You are here

Southeastern Europe Looks to Engage its Diaspora to Offset the Impact of Depopulation

The National Museum of History in Tirana, Albania features a large mosaic with nationalist imagery. (Photo: Dennis Jarvis)

Southeastern Europe is experiencing one of the sharpest depopulations in the world, led by Bulgaria, whose population is projected to drop nearly one-quarter by 2050. The most significant factor behind this trend is migration to Western Europe, which has remained widespread since the post-communist and post-conflict transition periods of the 1990s and 2000s. For example, half the total population in Bosnia and Herzegovina and 42 percent in Albania reside abroad, often in Western Europe.

In recent years, emigration has been compounded by low fertility and immigration rates, stalled social and human-rights advancements, and bleak economic projections, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. As several Southeastern European countries have joined the European Union and the Western Balkans begin to work toward accession, the region will continue to face sharp emigration in the years to come.

Aside from controversial proposals to restrict emigration and boost birth rates, countries are looking to their diaspora communities—defined as recent or permanent migrants and their descendants who identify with their countries of origin—as a key way to mitigate “brain drain” and depopulation. Over the past two decades, governments have gradually created diaspora-focused ministries and agencies and have begun working more with other actors, including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector, to deepen their engagement with citizens abroad and those who claim a shared ethnic heritage.

Diaspora engagement has traditionally focused on programs promoting cultural heritage, language acquisition, and the extension of political rights for those abroad who share a similar linguistic or ethnic heritage. It has since evolved to include economic programs, particularly for Southeastern European countries outside the European Union. This shift in focus is the result of continued emigration and the growing involvement in diaspora engagement of international organizations and private-sector firms seeking to prioritize economic development. Yet some governments nonetheless struggle to launch effective diaspora engagement projects that expand beyond cultural and language initiatives, due to a lack of strategic planning and little experience building institutions in this area.

This article examines the role of diaspora communities in contributing economically to their countries of origin in Southeastern Europe, particularly via remittances and business investment, as well as the differing strategies that countries have undertaken to strengthen bonds with their diasporas. It focuses on the EU Member States of Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, and Slovenia, and the Western Balkan states of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia.

Facing Demographic Decline

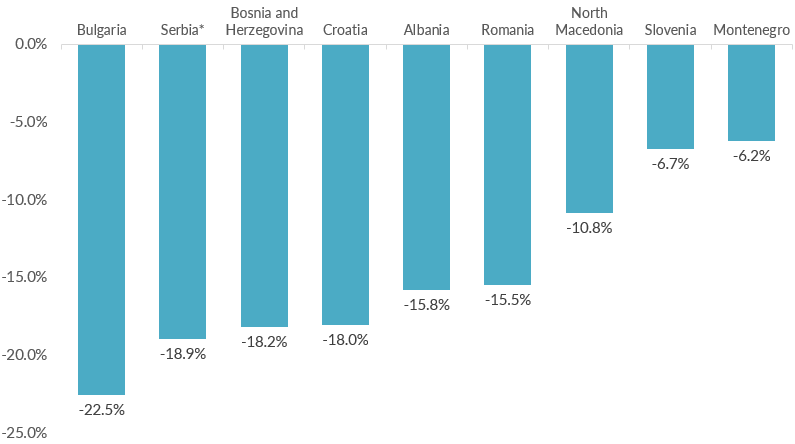

The demographic picture may be bleakest in Bulgaria, which is on course to face the world’s highest single-country depopulation rate over the next 30 years, according to the United Nations Population Division. Yet Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Albania, and Romania are not far behind, each expecting declines of 15 percent or more over the next three decades (see Figure 1). This phenomenon is occurring even as the world’s population is expected to increase by 2 billion people, to 9.7 billion in 2050.

Figure 1. Projected Population Change in Southeastern Europe, 2020-50

Note: United Nations data on Serbia include Kosovo’s population. The Kosovo Agency of Statistics projects a 6.6 percent decline between 2017 and 2050.

Sources: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), Population Division, “Probabilistic Population Projections Based on the World Population Prospects 2019,” accessed June 22, 2020, available online; Kosovo Agency of Statistics, Kosovo Population Projection 2017-2061 (Prishtina: Kosovo Agency of Statistics, 2017), available online.

