You are here

New York and Other U.S. Cities Struggle with High Costs of Migrant Arrivals

New York City Mayor Eric Adams meeting with asylum seekers. (Photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The likely record number of asylum seekers and other migrants entering the United States after being apprehended at the southern border is placing an unprecedented financial strain on states and cities nationwide, even as local governments continue to recover from the economic toll resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The absence of federal support to significantly defray state and local costs, long waits for migrants to work legally, and large numbers arriving without connections in the country have combined to create an inordinate burden for several major receiving cities, which have spent billions to meet immediate needs. The situation has aggravated already tight housing markets and prompted a blame game pitting city, state, and federal leaders against each other.

New York City Mayor Eric Adams has been most vocal about his frustration with the federal government, sparking tensions with the White House with recent remarks that a migrant influx he estimates will cost New Yorkers $12 billion by mid-2025 “will destroy” the city.

While cities have historically absorbed and integrated new migrants with success, the challenges brought by the new border arrivals are due not only to the high numbers but also the diversity of nationalities, the large share arriving as families, and the overwhelming number who seek asylum. New arrivals are entitled to almost no federal public benefits and those lacking a family or social connection in the United States are having difficulty finding a foothold in U.S. communities. Unlike in the past, when migrants arriving without authorization tended to avoid federal authorities, new border entrants have already been processed by the government, so may be more likely to ask for government assistance.

The challenge is most severe in New York City, which has a unique legal obligation to provide shelter to anyone who needs it. The city has struggled to house migrants while also handling the regular challenges of unhoused New Yorkers, and has turned to hotels, a cruise ship terminal, a former police academy building, and other locations. New York and other cities are also bearing the burden of paying for medical care, schooling, food, and other services.

Although the full fiscal impacts of providing services to the newcomers are unknown, mayors and governors nationwide have cited high costs. New York City spent an estimated $1.7 billion on shelter, food, and other services for migrants through the end of July. Chicago expects to have spent $255.7 million between August 2022 and the end of 2023. Washington, DC spent $36.4 million on migrant services by late August, and expects the total to reach $55.8 million by October. Denver, where leaders estimate that every new arrival costs an average of between $1,600 to $2,000, has spent $24 million on migrant services as of September. And the impacts are not just on city budgets. Massachusetts’s governor said the state was spending $45 million a month on migrant services as of August. Strained resources have prompted mayors and governors, many of them Democrats, to join a chorus of criticism directed at the Biden administration for its handling of increased migrant arrivals.

In recognition of the strains on public coffers and political relationships, the administration last week offered Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to as many as 472,000 Venezuelans who arrived in the United States on or before July 31, which would provide them 18 months of protection from deportation and work authorization. This designation supplemented a prior TPS offer to Venezuelans and greatly expands the total number of TPS-eligible people of various nationalities, to nearly 1.7 million. But given current processing challenges at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), it may still take several months for eligible Venezuelans to receive their work permits and formally enter labor markets.

USCIS also announced last week that it is planning to accelerate the processing of work authorization applications for migrants granted humanitarian parole, another type of status that does not lead to permanent residence but confers temporary right to stay in the United States and eligibility for work authorization. USCIS intends to complete work permit applications within a median 30 days (down from the current 90) and make many work authorizations valid for five years (up from two years) for asylum applicants and recipients, refugees, and certain other groups.

The TPS change in particular, and the fact that it allows beneficiaries to work legally, had been a major priority of New York leaders and could benefit an estimated 60,000 Venezuelans in the city. Immigrant-rights advocates also had been pressing the administration for the designation.

This article explores how new arrivals are relying on local services for extended periods of time due to their lack of social networks and limited access to public benefits, and how inadequate federal aid has caused local governments to incur new unplanned costs. It outlines the services cities have put in place and the challenges of meeting the needs of newly arrived migrants.

A Nationwide Dispersal of New Arrivals

As authorities struggle with huge numbers of U.S.-Mexico border arrivals, and as a growing share of migrants seek humanitarian protection, the federal government has allowed hundreds of thousands of people to enter the United States in recent months pending consideration of their removal or asylum claim in immigration court. Whereas in previous years asylum seekers and other migrants would have found their own way to interior cities where they have family or other social connections, many recent arrivals have headed to some targeted cities. One reason for this movement has been the free buses offered by Texas and Arizona (as well as local jurisdictions and nongovernmental organizations [NGOs]) to cities such as Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. Word of mouth and social media have also allowed migrants to learn of services in potential destinations even before crossing the border.

