You are here

Can the Biden Immigration Playbook Be Effective for Managing Arrivals via Sea?

The U.S. Coast Guard interdicts a vessel with Cuban migrants. (Photo: Cutter Hamilton crew/U.S. Coast Guard)

The Biden administration’s immigration playbook has become increasingly clear. Amid record arrivals of asylum seekers and other migrants coming without prior authorization to enter the United States, it is limiting access to protections for people arriving between ports of entry, opening alternative legal pathways for people fleeing difficult situations, and working with other countries to manage flows before migrants reach U.S. soil. This is, broadly speaking, the strategy the administration is employing to counter record pressures at the U.S.-Mexico border. And it is also the approach for contending with the increasing numbers of migrants traveling on small boats through the Caribbean to reach U.S. shores.

In This Article:

Rising maritime migration has been overshadowed by events at the U.S.-Mexico border, but is presenting a formidable challenge of its own to the U.S. government, one unseen in decades. Cubans and Haitians in particular have been taking to the sea in numbers not witnessed in a generation, and the Haitian numbers could surge as that country spirals closer to collapse. As a result, the United States is faced with a challenge that has more recently bedeviled governments in Australia and Europe: how to spot and halt small and typically unseaworthy boats to prevent loss of life, and beyond that, how to prevent individuals from setting off in the first place.

As with asylum seekers and other migrants arriving by land, the administration is seeking to disincentivize unauthorized maritime arrivals by expanding legal pathways and making ineligible for asylum those who do not present at a port of entry with an appointment. It has also embraced a regional approach, building on agreements with The Bahamas and Turks and Caicos to expand the ability of all three countries’ authorities to interdict migrants closer to their setting-off points and return them. Other migrant-receiving countries, which have a history of using offshore detention centers and migration enforcement in transit nations to deter irregular arrivals, are watching this increased regional cooperation with interest.

Early indications suggest the new policies are resulting in a greater number of arrivals occurring through legal channels. Although overall interdictions at sea are just a tiny fraction of the number of arrivals to the U.S.-Mexico border, maritime migration is a critical element in the Western Hemisphere’s migration patterns and a much larger phenomenon globally. This article examines recent maritime trends, policy responses, and challenges ahead.

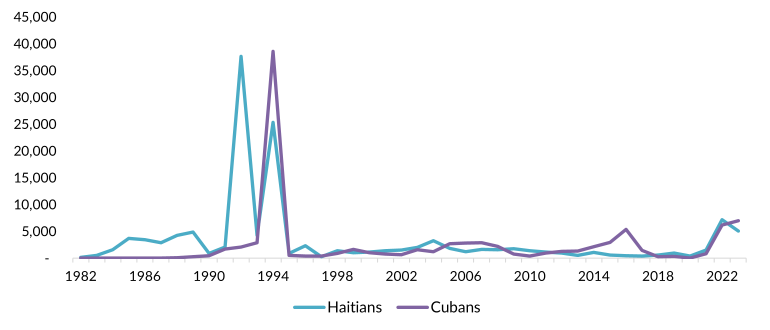

Recent maritime flows of Cubans and Haitians to the United States have reached the highest levels since the 1990s: 7,000 Haitians and 6,000 Cubans were interdicted at sea by U.S. officials in fiscal year (FY) 2022, and initial data show similar numbers in FY 2023. Notably, it is not just Cubans and Haitians traveling through Caribbean waters; the U.S. Coast Guard interdicted nearly 2,000 migrants from the Dominican Republic in FY 2023, as well as smaller numbers from Kazakhstan, Venezuela, and other countries. Last year was also the deadliest for Caribbean migration in recent history, with 321 deaths and disappearances, up from 180 in 2021. This number likely represents a fraction of the deaths that are never identified.

Figure 1. U.S. Coast Guard Interdictions of Cuban and Haitian Migrants, FY 1982-2023*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 are for the first 11 months of the year.

Sources: Muzaffar Chishti and Jessica Bolter, “Rise in Maritime Migration to the United States Is a Reminder of Chapters Past,” Migration Information Source, May 25, 2022, available online; Kathleen Newland, Elizabeth Collett, Kate Hooper, and Sarah Flamm, All at Sea: The Policy Challenges of Rescue, Interception, and Long-Term Response to Maritime Migration (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2016), available online; U.S. Coast Guard News, “Coast Guard Repatriates 27 People to Cuba” (press release, August 5, 2023), available online; U.S. Coast Guard News, “Coast Guard Transfers 275 Migrants to Bahamas” (press release, July 17, 2023) available online.

