the persecuted opposition—others are simply looking for a legal way to stay and work. Overall, asylum recognition rates for Bangladeshis were low, around 17 percent on average, compared to 98 percent for Syrians and 61 percent for all nationalities.

Policy Responses at Destination and Origin

The European Union has been pressuring Bangladesh to encourage its unauthorized migrants to return, threatening to impose visa restrictions on Bangladeshi nationals unless the government takes action to repatriate its citizens. The Bangladeshi government planned to finalize procedures for returns by September 2017, though the exact details of the plan were unclear. It has emphasized that while it wants to bring back irregular workers, safe and regular migration channels must be expanded.

Italy has undertaken a number of efforts to curb smuggling in the Central Mediterranean. The Italian government agreed to send naval patrol boats to Libya to support the Libyan coast guard in its fight against human smugglers. It has also engaged in negotiations with local militias to prevent the dispatching of migrant-laden boats—while offering little protection for migrants themselves. And concerned that search-and-rescue efforts mounted by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the Mediterranean are facilitating smuggling, Italy introduced a new code of conduct for NGOs engaged in migrant rescue operations, which includes a ban on sending light signals and transferring migrants to other ships. NGOs, several of which have refused to sign the code, insist that it will lead to more deaths, as their boats have picked up more than one-third of migrants brought to shore in 2017.

Establishing a Framework at Origin to Protect Migrant Workers

As destination countries seek to reduce irregular arrivals, Bangladesh has strengthened its policies for the protection of nationals who deploy abroad. The country has no shortage of mechanisms to protect the rights of those who are formally employed. In 1982, Bangladesh enacted an emigration ordinance to monitor and regulate the departure of migrant workers. The Overseas Employment Policy followed in 2006, to ensure the rights of workers to choose quality employment. Implementation has been ad hoc, however. In 2011, Bangladesh passed the Migration and Overseas Employment Act, which seeks to govern migration by protecting migrant rights. It includes provisions to facilitate emergency return of migrants during crises, crack down on fraudulent practices, and increase recruitment agency accountability.

However, these institutional safeguards have become less effective as recruitment networks have become increasingly complex and difficult to penetrate. Although agencies are primarily based in Dhaka, they recruit through informal agents and subagents throughout the country. More than 10,000 unregistered and unidentified agents operate across Bangladesh, according to the Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit based at the University of Dhaka. Agents inform potential clients about job opportunities, recruit workers, and handle the finances.

The complexity of these networks makes it difficult to identify where formal recruiting ends and smuggling—or trafficking—begins. Smugglers and traffickers are also difficult to track down and prosecute, and the conviction rate for trafficking is extremely low. Between 2011 and 2014, Bangladesh reported just 11 to 15 convictions per year for human-trafficking cases, even as the number of cases lodged against alleged traffickers surged, according to a 2016 UN Office on Drugs and Crime report. The report attributes the low number of convictions to the fact that most laws in this area are recent, and that national criminal justice systems need time and resources to build the expertise to successfully handle human-trafficking prosecutions.

A Way Forward?

Given Bangladesh’s economic and political challenges, it is highly unlikely that the desire to chase the international dream will diminish anytime soon for many Bangladeshis—particularly as long as a vast network of recruiters dangles the prospects of connections to well-heeled employers. While the Bangladeshi government could ramp up regulation and monitoring of recruitment agencies and their activities along the entire journey, this is a massive challenge, exacerbated by the intricate web of legal and illegal actors between origin and destination. In the meantime, workers will continue to pursue dangerous, uncertain paths—some making it to their destinations, while others find themselves detained or otherwise trapped in Libya, their Dubai Dreams deferred.

Sources

Afsar, Rita. 2000. Rural-Urban Migration in Bangladesh: Causes, Consequences, and Challenges. Dhaka: University Press Limited.

---. 2009. Unravelling the Vicious Cycle of Recruitment: Labour Migration from Bangladesh to the Gulf States. Geneva: International Labor Organization.

Ahmad, Reaz and Jamil Mahmud. 2017. Human Trafficking from Bangladesh: Kingpins Remain Unpunished. The Daily Star, July 30, 2017. Available online.

Amnesty International. 2017. Central Mediterranean: Death Toll Soars as EU Turns Its Back on Refugees and Migrants. News release, Amnesty International, July 6, 2017. Available online.

Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2016. Overseas Employment of Bangladeshi Workers: Trends, Prospects, and Challenges. ADB Briefs no. 63, Manila, August 2016. Available online.

Azad, Abid. 2016. Bangladeshi Asylum Seekers to Europe on the Rise. Dhaka Tribune, January 21, 2016. Available online.