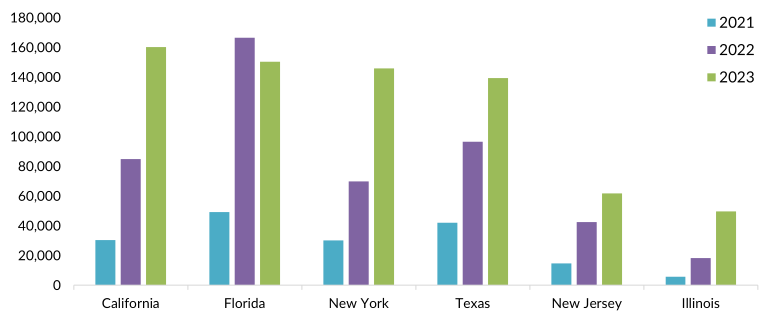

It is impossible to tell precisely how migrants have fanned out nationwide, but data on notices to appear (NTA) in immigration court, which are given to migrants at the border, offer a useful indicator. For the first 11 months of fiscal year (FY) 2023, more than twice as many NTAs were filed in interior states such as New York and Illinois as in FY 2022 (see Figure 1). While the number of NTAs in general has gone up, the rate of increase in these states was much higher than for the nation as a whole. Still, there are limitations to these data: Some NTAs issued in FY 2023 may be for migrants who entered during an earlier year, due to bureaucratic delays or as a result of interior enforcement efforts against long-residing noncitizens; some have missing or inaccurate addresses; and migrants who evade detection at the border never receive an NTA. Those entering through CBP One appointments at ports of entry may not be reflected in these data; 263,000 people had received a CBP One appointment as of August 31, 2023.

Figure 1. Filings for Notices to Appear in Immigration Court, by Select State, FY 2021-23*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 are for the first 11 months of the year.

Note: States represented are those with the highest number of notices to appear (NTAs) in immigration court in FY 2023.

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, “New Proceedings Filed in Immigration Court,” accessed September 17, 2023, available online.

A Patchy Government Safety Net

Box 1. Limits on Work Authorization

The main way that newly arrived migrants can reach self-sufficiency is to work. The federal government has exclusive control over who is eligible to work legally in the United States. Some border arrivals are eligible to receive authorization to work, but not always immediately. Moreover, migrants frequently need assistance with filing their applications.

Below are some general rules for work authorization:

- Asylum applicants can apply for a work permit after their asylum application is filed and has been pending for 150 days. They are eligible to receive work authorization 180 days after filing their asylum application.

- Individuals granted humanitarian parole can apply for work authorization right away.

- Individuals applying for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) can apply concurrently for work authorization.

- Work authorization applications cost $410 for parolees and TPS applicants unless they apply for a fee waiver. The fee is always waived for asylum applicants and is waived for TPS applicants under age 14 or over age 65.

- As of this writing, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is taking a median of three months to process parolees’ work authorization applications and one month for asylum applicants’ initial applications. Work authorization for TPS holders is usually not approved faster than TPS applications themselves, and therefore takes many months.

- Applications for employment authorization and fee waivers can be difficult for migrants to complete without assistance, particularly if they lack strong English skills.

- Just 20 percent of migrants granted parole through a CBP One appointment had filed for work authorization as of this writing.

Only Congress can shorten the 180-day wait for asylum applicants. Mayors, governors, and advocates have pressed the administration to grant work permits more quickly. USCIS has announced its intent to reduce processing times, and some of the recent changes are designed to help shrink the agency’s overall workload, but it is already struggling to speed processing for many types of immigration applications. Other proposals to get new arrivals into the workforce have shaky legal grounds or raise other objections or logistical challenges.

Whether they are able to work legally or not (see Box 1), migrants entering the United States without authorization are largely unable to access the safety-net programs relied upon by many U.S. residents, with limited exceptions. Emergency Medicaid for medical emergencies; free and reduced school lunch; and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) are available regardless of immigration status. But regular Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps), Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for seniors and those with disabilities, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) are unavailable to many noncitizens, particularly those who are not permanent residents.

Asylum applicants, TPS holders, and parolees have slightly greater access to benefits, mainly for children. In 35 states and Washington, DC asylum applicants and TPS holders who are children or pregnant are eligible for federally funded public health insurance (asylum applicants must also have applications pending for more than 180 days, and, if age 14 or older, be authorized to work). In these same states, children and those who are pregnant and have been granted parole that lasts one year or more can access public health insurance. Parolee children can access SNAP, but those who are asylum applicants or TPS holders cannot.