The U.S. Coast Guard estimated its interdiction success rate was 56.6 percent in FY 2022, meaning thousands of people likely reached U.S. shores without being intercepted. In January, a national park in the Florida Keys closed due to the arrival of 300 migrants by boat, and the Miami sector of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which covers more than 1,200 miles of Florida’s coast, reported nearly 6,000 encounters in FY 2023, up from 4,000 the previous year. Many others may have evaded detection altogether. Wealthier migrants, for instance, have reportedly sailed into Miami Beach looking like local tourists.

Perhaps partly in response to these new levels of interdictions, the Biden administration included maritime migrants in its 2023 policy to disqualify from asylum those who travel to the United States without authorization. The change was a little-recognized component of the reforms unveiled as the pandemic-era Title 42 expulsions policy came to an end in May.

International cooperation today relies on agreements with transit countries to help interdict boats and with migrants’ origin countries to make migration better managed and safer. This regional cooperation ensures that responsibility for migration management does not fall on the United States alone, and meanwhile allows the U.S. government to have a broader scope of operations within the region. The trend towards multilateral regional cooperation, rather than bilateral agreements, mirrors other U.S. efforts in the Western Hemisphere to manage land-based migration, including the 2022 Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection, an agreement with leaders of 21 countries across the Americas, a number of whom will meet with President Joe Biden to discuss regional migration challenges at a November summit.

The Bahamas and Turks and Caicos are key U.S. partners for enforcement in the Caribbean. These territories are comprised of hundreds of islands over a vast territory adjacent to U.S. waters. As part of the partnership, these countries provide real-time operational intelligence to the U.S. Coast Guard. Since 1982, the United States, The Bahamas, and Turks and Caicos have been in a trilateral agreement called Operation Bahamas, Turks and Caicos (OPBAT). Initially focused on narcotics interdiction, the operation in 2004 grew to incorporate coordination on interdicting migrants at sea.

OPBAT allows the Coast Guard, the Royal Bahamas Police Force (RBPF), and the Royal Turks and Caicos Police Force (RTCPF) to enter each other’s territorial waters to enable coordination and information sharing. These agencies share navigational software and work together on search and rescue, migrant interdictions, and anti-smuggling operations. The U.S. Coast Guard also offers training and resources such as ships to the RBPF and RTCPF. Because of this cooperation, many interdictions occur in Bahamian waters, and migrants are transferred to Bahamian authorities for repatriation to their country of origin.

This year, the United States also hosted the first-ever Northern Caribbean Security Summit, involving officials from those two countries and the United Kingdom, focused on enhancing partnerships in the Caribbean. In September, the U.S. government held a symposium on human trafficking at the U.S. embassy in Nassau.

These types of engagements point to renewed and ongoing efforts to build upon longstanding regional agreements, with Caribbean migration assuming a larger role due to changing patterns. Earlier agreements have taken on new importance as maritime migration shows no signs of slowing.

Cooperation with Countries of Origin

U.S. cooperation with countries of high emigration tends to depend on government relationships, which can be complicated. The Biden administration has tried to revive a warmer relationship with Cuba that was initiated during the Obama era but then put on ice by the Trump administration. As a result, the U.S. government has restarted a family reunification parole program for Cubans (discussed below) and authorized in-country processing for protection claims, making it easier for Cubans to migrate to the United States through legal channels.

In-country processing is impractical in Haiti, given the absence of a functioning government and political crisis since the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse. However, the U.S. Coast Guard is preparing for a possible new surge in emigration from Haiti through Operation Vigilant Sentry, an operational framework first approved in 2004 that combines air and marine responses to react to events of mass migration in the Caribbean.

The Promise of Legal Pathways?