Diasporas and Remittances in Southeastern Europe

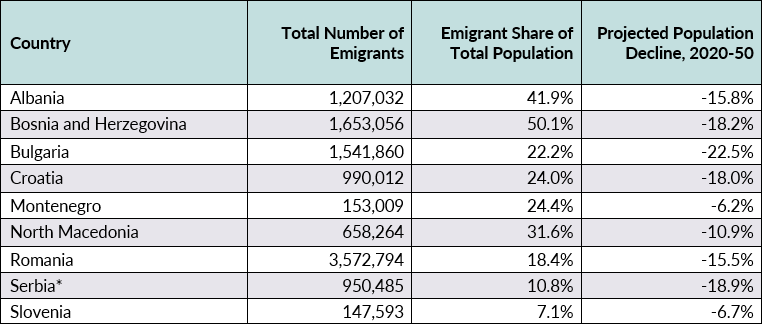

The region’s flow of emigrants represents a source of concern as it contributes to depopulation. Emigration has occurred unevenly across the region (see Table 1).

Table 1. Emigration from Southeastern Europe, 2019

Note: United Nations data on Serbia includes Kosovo’s population. The Kosovar government’s data on the estimated emigrant population is not reliable.

Sources: UN DESA Population Division, “UN Migrant Stock by Origin And Destination 2019,” accessed June 22, 2020, available online; UN DESA Population Division, “UN World Population Prospects 2019 Total Population for Both Sexes,” accessed June 22, 2020, available online.

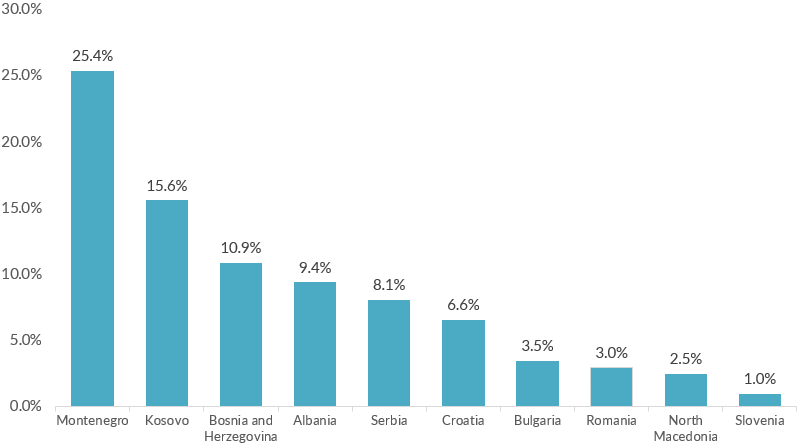

At the same time, however, these emigrants form the foundation for remittance inflows, which have provided a stable and predictable source of money to the region (see Figure 2). Remittances represent a significant financial lifeline for households and a large portion of the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of states in the pre-accession phase of joining the European Union. Romania received an estimated U.S. $7.2 billion in total official remittances in 2019, followed by Croatia and Serbia at just over U.S. $4 billion apiece.

Figure 2. Remittance Inflows as Share of GDP in Southeastern Europe, 2019

Source: World Bank, “Migration and Remittances Data: Annual Remittances Data,” updated as of April 2020, accessed June 25, 2020, available online.