Cubans and Haitians have unique access to public benefits. Parolees, asylum applicants, or individuals in removal proceedings from these countries are eligible for the same benefits granted to resettled refugees, including SNAP, cash, and medical assistance, as well as employment training and placement and other services from resettlement agencies. Those age 65 or older or who have a disability can access SSI for seven years. Language and logistical challenges create barriers to accessing these benefits in some states, but others have facilitated smooth access.

A relatively small number of states provide state-funded benefits to all noncitizens regardless of status or to asylum applicants in particular. For example, California funds public health insurance for residents up to age 26 and over age 49, Illinois provides asylum applicants with food assistance and 24 months of medical coverage, New York State provides public health insurance to all children, and Washington, DC covers health insurance for all residents.

Federal Funding Is No Match for Communities’ Needs

In 2019, Congress for the first time appropriated funds specifically for migrant services, as communities along the Southwest border were strained by an influx of arrivals. Though the funding model has shifted, Congress has continued to appropriate funds for migrant services nearly every year since. At first, the funds were dispersed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) under the Emergency Food and Shelter Program-Humanitarian (EFSP-H). Currently, the model is known as the Shelter and Services Program (SSP), jointly run by FEMA and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). These funds have been instrumental for migrant-serving organizations.

Allocations for SSP, awarded either through reimbursement or in advance, are available to nonprofits and governments that provide services to migrants. Expenditures using SSP funds must fall into specific categories such as transportation, medical services, shelter, and hygiene, but are also available for administrative costs, translation, and infrastructure needs. Each category has specific caps; for instance, transportation can account for just 10 percent of the overall financial award and administrative costs can be no more than 5 percent. SSP funding can only be used for costs related to new arrivals who have been processed by CBP and have an alien registration number (A-number). Under EFSP-H, money could only be used for services within the first 30 days of a migrant’s release from federal custody, but the limit was extended to 45 days in the FY 2023 appropriations negotiations process, a change welcomed by NGOs and localities serving migrants.

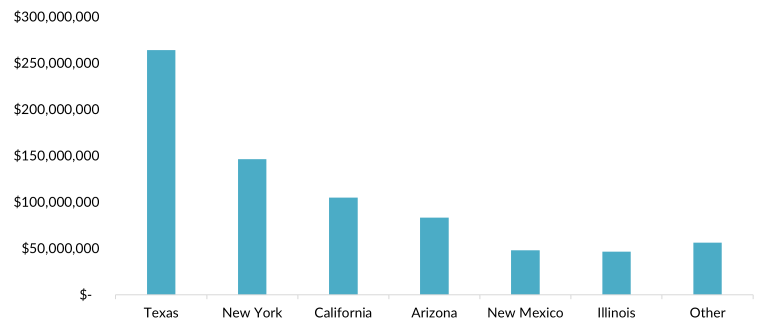

In FY 2023, the total federal funding available to defray migrant services amounted to approximately $800 million: about 55 percent allocated through EFSP-H and the rest through SSP. Recipients in Texas and New York received the most (see Figure 2). The spread in funding, particularly for the interior states, mirrors the top destinations for migrants.

Figure 2. Funding for Shelter and Services Program and Emergency Food and Shelter Program-Humanitarian, by Recipient Location, FY 2023*

* Data for Shelter and Services Program funding are as of September 27.

Note: Data for all funding recipients are not available. Figure shows states of recipients as listed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Sources: FEMA, “Emergency Food and Shelter Program,” updated June 26, 2023, available online; FEMA, “Shelter and Services Program Awards,” updated September 27, 2023, available online.

Still, these funds remain insufficient. The $145 million allocated to the New York City government under SSP is less than one-tenth of what the city has spent on migrants in FY 2023. A similar dynamic is true in other cities.

The federal funding system is also not seamless. Many organizations report delays in reimbursement and cumbersome reporting requirements. This year, SSP moved away from being a competitive grant process to one that is targeted, based on organizations that had previously received grants, CBP data on border crossings, and migrants’ destinations. This shift has raised concerns about the ability of new organizations to apply for funding.