The Biden administration has also introduced lawful immigration pathways to reduce unauthorized arrivals of Cubans and Haitians, as well as Nicaraguans and Venezuelans. A program that grants humanitarian parole to up to 30,000 migrants per month from these four countries was created in response to record arrivals of these nationalities at the southwest border and the government’s inability to return them due to limited repatriation agreements with their origin governments. The parole program, which also allows the United States to expel to Mexico up to 30,000 migrants monthly crossing the border without authorization, may have had an impact on maritime arrivals by incentivizing migrants to apply for permission to travel to the United States.

Last year the administration also restarted family reunification programs for Cubans and Haitians that were first launched in 2007 and 2014 respectively; they were halted during the Trump administration. High arrivals of those nationalities have occurred recently in the Miami sector of CBP’s Office of Field Operations (OFO), which manages ports of entry including the Miami airport where migrants can enter through these programs, suggesting the pathways have offered a legal alternative to irregular arrivals for some migrants.

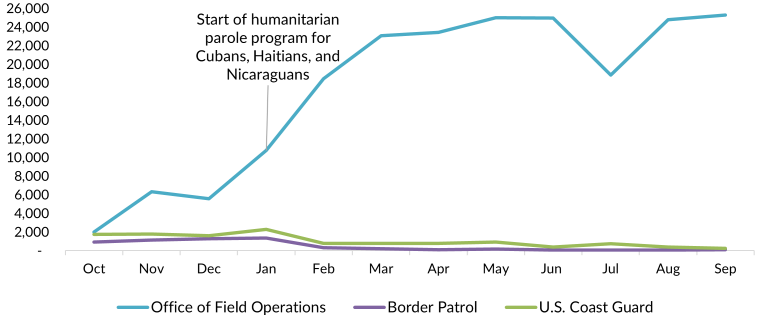

In FY 2023, Miami has been OFO’s busiest sector aside from those on the southwest border. The steady increase in arrivals correlates with the implementation of the parole program for Venezuelans in October 2022, and its extension to Cubans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans in January. More than 42,000 Cubans and nearly 68,000 Haitians arrived via the Miami OFO in FY 2023, a sharp rise over the 346 and 130 respectively in FY 2022.

Irregular encounters on land are the responsibility of the Border Patrol. Its Miami sector has seen lower numbers than the Miami OFO or sectors on the southwest border, though numbers had increased all the same. In FY 2021, migrants were encountered just over 1,000 times in the Border Patrol’s Miami sector, jumping to 4,000 in FY 2022 and more than 5,700 in FY 2023. However, encounters in the Border Patrol’s Miami sector dropped from nearly 1,400 in January to 300 in February following the implementation of the parole processes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Migrant Encounters in U.S. Border Patrol and Office of Field Operations’ Miami Sectors and U.S. Coast Guard Migrant Interdictions, FY 2023

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulations based on data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “Nationwide Encounters,” updated October 22, 2023, available online; U.S. Coast Guard, “Maritime Law Enforcement Data,” accessed October 24, 2023, available online.

Evolution of Interdiction Agreements: Limited Access to Humanitarian Protections

U.S. interdictions of migrants arriving on small boats began in force in the 1980s and was bolstered by a 1981 agreement between Haitian President Jean-Claude Duvalier and U.S. President Ronald Reagan. Agreements such as this were the forerunner of today’s multilateral pacts, which typically do not provide interdicted migrants access to asylum in the United States. Rather, individuals are sent back to their country of origin or, if interdicted by U.S. authorities, sometimes transferred to the Migrant Operations Center at the U.S. Naval Station in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and screened for possible resettlement in a third country.

Regional pacts such as OPBAT allow authorities to carry out interdictions in other countries’ waters, so migrants can be returned as close as possible to where they are encountered. If held by the U.S. Coast Guard, interdicted migrants are typically kept on deck, separated by gender. Coast Guard personnel visually assess maritime arrivals for protection needs. For example, if migrants appear to be in distress or assert they fear return to their home country, they will be screened for humanitarian protection. As with migrants encountered on land, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officers conduct interviews (by phone or in person) to determine whether migrants have a credible fear of persecution or torture in their origin country; if so, they may be processed for resettlement in a third country. The rest are summarily returned.

For more than 30 years, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the State Department have used the Migrant Operations Center at Guantanamo to process individuals interdicted at sea. In anticipation of a possible new mass exodus of Haitians, the Biden administration in 2022 reportedly considered doubling the migrant holding capacity at Guantanamo to 400 beds. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is responsible for caring for migrants awaiting USCIS screenings as well as those found ineligible for protection who are awaiting repatriation. The State Department is responsible for the care of migrants eligible for refugee resettlement abroad.