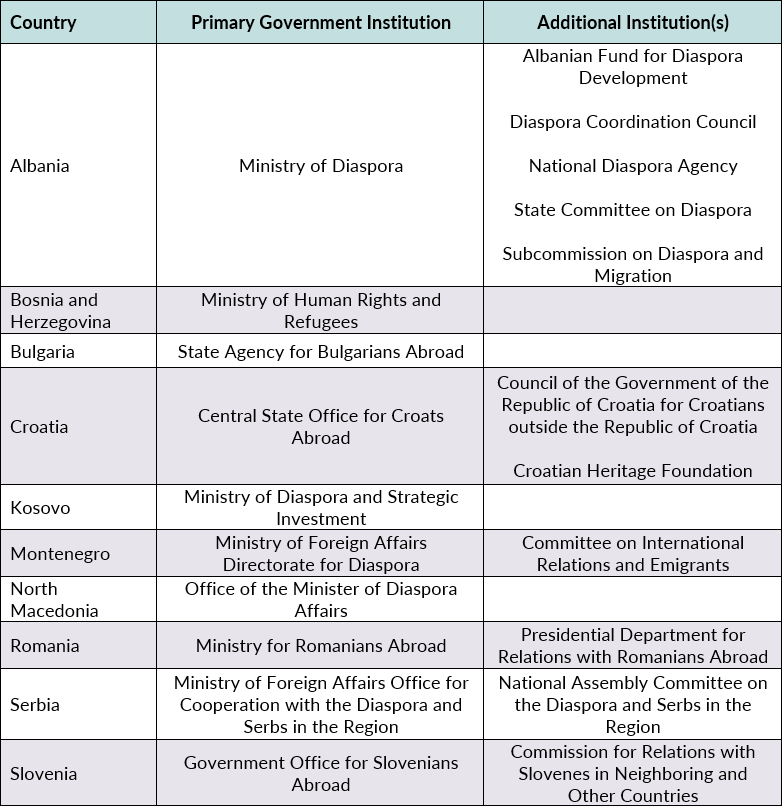

Governments Seek to Engage the Diaspora Intentionally

Governments in the region have actively worked to encourage their diasporas to remain connected via cultural and language programming, as well as to send remittances and other financial investments. Across government institutions, there is overlapping responsibility for diaspora engagement in consular services, programs within ministries of education, and economic development initiatives through ministries of finance, among others. Increasingly, however, central institutionalized bodies have been mandated to implement and govern engagement with diasporas at multiple levels. This is not unique to Southeastern Europe; worldwide, there were no fewer than 110 diaspora-targeted institutions as of mid-2020.

As part of this effort, governments have produced national plans for long-term diaspora engagement, as well as to map migrant communities abroad, offer assistance for returning migrants, and encourage financial transfers through innovative diaspora-targeted programs. The presumption underlying these initiatives is that beneficiaries in the diaspora will send back more remittances, foreign direct investment (FDI), and bonds, as well as share their social capital.

Differing Engagement

Due to their more diversified economies and other factors, the EU Member States of Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania focus less of their diaspora engagement attention on remittances, instead supporting cultural and language programs, especially for communities with shared ethnic heritage. Slovenia, another EU Member State, has experienced relatively low levels of emigration and has placed less of a priority on diaspora engagement, although the Office for Slovenians Abroad has focused on preserving cultural and language heritage as well as liaising with various diaspora associations.

While Bulgaria has the world’s highest rate of depopulation, it has yet to broaden its diaspora engagement to include financial and investment opportunities. Despite some achievements in mapping the diaspora, the State Agency for Bulgarians Abroad has predominantly focused on supporting cultural associations and providing administrative documentation to people of Bulgarian descent seeking Bulgarian citizenship. In 2018, the agency came under fire for its involvement in issuing fraudulent citizenship paperwork in exchange for bribes.

Croatia has tasked multiple ministries with responsibility for diaspora engagement, which have been most active in response to wartime policies of the 1990s and the subsequent return and reintegration of diaspora members and refugees. Croatia’s Central State Office for Croatians Abroad and the Croatian Heritage Foundation have maintained archival information on emigrants, provided scholarships to diaspora youth, and supported language and cultural heritage programs. The Croatian diaspora has regularly advocated for improved and easier measures for naturalization, external voting, and business networking.

Romania, which has the fifth-largest number of migrants in countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), has also remained slow in diversifying projects beyond the language and cultural domains. Since 2016, the government has provided financing to diaspora start-ups, but has been criticized by some private firms for not fostering larger financial and social capital programs or assisting returnees’ integration. Moreover, the ruling Social Democrat Party has been at odds with members of the diaspora, who have lobbied against ineffective external voting and organized anticorruption protests.

Priorities of Pre-Accession Countries

Meanwhile, government offices responsible for diaspora engagement in the pre-accession Western Balkan countries often have little institutional experience and have struggled to produce durable projects. Instead, countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and North Macedonia have worked with outside groups including international NGOs and transnational consulting firms to diversify their economic approaches and to better map their diasporas. Compared to their neighbors, these countries are in the early stages of developing diaspora engagement programs and predominantly target diasporas farther abroad, rather than in the region.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s institutional obstacles stem from the need to reach consensus among its ethnically divided communities, so it has turned to international organizations, civil-society groups, and private enterprises for assistance. The country has benefited from the support of external actors emphasizing localized engagement projects to mitigate the ethnic polarization typically found at the national level.