Bal, Ellen. 2014. Yearning for Faraway Places: the Construction of Migration Desires among Young and Educated Bangladeshis in Dhaka. Identities 21 (3): 275-89.

Bangladesh Bureau for Manpower, Employment, and Training (BMET). N.d. Country-Wise Overseas Employment (from 1976 to 2017). Accessed September 18, 2017. Available online.

---. N.d. Overseas Employment in 2017 (Up to August). Accessed October 4, 2017. Available online.

---. N.d. Overseas Employment and Remittances from 1976-2017 (Up to August). Accessed October 4, 2017. Available online.

BBC News. 2017. Migrant Crisis: Italy Approves Libya Naval Mission. BBC News, August 2, 2017. Available online.

Blangiardo, Gian Carlo. 2009. Foreigner’s Presence in Italy: From a Reference Framework to Future Development Scenarios. In The Fifteenth Italian Report on Migrations, ed. Vincenzo Cesareo. Milan: Polimetrica.

Chugh, Nishtha. 2014. Bangladeshi Migrants Eke out a Living in Rome. Al Jazeera, November 6, 2014. Available online.

Cupolo, Diego. 2017. Explaining the Bangladeshi Migrant Surge into Italy. IRIN News, June 1, 2017. Available online.

Daily Star. 2017. Migrants in Europe: Dhaka to Seek More Time for Verification. The Daily Star, August 2, 2017. Available online.

Economist. 2016. The Other Kind of Immigration. The Economist, December 24, 2016. Available online.

Ejaz, Raheed. 2017. EU Threatens Visa Restrictions. Prothom Alo, July 30, 2017. Available online.

Husein, Naushad Ali. 2017. Escape to the Promised Land. Dhaka Tribune, August 3, 2017. Available online.

International Labor Organization (ILO) and International Institute for Labor Studies (IILS). 2013. Bangladesh: Seeking Better Employment Conditions for Better Socioeconomic Outcomes. Geneva: ILO and IILS. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals Reach 128,863 in 2017; Deaths Reach 2,550. Press release, September 15, 2017. Available online.

Lakshmi, Rama. 2016. Trump Calls for Mass Deportations. This Indian State is Already Weeding Out Undocumented Muslims. Washington Post, November 27, 2016. Available online.

Mannan, Kazi Abdul and Khandaker Mursheda Farhana. 2014. Legal Status, Remittances and Socio-economic Impacts on Rural Household in Bangladesh: An Empirical Study of Bangladeshi Migrants in Italy. International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research 3 (8): 52-72. Available online.

Middle East Monitor. 2016. Bangladeshi Workers Protest in Kuwait. Middle East Monitor, September 28, 2016. Available online.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI) Data Hub. N.d. Asylum Applications in the EU/EFTA by Country, 2008-2016. Accessed October 4, 2017. Available online.

---. N.d. Asylum Recognition Rates in the EU/EFTA by Country, 2008-2016. Accessed October 4, 2017. Available online.

Monzini, Paola. 2007. Sea-Border Crossings: The Organization of Irregular Migration to Italy. Mediterranean Politics 12 (2): 163-84.

Nur, Shah Alam. 2017. Bangladeshi Workers’ Deaths Abroad Up. Daily Asian Age, February 1, 2017. Available online.

Pastore, Ferruccio, Paola Monzini, and Giuseppe Sciortino. 2006. Schengen’s Soft Underbelly? Irregular Migration and Human Smuggling across Land and Sea Border to Italy. International Migration 44 (4): 95-119.

Rahman, Md Mizanur and Mohammad Alamgir Kabir. 2012. Moving to Europe: Bangladeshi Migration to Italy. Working paper no. 142, National University of Singapore Institute of South Asian Studies, February 6, 2012. Available online.

Reuters. 2017. Aid Groups Snub Italian Code of Conduct on Mediterranean Rescues. Reuters, July 31, 2017. Available online.

Tripathi, Sanjeev. 2016. Illegal Immigration from Bangladesh to India: Toward a Comprehensive Solution. Carnegie India, June 29, 2016. Available online.

UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2010. Smuggling of Migrants into, through and from North Africa. Vienna: UNODC. Available online.

---. 2016. Global Report on Trafficking in Persons. Vienna: UNODC. Available online.

Walsh, Declan and Jason Horowitz. 2017. Italy, Going It Alone, Stalls the Flow of Migrants. But at What Cost? New York Times, September 17, 2017. Available online.

World Bank Group and KNOMAD. Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. Migration and Development Brief 27, Washington, DC, April 2017. Available online.