Even still, SSP funding faces an uncertain future. In its FY 2024 budget request, the administration asked for $84 million for SSP funding, a major reduction from the approximately $800 million in FY 2023, though it included SSP as a potential beneficiary of a separate $800 million Southwest Border Contingency Fund. Deadlocked congressional budget negotiations and concerns about conditions at the U.S.-Mexico border threaten these deliberations. Despite the fact that this funding has covered just a fraction of costs, its loss would severely diminish the ability of local governments and organizations to care for new arrivals.

Cities Struggle to Fill the Gap

Given the insufficient federal funding and newcomers’ limited access to public benefits, city services have become the last resort for meeting individuals’ basic needs. Local leaders have responded in different ways and with patchwork approaches, relying heavily on local nonprofits for assistance. Most have focused their funding on immediate needs such as help with food, shelter, and onward travel.

Housing has been a major problem. Homeless shelters and hotels have been common solutions to meet this need, and some cities have even used shared housing arrangements in airports, school gyms, and police stations. Yet challenges persist, and cities are operating at different scales. New York City has absorbed the largest number of migrants this year, and close to 60,000 were living in its shelter system in September. The city is unique in that, due to a series of legal settlements from the late 1970s and early 1980s, it is obligated to provide shelter to anyone who seeks it. With traditional shelters filling up, New York has established 200 other locations to place migrants, including more than 140 hotels, school gyms, churches and other religious institutions, previously vacant buildings, and large tents. It continues to search for additional venues. The city comptroller and others have raised concerns about a no-bid contract the city signed for these migrant housing services, amid questions about the costs and quality of services provided by some contractors. The city comptroller has considered revoking the mayor’s authority to fast-track contracts related to migrant services, to give them more scrutiny.

As of late September, Chicago was housing nearly 9,000 migrants in 19 city facilities, plus approximately 2,000 in airports and police stations pending placement in established shelters. The city plans to build winterized tents as an alternative.

Migrants arriving in Washington, DC can find short-term shelter in neighboring Montgomery County, Maryland (for two nights) or in the District (for seven nights). In addition, the DC government has been funding hotel stays for more than 1,000 migrants and contracting with local restaurants to provide meals. These facilities have not met demand, however, leaving new arrivals to crash with volunteers or sleep in cars. However, the District of Columbia has an advantage over New York City in that fewer than one-quarter of arriving migrants intend to stay in the area, according to the District’s Department of Human Services, while the rest plan to travel to other places—including New York.

Denver, which has seen high arrivals on and off since last December, was likewise sheltering about 1,000 migrants in early September in migrant-specific shelters. During past periods of sizeable arrivals, in December and January, the city opened emergency overnight shelters in recreation centers and other locations. The city has also requested that faith-based organizations provide overnight shelter for migrants leaving town the next day. At one point this spring, hundreds of migrants camped in a university parking garage, supported by the campus and local migrant-serving organizations.

A New Twist on Old Housing Challenges

In many cities, the struggle to house migrants has exacerbated a pre-existing housing crisis. The wind-down of federal COVID-19 relief funds exacerbated the crisis, as individuals lost supplemental income and cities ended some of their mortgage- and rent-support programs. Many cities’ migrant shelters are separate from those for local homeless populations, which allows officials both to meet migrants’ specific (and often broader) needs and avoids competition between the groups. A new Washington, DC law establishing its Office of Migrant Affairs explicitly excluded migrants from the city’s regular services for unhoused residents.

Given the housing challenges, many cities are left with little ability to offer migrants longer-term integration assistance, including employment services, legal aid, and mental health and health care. Nonprofit service providers can sometimes fill these gaps, but their capacity is hardly sufficient.

Cities do not yet seem to have strategies for helping migrants exit shelters and become self-supporting. In July, New York City began giving some single adult migrants 60 days’ notice to find their own housing, starting with those who had been in shelters longer, and ramping up casework assistance to help arrivals find other options. Migrants unable to find other housing can re-enroll in shelters but will be granted just 30 additional days. Because of its right to shelter, New York City currently has no way to force migrants to find other housing. In May, the New York State Legislature approved a $25 million Migrant Relocation Assistance Program aimed at relocating migrants to other communities in the state, offering them a year of rental assistance, case management, and other services. As of late August, no families had relocated through the program, although more than 100 had begun the process. Illinois is funding up to six months of rental assistance for migrants who have passed through publicly funded shelters or hotel stays in the state; as of July, more than 1,000 migrants had been approved for the program. But the expensive rental market in major U.S. cities can be a strong barrier to exiting government-run shelters.