Over the last decade, Kosovo’s Ministry of Diaspora and Strategic Investment has carried out dozens of investment projects and conferences and facilitated international business networks to attract engagement from the Kosovar Albanian diaspora. Despite its proactive approach, however, the country has struggled with modernizing and making external voting more accessible. It also lacks adequate official data on its diaspora's background and has been slow to formulate a new national strategy.

Serbia has shuffled responsibility for diaspora engagement between several ministries for decades. The central office now governing diaspora relations has focused on providing assistance to and building capacity of Serbian associations, including business associations and media outlets. Yet many members of the diaspora have criticized the ruling Serbian Progressive Party’s push to normalize relations with Kosovo as well as President Aleksandar Vucic’s remarks in March 2020 blaming his country’s COVID-19 outbreak on returning migrants.

An exception to the trend is Albania, which has implemented diaspora engagement projects faster and more strategically than its neighbors. High emigration rates and large dependency on remittances and investment guided by members of the diaspora—often known as diaspora direct investment (DDI)—have prompted the Albanian government to enshrine diaspora engagement in key development strategies and task it to several institutional bodies. The Ministry of Diaspora has partnered with international organizations, the Albanian Investment Development Agency, and the private sector to implement projects and facilitate dialogue with the Albanian diaspora. Members of the diaspora have raised objections to the May 2020 demolition of Albania’s national theater, expressed concerns about the country’s rule of law, and bemoaned the lack of external voting rights.

Table 2. Governmental Diaspora Engagement Bodies in Southeastern Europe

Source: Author’s research.

Ethnic Nature of Diaspora Engagement

Diaspora engagement in Southeastern Europe reflects the region’s complicated post-conflict narratives and ethnically heterogeneous composition resulting from the dissolution of empires in the 19th and 20th centuries. Traditional diaspora engagement in the region has involved legislation supporting naturalization and granting external voting rights, as well as assistance for linguistic, religious, and cultural heritage programs for diasporas in neighboring states. Controversy surrounding these initiatives has faded somewhat, but there have been concerns among regional governments and geopolitical analysts that diaspora engagement projects promote irredentist movements and nationalistic interpretations of historical territories at odds with current borders. However, cultural bonding programs that regional states have long implemented are key in ensuring that both kin communities and emigrants maintain linkages with their countries of origin.

In many of these countries, states make clear distinctions between ethnic communities with a long connection to the homeland and those who migrated during earlier historical waves. A more recent secondary distinction, which developed during transitional periods of the 1990s and 2000s, has been drawn between “old” and “new” diasporas, depending on migration periods. For example, Croatia officially identifies three diaspora groups: Croats in neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croat minorities in other regional states such as Serbia, and Croatian migrants and their descendants who live farther away, such as in Ireland or Argentina.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the state’s power-sharing scheme between the three constituent ethnic groups—Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs—impedes diaspora engagement work. The Ministry of Human Rights and Refugees minimizes grievances by framing diaspora membership as a civic identity shared between the groups. The government framework therefore omits direct mention of projects aimed at communities claiming an ethnic heritage in neighboring states and instead focuses on recent migrants. In contrast, the national strategy developed by Romania’s Ministry of Romanians Abroad recognizes 10 million diaspora members, including self-identified Romanians and Romanian-speaking populations in neighboring states, including all Moldovans.

Diaspora engagement projects targeting newer and farther diasporas also reflect countries’ ethnic divisions. Most Southeast European diasporas benefit from services offered by their country of origin as well as by the country to which they have an ethnic tie, also known as their ethnic kinstate. In Serbian law, for example, diaspora benefits are extended to all ethnically Serbian persons abroad, not solely the direct descendants of people from the Republic of Serbia’s modern territory.

While it is up to individual diaspora members to choose which program or benefit best applies to them, competing diaspora engagement has placed pressures on states with less developed engagement projects. For example, international organizations operating in Bosnia and Herzegovina have faced challenges facilitating investments from the country’s Serbian or Croatian populations who are simultaneously incentivized to invest in their respective kinstates. In contrast, minorities with partial or indirect ties to a kinstate—such as Romani, Vlachs, Gorani, and Jews—are often ignored by Southeast European states’ diaspora engagement efforts.