Only about 1 percent of people interdicted are found eligible for protection, according to the U.S. Coast Guard, though immigrant-rights advocates have long claimed the lack of systematic screening and access to asylum violate international law. In January, the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties opened an investigation into interdiction practices, protection screening, and migrant care, after almost 300 nonprofit organizations alleged that U.S. operations discriminated against migrants traveling at sea and create a dangerous precedent for other countries.

Other Countries’ Practices

Indeed, other countries are keenly watching U.S. policy developments at its borders and at sea. Many leaders worldwide are facing pressure to curb irregular arrivals and may be looking to the United States for lessons. For instance, some critics of Australia’s restrictive maritime migration policy have suggested that longstanding U.S. practices with regard to maritime interdictions offered Canberra a license to limit access to its territory. Relying on migration enforcement agreements with countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia, Australia has also transferred migrants to the country of Nauru and Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island for detention, processing, and possible resettlement. Even after emptying the Nauru facility this year, Canberra still committed to paying hundreds of millions of dollars to maintain facilities there as a contingency for future boat arrivals.

The European Union and its Member States have inked extensive migration management agreements with Turkey and countries in North Africa. EU officials generally do not screen migrants for protection claims onboard vessels, so the United States’ practice of doing so is of interest, though arrivals to the bloc vastly outstrip those coming by the Caribbean. As of late October, about 209,000 migrants arrived by sea in Southern Europe, more than any year since 2016. These numbers have complicated efforts for EU Member States to sign a new migration and asylum agreement that involves burden-sharing and the distribution of migrants across the bloc. The perilous journeys across the Mediterranean, epitomized recently by the arrival of about 12,000 migrants to the small Italian island of Lampedusa over a few days in September, has helped advance the narrative of populists across Europe.

Ultimately, differences in countries’ legal frameworks and political contexts limit how much they can directly borrow from each other. Unlike in the United States, the European Court of Human Rights has found that EU Member States are bound by principles of international law at sea, limiting their ability to summarily return migrants. Since leaving the European Union and its common policies on asylum in 2020, the United Kingdom has sought to send asylum seekers crossing the English Channel to Rwanda, but courts have so far held up the policy. Despite decades of infusions of billions of dollars for increased migration enforcement on land, the U.S. government has been less willing to significantly increase spending on maritime interdiction. For example, the total U.S. Coast Guard budget went from $11 billion in FY 2013 to $13.9 billion in FY 2023, meanwhile the CBP’s budget increased from $11.7 billion in FY 2013 to $20.9 billion in FY 2023, and ICE’s increased from $5.6 billion in FY 2013 to $9.1 billion in FY 2023. In the latest supplemental funding request for border security, there was no mention of additional funding for the Coast Guard.

What’s Old Is New Again?

Irregular migration across the Caribbean was a serious issue for the United States in previous decades and is re-emerging. As maritime migration has increased, the trend has put Washington in a more robust conversation with its own policy history.

In this new chapter, the United States is facing twin challenges of asylum seekers and other migrants arriving via its land borders and on the high seas. This is a reflection of growing humanitarian pressures globally and significant push factors, including ongoing economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic and political unrest. While early indications suggest U.S. policies may encourage some migrants to take lawful routes rather than unsafe maritime journeys, the increasing diversity of nationalities attempting to reach the United States by sea may soon present a similar challenge as it does at the land border. The Biden administration’s analogous responses on both fronts suggest it firmly believes in its strategy of regional cooperation, new legal avenues, and burden-sharing that provides protection only to those eligible. In its view, this combination addresses both the humanitarian challenges and the political vulnerability that increased migration presents.

The authors thank Faith Williams for her research assistance.

Sources

Ahn, Ashley. 2023. An Influx of 300 Migrants Forces Closure of a National Park in the Florida Keys. National Public Radio, January 3, 2023. Available online.

Alvarez, Priscilla. 2022. More Cubans Are Coming to the US by Sea than Any Time Since the 1990s. CNN, September 23, 2022. Available online.