A recent collaboration between the federal government and New York State and City allows the housing of up to 2,500 migrants in Brooklyn’s Floyd Bennett Field, a national parkland owned by the Interior Department. The federal government is also planning to send 50 federal employees to assist migrants who wish to apply for asylum and work authorization. As of this writing, the facility was not open; it has been challenged in court by some state and local lawmakers. Other jurisdictions are also dedicating resources to helping migrants apply for work authorization. New York Governor Kathy Hochul has dedicated 250 National Guard members and $50 million to case management in such efforts. Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey said in early September that her state would partner with local refugee resettlement offices to help migrants apply for work authorization, and would pay application fees.

Adapting to the New Reality

It is unlikely that arrivals to U.S. cities far from the southwest border will abate, especially given rising arrivals in August and September. Despite long timelines for adjudicating asylum claims and delays in issuing work authorization, migrants eventually integrate into communities and become self-sufficient. But the adjustment period can be difficult, particularly for those who lack family and social networks. In the meantime, cities are estimating tremendous costs to fill this gap and meet migrants’ basic needs for food and shelter.

The Biden administration’s recent move to speed up processing of work permits for some newcomers is likely to help people support themselves more quickly. So will the expansion of TPS, assuming the government is able to shorten processing times. There are plenty of other ideas for reducing the burden on cities and states, but many are unlikely to happen in the short run. Congress appears unwilling or unable to enact broader reforms that could reduce pressure at the border or hasten asylum applicants’ access to work authorization. Increased and more flexible federal funding for localities is similarly likely stymied by widespread political squabbling.

Advocates and a number of Democratic political leaders have asked the Biden administration to establish a more coordinated resettlement plan for arriving migrants, which could include connecting those arriving without strong U.S. ties to cities with high labor demand and lower housing costs. They have also pushed for further coordination among local and state governments, philanthropic groups, and nongovernment organizations to share best practices for efficiently meeting migrants' immediate needs and supporting more sustained systems for the long run.

Another option exists in the federal government’s new use of community sponsorship parole. In an effort to reduce irregular crossings and perhaps limit the burden on U.S. cities, the administration’s parole programs for Ukrainians and for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans require new arrivals to have a sponsor in the United States. Sponsors must take responsibility for receiving and financially supporting parolees for the duration of their parole. This assistance may include ensuring housing, access to medical care, enrolling children in school, or accessing language classes. It is unclear whether most sponsors are adequately meeting those obligations, so the true potential is so far unknown. But some version of this model could hold promise for better distributing the costs of supporting new migrants—whether they be parolees, asylum seekers, or others—and draw on the generosity of U.S. communities seeking to help migrants in need.

Whatever the solution, it is clear that cities require tools and resources to both meet migrants’ immediate needs and assist their long-term integration. With limited federal support, local communities have found themselves on the front lines and are buckling under the weight.

The authors thank Kathleen Bush-Joseph for her research assistance.

Sources

Ainsley, Julia. 2023. Concern Rises in the Biden Administration that New York Is Fumbling Its Migrant Problem, U.S. Officials Say. NBC News, September 12, 2023. Available online.

Beaty, Kevin and Rebecca Tauber. 2023. More People Are Crossing the U.S. Border and Are Likely Headed to Denver. Is the City Prepared to Serve New Migrant Arrivals? Denverite, September 8, 2023. Available online.

Brice-Saddler, Michael. 2023. As Migrants Continue to Arrive in D.C. Concerns Remain about Capacity. The Washington Post, September 14, 2023. Available online.

Broder, Tanya and Gabrielle Lessard. 2023. Overview of Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs. Los Angeles: National Immigration Law Center (NILC). Available online.

City of New York. 2023. As Asylum Seekers in City's Care Tops 54,800, Mayor Adams Announces New Policy to Help Asylum Seekers Move from Shelter. Press release, July 19, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Mayor Adams Announces New York Has Cared for More than 100,000 Asylum Seekers Since Last Spring. Press release, August 16, 2023. Available online.

Fandos, Nicholas. N.Y. Lawmakers Sue to Block Migrants from Floyd Bennett Field. The New York Times, September 19, 2023. Available online.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). 2023. Emergency Food and Shelter Program. Updated June 26, 2023. Available online.

---. 2023. Shelter and Services Program Awards. Updated September 27, 2023. Available online.

Giambrone, Andrew. 2023. Despite State Emergency, New York Has Resettled Zero Migrant Families Through Flagship Program. New York Focus, August 29, 2023. Available online.