Diaspora engagement projects in Albania and Kosovo provide a unique example where two ethnically overlapping states collaborate to share the positive outcomes of promoting and fostering Albanian heritage abroad. The governments have reached several diaspora engagement agreements, and the shared approach is outlined in their national strategies. Romania and Moldova have also signed agreements on cooperation in the domains of diaspora education, language, and diplomatic services, though their collaboration is less robust.

Growing Impact of Nongovernmental Actors

International organizations, private companies, and other nongovernmental actors have been working to support diaspora engagement and reduce bureaucratic barriers in governments in Southeastern Europe. They provide policy guidance, develop resources and processes for government bodies, and support the logistical implementation of diaspora-related projects. International organizations have had a particularly large operational role in pre-accession states.

International Organizations

International peacebuilding and development organizations in Southeastern Europe, particularly in the Western Balkan countries, have grappled with the ways in which emigration has and will continue to impact project beneficiaries, including youth and ethnic minorities. Diaspora engagement projects have been led by large organizations, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), and the UN Development Program (UNDP). These groups have implemented several projects to support diaspora mapping and encourage entrepreneurship and investment. ICMPD’s Link Up! project in Serbia, for example, has published assessments of the business needs and interests of Serbian diaspora members elsewhere in Europe. Similarly, IOM has worked to engage the Albanian diaspora to support diaspora-related policymaking and establish investment platforms for diaspora businesses.

Within the last decade, international actors have increasingly been involved in localized and decentralized projects in which they join with regional and municipal governments. This has been successful for several reasons: local investment opportunities avoid the bureaucracy and ethnic polarization endemic at the national level; these initiatives strengthen community connections with localities that diasporas trust; and, if channeled appropriately, investments and philanthropic activities advance development initiatives for underdeveloped regions. Working with local governments and diaspora members to funnel money into community projects is especially crucial in multiethnic regions where ethnic divides and distrust in central institutions can hinder the diaspora’s willingness to support national development.

One standing challenge for international organizations and diaspora engagement institutions is their heavy reliance on donor funding, which is often dependent on Western donors’ priorities and budget cycles. As a result, funding for these projects in the Western Balkans is not guaranteed and may be reallocated elsewhere. The region’s growing illiberalism, which often hinders human-rights principles promoted by international organizations, represents another challenge. International organizations working to mitigate depopulation through diaspora engagement or reproductive health can face pushback from governments promoting traditional gender roles, conservative family planning policies, and ethnonationalism.

Start-Ups and Investment Enterprises

Diaspora-led start-ups and established businesses have encouraged the inflow of remittances and investment, as well as the creation of networking connections. These companies mitigate bureaucratic challenges by offering technical, legal, and financial assistance to investors looking to do business in Southeastern Europe.

Restart, for example, has emerged as a leading consulting firm connecting the Bosnian diaspora and foreign investors to investment opportunities and talent pools in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Working within the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Diaspora Invest project, Restart has supported the establishment of businesses and employment opportunities. Similar services are offered by the Western Balkan Business Group, co-founded by members of the Bosnian diaspora, which provides assistance to Dutch companies working in the Western Balkans. EU Member States are not immune to the trend. In Romania, the SMART Development Center provides financial, technical, and training assistance to diaspora start-ups in targeted areas. These companies claim to positively represent the region’s markets abroad and showcase the benefits of diasporas to domestic audiences.

Enterprises in other countries across the region tap into diaspora populations to provide financial, technical, and marketing assistance for Southeastern European markets. They emphasize creating economic and investment connections rather than cultural or political bonds.

COVID-19 Disrupts Transfers but Underscores Diasporas’ Role

The coronavirus pandemic has upended diaspora engagement, as it has disrupted migration networks across the globe. Since March 2020, international remittance transfers to Southeast Europe have been significantly disrupted. The World Bank predicted in April that Europe and Central Asia would face a 27.5 percent decline in remittances in 2020, the largest of any region.

Additional challenges are likely for states with large tourism industries, such as Albania, Croatia, Kosovo, and Montenegro. The World Bank predicted that Albania, Kosovo, and Montenegro could lose up to half of their expected tourism revenue if travel restrictions remain in place through August. While many countries have begun reopening borders, ongoing international travel restrictions and the possibility of future border closures will undoubtedly continue to impact economic stability.