Bowman, Emma. 2023. More than 2,500 Migrants Crossing the Mediterranean Died or Went Missing This Year. National Public Radio, September 29, 2023. Available online.

Brennan, Margaret and Ed O'Keefe. 2023. Biden to Host First-of-Its-Kind Americas Summit to Address Immigration Struggles. CBS News, October 20, 2023. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Jessica Bolter. 2022. Rise in Maritime Migration to the United States Is a Reminder of Chapters Past. Migration Information Source, May 25, 2022. Available online.

Feltovic, Michael and Robert O’Donnell. 2023. Coast Guard Migrant Interdiction Operations Are in a State of Emergency. Proceedings 149 (2): 1440. Available online.

Hacock, Sam and Sam Francis. 2023. Illegal Migration Bill: Government Sees Off Final Lords Challenge. BBC News, July 18, 2023. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2023. Missing Migrants in the Caribbean Reached a Record High in 2022. Press release, January 24, 2023. Available online.

José Espinosa, María, Mariakarla Nodarse Venancio, and Natalie Omodt. 2022. U.S.-Cuba Relations: The Old, the New, and What Should Come Next. Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) commentary, Washington, DC, December 16, 2022. Available online.

Karp, Paul and Tory Shepherd. 2023. Nauru Offshore Processing to Cost Australian Taxpayers $485m Despite Only 22 Asylum Seekers Remaining. The Guardian, May 22, 2023. Available online.

Kerwin, Donald and Evin Millet. 2023. The US Immigration Courts, Dumping Ground for the Nation’s Systemic Immigration Failures: The Causes, Composition, and Politically Difficult Solutions to the Court Backlog. Journal on Migration and Human Security 11 (2): 23315024231175379. Available online.

Newland, Kathleen, Elizabeth Collett, Kate Hooper, and Sarah Flamm. 2016. All at Sea: The Policy Challenges of Rescue, Interception, and Long-Term Response to Maritime Migration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Schmidt, Samantha, Paulina Villegas, and Hannah Dormido. 2023. Dreams and Deadly Seas. The Washington Post, July 27, 2023. Available online.

Shachar, Ayelet. 2022. Instruments of Evasion: The Global Dispersion of Rights-Restricting Migration Policies. California Law Review 110: 967-1009. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. Mediterranean Situation. Updated October 22, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. Refugee Crisis in Europe: Aid, Statistics, and News. Accessed October 18, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). N.d. Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans. Accessed October 18, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Coast Guard Aviation History. N.d. 1982 – OPBAT – Operation Bahamas Turks and Caicos; a Cooperative Drug Interdiction Operation Initiated. Accessed October 18, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Coast Guard News. Coast Guard Repatriates 27 People to Cuba. Press release, August 5, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Coast Guard Returns 189 Migrants to the Dominican Republic, Following 5 Migrant Vessel Interdictions in the Mona Passage. May 9, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Coast Guard Transfers 275 Migrants to Bahamas. Press release, July 17, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Operation Vigilant Sentry: Stopping Illegal Migration at Sea. Press release, January 27, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. U.S. Government Hosts Inaugural Northern Caribbean Security Summit. Press release, March 16, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2023. Nationwide Encounters. Updated September 22, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). U.S. Coast Guard Fiscal Year 2014 Congressional Justification. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

---. 2023. U.S. Coast Guard Budget Overview: Fiscal Year 2024 Congressional Justification. Washington DC: DHS. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. 2023. Maritime Interdiction, Protection Screening, and Custody of Migrants in the Caribbean Complaint No. 005118-23-DHS. Memorandum, DHS, Washington, DC, January 20, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Embassy Nassau. 2020. U.S. and Bahamas Sign Updated Search and Rescue Agreement, December 11, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. Coast Guard Liaison Office. Accessed October 18, 2023. Available online.

U.S. State Department. 2004. Narcotic Drugs: Maritime Cooperation, Agreement between the United States of America and the Bahamas. June 29, 2004. Available online.

---. 2022. Defense: Status of Forces Agreement, Agreement between the United States of America and the Bahamas. April 19, 2022. Available online.

U.S. State Department, Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. 2023. U.S. Relations with the Bahamas: Bilateral Relations. Fact sheet, State Department, Washington, DC, July 10, 2023. Available online.