Gomez, Amanda Michelle. 2022. D.C. Council Votes to Create Office to Support Migrants, but Excludes Them from Other Homeless Services. DCist, September 21, 2022. Available online.

Hernandez, Esteban L. 2023. Denver Sees Another Uptick in Migrant Arrivals. Axios, April 23, 2023. Available online.

Hogan, Gwynn. 2023. City Hall About to Put Migrants in Shelters on Shorter Clockers. The City, September 19, 2023. Available online.

Kane, Lizzie and Laura Rodríguez Presa. 2023. Migrants Are Leaving Chicago Shelters with the Help of Rental Assistance. Some Landlords Are Skeptical, Others Step In to Help. The Chicago Tribune, July 21, 2023. Available online.

Kelty, Bennito L. 2023. Migrants Awaiting Processing Turn Auraria Campus Garage into Makeshift Shelter. Westword, May 10, 2023. Available online.

Lorio, Michael and Emmanuel Camarillo. 2023. Far South Side Residents Divided on Migrant Camp Landing on Their Turf. The Chicago Sun-Times, September 13, 2023. Available online.

Meko, Hurubie. 2023. What to Know About the Migrant Crisis in New York. The New York Times, September 14, 2023. Available online.

National Immigration Law Center (NILC). 2023. Table: Medical Assistance Programs for Immigrants in Various States. Fact sheet, NILC, Washington, DC, August 2023. Available online.

New York City Council. 2023. Statements from Speaker Adams and New York Immigration Coalition on Biden Administration’s Extension and Re-Designation of Venezuela for Temporary Protected Status. Press release, September 21, 2023. Available online.

New York State. 2023. Governor Hochul Deploys 150 Additional National Guard Personnel to Support Response to Asylum Seeker Crisis. Press release, September 25, 2023. Available online.

Office of the Texas Governor Greg Abbott. 2023. Operation Lone Star Expands Successful Migrant Busing Strategy. Press release, June 16, 2023. Available online.

Olivo, Antonio. 2023. D.C. Opens Migrant Center as It Braces for More Border Buses. The Washington Post, June 2, 2023. Available online.

Owens, Caitlin, Stef W. Kight, Monica Eng, and Alayna Alvarez. 2023. Migrant Surge Makes US Housing Crisis Worse. Axios. September 23, 2023. Available online.

Pitzl, Mary Jo. 2023. Arizona Will Keep Sending Migrants Where ‘They Actually Need to Go’ Says Democratic Governor Katie Hobbs. USA Today, January 21, 2023. Available online.

Schulte, Sarah. 2023. Chicago's Newest Migrant Shelter Opens in Greektown; 200 Single Men Capacity. WLS-TV, September 15, 2023. Available online.

Spinelli, Courtney. 2023. Record Number of Migrant Buses Arrive in Chicago in Single Weekend; City Discusses Its Response. WGN News, September 25, 2023. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2023. Top County Destinations for Asylum Seekers. June 21, 2023. Available online.

---. N.d. New Proceedings Filed in Immigration Court. Accessed September 15, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). N.d. Online Request to Be a Supporter and Declaration of Financial Support. Accessed September 14, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). 2022. ACF’s Office of Refugee Resettlement Benefits for Cuban and Haitian Entrants. Fact sheet, ORR, Washington, DC, December 2022. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2023. Fact Sheet: The Biden-Harris Administration Takes New Actions to Increase Border Enforcement and Accelerate Processing for Work Authorizations, while Continuing to Call on Congress to Act. Press release, September 20, 2023. Available online.

Van Buskirk, Chris. 2023. Gov. Healy Expands Legal Services for Migrants Living in Emergency Shelters. The Boston Herald. September 21, 2023. Available online.

WABC-TV Eyewitness News. 2023. Floyd Bennett Field to Be Used to House Asylum Seekers in Brooklyn, Hochul Announces. WABC-TV, August 21, 2023. Available online.

Webster, Elizabeth. 2023. FEMA’s Emergency Food and Shelter Program -Humanitarian Relief (EFSP-H) and the New Shelter and Services Program (SSP). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

---. 2023. Shelter and Services (SSP) FY2023 Funding. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Webster, Elizabeth and Audrey Singer. 2023. FEMA Assistance for Migrants Through the Emergency Food and Shelter Program Humanitarian (EFSP-H) and Shelter and Services Program (SSP). Washington DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.