At the same time, the pandemic has also exposed Western Europe’s reliance on Eastern European migrants. Seasonal workers have continued to travel to Western Europe from Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania to satisfy its demand for cheap labor. Germany’s agriculture and interior ministries, for example, lifted labor restrictions for seasonal workers from Romania at the beginning of April, and by May the German government allowed chartered flights to bring in thousands of Romanians. Yet some migrants may find that high unemployment and a lack of social assistance will force them back to their countries of origin. These returnees are likely to remain vulnerable to precarious labor contracts, as well as the cycle of out-migration due to a lack of employment opportunities in their countries of origin and few integration mechanisms for returnees.

Regional Lessons and Opportunities

The European Commission is among those that have identified brain drain as a significant issue affecting Southeastern Europe. Within the European Commission’s enlargement strategy for the Western Balkans, it earmarked economic development and job creation as potential tactics to curb emigration. Once new Member States are admitted, the accession rules undoubtedly will include provisions temporarily limiting and regulating access to the EU labor market in order to mitigate immediate large-scale migration. Nonetheless, as transitional systems in Bulgaria Croatia, and Romania have shown, many individuals will likely make use of their new right to freedom of movement.

There is no European Union-wide strategy to curb East-West migration or improve regional diaspora engagement to mitigate the impact of depopulation. However, the growing importance and successes of diaspora engagement strategies across Southeastern Europe provide a vital testing ground for plausible policy prescriptions.

Southeastern European governments have begun shifting their diaspora engagement to include economic engagement, yet the region—particularly EU Member States that receive less guidance from international organizations—continues to face logistical and capacity challenges. Governments lack important data about their diasporas and face challenges from emigrants and their children who feel less connections to the countries of origin, as well as from returnees who require specialized support.

While diaspora engagement alone cannot address the broader demographic challenges that Southeast European states experience, it can help mitigate some of the social and economic losses. Diaspora engagement requires long-term planning, and policymakers should not assume diasporas will automatically contribute to their states of origin. By fostering positive, mutually beneficial relations and implementing investment-friendly policies, Southeastern European states can continue to enable capital transfers to support regional development amid the challenges of large-scale depopulation.

Sources

Armitage, Alanna. 2019. What to Do about Eastern Europe’s Population Crisis? News release, United Nations Population Fund, October 22, 2019. Available online.

Andriescu, Monica. 2020. Under Lockdown Amid COVID-19 Pandemic, Europe Feels the Pinch from Slowed Intra-EU Labor Mobility. Migration Information Source, May 1, 2020. Available online.

Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN). 2020. Balkan Countries Relax Guard Despite COVID-19’s Second Wave. Balkan Insight, June 18, 2020. Available online.

Bami, Xhorxhina. 2019. Kosovo Failing to Protect Diaspora Rights and Tap Potential. Balkan Insight, November 1, 2019. Available online.

Brubaker, William Rogers. 2015. Nationalizing States and Ethno-national Boundaries: A Comparative Perspective on Soviet Successor States. In Nationalism, Ethnicity and Boundaries: Conceptualising and Understanding Identity through Boundary Approaches, eds. Jennifer Jackson and Lina Molokotos-Liederman. New York: Routledge.

Chudinovskikh, Olga and Mikhail Denisenko. 2017. Russia: A Migration System with Soviet Roots. Migration Information Source, May 18, 2017. Available online.

Gamlen, Alan, Michael E. Cummings, and Paul M. Vaaler. 2017. Explaining the Rise of Diaspora Institutions. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (4): 492-516.

Garding, Sarah. 2018. Weak by Design? Diaspora Engagement and Institutional Change in Croatia and Serbia. International Political Science Review 39 (3): 353-68.

Gazsó, Dániel. 2017. Diaspora Policies in Theory and Practice. Hungarian Journal of Minority Studies 1 (1): 65-87. Available online.

Judah, Tim. 2019. Kosovo’s Demographic Destiny Looks Eerily Familiar. Balkan Insight, November 7, 2019. Available online.

Kiersz, Andy and Madison Hoff. 2020. The 20 Fastest-Shrinking Countries in the World. Business Insider, July 16, 2020. Available online.

Koch, Svetlana. 2020. The Formation of Bulgaria's Policy Concerning Bulgarians Abroad. International Centre for Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity Studies, January 27, 2020. Available online.

Koinova, Maria and Gerasimos Tsourapas. 2018. How Do Countries of Origin Engage Migrants and Diasporas? Multiple Actors and Comparative Perspectives. International Political Science Review 39 (3): 311-21. Available online.

Kosovo Agency of Statistics. 2017. Kosovo Population Projection 2017-2061. Prishtina: Kosovo Agency of Statistics. Available online.

Krasteva, Anna, Amir Haxhikadrija, Dragana Marjanovic, Miriam Neziri Angoni, Marjan Petreski, et al. 2018. Maximising the Development Impact of Labour Migration in the Western Balkans. Brussels: IBF International Consulting. Available online.

Kurečić, Petar, Marin Milković, and Igor Klopotan. 2019. A European Perspective of the Western Balkans: Drawing on the Experiences of Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. Paper presented at the 38th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Rabat. Available online.

McIntyre, Chris and Alan Gamlen. 2019. States of Belonging: How Conceptions of National Membership Guide State Diaspora Engagement. Geoforum 103: 36-46. Available online.

Ministry of Human Rights and Refugees of Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2017. Policy on Cooperation with Diaspora. Official Gazette of Bosnia and Herzegovina no. 38/17. Available online.

Ministry of Romanians Abroad. 2017. National Strategy for Romanians Abroad 2017 – 2020. Available online.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2019. Talent Abroad: A Review of Romanian Emigrants. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online.

Republic of Albania, Ministry of State on Diaspora. 2018. National Strategy on Diaspora and Migration 2018-2024. Available online.

Republic of Bulgaria. 2014. National Strategy for Bulgarian Citizens and Historical Communities Around the World. Available online.

Republic of Croatia. 2011. Act on the Relations between the Republic of Croatia and the Croatians Outside the Republic of Croatia. Zagreb: The Croatian Parliament. Available online.

Republic of Kosovo Ministry of Diaspora and Strategic Investment. 2013. National Strategy for Diaspora 2019-2023. Available online.

Republic of Montenegro. 2018. Law on Cooperation between Montenegro and the Diaspora-Emigrants. Available online.

Republic of North Macedonia. 2019. National Strategy for Cooperation with the Diaspora 2019-2023. Available online.

Republic of Serbia. 2009. Law on Diaspora and Serbs in the Region. Republic of Serbia Official Gazette No. 88/09. Available online.

---. 2011. National Strategy of Preserving and Strengthening Relations between the Mother Country and Diaspora and Serbs of the Region. Available online.

Republic of Slovenia. 2008. Strategy for Relations Between the Republic of Slovenia and Slovenians Abroad. Available online.

Riazantsev, Sergei. 2016. The New Concept of Migration Policy of the Russian Federation. In The EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood: Migration, Borders and Regional Stability, eds. Ilkka Liikanen, James W. Scott, and Tiina Sotkasiira. New York: Routledge.

Sandu, Dumitru, Georgiana Toth, and Elena Tudor. 2018. The Nexus of Motivation–Experience in the Migration Process of Young Romanians. Population, Space and Place 24 (1), e2114. Available online.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. Probabilistic Population Projections Based on the World Population Prospects 2019. Accessed June 22, 2020. Available online.

---. 2019. World Population Prospects 2019. New York: United Nations. Available online.

Vracic, Alida. 2018. The Way Back: Brain Drain and Prosperity in the Western Balkans. London: European Council on Foreign Relations. Available online.

Waterbury, Myra A. 2018. Caught between Nationalism and Transnationalism: How Central and East European States Respond to East–West Emigration. International Political Science Review 39 (3): 338-52. Available online.

Weisskircher, Manès, Julia Rone, and Mariana S. Mendes. 2020. The Only Frequent Flyers Left: Migrant Workers in the EU in Times of COVID-19. Open Democracy, April 20, 2020. Available online.

World Bank Group. 2020. Migration and Remittances Data: Annual Remittances Data (Updated as of April 2020). Accessed June 25, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Western Balkans Regular Economic Report No.17: The Economic and Social Impact of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online.

---. 2020. World Bank Predicts Sharpest Decline of Remittances in Recent History. Press release, April 22, 2020. Available online.